Analysis of the Doppelgänger / RRN disinformation ecosystem. Learn how this DevOps-style infrastructure uses automated media impersonation, TLD rotation, and cloud-native hosting to target global audiences and evade enforcement.

Executive Summary

The Doppelgänger / RRN ecosystem (RRN = Reliable Recent News) constitutes a new iteration of the Social Design Agency (SDA), a structurally mature, infrastructure-centric disinformation architecture that has been operating continuously from 2022 through 2026. Rather than functioning as a loose collection of spoofed websites or transient propaganda outlets, the network exhibits the hallmarks of a coordinated, professionally managed influence apparatus. Its design prioritizes infrastructure resilience, scalability, and operational continuity over short-term visibility.

At its core, the ecosystem relies on systematic media brand impersonation executed at scale. Recognizable Western news outlets are replicated through domain substitution, typo variants, and semantic extensions, producing a high-volume impersonation layer that mimics legitimate journalism. These impersonation domains are not isolated artifacts; they are anchored to a centralized narrative constellation built around the RRN brand family, which functions as a clearinghouse and coordination node for messaging.

rrn[.]com[.]tr current iteration of Researchers & Reporters Network (aka Doppelganger Disinfo Network)

Domain acquisition patterns indicate batch provisioning during defined campaign waves, most notably in mid-2022 and again in late-2024. These bursts reflect deliberate staging cycles rather than organic domain accumulation. Complementing this provisioning model is a deliberate top-level domain diversification strategy. The operation leverages low-cost and low-scrutiny TLDs, rotates extensions in response to enforcement actions, and preserves second-level domains across TLD swaps to maintain continuity. This enforcement-aware migration pattern demonstrates pre-positioned redundancy and lifecycle planning.

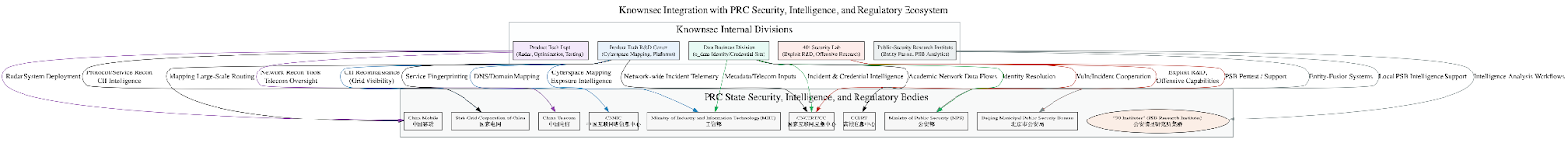

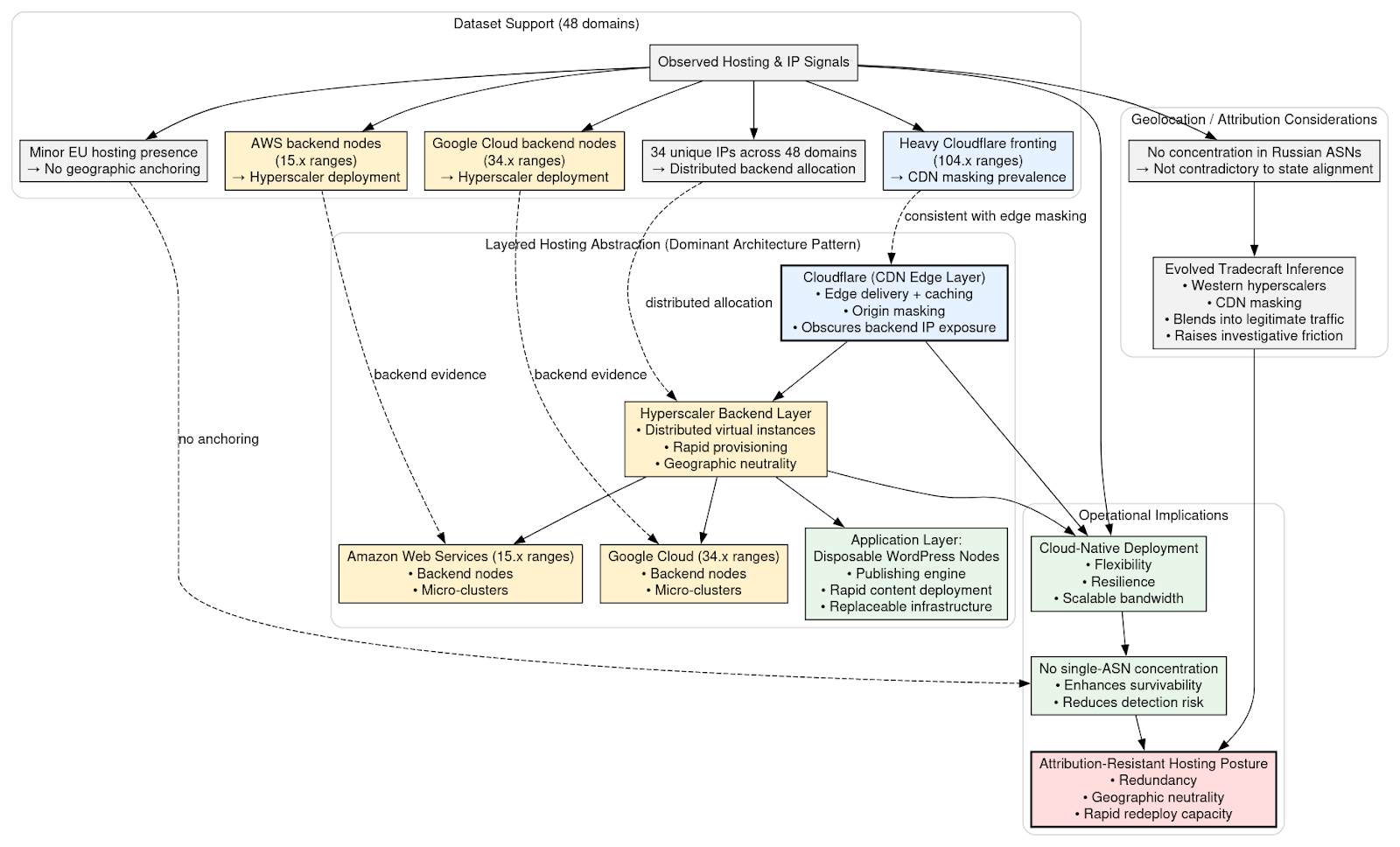

Hosting and delivery architecture further reinforce the operation’s sophistication. The ecosystem is cloud-native and heavily fronted by content delivery networks that obscure origin infrastructure. Backend services are distributed across hyperscaler platforms, including Google Cloud and to a lesser extent AWS, along with static asset reuse from legitimate domains, with micro-clustering patterns that distribute risk and reduce single points of failure. The absence of concentrated Russian hosting infrastructure suggests attribution resistance through geographic neutrality rather than lack of coordination.

Backend artifacts reveal structured CMS management. WordPress deployments exhibit role-based segmentation, coordinated account provisioning, and SEO-oriented publishing controls. These features indicate centralized backend governance and editorial workflow discipline. The infrastructure also reflects automated domain variant generation, employing scripted logic for brand tokens, typographical alterations, and semantic suffix combinations. This level of automation is consistent with a provisioning pipeline rather than manual spoofing. Assistance from Amazon Web Services Threat Intelligence enriched the presence of AWS IP addresses, identifying primarily legitimate assets being reused in off-AWS infrastructure.

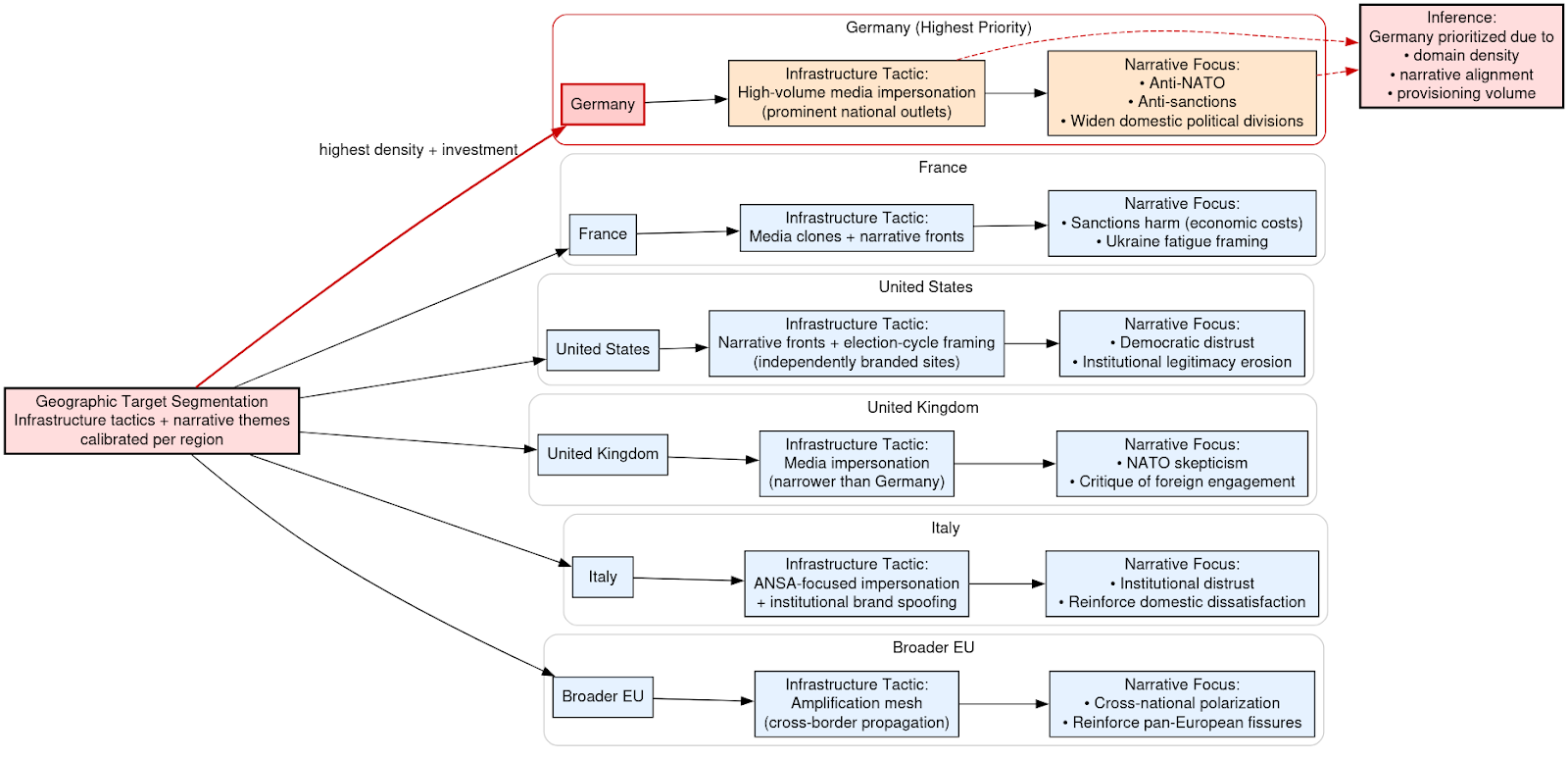

The campaign demonstrates deliberate geographic micro-targeting across European Union member states and the United States. Infrastructure segmentation mirrors narrative segmentation, with country-specific impersonation clusters aligned to regional political contexts. This coupling of technical segmentation and messaging strategy underscores a hybridization of cyber infrastructure tradecraft and psychological operations.

Taken together, these characteristics indicate DevOps-style provisioning discipline and resilience engineering. Domains are stockpiled, rotated, and redeployed with minimal disruption. Infrastructure is compartmentalized, diversified, and rapidly replaceable. Such operational maturity is consistent with institutional backing and sustained management, rather than opportunistic or freelance activity.

