In the fast-paced digital landscape, viral media events capture global attention. From natural disasters and geopolitical shifts to groundbreaking tech releases and cultural phenomena, these moments dominate headlines and online conversations. But as the world's eyes turn towards these events, a different group also takes notice: malicious actors looking to capitalize on the public's interest and urgency.

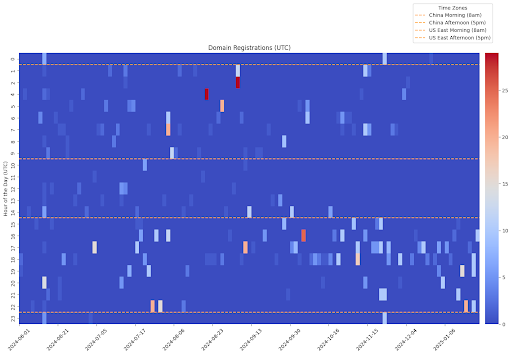

Our security research team recently undertook a project to identify and analyze scam and malicious domains and websites that emerge in the wake of high-profile viral media events. Leveraging AI-driven research capabilities, we aimed to understand how threat actors exploit these moments for financial gain and other nefarious purposes.

AI-Powered Approach to Identify Viral Media Events

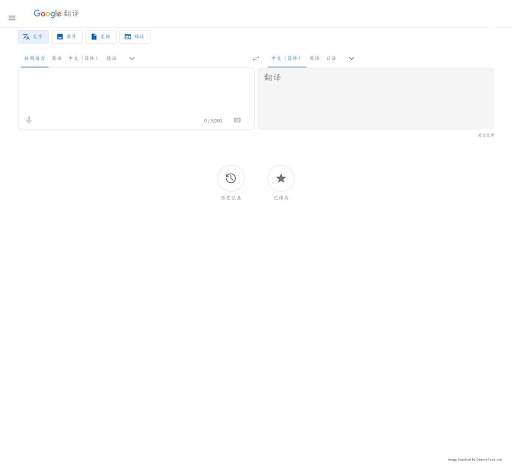

Our research methodology involved using AI to first identify viral media events that occurred between January 1, 2025, and the present. The AI research capability was prompted to pinpoint the approximate start, peak, and end of each event's virality across mass media and wide coverage.

For each identified event, we then tasked the AI with generating a list of keywords likely to appear in domain names or website titles seeking to associate with the event. The prompt for keyword generation was specifically designed to identify terms that scammers might use to create deceptive sites.

We sampled multiple event topics from the AI's output for deeper analysis, including the Los Angeles Fire, "NoKings," DeepSeek / China AI developments, the ongoing Trade War, and the Ukraine/Russia conflict.

An example of the AI's output for a significant tech event is as follows:

By searching for these keywords or similar terms in domain registrations and website titles within the estimated first and last observed timeframes, we detected several domains that appeared to be malicious. It was anticipated that most scam-related or malicious domains would emerge around the peak of viral activity and potentially persist until the latest observed dates.