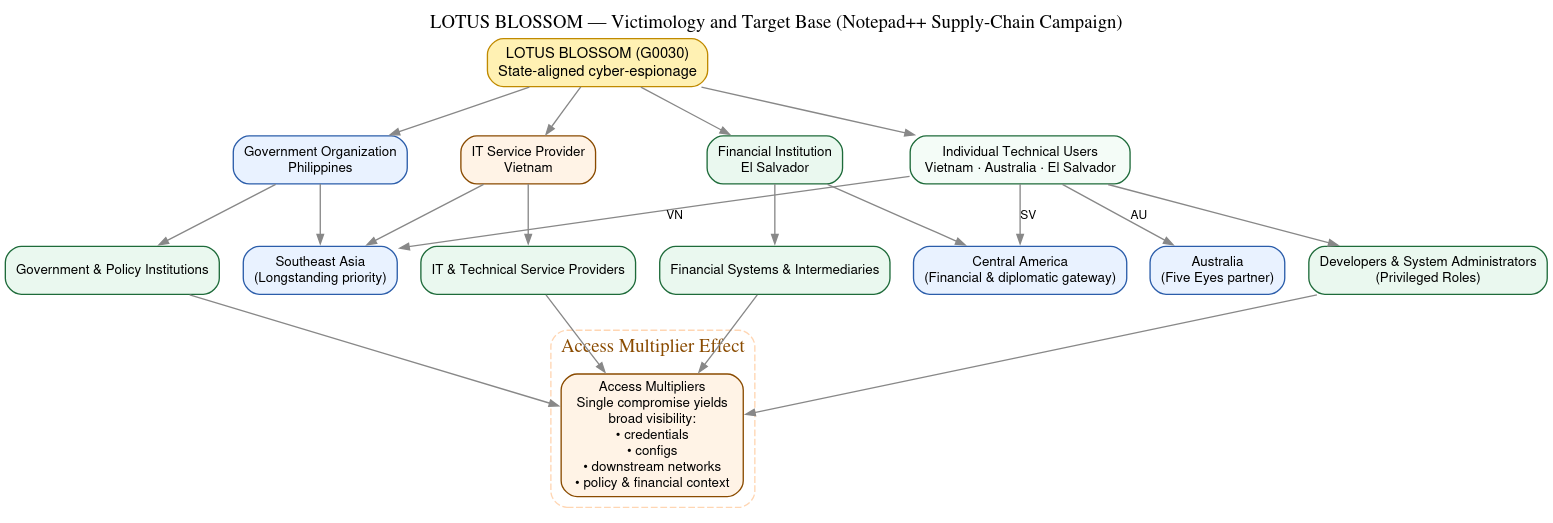

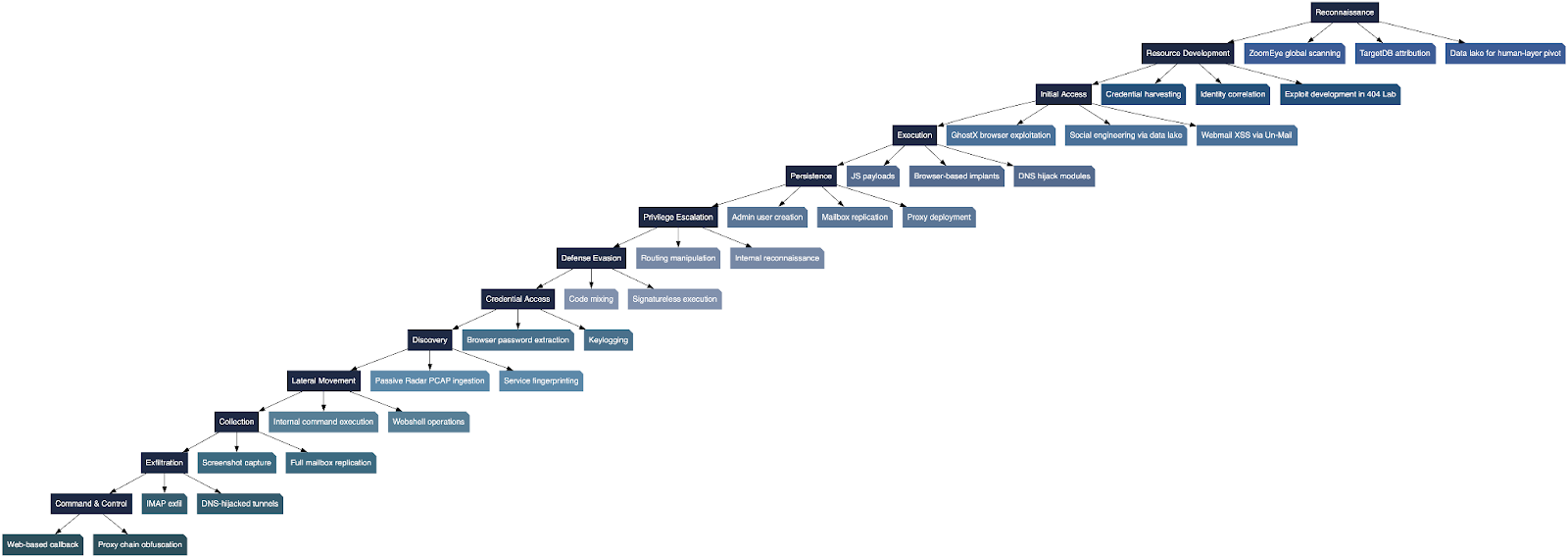

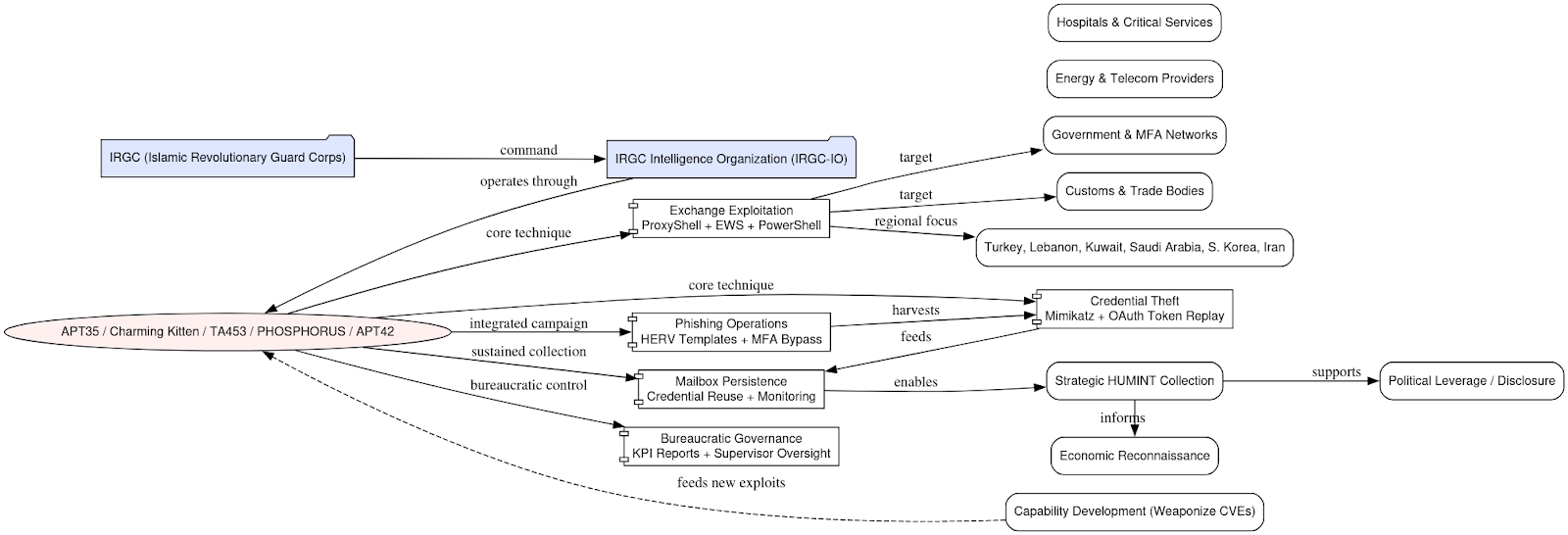

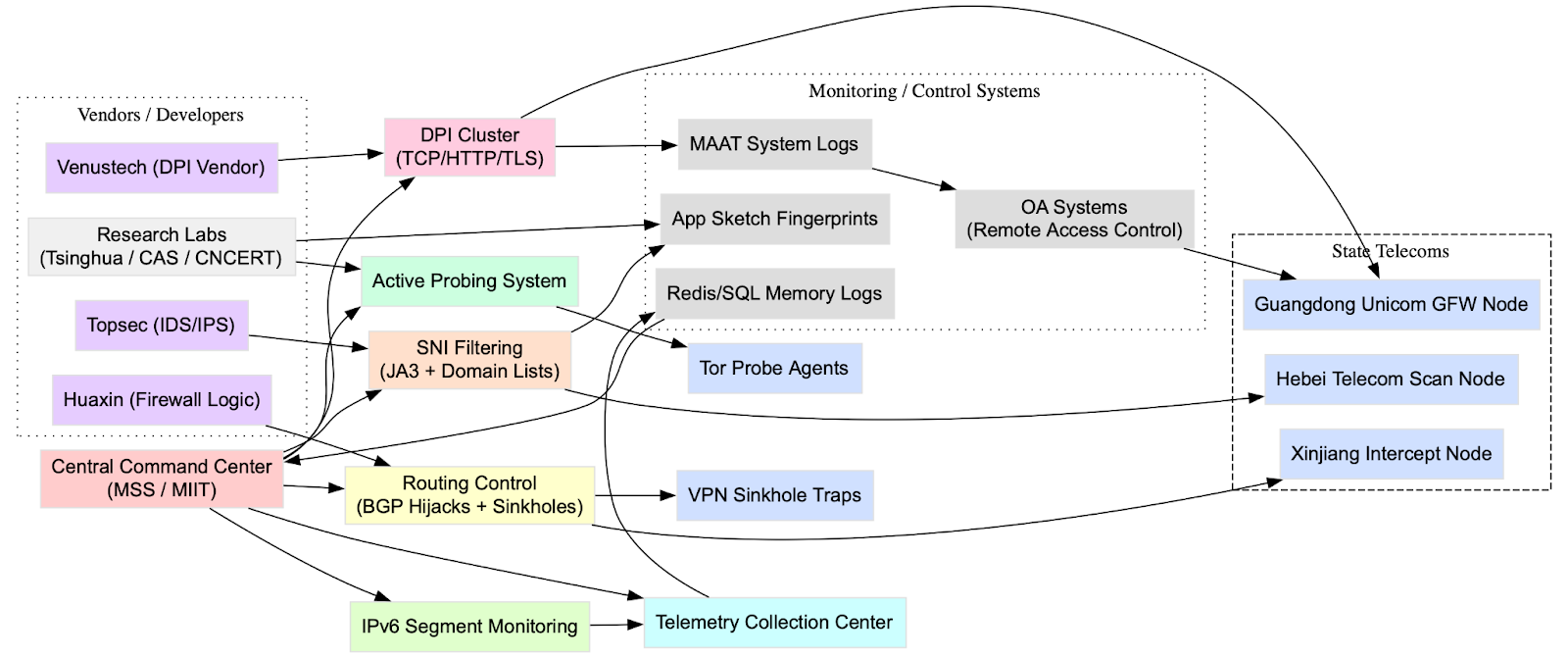

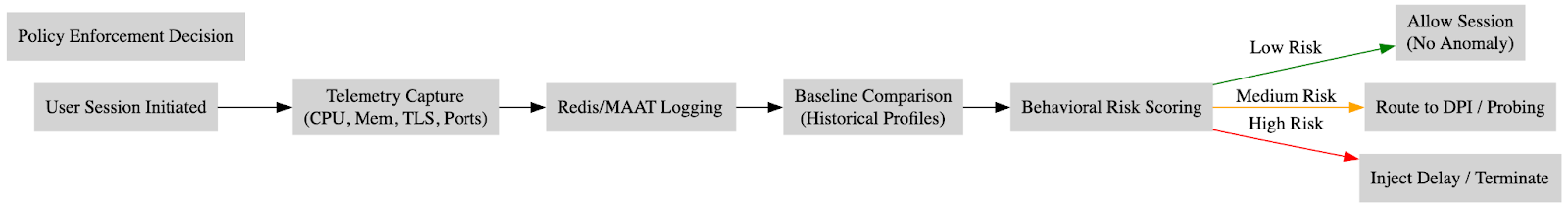

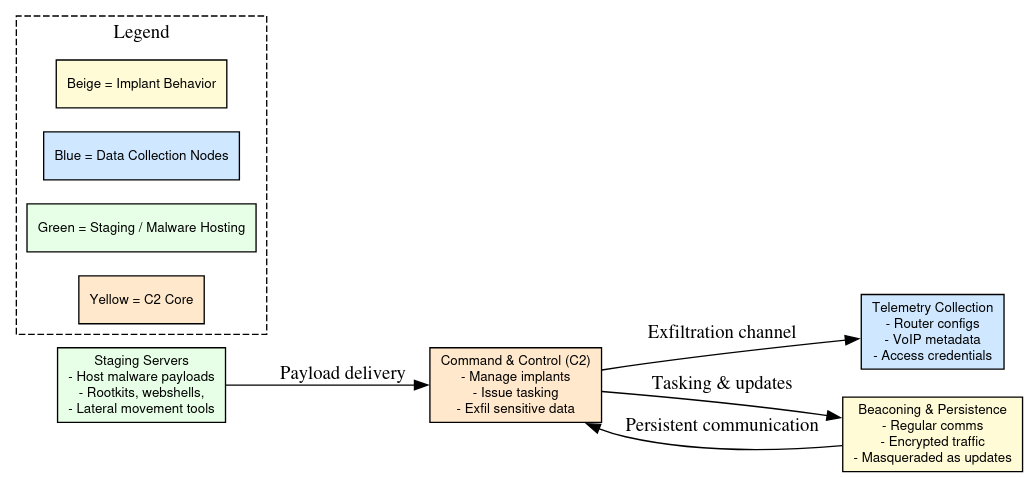

Campaign Architecture Model

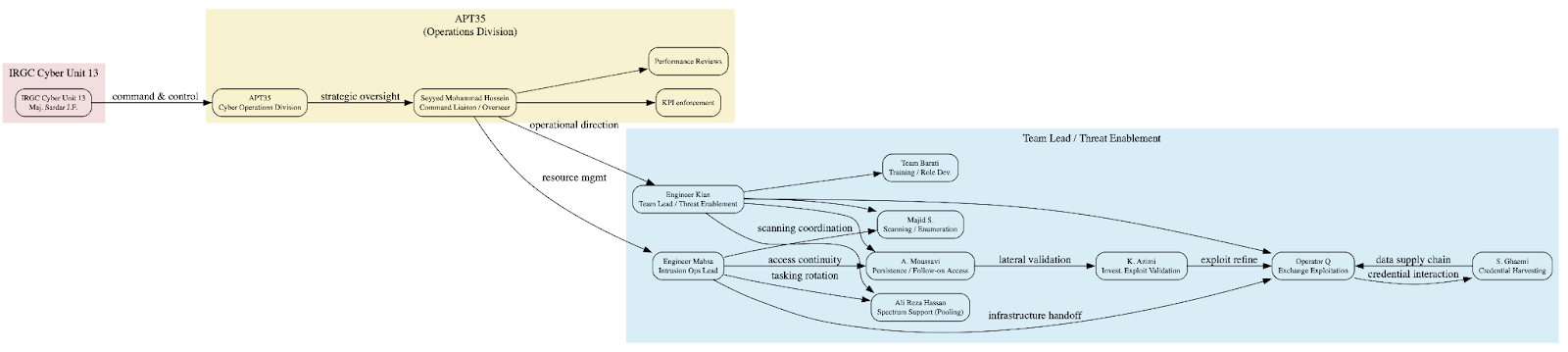

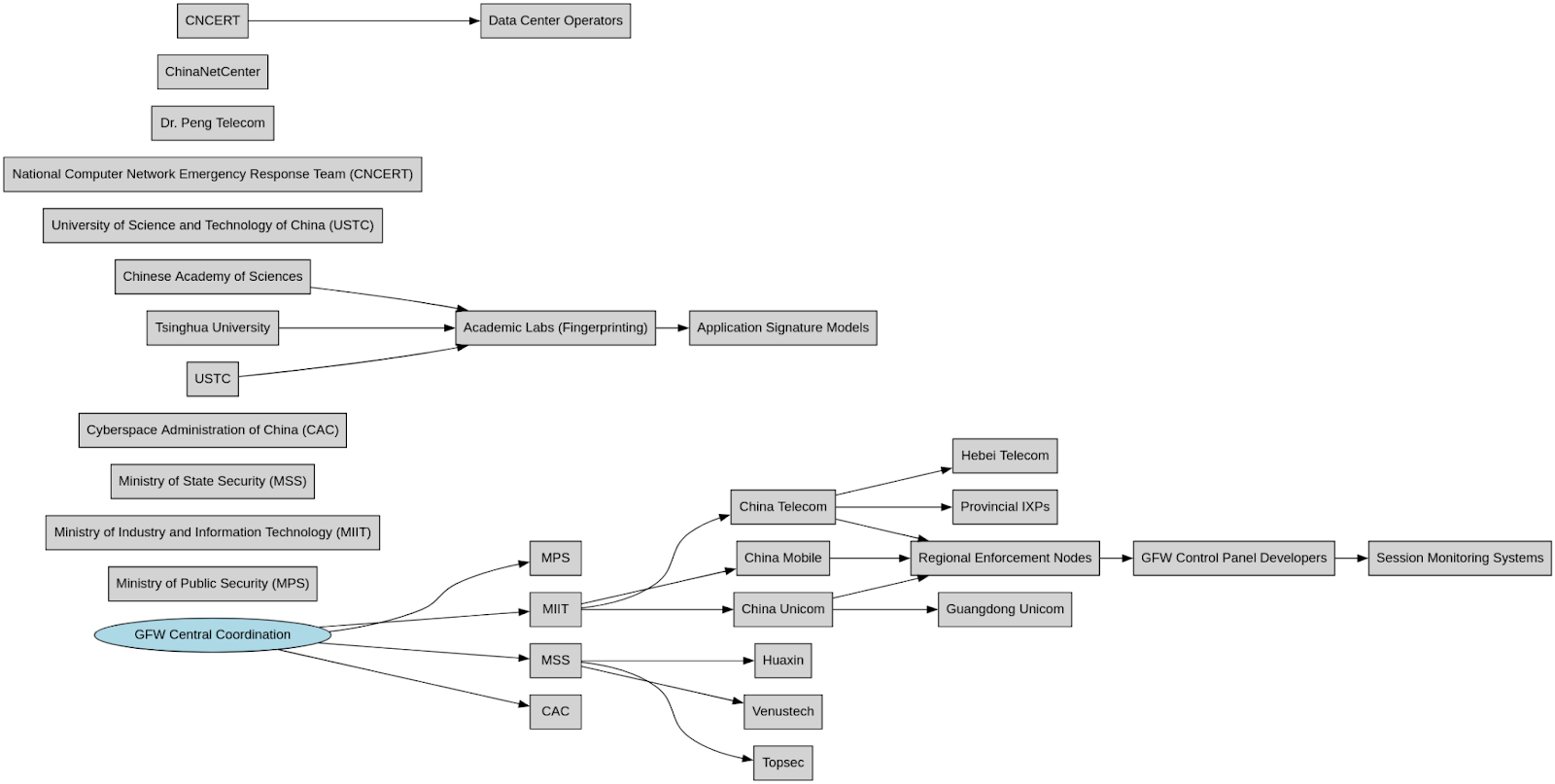

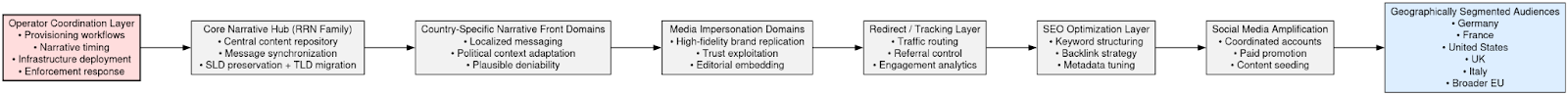

Across both structural reporting and dataset analysis, the campaign exhibits a deliberately layered and modular operational model. The architecture is not flat, nor is it improvisational. Instead, it reflects clear functional segmentation, with each tier responsible for a distinct operational objective.

At the apex sits an operator coordination layer. This tier likely manages provisioning workflows, narrative timing, infrastructure deployment, and enforcement response. It is the command-and-control plane of the information operation, though not in the malware sense; rather, it orchestrates domain registration cycles, publishing cadence, and geographic targeting priorities. This also shows the banality of disinformation being just a process driven means to a larger end in the global war on reality.

Beneath this layer resides the core narrative hub, anchored by the RRN domain family. This constellation functions as a central content repository and thematic synchronization point. It consolidates narratives, standardizes messaging frames, and acts as a reference anchor for downstream properties. When seizures occur, this hub migrates in controlled fashion, preserving continuity through second-level domain retention and TLD substitution.

Below the hub tier are country-specific narrative front domains. These properties localize messaging for particular audiences, adapting tone, framing, and political emphasis according to national context. They provide plausible deniability by presenting themselves as independent outlets, while remaining structurally tethered to the broader ecosystem.

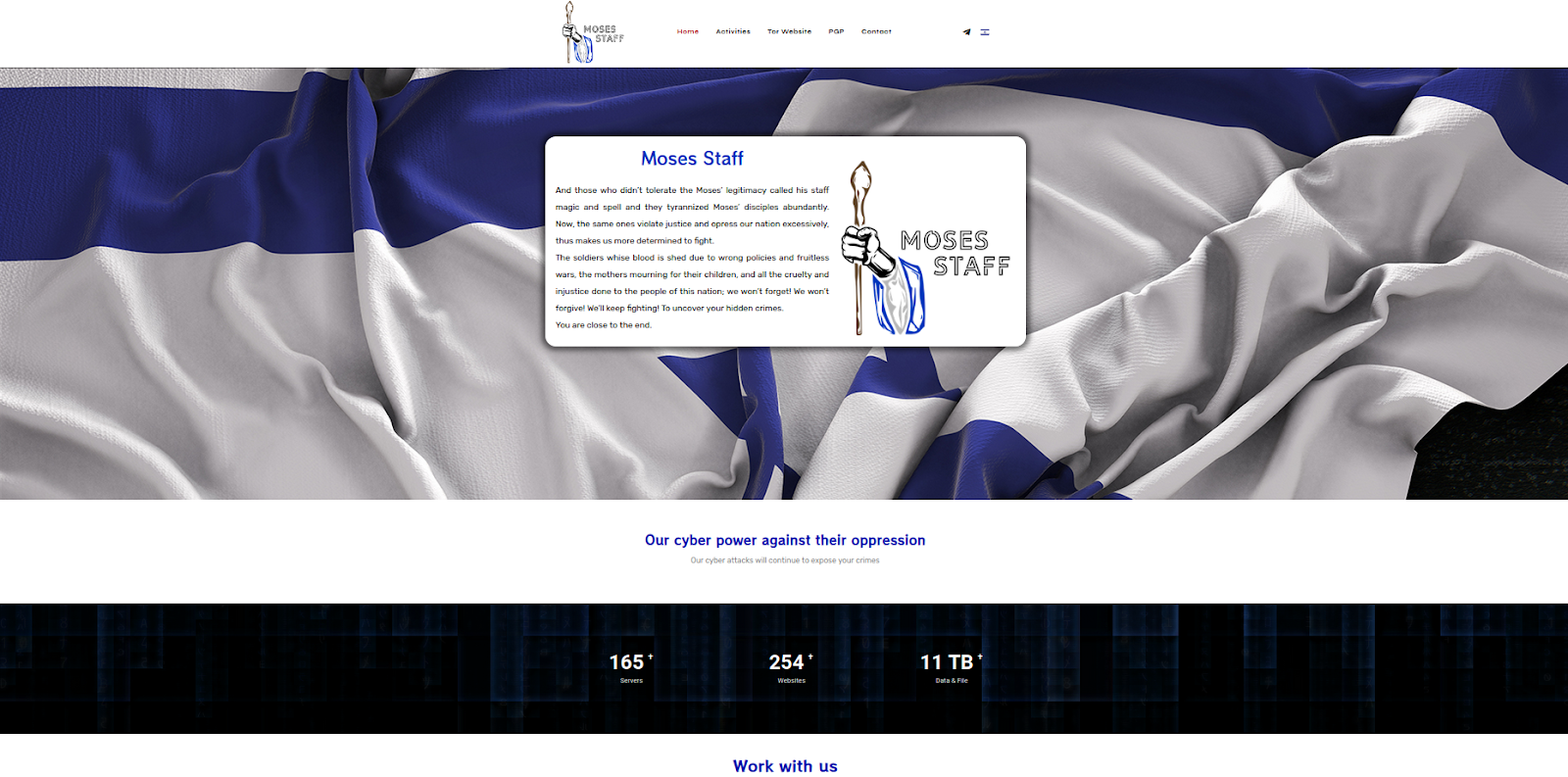

The next layer consists of media impersonation domains. These are the most visible components of the campaign, designed to replicate established Western media brands with high visual fidelity. Their purpose is brand deception: to exploit audience trust in recognizable outlets and to embed narratives within seemingly legitimate editorial environments.

Supporting these front-facing elements is a redirect and tracking layer. This tier manages traffic flow, referral routing, and possibly engagement analytics. It enables flexible amplification pathways and allows operators to shift traffic patterns without modifying core content nodes.

Above distribution sits the SEO optimization layer. Search visibility is engineered through keyword structuring, backlink strategies, and metadata tuning. This layer ensures that impersonation domains surface within search ecosystems, increasing organic discovery and enhancing perceived legitimacy.

Finally, social media amplification functions as the outermost dissemination ring. Coordinated accounts, paid promotion, or content seeding strategies drive traffic toward the impersonation domains. Social platforms act as accelerants, extending reach into geographically segmented audiences.

At the terminus of this layered model are the audiences themselves, segmented by geography and political context. Messaging is not broadcast uniformly; it is calibrated. German audiences receive different narrative emphasis than U.S. or French audiences, even when core themes remain aligned.

This architecture separates content generation, brand deception, distribution mechanics, and resilience engineering into discrete but interconnected layers. The result is a modular influence system capable of rapid reconfiguration. When one layer is disrupted, such as through domain seizure, the remaining tiers persist to enable continuity. This structural separation is a defining feature of the campaign’s operational maturity.

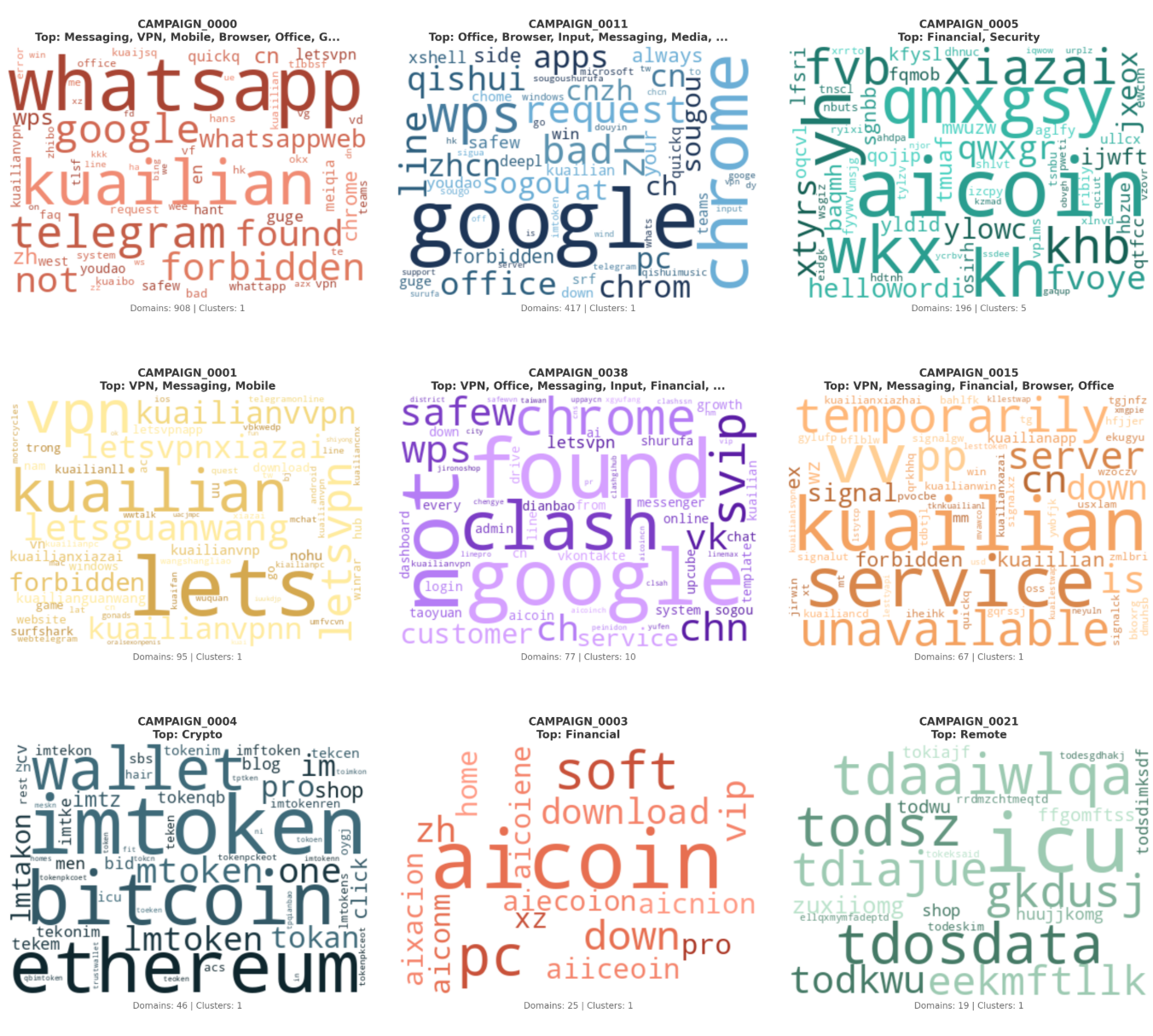

Domain Corpus & Structural Clustering

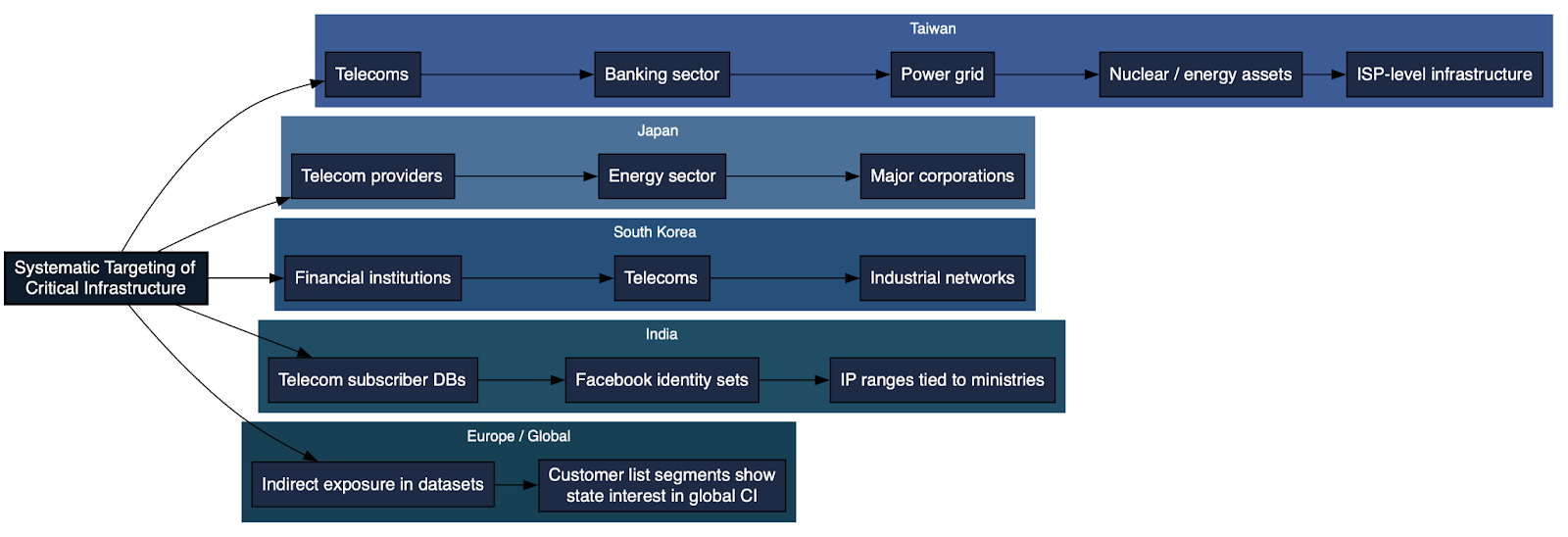

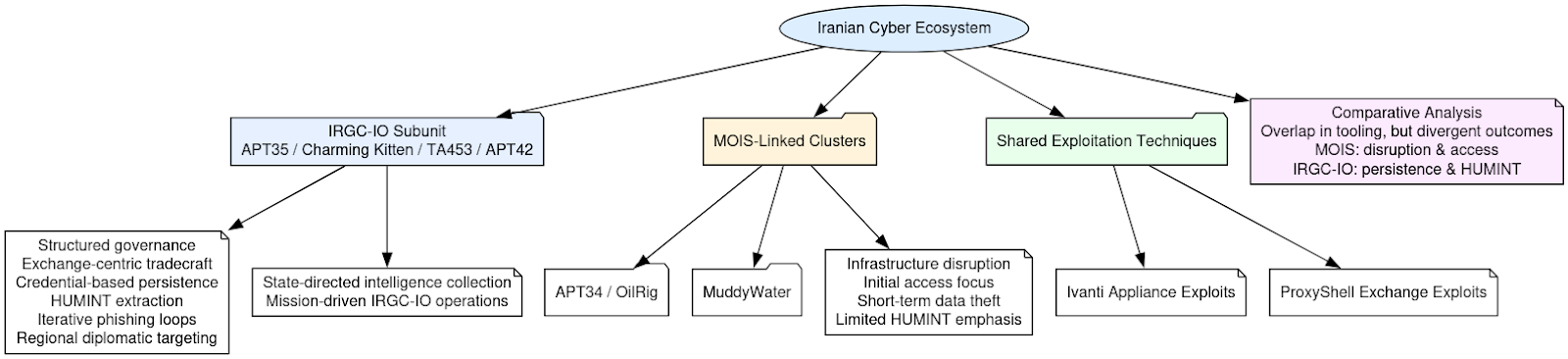

The domain ecosystem resolves into three principal structural tiers: core hubs, narrative fronts, and media impersonation clusters. Each tier performs a distinct operational role within the broader influence architecture.

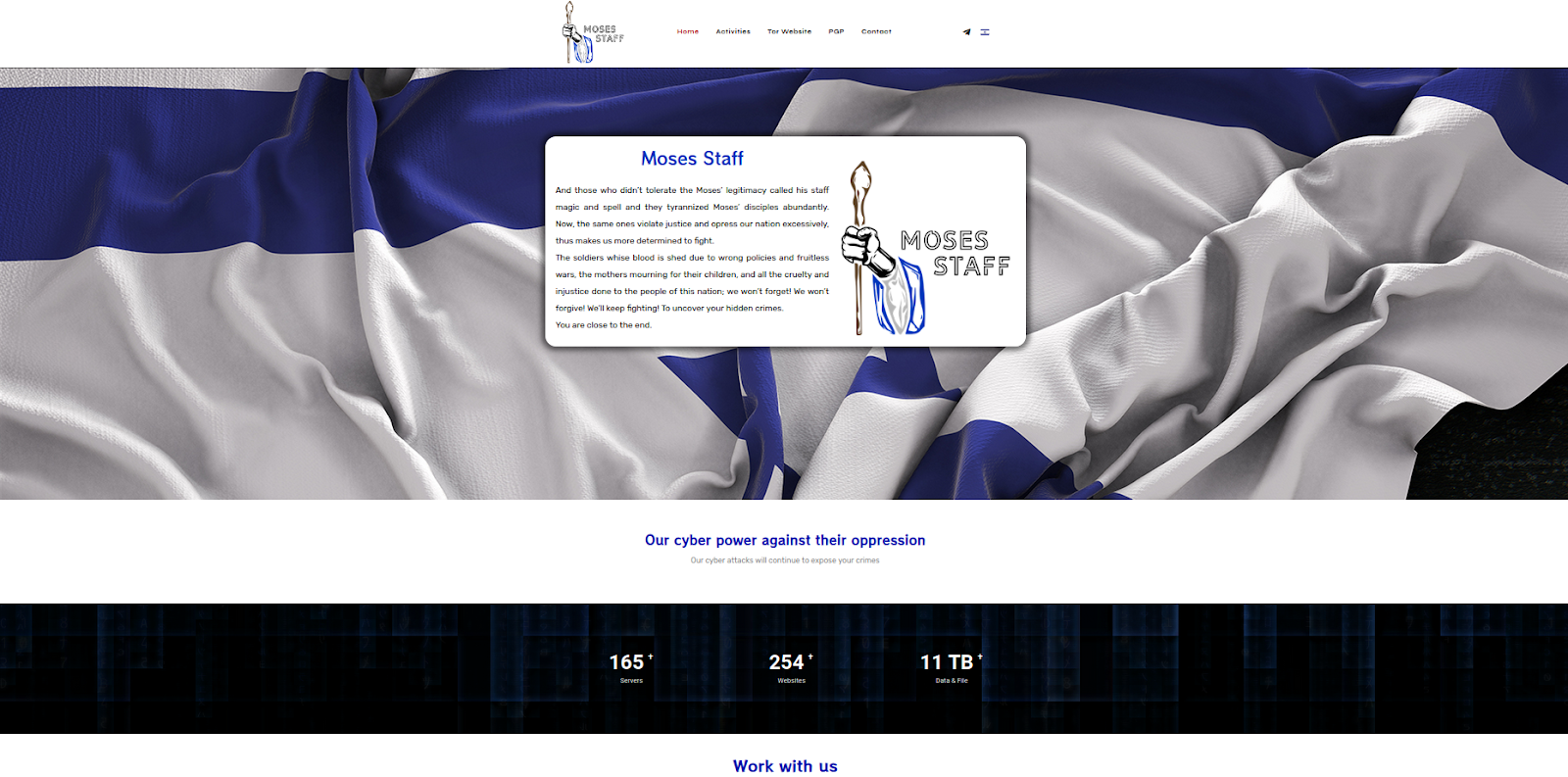

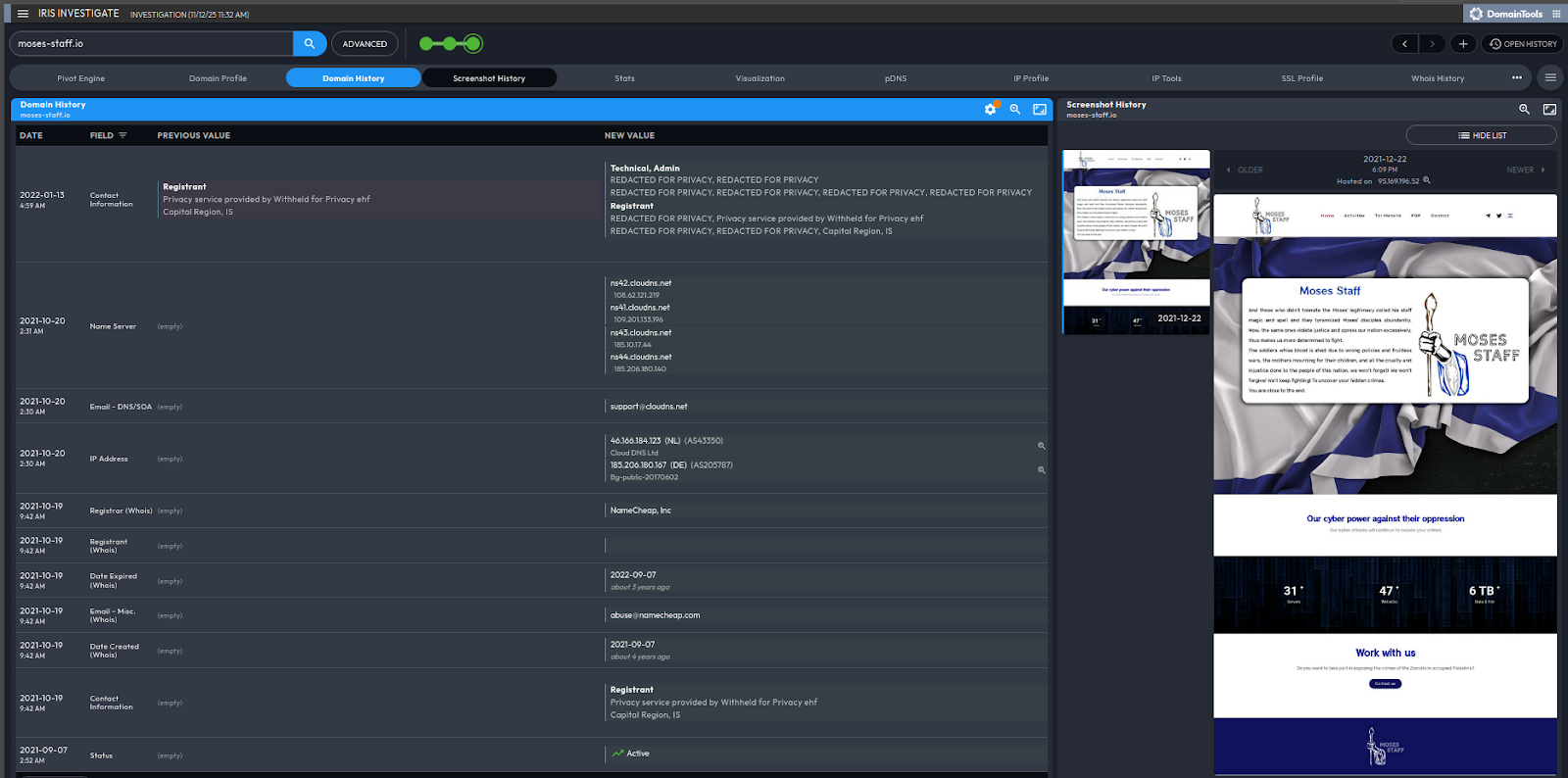

The core RRN hubs function as the gravitational center of the campaign. Observed anchors include rrn[.]world (2022-2025 * as of 2026 domain re-purposed by unknown entities exposing the doppelganger/SDA group), the previously seized rrn.media, its post-enforcement successor rrn[.]so, rrn[.]com[.]tr, and the earlier rrussianews[.]com. These domains operate as centralized narrative clearinghouses. They provide thematic consistency, content staging, and coordination continuity. When enforcement actions occur, the transition between domains preserves second-level naming conventions, indicating planned migration rather than reactive improvisation. The hub tier is not simply a publishing site; it is the synchronization layer for the ecosystem’s messaging and lifecycle management.

Beneath this central constellation sit the narrative front domains. Properties such as 50statesoflie., acrosstheline., avisindependent.eu, artichoc[.]cc, levinaigre[.]so, ukrlm[.]so, and shadowwatch[.]us are structured to appear as independent editorial outlets. Their purpose is reframing. Rather than overtly presenting RRN branding, they repackage aligned narratives under the veneer of autonomous journalism. This layer introduces plausible deniability and audience-specific tonality while remaining structurally tethered to the broader system. The naming conventions are less overtly imitative than the impersonation tier, but they are thematically suggestive, often invoking investigative or oppositional framing.

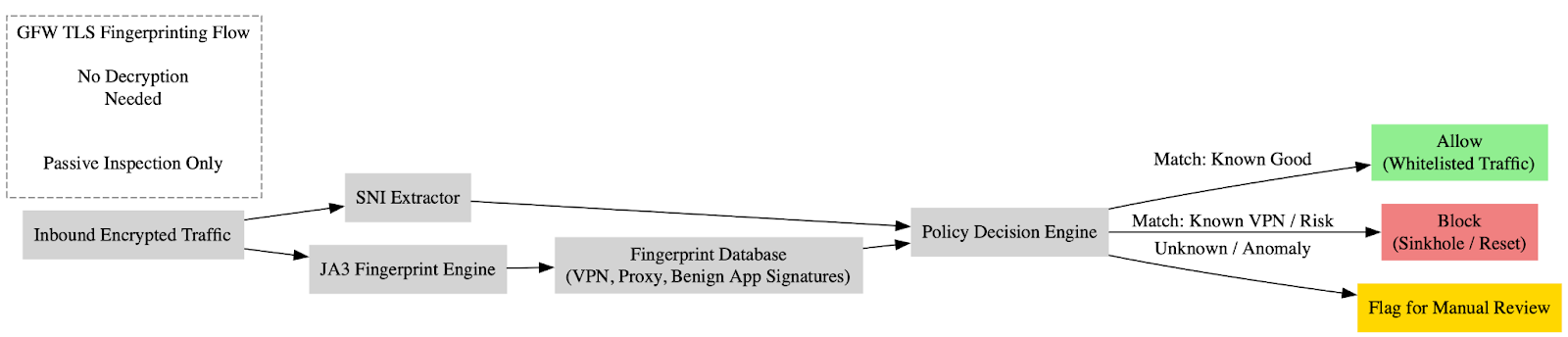

The largest and most visible component of the ecosystem is the media impersonation cluster, comprising approximately sixty percent of the observed domain corpus. This tier includes clones of prominent Western outlets such as Spiegel, Bild, Süddeutsche Zeitung, FAZ, Welt, T-Online, The Guardian, Daily Mail, ANSA, and variants referencing Fox News. These domains are engineered to replicate the visual and structural appearance of legitimate news brands, exploiting pre-existing public trust.

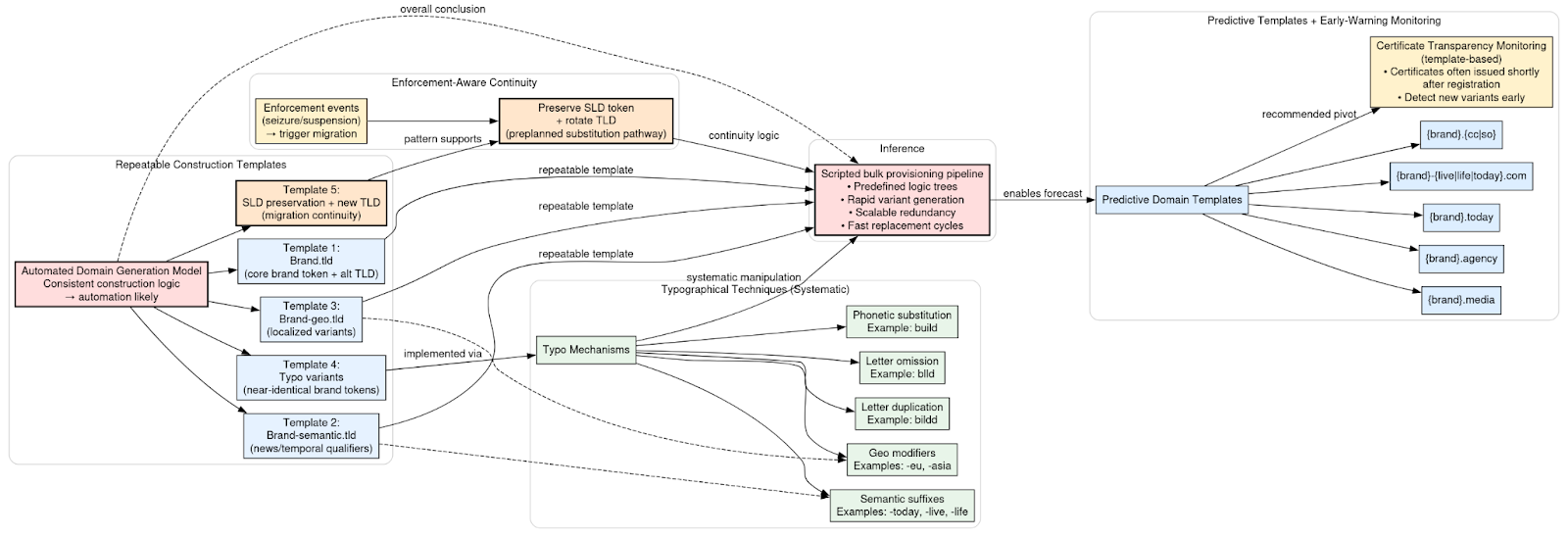

Impersonation within this cluster follows consistent technical patterns. Top-level domain substitution replaces primary brand extensions with lower-cost or less scrutinized alternatives. Typosquatting mechanisms include letter duplication, omission, and phonetic substitution, creating visually plausible but technically distinct domains. Additional variants employ brand-semantic suffixes or geographic modifiers to enhance credibility while maintaining differentiation from the authentic domain. The repetition and systematic variation across these brand families strongly suggest automated or scripted domain generation logic rather than manual, ad hoc spoofing.

Taken together, these three tiers illustrate a graduated deception model. The core hubs centralize narrative control. The narrative fronts contextualize and reframe messaging under independent branding. The impersonation clusters maximize credibility exploitation through high-fidelity replication. The structural coherence across all three layers reinforces the conclusion that this is a coordinated provisioning ecosystem rather than isolated instances of media spoofing.

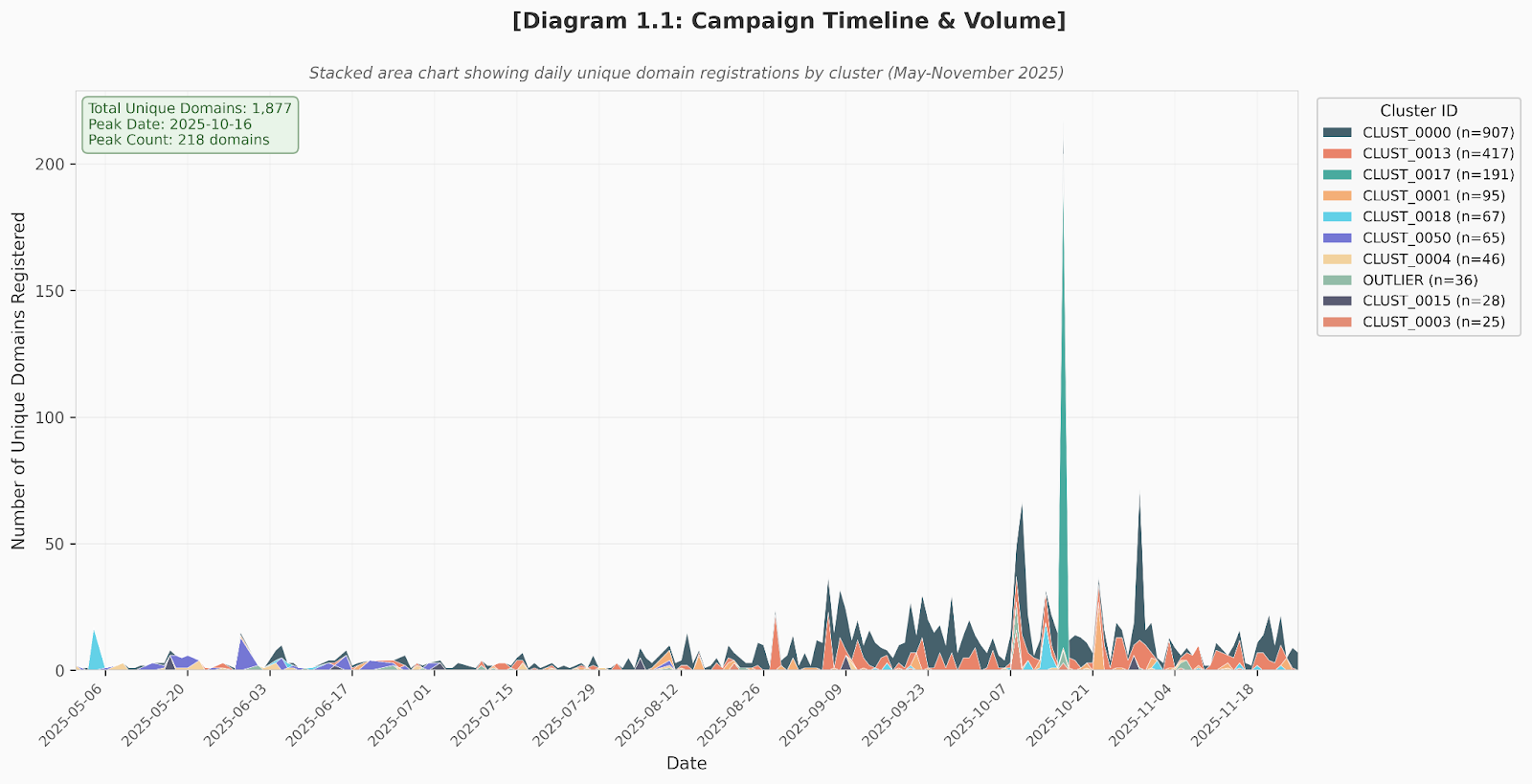

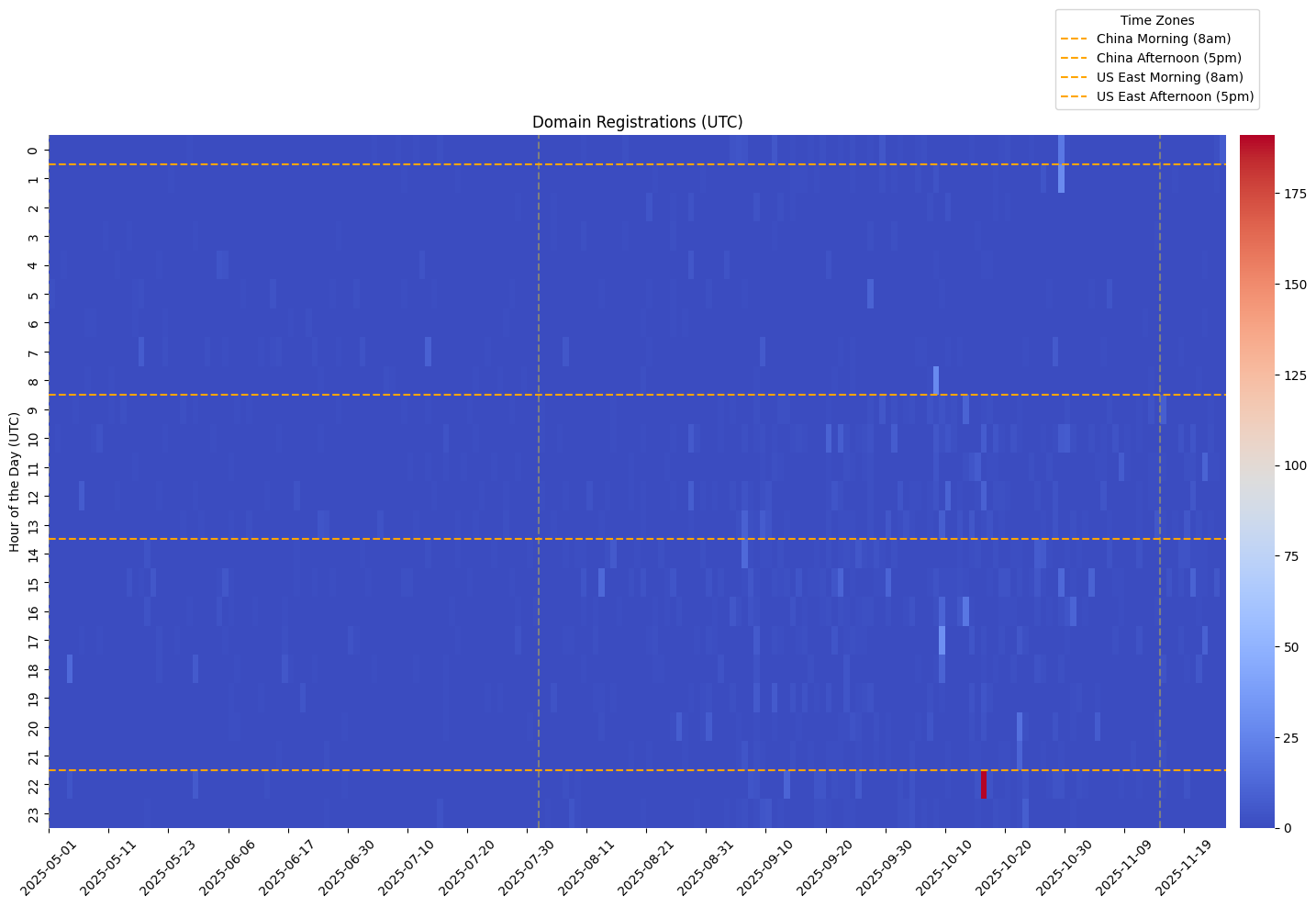

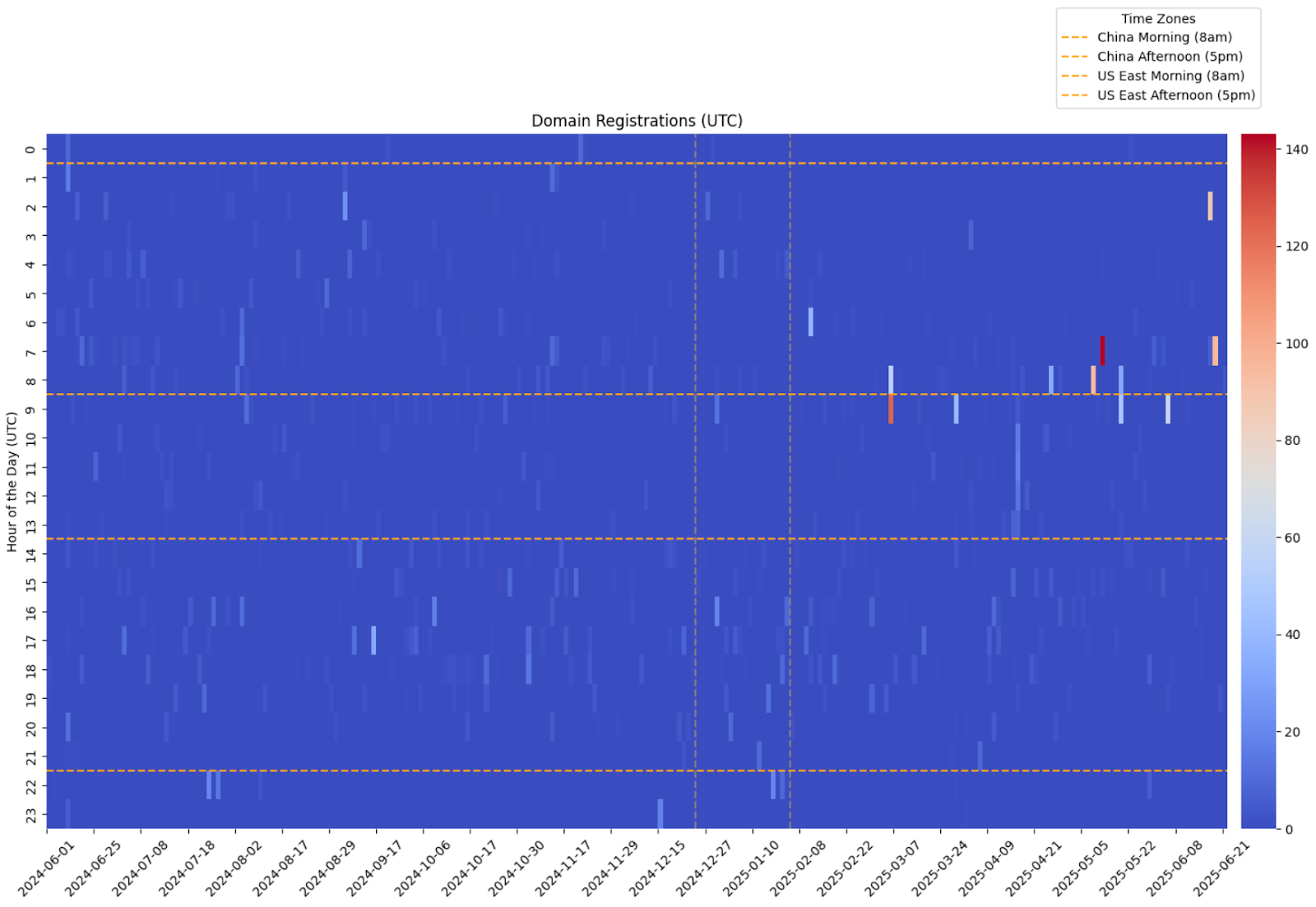

Temporal analysis of the 48-domain dataset reveals that domain acquisition did not occur as a continuous or organic process. Instead, registrations cluster into two distinct provisioning bursts, each aligned with identifiable geopolitical inflection points.

The first wave occurred in mid-2022, coinciding with the escalation phase of the war in Ukraine. During this period, domain registrations expanded rapidly across multiple brand families and narrative fronts. The timing suggests synchronization with heightened geopolitical tension and intensified information competition. Rather than opportunistic spoofing, the burst reflects pre-coordinated deployment intended to support sustained narrative operations during a critical phase of the conflict.

The second wave emerged in September 2024. This provisioning cycle aligns with Western electoral timelines and follows public enforcement actions targeting earlier Doppelgänger infrastructure. The pattern indicates both narrative refresh and infrastructure regeneration. Domains registered during this period show evidence of replacement logic, TLD diversification, and continued brand-family clustering, consistent with an adaptive response to seizure activity.

Across both waves, several structural characteristics remain consistent. Registration timestamps fall within narrow windows, suggesting batch provisioning rather than independent acquisition. Multiple domains tied to the same media brand families appear within close temporal proximity, reinforcing the likelihood of centralized control. The recurrence of identical naming logic across separate waves further indicates a reusable deployment pipeline.

This temporal clustering model is incompatible with organic domain growth. Instead, it reflects planned campaign staging cycles in which infrastructure is provisioned in anticipation of narrative events or in response to enforcement disruption. The pattern is consistent with structured influence operations that operate in defined phases rather than continuous improvisation.

TLD Strategy & Enforcement Evasion

Analysis of top-level domain selection reveals a deliberate concentration in a specific family of extensions. Dominant TLDs across the ecosystem include .media, .agency, .ltd, .today, .life, .ws, .cc, .so, .beauty, .expert, .vip, .pics, and .top. The distribution is neither random nor purely aesthetic; it reflects operational utility.

These extensions share several characteristics. They are generally low in acquisition cost, widely available at scale, and subject to comparatively limited scrutiny relative to legacy TLDs. Many also carry news-semantic or quasi-professional connotations such as .media, .agency, .today, or .expert which enhance surface credibility when paired with recognizable media brand tokens. This semantic plausibility increases the likelihood that users will perceive the domains as legitimate news outlets rather than synthetic replicas.

The selection pattern also supports rapid provisioning and replacement. Because these TLDs are typically less saturated than primary brand equivalents, operators can register multiple variants quickly and in batch. This flexibility is critical to enforcement resilience.

Observed seizure-to-migration behavior reinforces this assessment. When rrn[.]media was disrupted, operations pivoted to rrn[.]so while preserving the second-level domain. Similarly, 50statesoflie[.]com reappeared under .cc and .so variants, and acrosstheline[.]press transitioned to a .cc counterpart. In each case, the second-level domain remained intact while only the top-level extension changed.

Preservation of the second-level domain across new TLDs constitutes a very high-confidence linkage signal. It demonstrates continuity of operator control and planning rather than independent replication. The pattern indicates that alternate TLDs were likely pre-positioned or rapidly provisioned using the same deployment pipeline. This TLD substitution model is therefore not merely a branding choice; it is a resilience mechanism embedded within the infrastructure strategy.