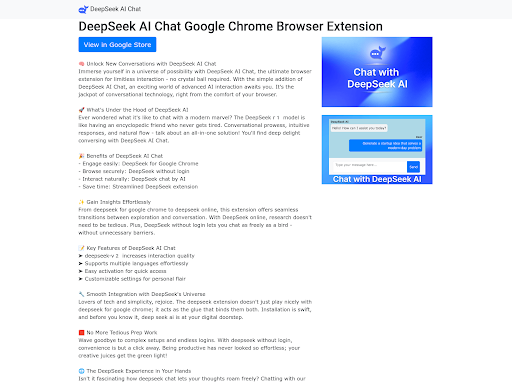

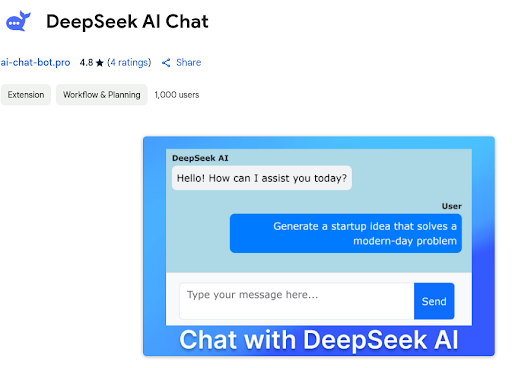

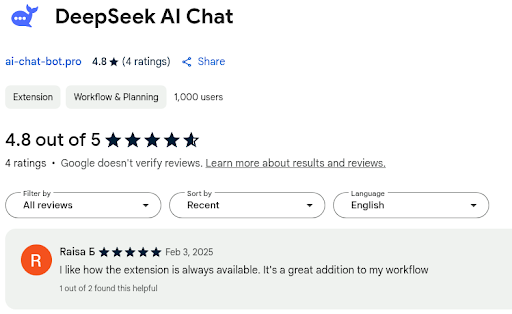

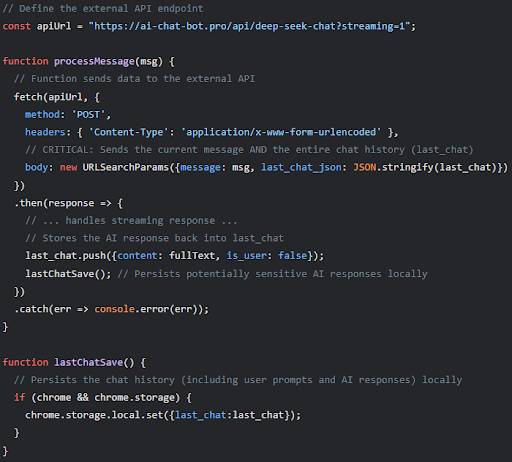

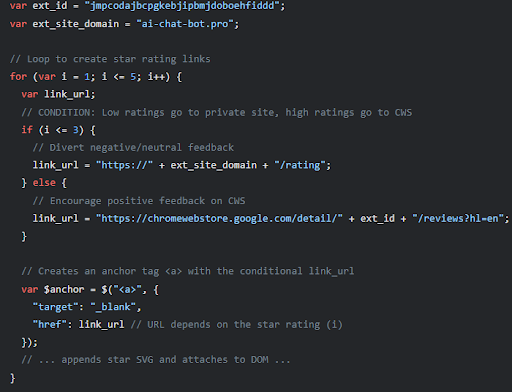

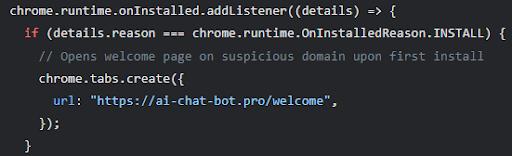

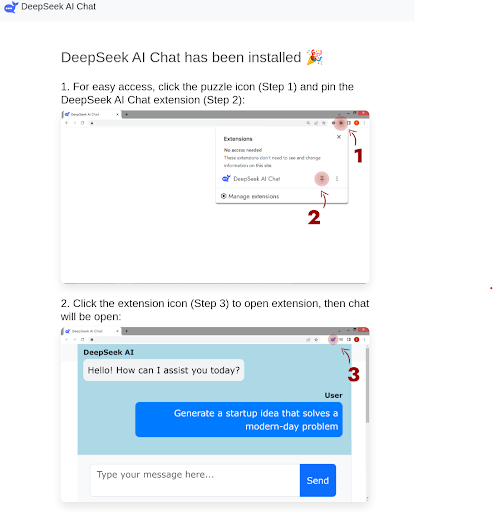

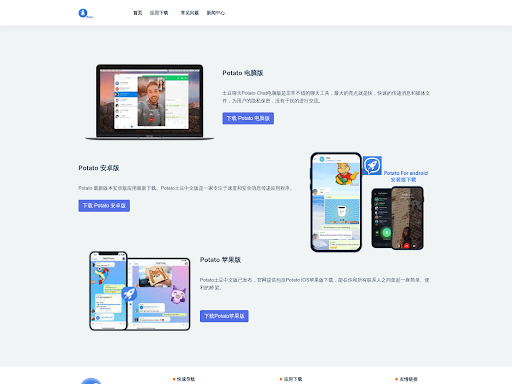

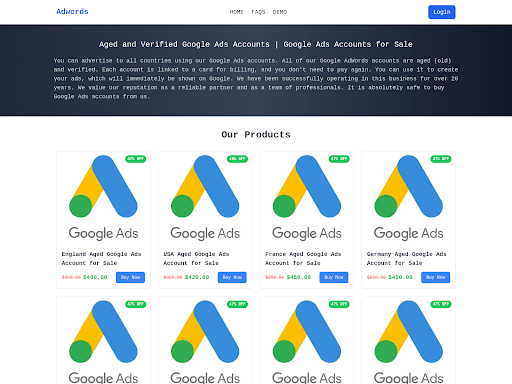

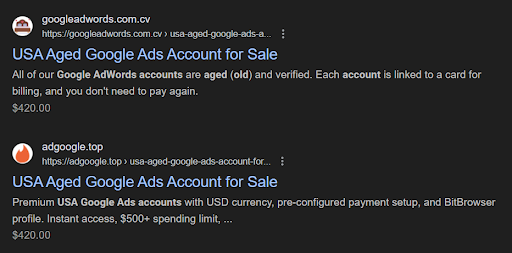

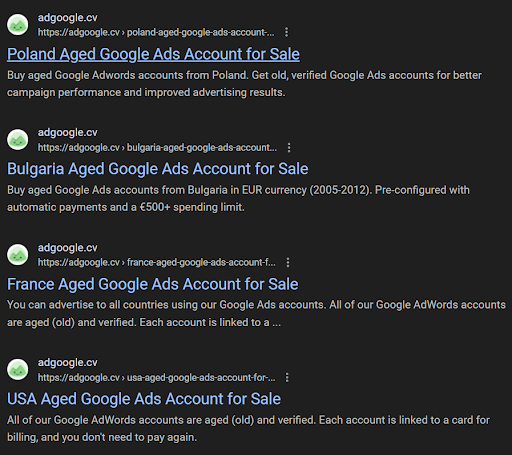

A sampling of the malicious findings from the AI-generated keywords for the “Deepseek AI Release & Market Impact” event are shown below.

Multiple scams were identified. Perhaps the most financially successful ones relating to the DeepSeek event were fake cryptocurrency meme coins created to capitalize on a growing trend of novice investors looking for the next hyped up moonshot meme coin. In the case of DeepSeek, according to BeInCrypto (cited in the table above), fake meme coins accrued over 46 million dollars worth before the rug was pulled, presumably indicating the scammers had cashed out.

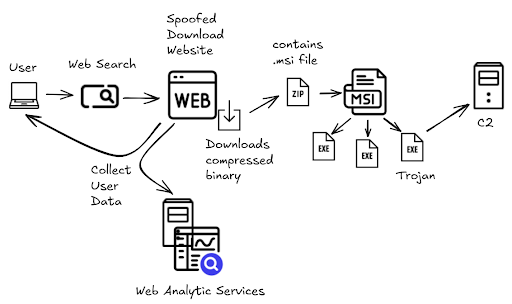

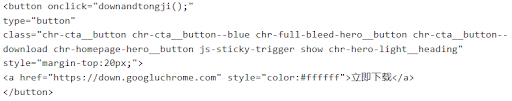

Additionally, multiple malware delivery websites were observed primarily delivering Windows trojans and malicious browser extensions. One extension in particular was observed with capabilities to legitimately use DeepSeek API for working functionality, but also connected to a remote domain to retrieve and execute arbitrary JavaScript files likely for the purpose of credential harvesting or session hijacking.

Expected vs. Actual Findings Regarding Viral Events

Based on the nature of viral events, we anticipated finding websites and domains attempting to:

- Amplify or create spin-off movements to gain attention.

- Sell merchandise related to the event.

- Collect user information (contact details, experiences, etc.) for spam, resale, or phishing.

- Push deceptive or derisive narratives to further enthral individuals in alleged movements, leading to potential merchandise sales, information gathering, or fraudulent donations.

- Act as "ambulance chasers," with alleged law firms soliciting victims of tragedies for potential profit.