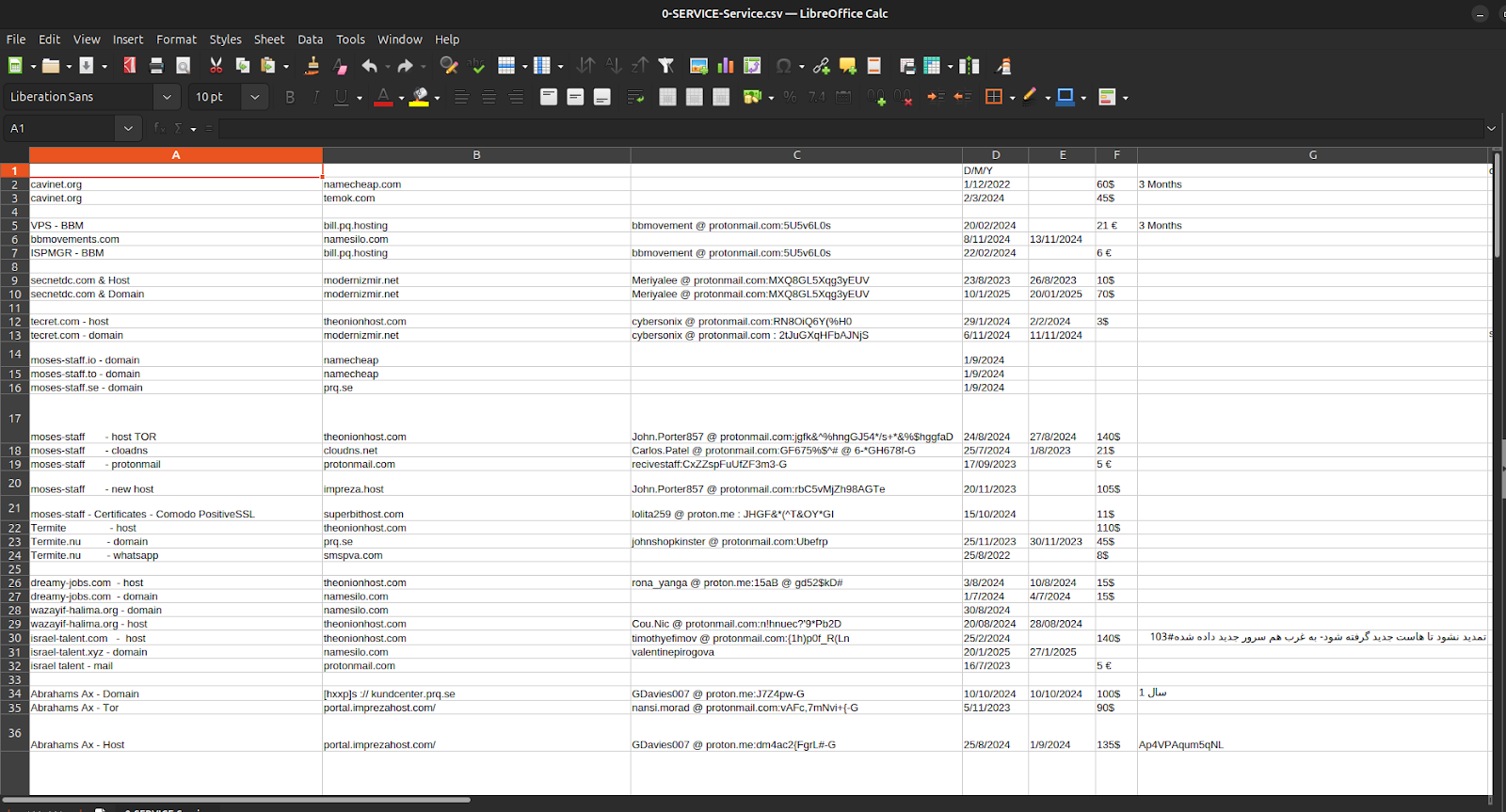

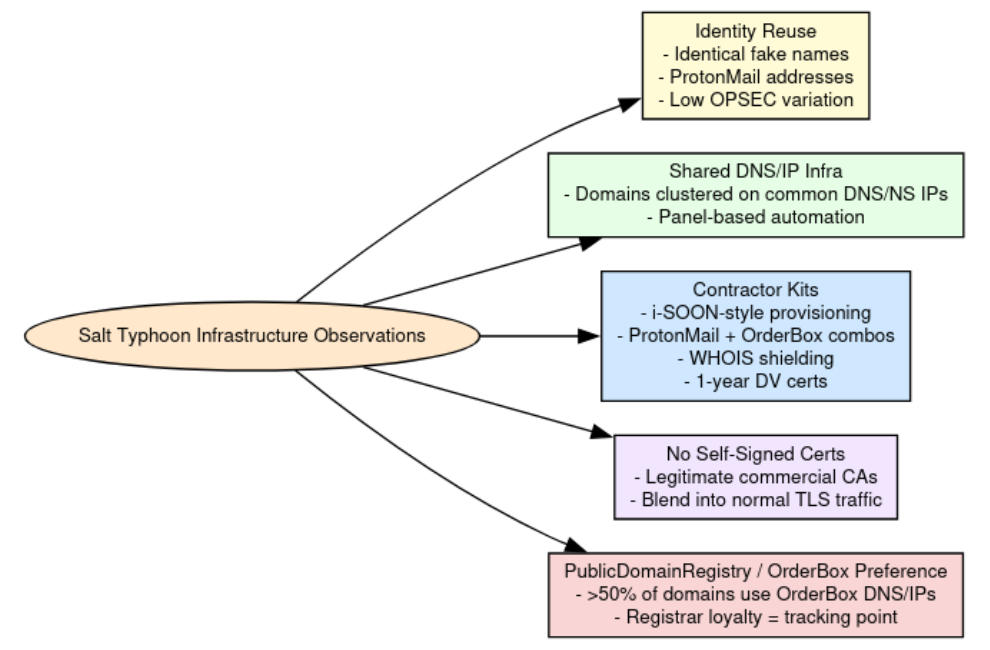

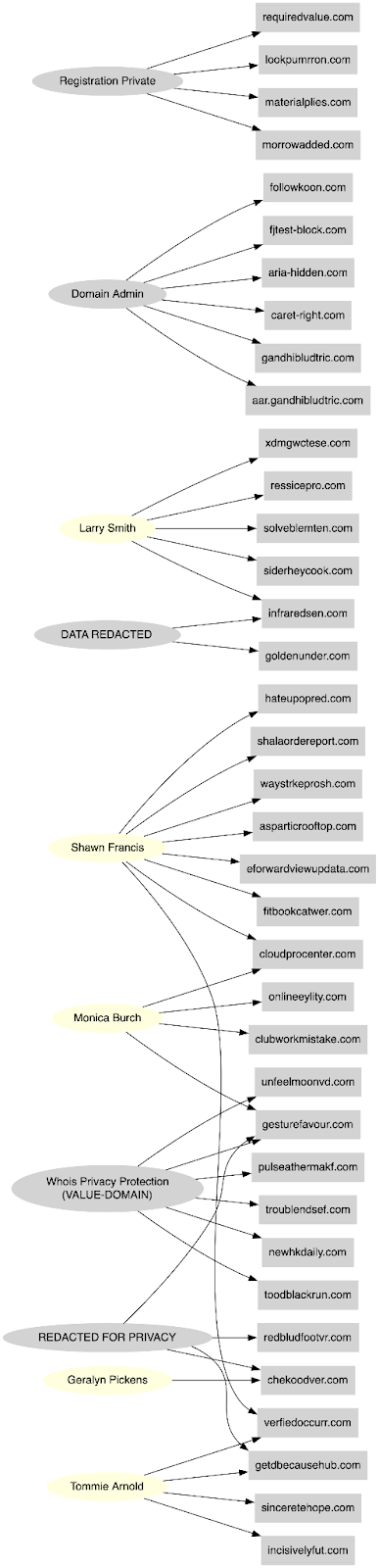

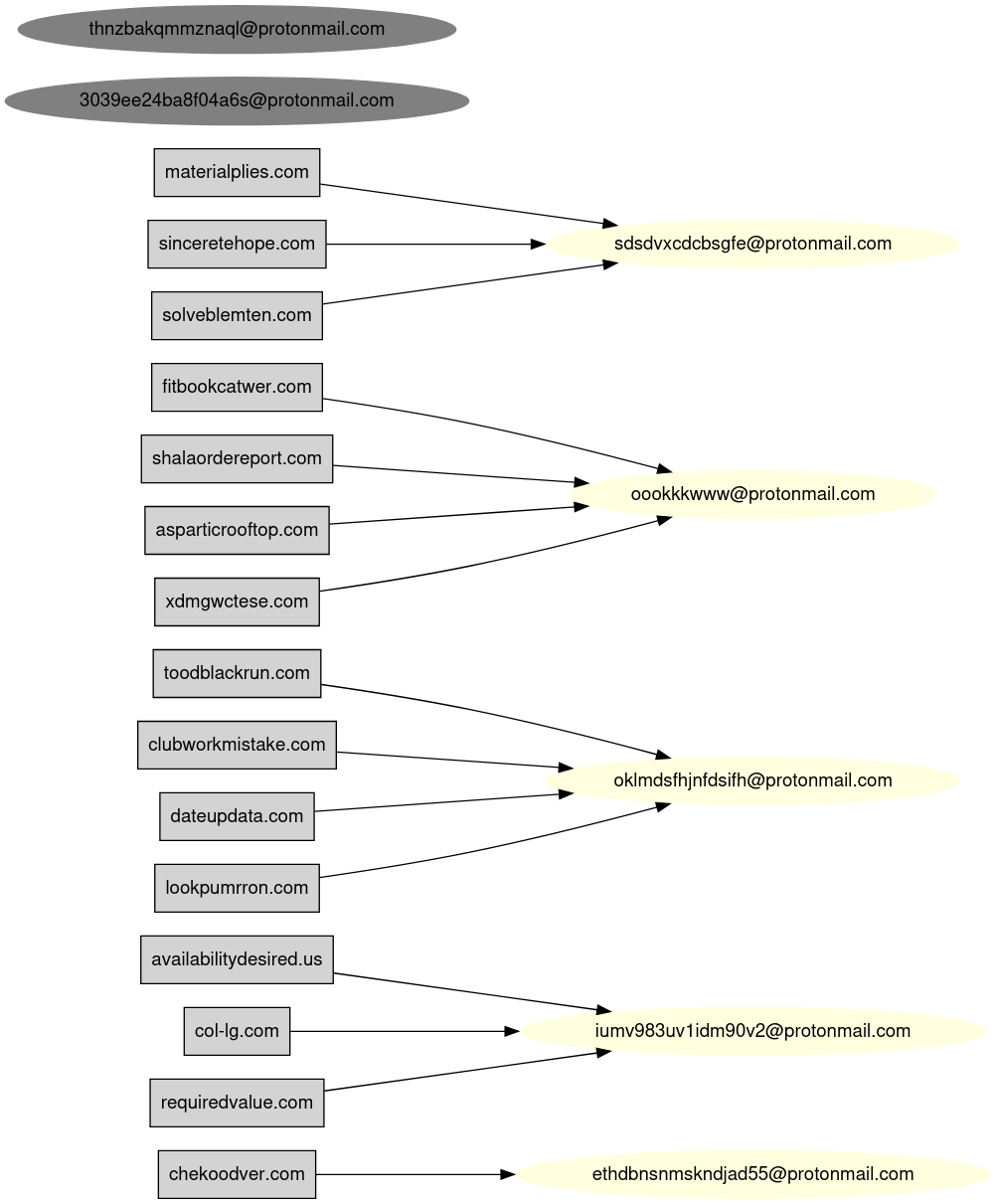

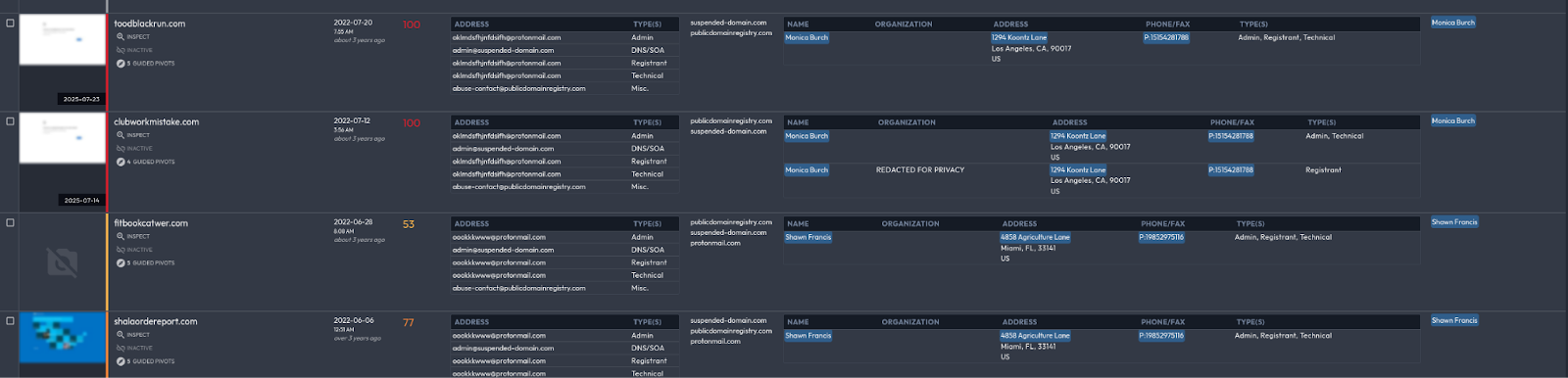

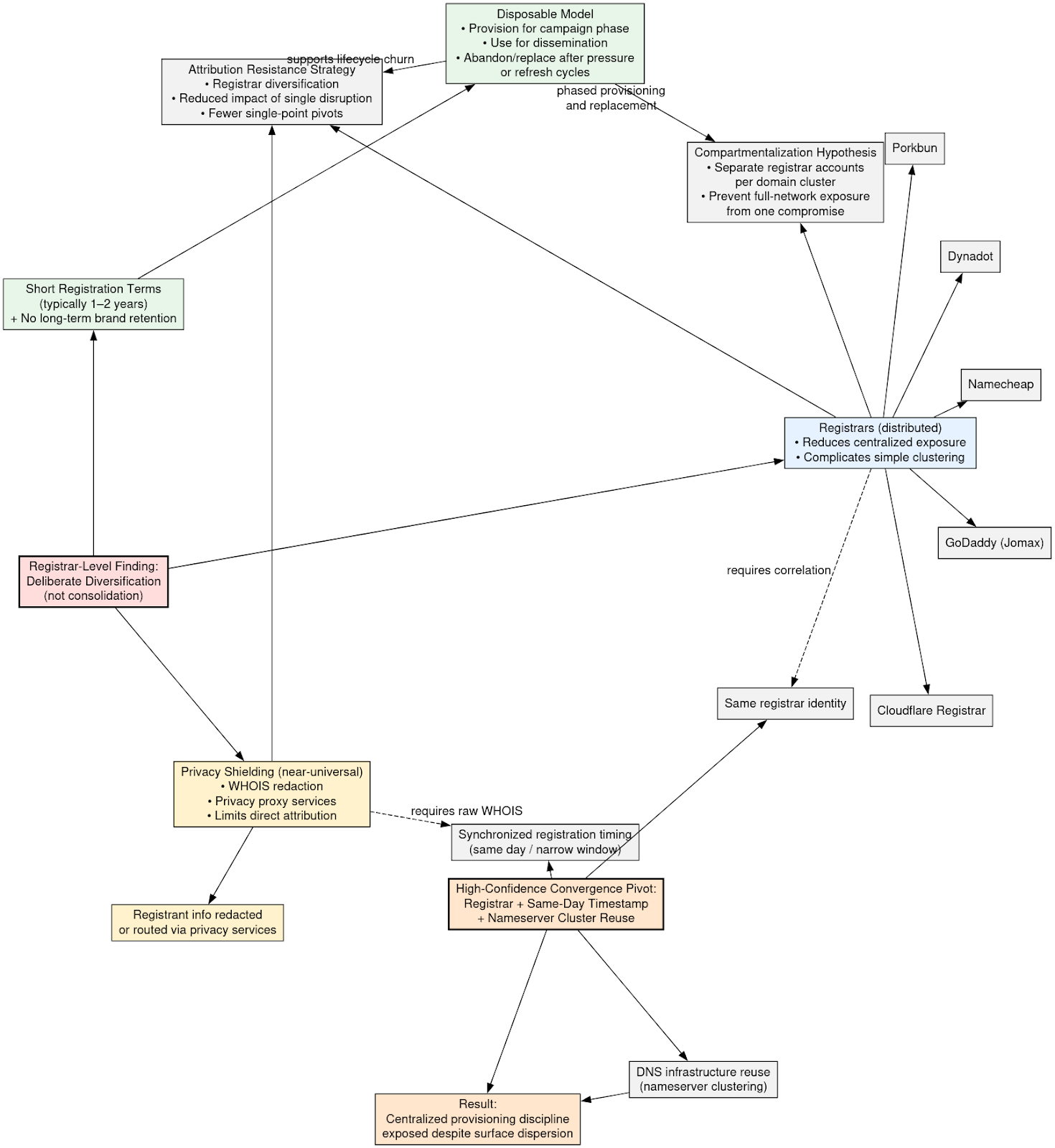

Registrar & Registration Patterns

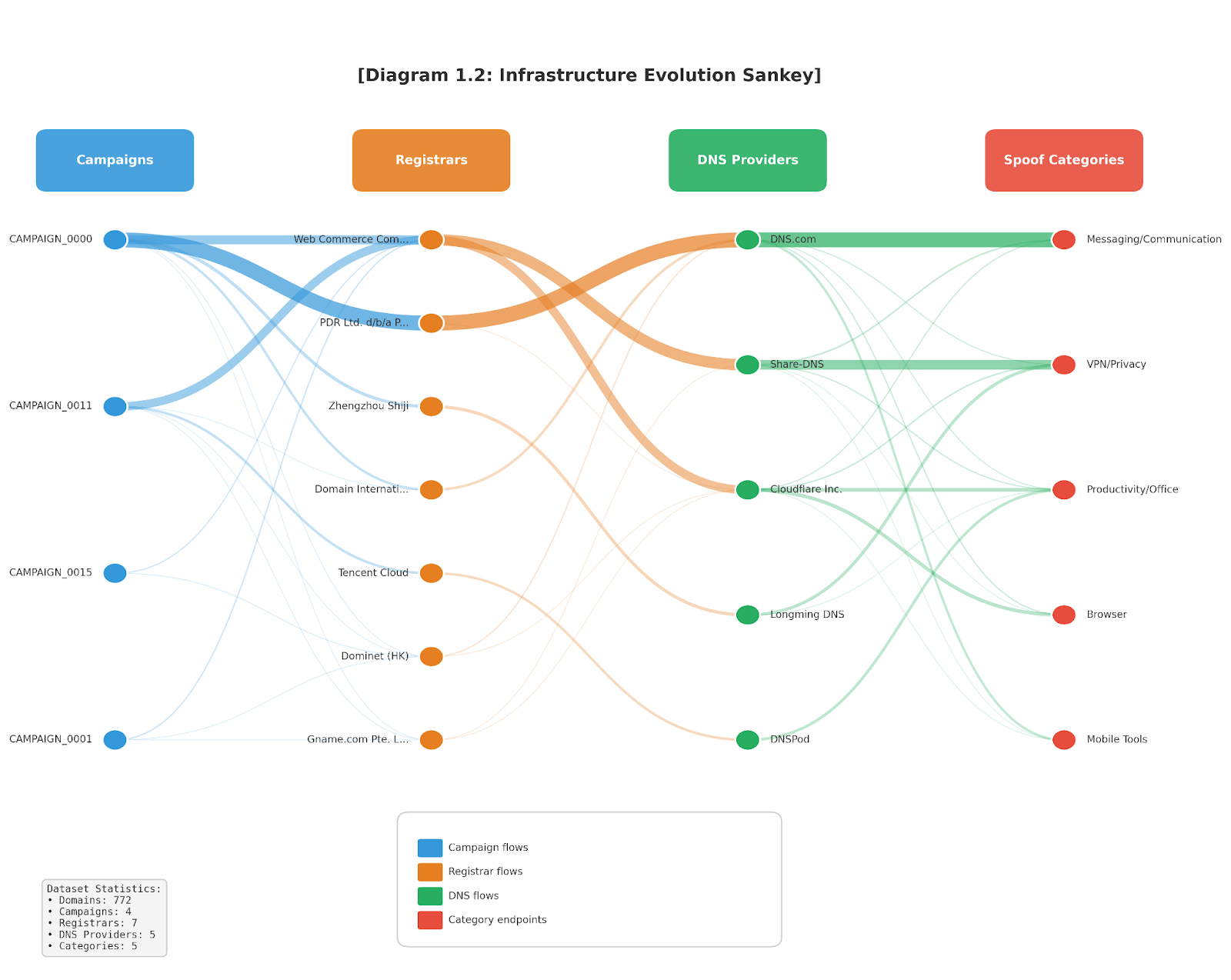

Registrar-level analysis indicates deliberate diversification rather than consolidation. Domains within the ecosystem are distributed across multiple commercial registrars, including Cloudflare, GoDaddy (Jomax), Namecheap, Dynadot, and Porkbun. No single registrar dominates the corpus. This dispersion reduces the likelihood of centralized administrative exposure and complicates straightforward clustering based on registrar account identifiers alone.

Privacy shielding is applied almost universally. Registrant information is redacted or routed through privacy services, limiting direct attribution vectors. Registration durations are typically short, most commonly one- to two-year terms, reinforcing the disposable nature of the infrastructure. There is no evidence of long-term brand cultivation or multi-year strategic retention of primary domains. Instead, domains appear engineered for limited operational lifespan, with replacement assumed as part of the lifecycle model.

Taken together, these characteristics support a strategy of attribution resistance through registrar diversification. By spreading registrations across multiple providers, the operators reduce the impact of any single registrar-level disruption or investigative pivot. This also suggests compartmentalization: different domain clusters may be provisioned under separate registrar accounts to prevent a single compromise from exposing the full network.

The lifecycle management model is explicitly disposable. Domains are provisioned for campaign phases, used for narrative dissemination, and abandoned or replaced following enforcement pressure or strategic refresh cycles. This is consistent with burst registration waves and TLD substitution behavior observed elsewhere in the ecosystem.

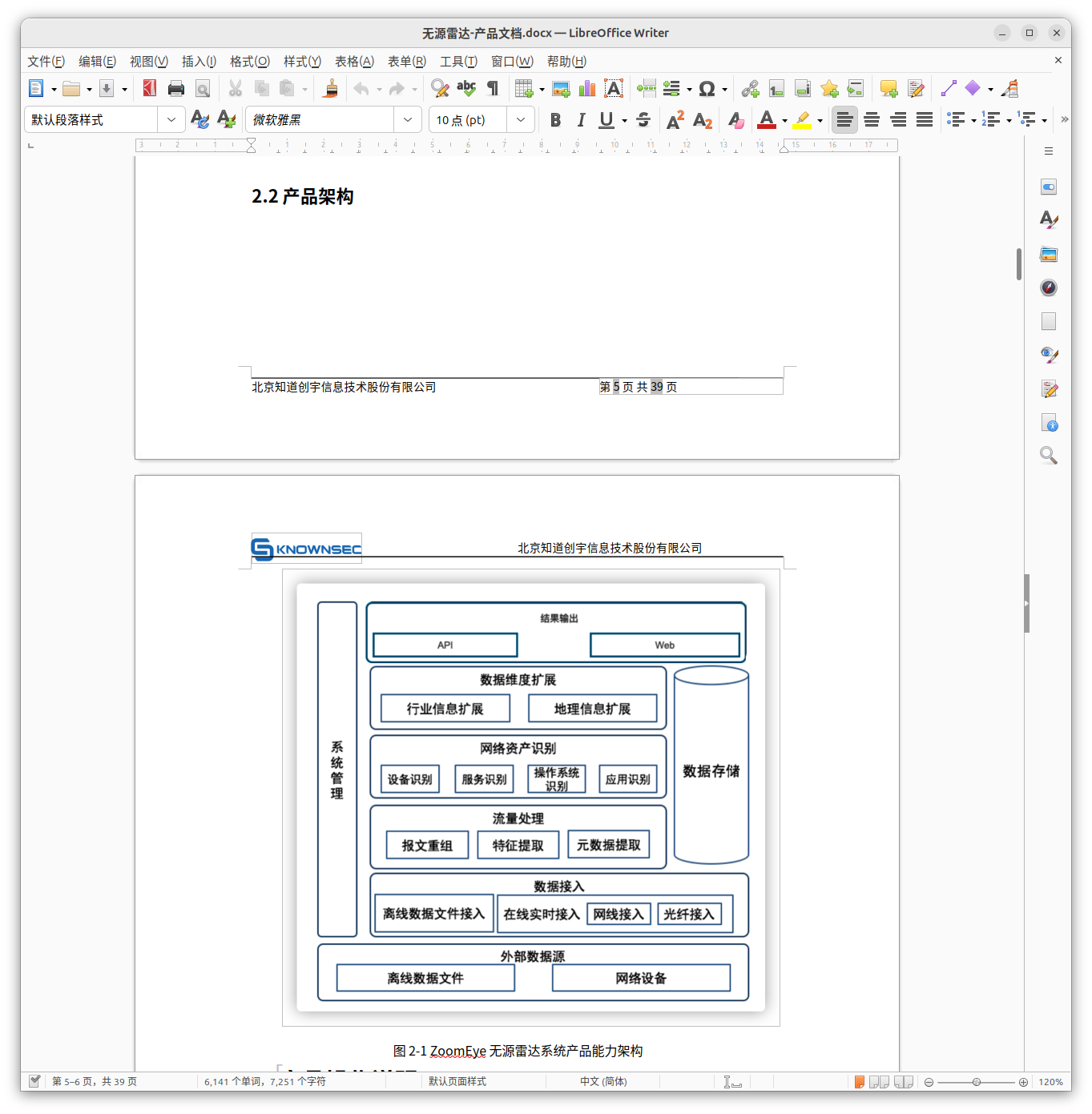

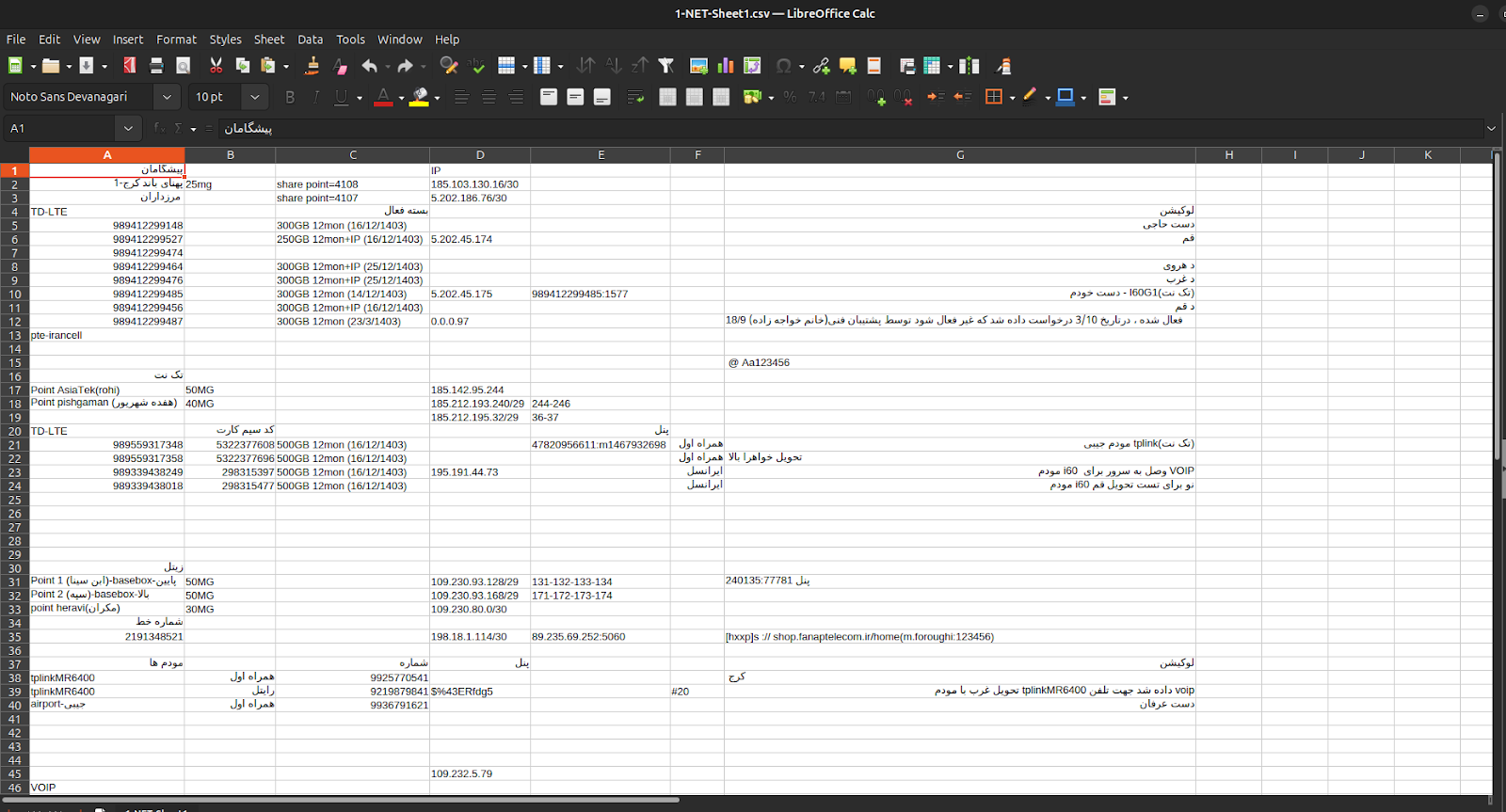

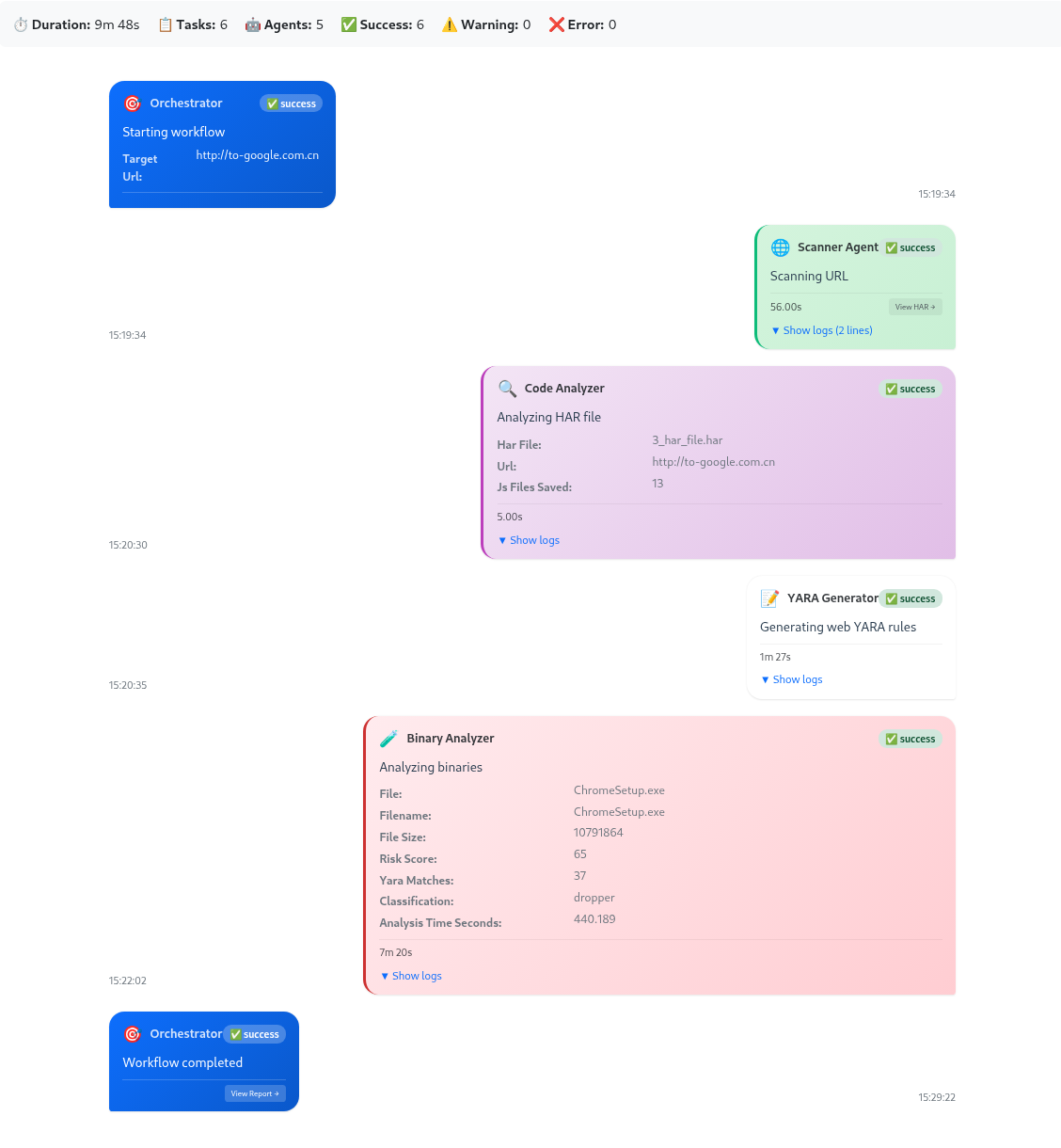

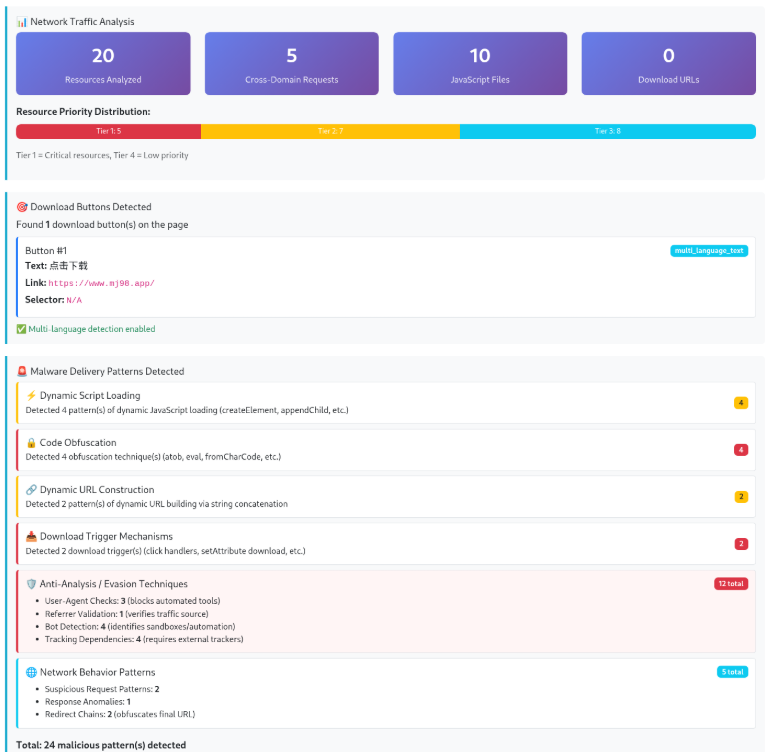

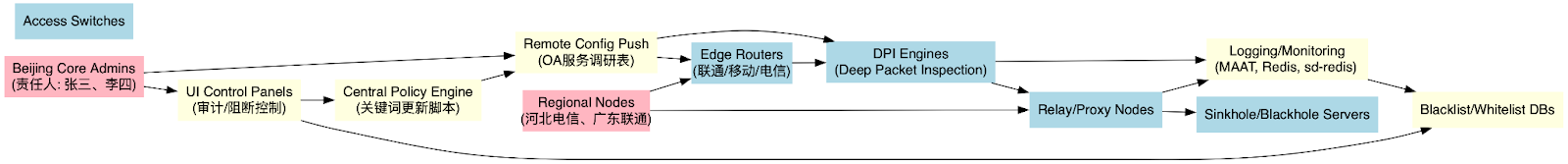

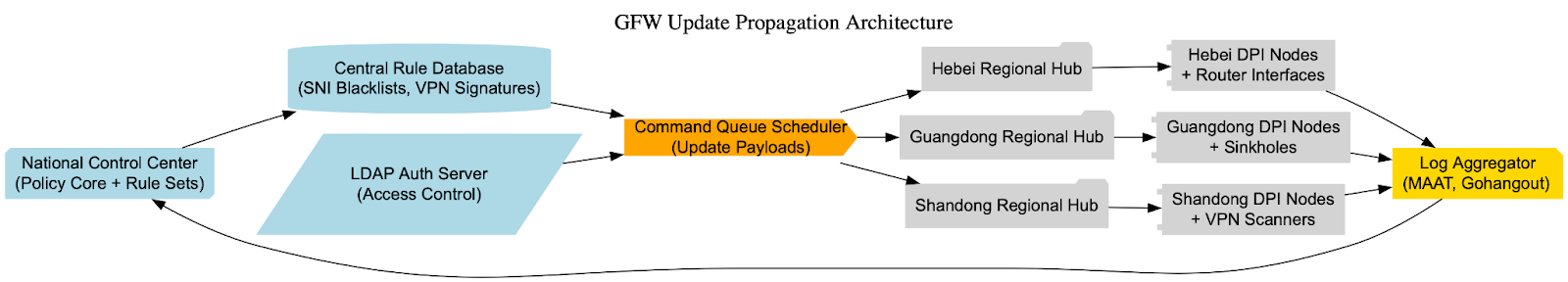

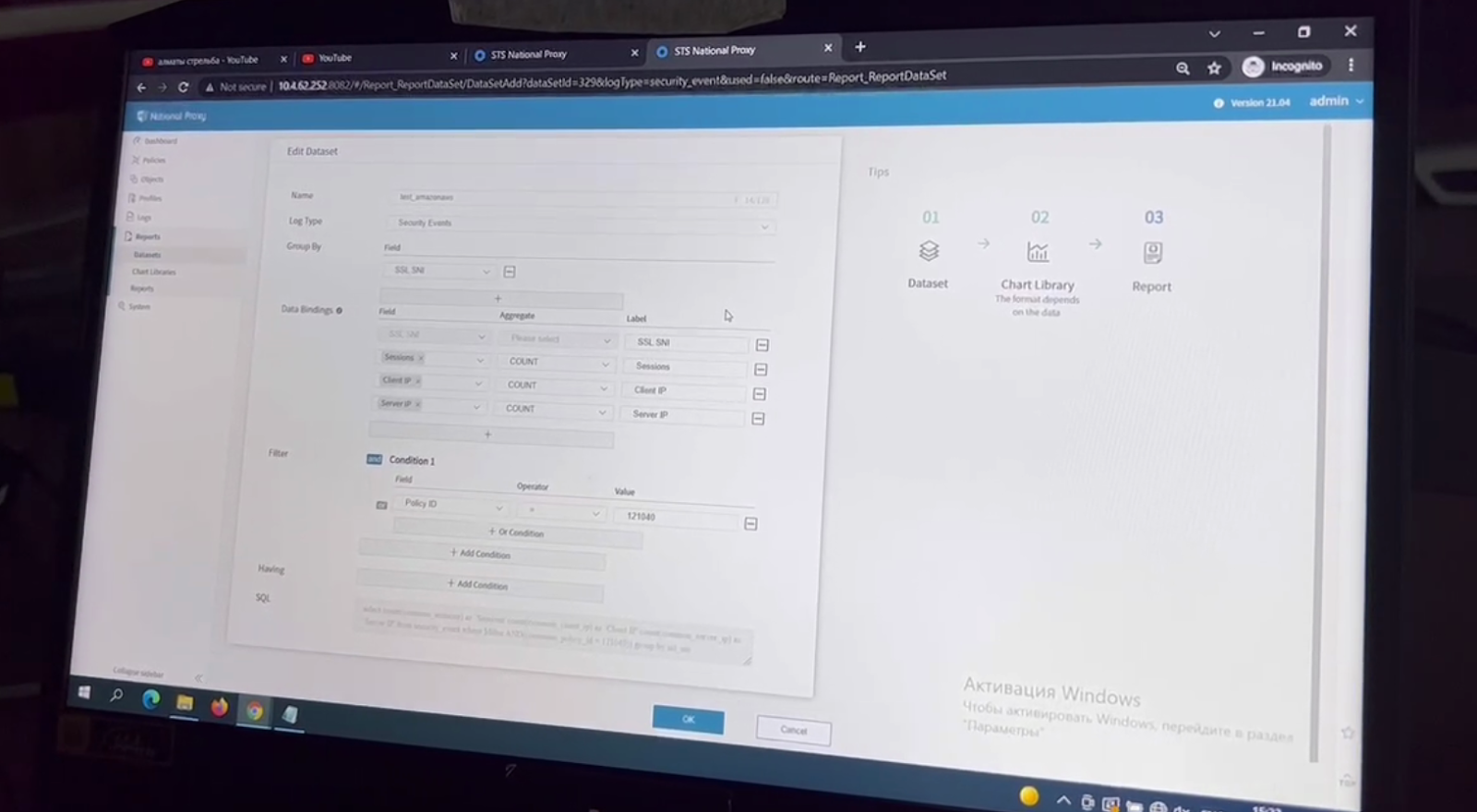

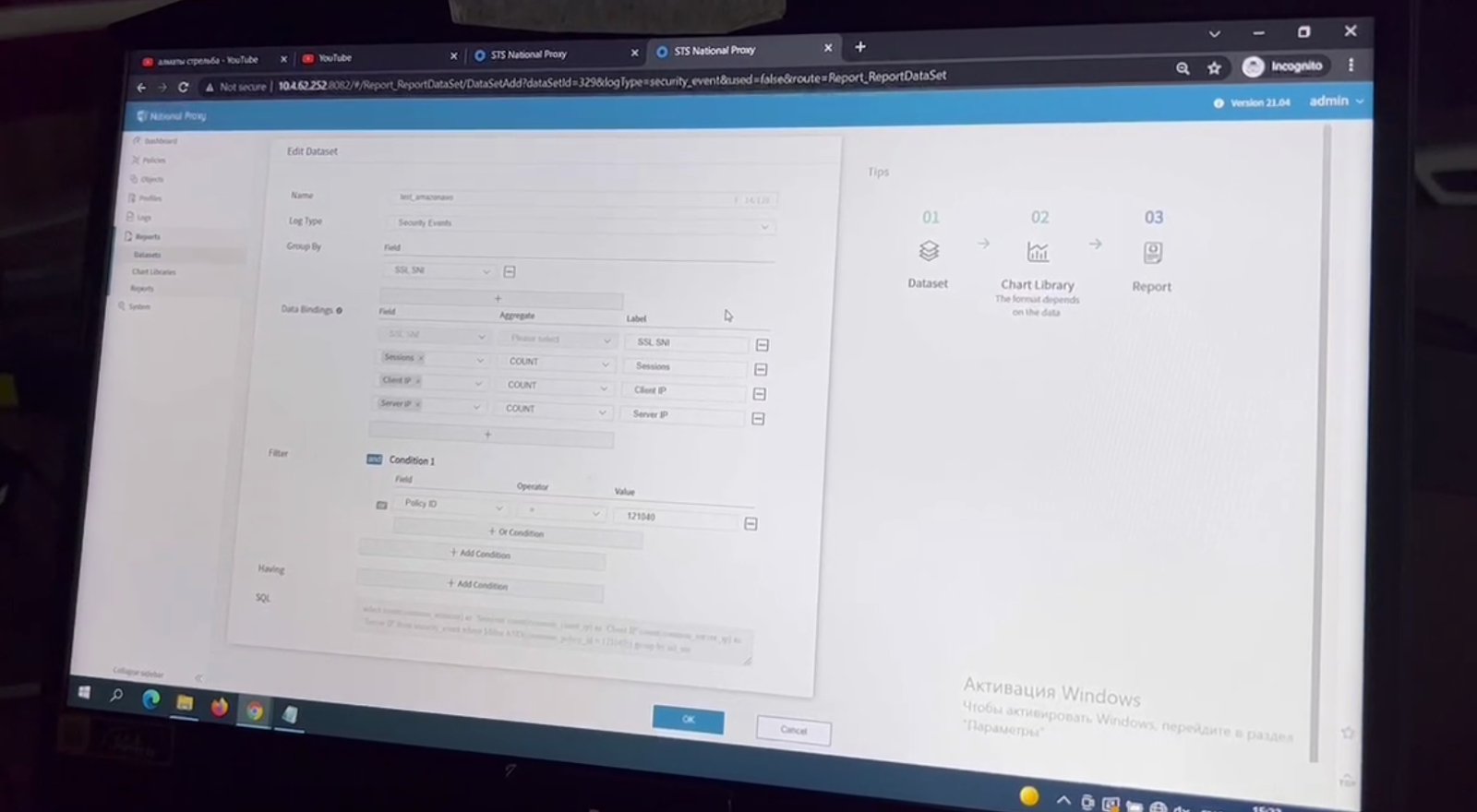

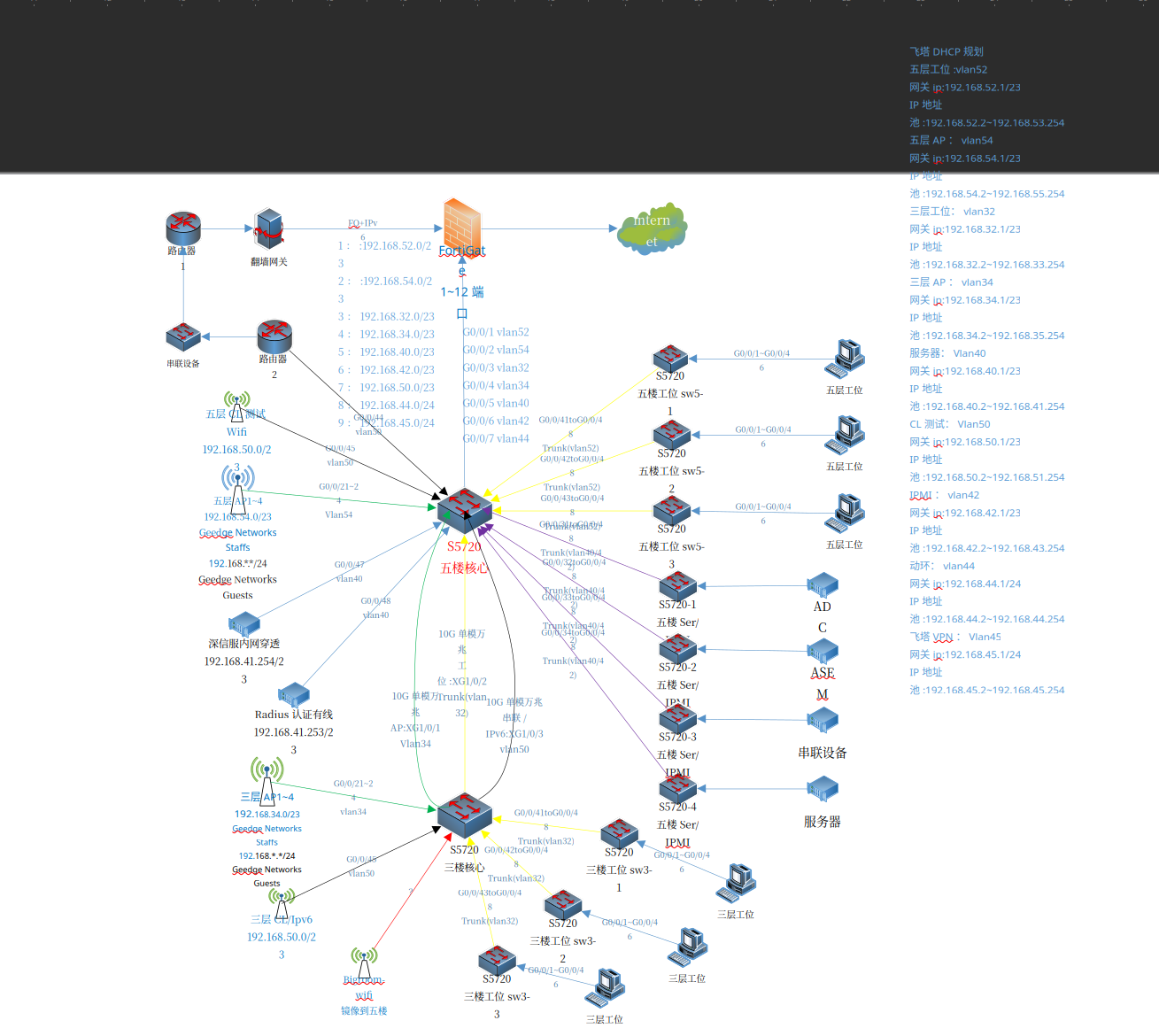

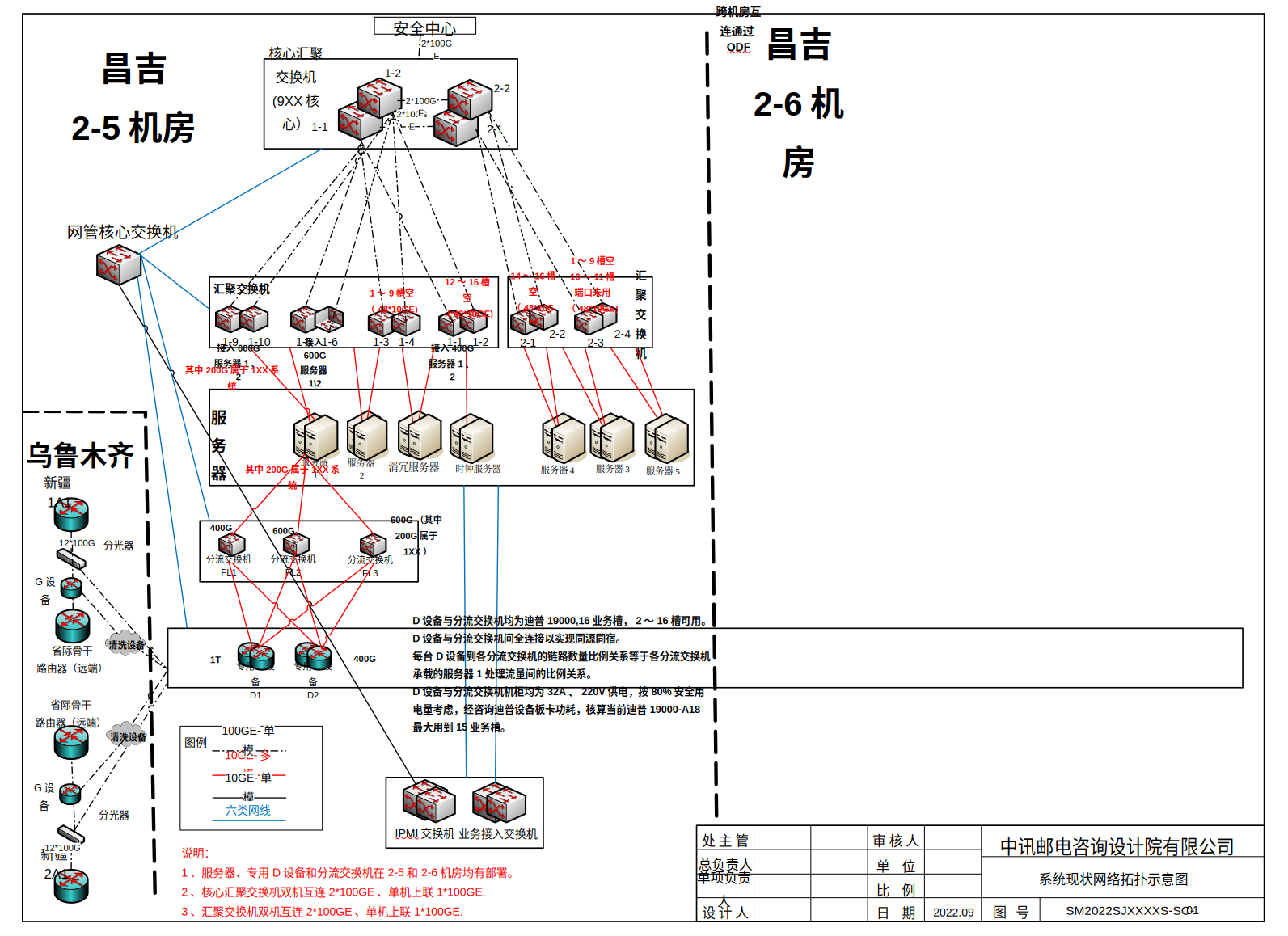

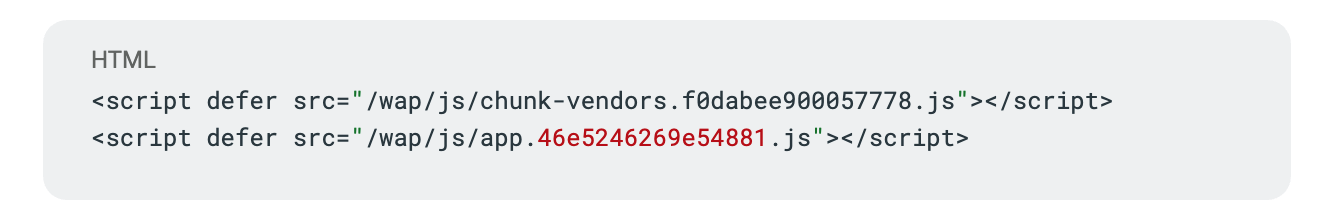

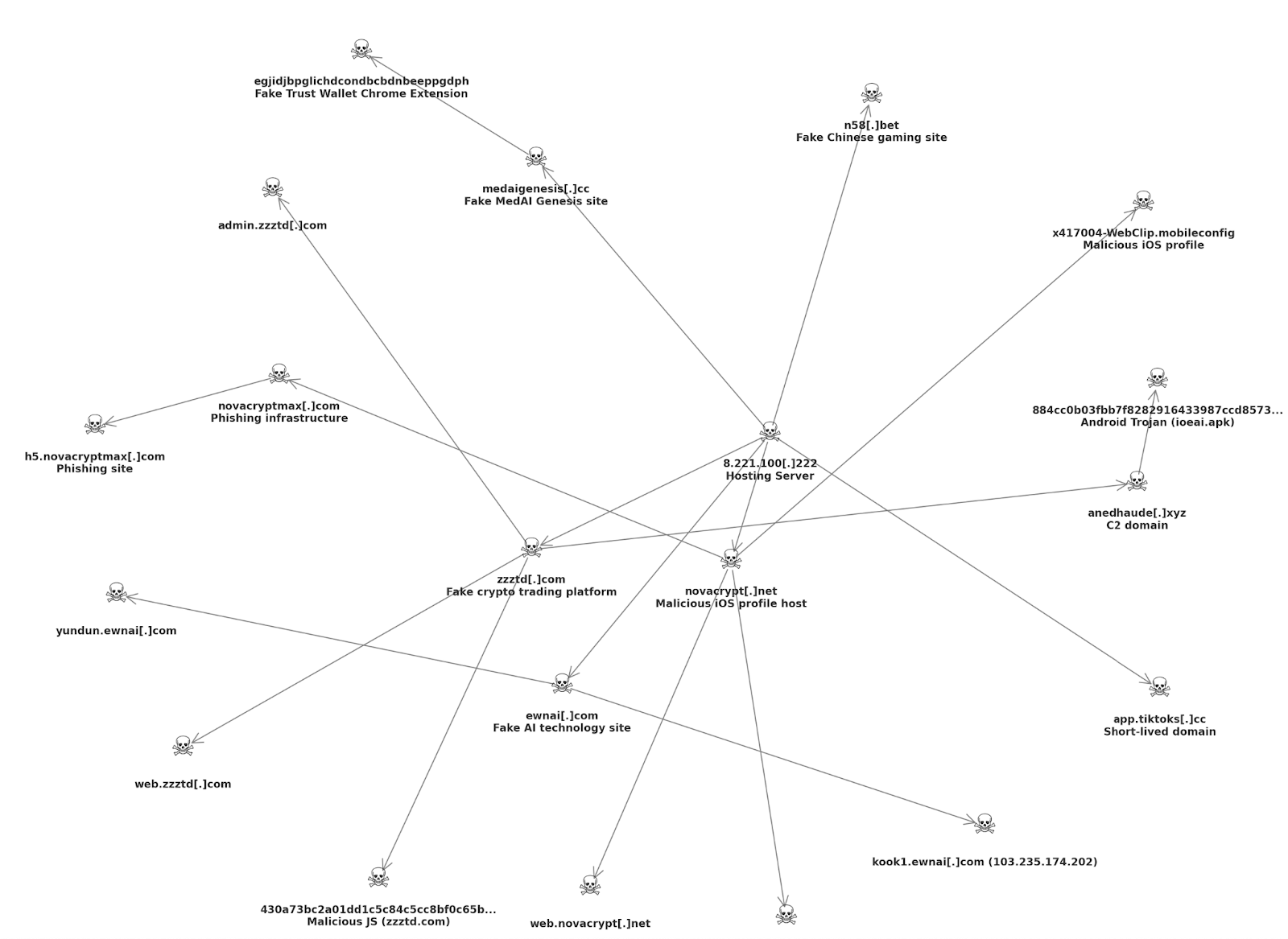

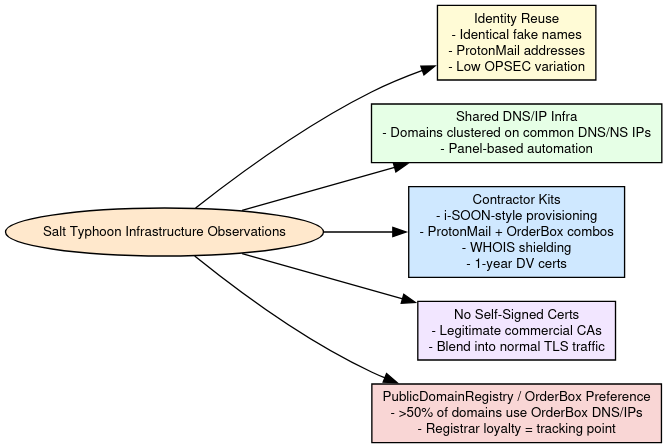

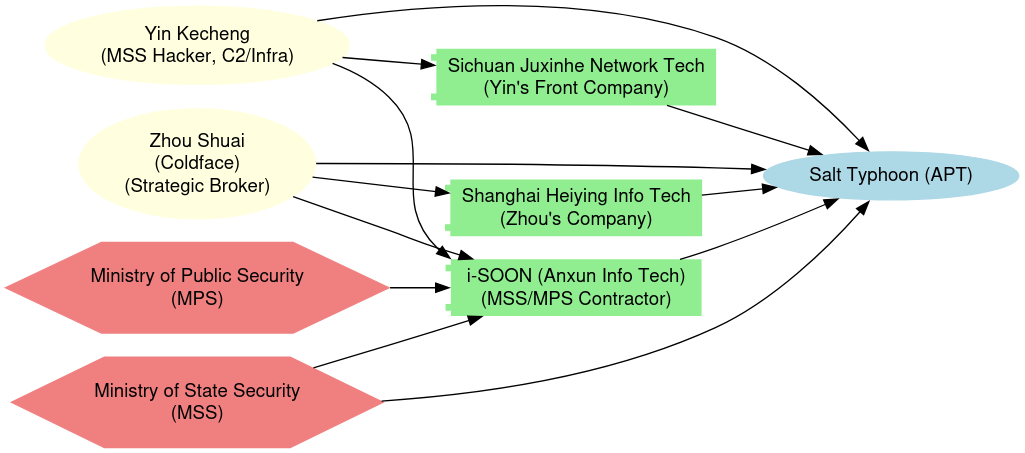

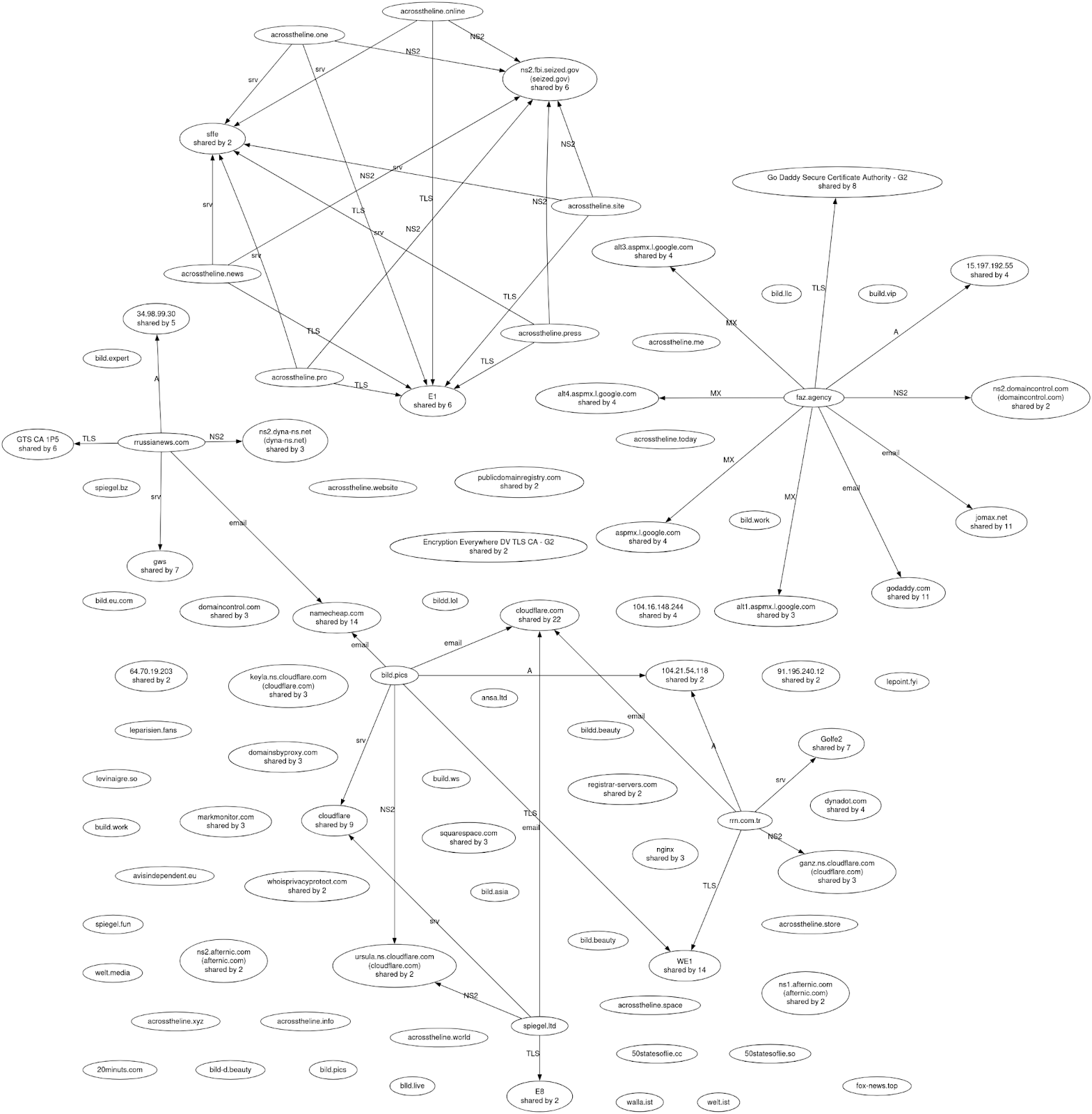

Hosting & IP Space Analysis

Infrastructure analysis reveals a consistent architectural pattern built around layered hosting abstraction. At the outermost layer, domains are fronted by Cloudflare, which provides edge delivery, caching, and origin masking. This CDN fronting obscures backend IP exposure and complicates direct attribution through simple DNS resolution. Behind this edge layer, backend services are deployed across hyperscale cloud providers, principally Google Cloud, where individual sites resolve to distributed virtual instances. At the application layer, disposable WordPress nodes function as the publishing engine, allowing rapid content deployment and replacement without persistent infrastructure commitments.

The dataset supports this model. Across 48 domains, 34 unique IP addresses were observed, indicating distributed backend allocation rather than centralized hosting. A substantial portion of domains resolved through Cloudflare address space in the 104.x range, reinforcing the prevalence of CDN masking. Backend nodes and functions appeared in Google Cloud 34.x ranges as well as some lesser activity in AWS 15.x ranges, often in small micro-clusters of related domains sharing hyperscaler infrastructure or repurposing static assets or content from legitimate websites. A minor presence of European hosting providers exists, but without concentration sufficient to suggest geographic anchoring.

This configuration reflects a cloud-native deployment strategy optimized for flexibility and resilience. Hyperscaler infrastructure provides rapid provisioning, geographic neutrality, and scalable bandwidth, while CDN masking reduces visibility into origin servers. The distributed IP footprint and lack of single-ASN concentration further enhance survivability and reduce detection risk.

Notably, there is no observable concentration of infrastructure within Russian autonomous systems. This absence should not be interpreted as contradictory to Russian-aligned tradecraft. On the contrary, reliance on Western hyperscalers and CDN masking aligns with evolved attribution-resistant design principles. By operating within globally reputable cloud ecosystems, the campaign blends into high-volume commercial traffic, leveraging legitimate infrastructure to reduce investigative friction.