- Delivery of malware, adware, or spyware through deceptive downloads.

While we did observe instances of these expected tactics, our research consistently revealed a predominant motivation across the sampled events: direct financial profit.

For almost all events sampled, we identified websites explicitly seeking to profit by:

- Allegedly to be part of a legitimate donation foundation supporting the cause (e.g., for the LA Fire, the Ukraine/Russia conflict, and other tragedies like the Myanmar earthquakes).

- Selling merchandise related to the event topic.

- Creating and promoting meme cryptocurrency coins based on the event.

Beyond direct financial scams, we also confirmed the presence of websites designed for:

- Malware delivery.

- Information collection schemes.

- Disinformation campaigns aimed at pushing deceptive and derisive narratives.

Emerging Patterns and Linked Actors Across Viral Events

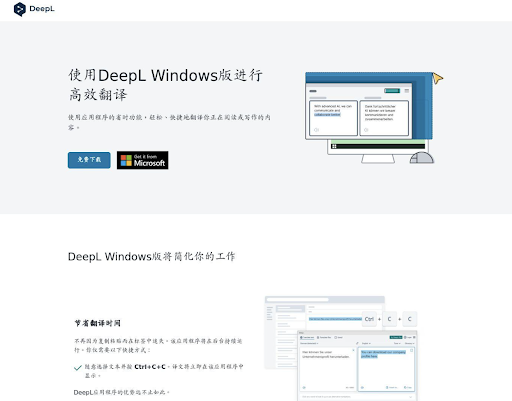

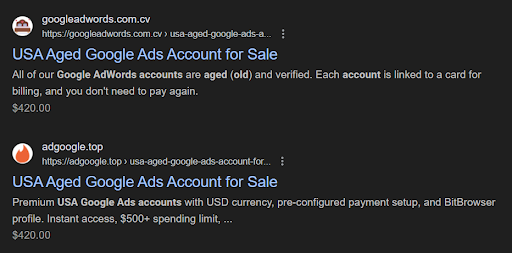

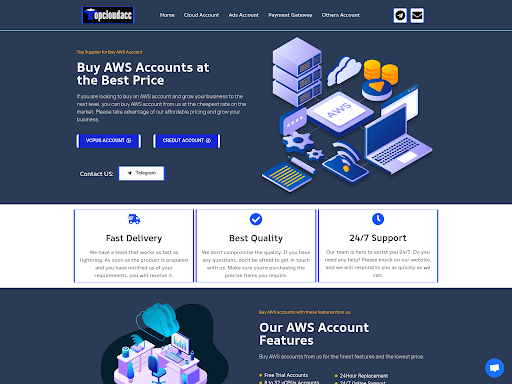

A significant observation was the emergence of common elements across multiple relatively unique-looking websites covering different viral events. This suggests the likelihood of the same actor or group being behind these diverse scams.

One example was websites that appeared to create meme cryptocurrency coins in response to several highly publicized events in the recent US political landscape and natural disasters, including US tariffs, the trade war, and the LA fire. Several sites appeared to share design, language, or infrastructure elements across these seemingly distinct scam sites points towards a connected operation.

One suspected cluster focused on scamming meme coins commonly utilized IP ISP: Vercel Inc, Registrar: Namecheap, SSL Issuer CN: R10 or R11, and commonly had website titles with a meme coin name in all caps such as LAFIRE, $LAFIRE, GROK and TOOT. Pivots from this pattern identified several other suspected scam meme coin websites including $TittsFart, $TUCHI, $TOOT, $GWOK, and $SUNG, which is a meme of the top Anime show Solo Leveling’s main character Sung Jinwoo.

The most prevalent scams observed were those pushing newly created cryptocurrency meme coins, which attracted novice traders seeking to ride the hype of the viral event to make easy money. Once the meme coin reaches a certain threshold of time or sale price, the scammers would cash out selling all of their coins and the meme coin would subsequently collapse. These meme coin scams were observed in a wide range of events including international conflicts such as the Russian attacks on Ukraine, the US Trade War, the LA Fire, and the Myanmar Earthquake.