The resulting hosting posture is deliberately attribution-resistant. It prioritizes redundancy, geographic neutrality, and rapid redeployment capacity over static hosting stability. This design is consistent with a professionally managed influence operation engineered for persistence under enforcement pressure rather than a transient spoofing campaign.

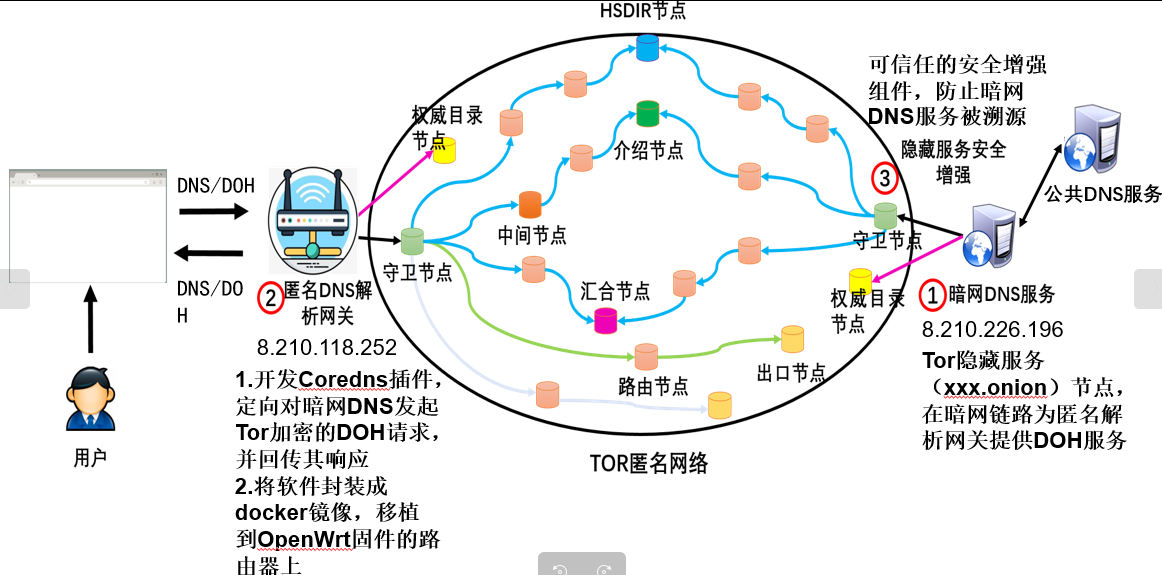

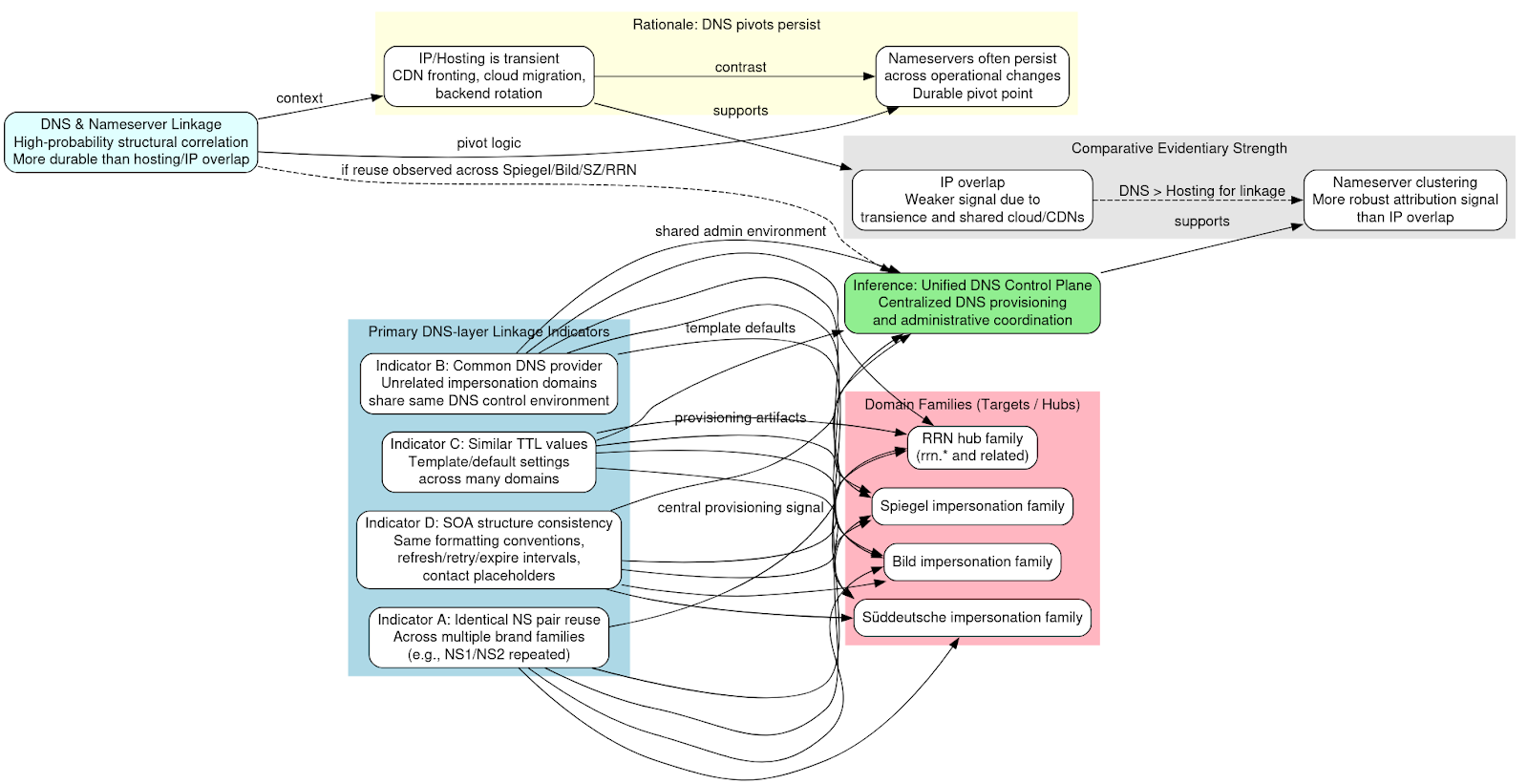

DNS & Nameserver Linkage

DNS-layer analysis provides several high-probability linkage indicators that may offer stronger structural correlation than hosting data alone. While IP addresses can shift due to CDN fronting or cloud migration, nameserver configurations often persist across operational changes and therefore provide a more durable pivot.

One primary indicator would be the reuse of identical nameserver pairs across multiple brand families. If domains impersonating unrelated outlets such as Spiegel, Bild, and Süddeutsche share the same NS records, the likelihood of independent registration diminishes substantially. Shared nameserver infrastructure across distinct media brands would suggest centralized DNS provisioning rather than coincidental overlap.

A related signal would be reliance on the same DNS provider across otherwise unrelated impersonation domains. When domains targeting different national audiences or brands resolve through a common DNS control environment, it implies coordination at the administrative level. Similar time-to-live (TTL) values across domains can further reinforce this signal, as TTL configurations often reflect default settings applied at the account or template level rather than individually tuned parameters.

Consistency in Start of Authority (SOA) structure such as identical formatting conventions, refresh intervals, or authoritative contact placeholders would provide additional evidence of centralized DNS management. SOA artifacts are rarely manipulated for cosmetic purposes and often reveal provisioning templates used by operators.

If nameserver reuse were observed across the Spiegel, Bild, Süddeutsche, and RRN domain families, it would strongly indicate a unified DNS control plane underpinning both narrative hubs and impersonation properties. Such convergence would demonstrate that, despite registrar dispersion and TLD diversification, domain resolution remains orchestrated from a common administrative layer.

In comparative evidentiary strength, nameserver clustering is likely a more robust attribution signal than IP overlap. IP infrastructure can be transient, especially in cloud-native deployments. Nameserver configurations, by contrast, frequently reflect centralized provisioning logic and are less susceptible to routine backend rotation. As a result, DNS-layer commonality may provide the clearest structural linkage within a distributed, attribution-resistant hosting environment.

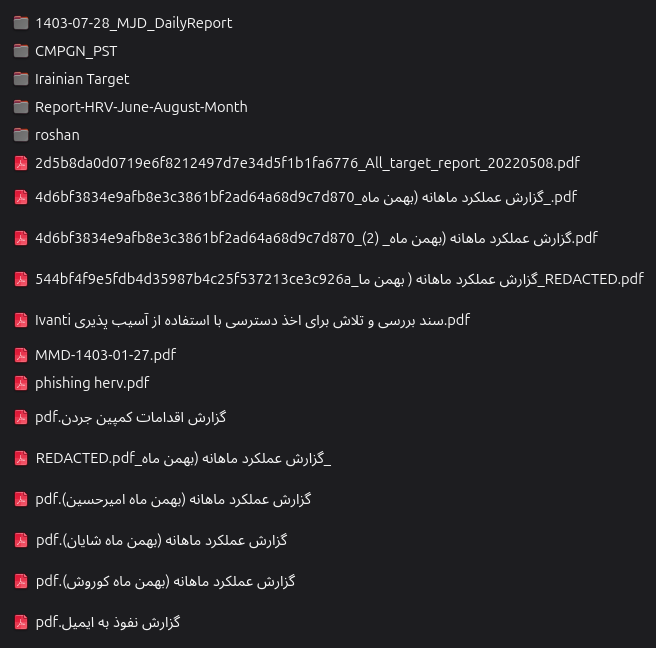

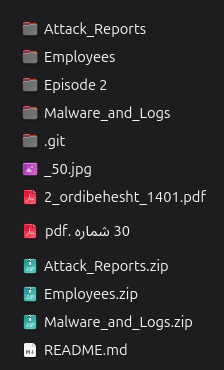

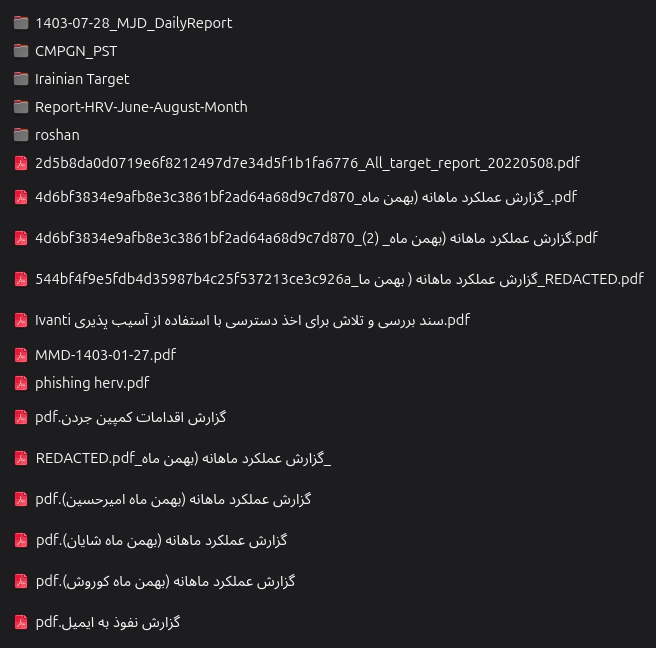

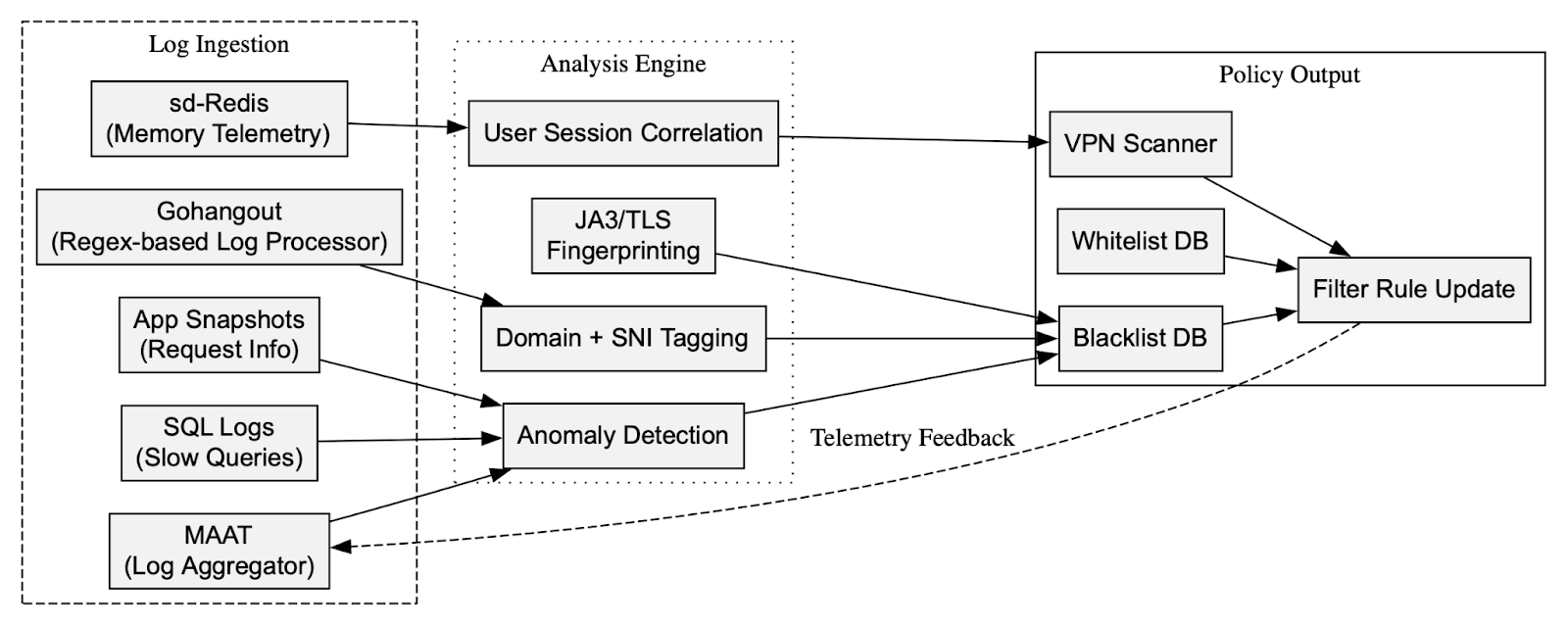

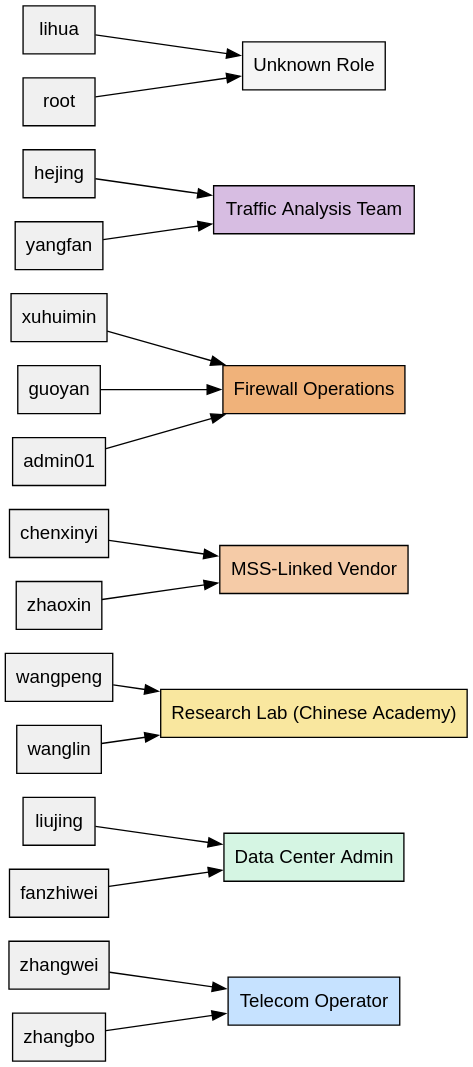

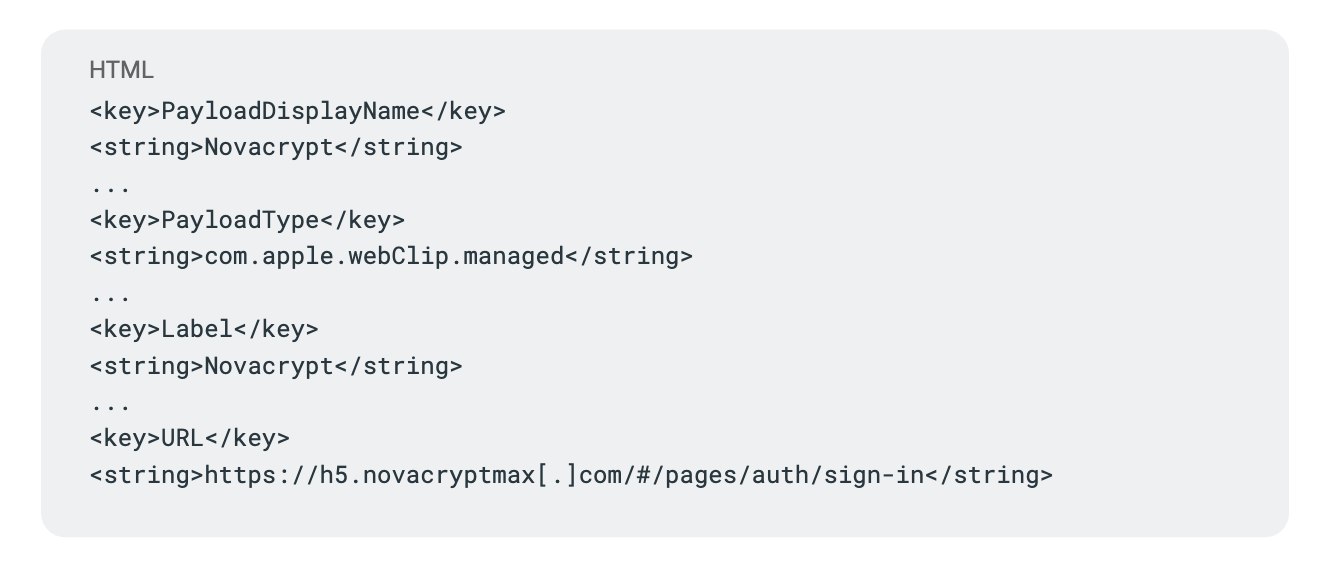

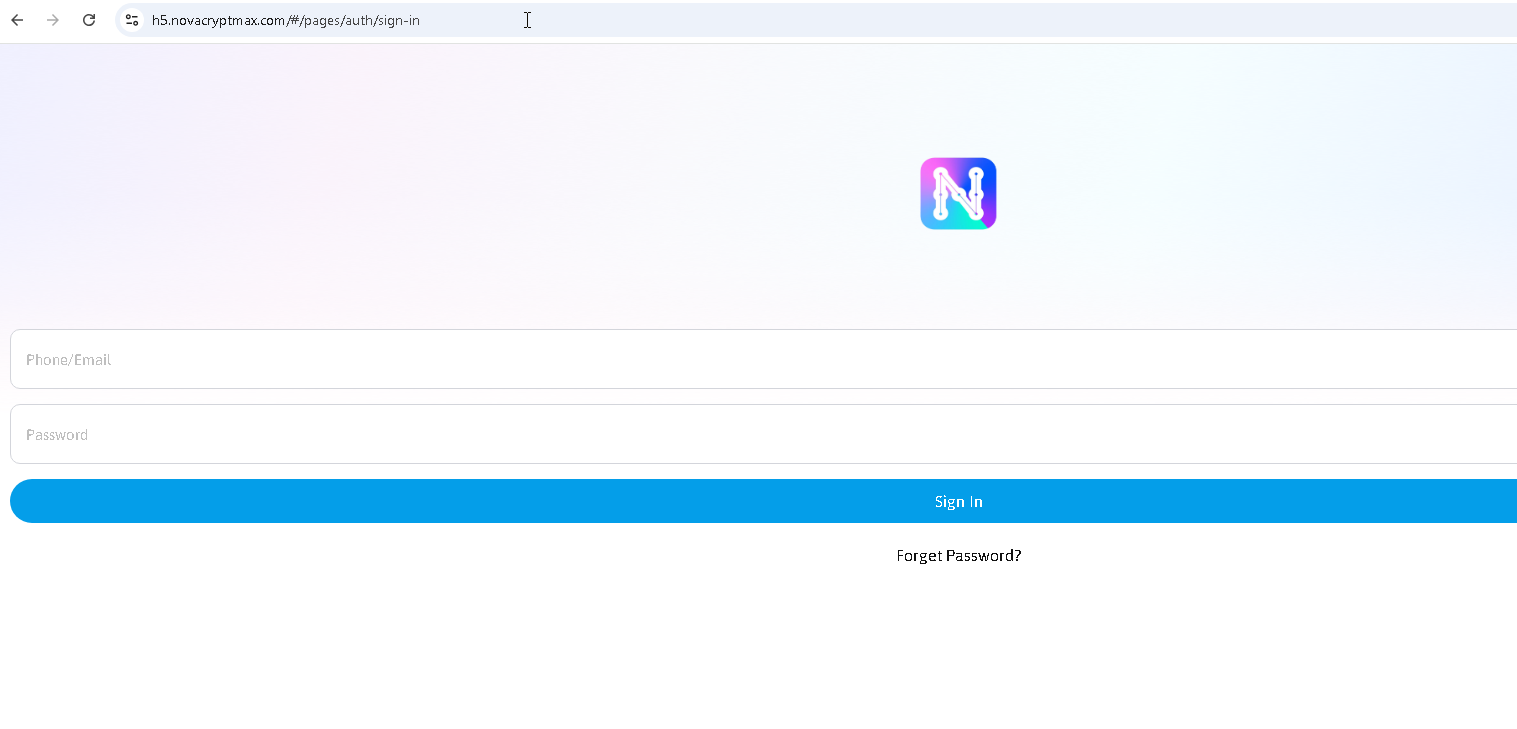

Backend CMS Artifact Analysis

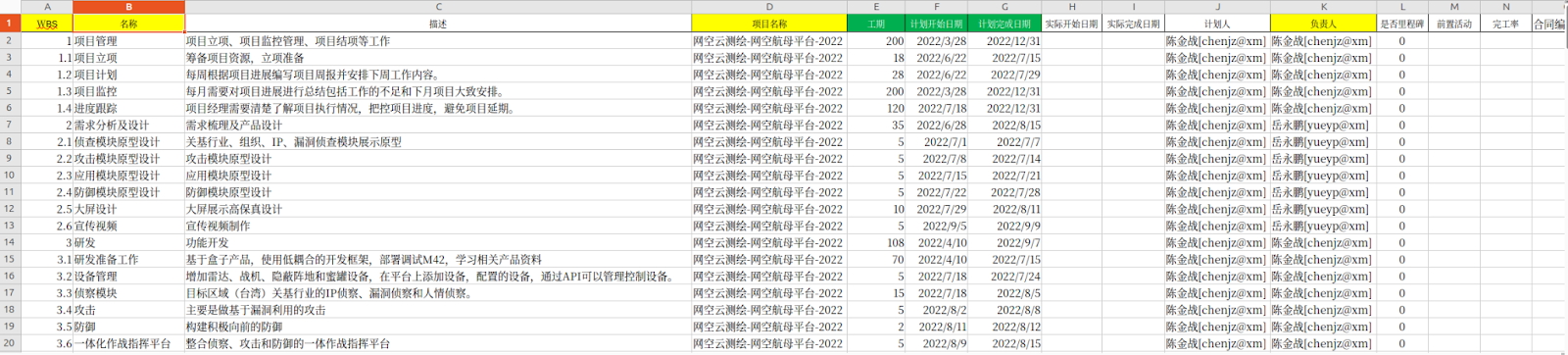

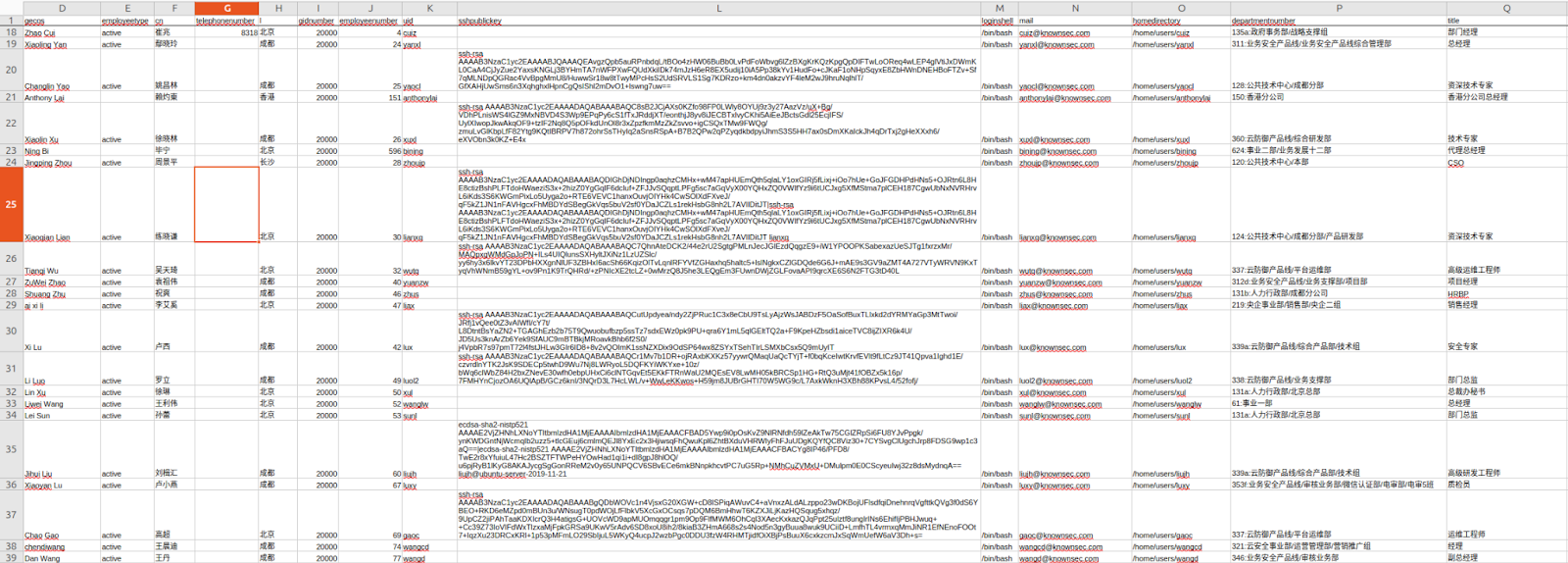

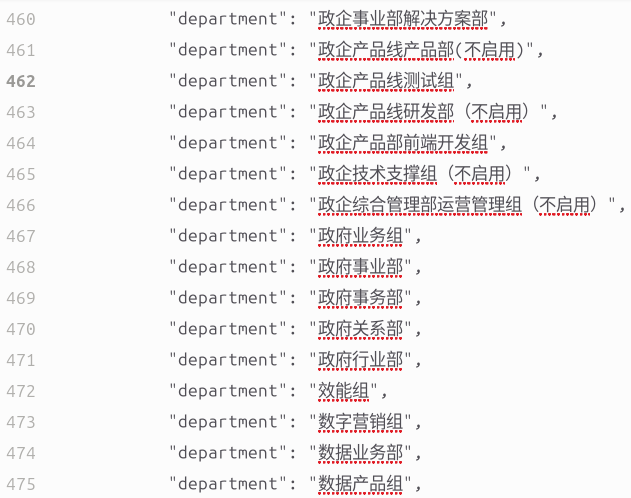

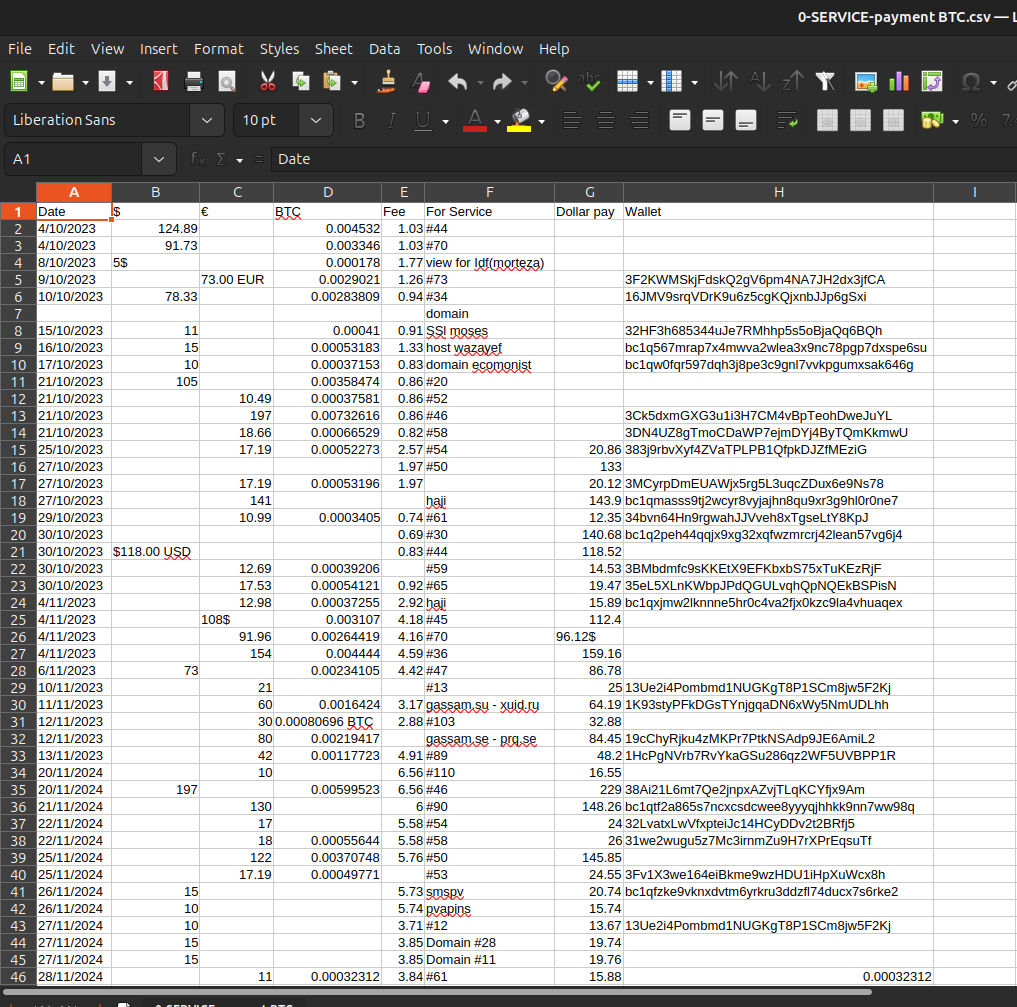

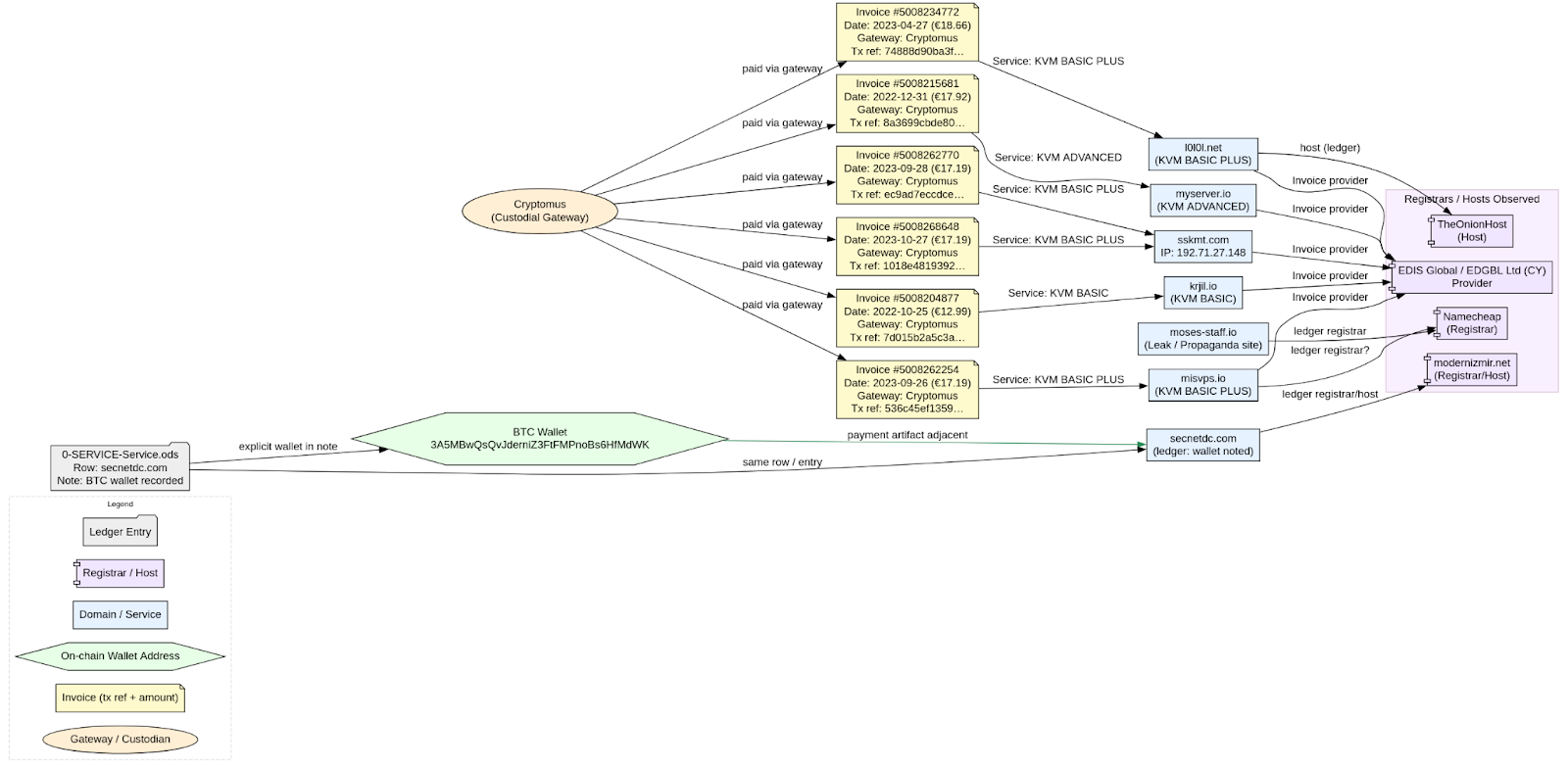

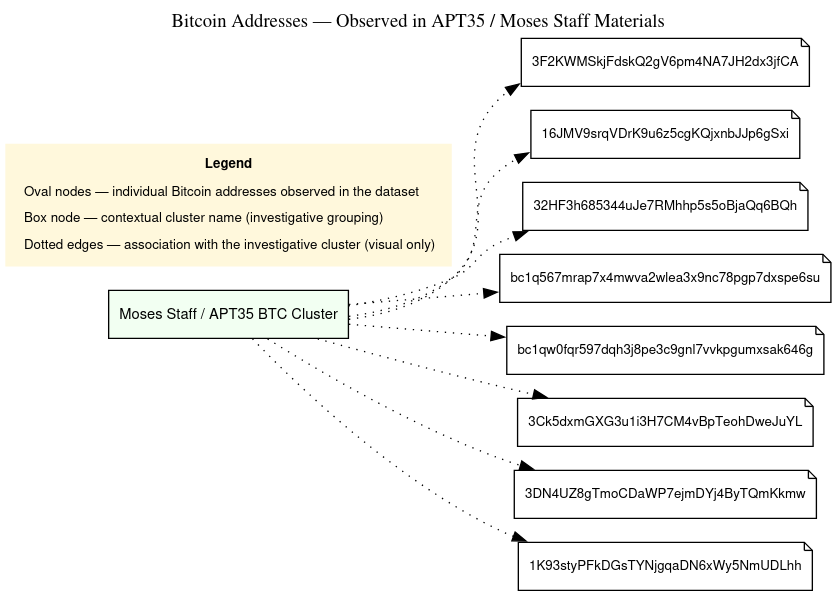

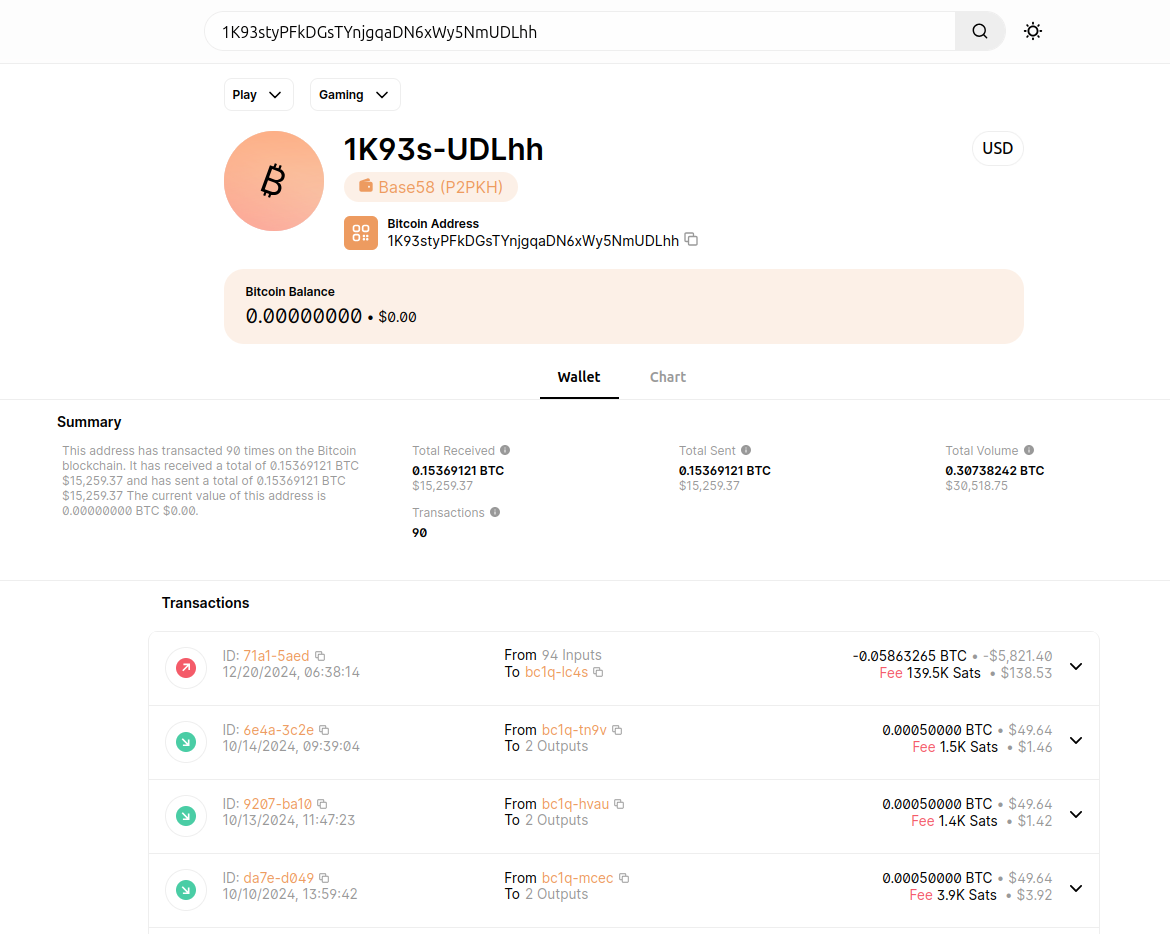

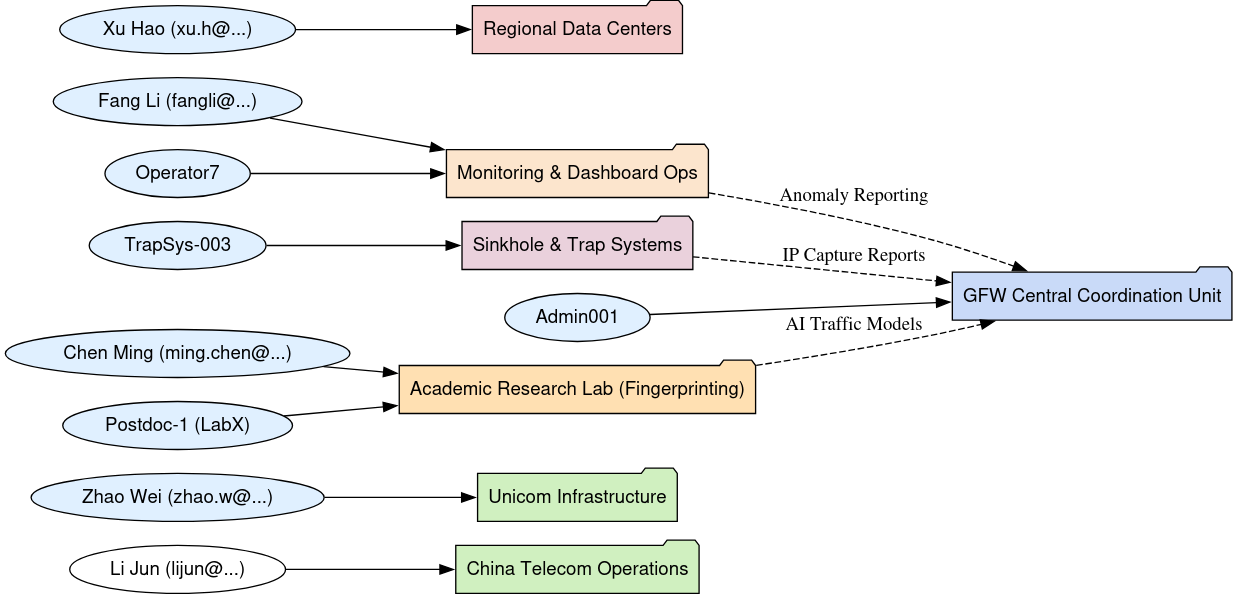

Forensic review of recovered WordPress artifacts provides insight into backend governance and operational discipline. The earliest observable provisioning activity indicates bootstrap configuration using a Yandex-linked email account, suggesting centralized initial setup rather than distributed contributor onboarding. Following this bootstrap phase, multiple accounts associated with the @rrn[.]com[.]tr namespace were rapidly provisioned, reflecting coordinated account creation within a defined administrative domain.

User roles within the CMS exhibit structured segmentation. Accounts labeled with function-specific identifiers such as “seoadmin” and “RRN_Staff” indicate differentiated permissions and workflow responsibilities. This separation of duties is characteristic of managed editorial environments rather than informal publishing collectives. The presence of search-engine-optimization–focused accounts further demonstrates that visibility engineering was embedded into backend operations, not treated as an afterthought.

Artifacts dated to 2025 reveal application-password configurations, which are typically associated with API integrations, automated publishing pipelines, or credential compartmentalization for security control. The continued presence of such artifacts indicates ongoing maintenance and lifecycle management rather than abandonment of infrastructure following enforcement pressure.

Collectively, these backend signals imply centralized coordination of publishing workflows, structured SEO integration, and sustained operational oversight. The pattern reflects a professionalized content management hierarchy with defined roles, controlled credential distribution, and repeatable provisioning logic. Such characteristics are inconsistent with decentralized volunteer activism or loosely organized advocacy networks. Instead, they align with a managed, institutionally structured information operation.

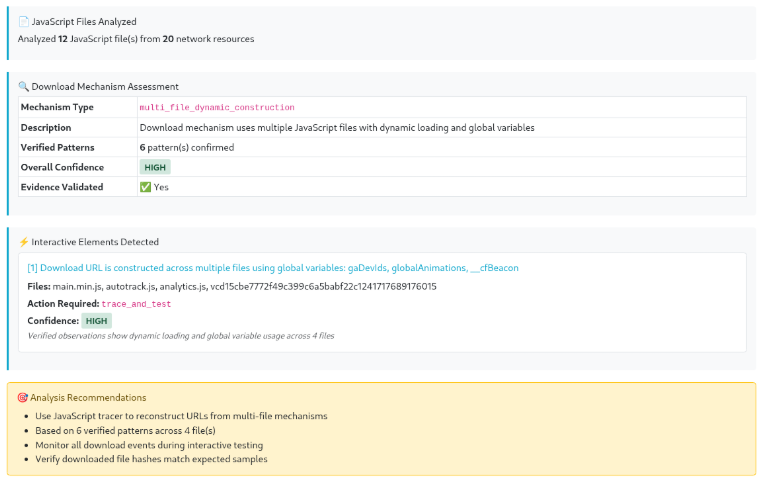

Automated Domain Generation Model

Domain naming patterns across the ecosystem reveal consistent construction logic indicative of automation rather than manual registration. The observed formats follow repeatable templates. The most straightforward pattern replicates the core brand token directly as a second-level domain paired with an alternate top-level extension. A second pattern appends semantic qualifiers to the brand, often news-oriented or temporal terms before applying a conventional TLD. A third variation incorporates geographic modifiers, creating localized variants that maintain brand recognition while implying regional relevance. Additional structures involve typographical manipulation of the brand token itself or preservation of the second-level domain during TLD migration events.

Typographical techniques follow predictable methods. Letter duplication produces visually plausible variants such as “bildd.” Letter omission removes characters to create near-identical strings, for example “blld.” Phonetic substitution alters spelling while retaining recognizability, as in “build.” Semantic suffixes such as “-today,” “-live,” or “-life” introduce news-related framing, while geographic modifiers like “-eu” or “-asia” imply localized legitimacy. These manipulations are systematic and repeat across multiple brand families, reinforcing the likelihood of template-based domain generation.

The preservation of the second-level domain across new TLDs during enforcement events further supports the presence of structured provisioning logic. Rather than improvising new names, operators maintain core tokens and rotate extensions, suggesting preplanned substitution pathways embedded within the registration pipeline.

The consistency and recurrence of these patterns strongly suggest a scripted bulk provisioning mechanism. Domain creation appears to follow predefined logic trees, enabling rapid generation of multiple variants per target brand. This automation facilitates scalability, redundancy, and rapid replacement following seizure or suspension.