The following are example findings of similar websites, each associated with inactive social media accounts that claim to sell cryptocurrency coins linked to widely publicized media events.

tradewar[.]space, tradewar[.]lol, tradewar[.]site attempt to persuade others to purchase Trade War themed cryptocurrency coins.

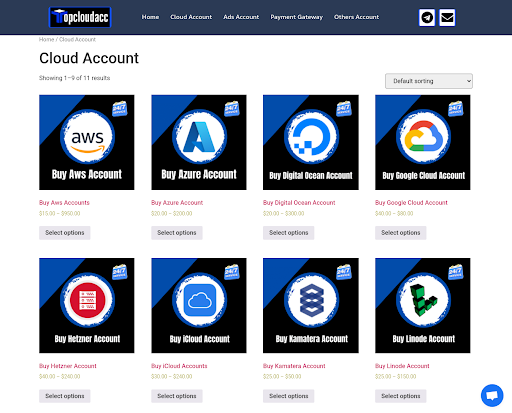

lafirebrigade.co[.]uk and lafireonsol[.]xyz attempt to persuade others to purchase a LA Fire-themed cryptocurrency coin.

![lafirebrigade.co[.]uk, lafireonsol[.]xyz attempt to persuade others to purchase a LA Fire themed cryptocurrency coin](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/6941445776ba1afe6af83186/695263adcee67731ab0f4b98_AD_4nXcW1mcqkE3HlkIVrjj_H5Ld5Ta0zChrygeWpSwauXAt3reS5WxgVSOHbLQN5HusW4Verqd8Fh-keX9vuoM_5TGWDPgF_FDCtKvu70h36AwocpeU-jOgWwuyyNvgZlKUue8AJ4iJ8A.png)

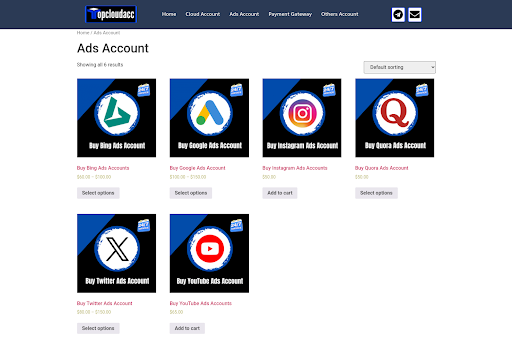

lafire[.]io is another website attempting to pawn off scam crypto coin LAFIRE as a donation fund tactic.

![lafire[.]io is another website attempting to pawn off scam crypto coin LAFIRE as a donation fund tactic.](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/6941445776ba1afe6af83186/695263adcee67731ab0f4b95_AD_4nXeTPwO0WvgKdnPjmL3T0e9TVMWo_uSJ_zTkRIAvt96XjOJlNAdLjpxCSaCaIoXhKQ6yYUrkxz1sshbhPWrN4KK3iJqIz2kK6NaRPD281mRG4HlrHxZZp6P1EB45aTC9BI4Pk3xy2Q.png)

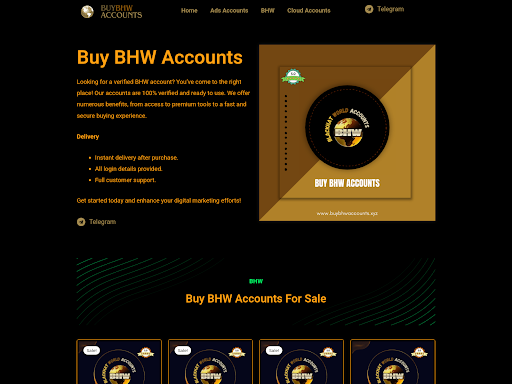

Myanmar Meme coin myanmarmeme[.]top

![Myanmar Meme coin myanmarmeme[.]top](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/6941445776ba1afe6af83186/695263adcee67731ab0f4b88_AD_4nXdL0VvE3fe3lV1aqfTBVWCX0npkinxZaM93ilorsB2LZgzAo9ToEYLw6P4-sFmQJkevRYtiA_x3v-FGskdxMHw-YseSqB8e2GWJYDtf7xFKv-drkwDSxGSdZsfsGDoX0T8b9NsvnA.png)

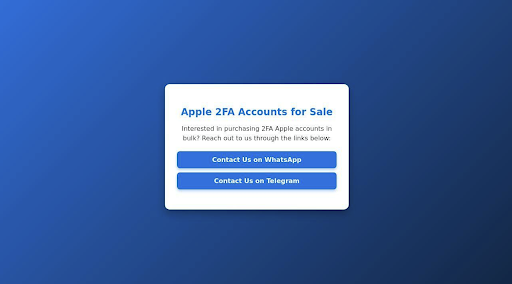

tootonsol[.]xyz

![tootonsol[.]xyz](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/6941445776ba1afe6af83186/695263adcee67731ab0f4b7c_AD_4nXfaLyaUv6_eQKUtLyaEfbqgZ31ZwiftmI0Y8pNCwbytzn5fWk0CrPIEIyU1_fMvX4htgvM1-Jz6yHWy_bm-rBbFNXdj2D5kPxCCh2p-CRWgJI1yt9XSbXQJArtnnfrVQ3COCJm88A.png)

gork[.]ink suspected scam meme coin attempted to capitalize on the recent news hype of the Elon Musk-owned xAI Grok AI model. Decrypt reported the alleged scam meme coin achieved $160 million in market capitalization before crashing.

![gork[.]ink suspected scam meme coin attempted to capitalize on the recent news hype of Elon Musk owned xAI Grok AI model](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/6941445776ba1afe6af83186/695263adcee67731ab0f4b8e_AD_4nXd8obIUxOaX5UXJx98HBhqo6FA3Sju-qaL6zle5_MnOTf0J1Tw9q4VhBCvTFbDEZUDdI3dN7GUU2-nl0W-AgqafyIw14_OBYIlNNKL-9avwkX0RU3MwV0IXXVJNyPmeX5xALlYXKg.png)

The second most prevalent scam tactic observed involved fake donations, sometimes masquerading as established entities such as the American Red Cross, World Food Program or LA Fire departments.

Specifically relating to the LA fire event, BforeAI published a report highlighting a similar method of identifying these types of scam domains in which a variety of websites were identified. Their report also noted multiple consistencies in the types of domains and websites being created in the aftermath of natural disasters.

lafirevictimsupport[.]com and lafireonsol[.]xyz purported to collect donations on behalf of the American Red Cross.

![lafirevictimsupport[.]com, lafireonsol[.]xyz purported to collect donations on behalf of the American Red Cross](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/6941445776ba1afe6af83186/695263adcee67731ab0f4b82_AD_4nXdVvQbUD_x8SGl5a5vyY4-73xb1Ul1wuwQKfc33rDMHab3VS0DYP7HyC9aq2hZWHRA7jJPLIVuFVdBaubzIAbHbJVe-tZ78gi_tPJf0ma_5v8ogBQUXrlhRDg1JzC6yb4JZWZnBMg.png)

donorsee-charitable[.]com cryptocurrency donation scheme for Myanmar earthquake victims purporting to be part of the World Food Program (WFPUSA).

Malicious Actors Leveraging Viral Media Events for Financial Gain

Our research highlights the clear and present danger posed by malicious actors who quickly leverage viral media events for their own gain. The speed at which these events unfold provides a fertile ground for scammers to deploy a variety of schemes primarily focused on financial exploitation through fake donations, merchandise sales, and cryptocurrency scams. The observed connections between scam sites operating across different viral topics underscore the adaptive and potentially organized nature of these threat actors.

Staying vigilant and critically evaluating any website or domain seeking engagement related to a viral event is crucial. Always verify the legitimacy of organizations, especially those requesting donations or personal information, and be wary of unsolicited offers or urgent calls to action tied to breaking news. As security researchers, we will continue to monitor this evolving threat landscape and share our findings to help the public stay safe online.

Sign Up For DomainTools Investigations’ Newsletter for the Latest Research

Want more from DomainTools Investigations? Be sure to sign up for our monthly newsletter to get the latest research from the team – available on LinkedIn or email.