Based on the observed logic, predictive domain templates can be modeled. Likely future variants would include constructions such as brand paired with “.media,” “.agency,” or “.today.” Hyphenated semantic extensions appended to established brands such as brand-live or brand-life are also probable. Additionally, migration to lower-scrutiny country-code or generic TLDs such as “.cc” or “.so” remains consistent with prior behavior.

Monitoring Certificate Transparency logs against these structured templates is recommended as an early-warning mechanism. Because automated pipelines often generate certificates shortly after registration, template-based CT monitoring may identify new impersonation domains before large-scale amplification occurs.

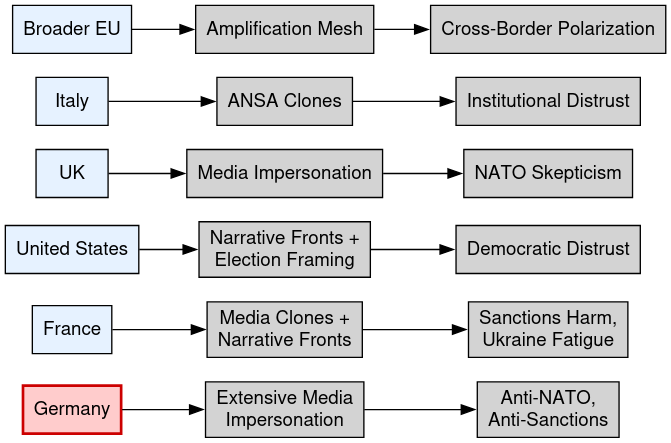

Geographic Target Segmentation

Geographic segmentation within the ecosystem reflects deliberate alignment between infrastructure deployment and narrative emphasis. Targeting is not uniform across regions; instead, infrastructure tactics and messaging themes are calibrated to local political contexts and audience sensitivities.

Germany emerges as the most extensively targeted environment. The infrastructure footprint there is dominated by high-volume media impersonation, particularly of prominent national outlets. The corresponding narrative focus centers on anti-NATO themes, criticism of sanctions policy, and efforts to widen domestic political divisions. The scale and density of impersonation domains associated with German brands indicate prioritization beyond incidental inclusion.

In France, the operational model blends media clones with narrative front domains. Messaging frequently emphasizes the economic costs of sanctions and promotes themes of Ukraine-related fatigue. The infrastructure suggests a strategy aimed at reframing policy debates through domestically contextualized narratives rather than direct geopolitical confrontation.

The United States is approached through narrative front properties combined with election-cycle framing. Rather than relying exclusively on high-fidelity impersonation of national outlets, the ecosystem leverages independently branded sites to question institutional legitimacy and amplify distrust in democratic processes. Timing of domain provisioning aligns with electoral periods, reinforcing the assessment of politically sensitive targeting.

In the United Kingdom, media impersonation remains the dominant tactic. Messaging themes concentrate on skepticism toward NATO policy and criticism of foreign engagement. The structure parallels the German model but appears narrower in scope.

Italy is targeted primarily through impersonation of ANSA and related institutional brands. The emphasis shifts toward undermining institutional trust and reinforcing domestic dissatisfaction narratives. This indicates adaptation to national media ecosystems and audience trust structures.

Across the broader European Union, the campaign employs an amplification mesh model. Rather than focusing exclusively on single-country impersonation clusters, domains and social distribution mechanisms propagate narratives across borders, fostering cross-national polarization and reinforcing pan-European fissures.

The relative density of impersonation domains, narrative alignment, and provisioning volume suggests that Germany represents the highest-priority target within the ecosystem. Infrastructure investment and thematic emphasis converge most heavily in that information environment, indicating strategic weighting rather than incidental inclusion.

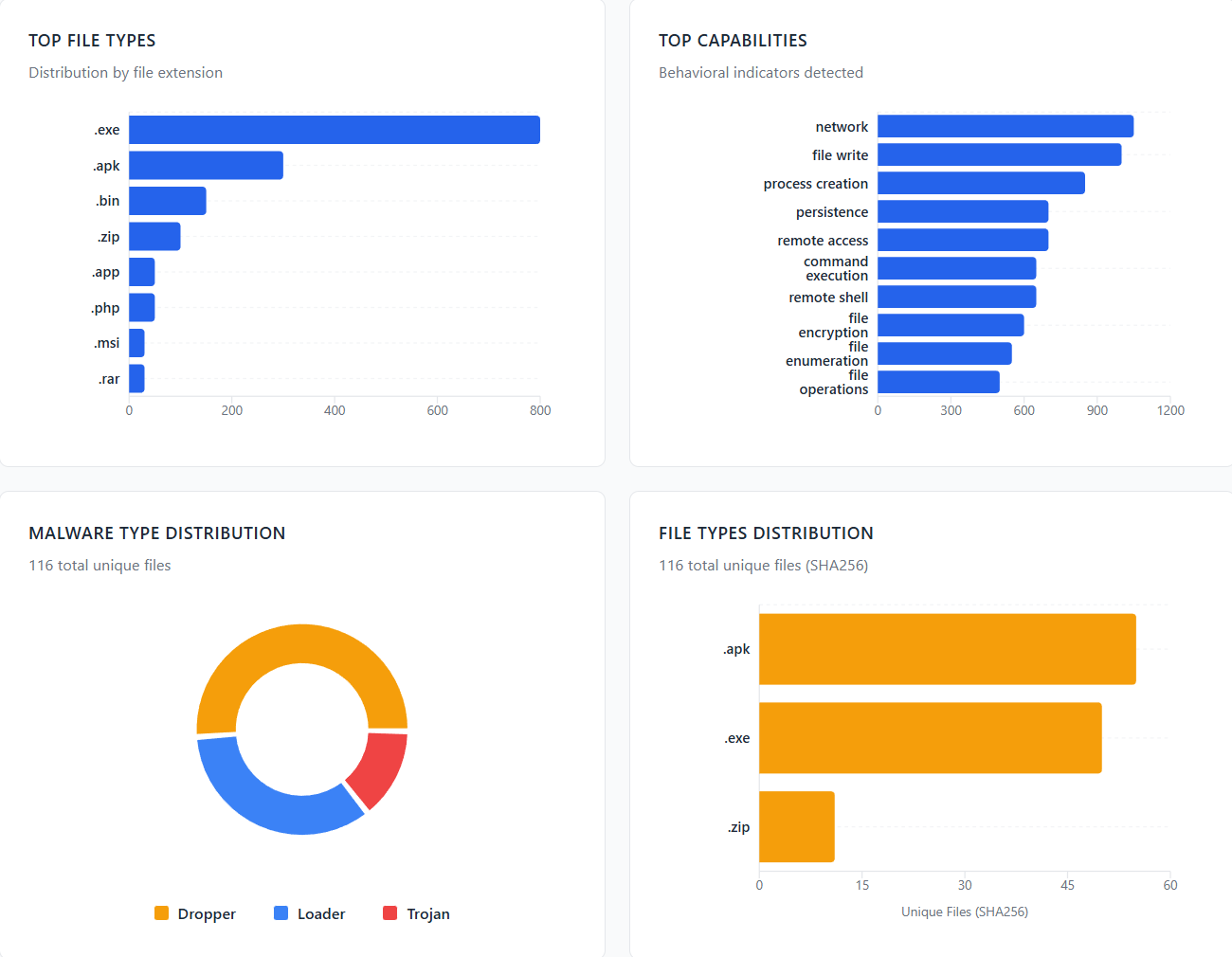

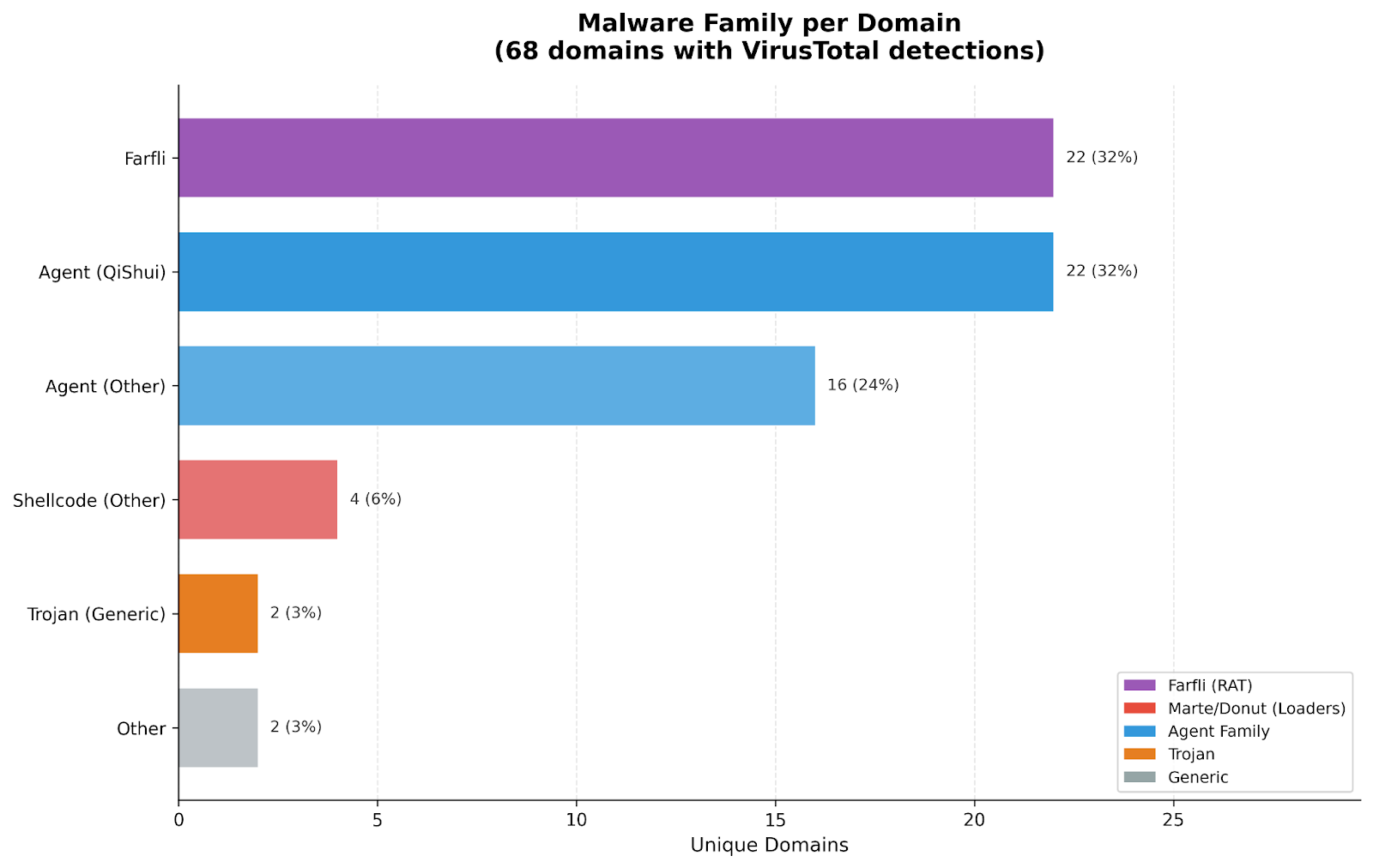

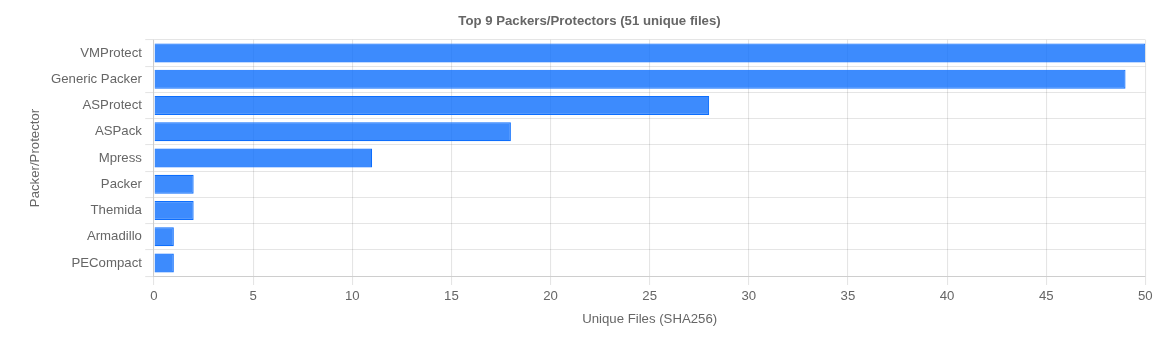

What the Infrastructure Is Not

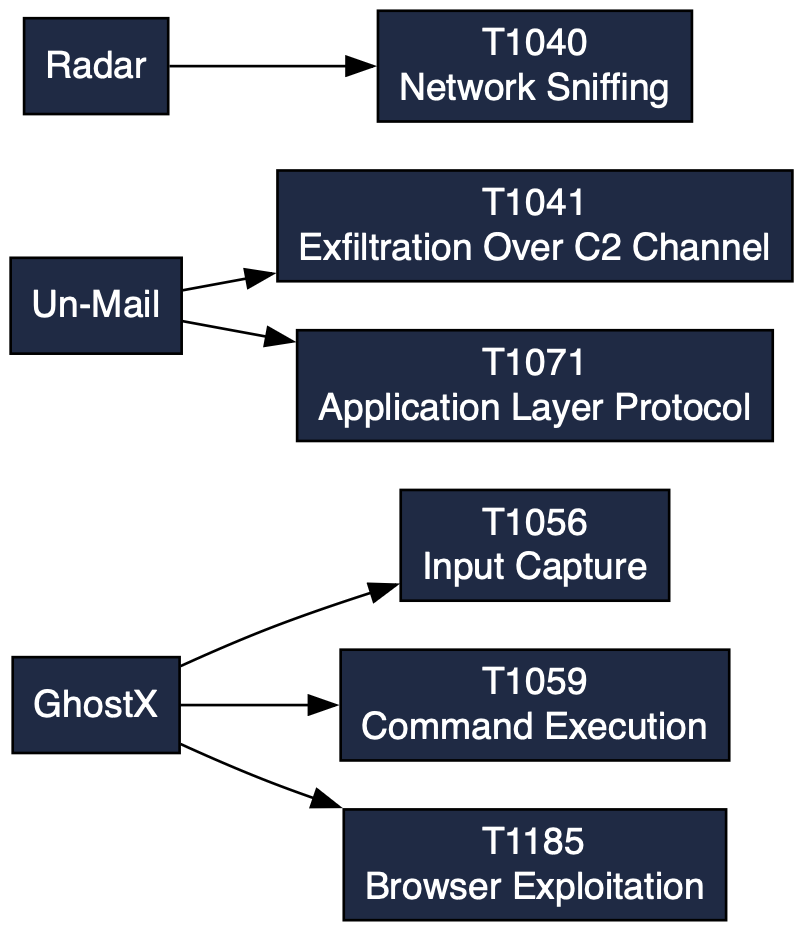

Infrastructure analysis reveals a consistent absence of indicators typically associated with financially motivated cybercrime or intrusion-focused operations. There is no evidence of malware command-and-control coordination embedded within the observed domains. The hosting architecture, DNS behavior, and certificate issuance patterns do not reflect infrastructure designed to manage implants, beacon traffic, or staged payload delivery.

Similarly, there are no artifacts suggesting phishing kit reuse or credential-harvesting frameworks. The domains do not exhibit structural similarities to common phishing templates, nor do they display the rapid redirect logic or form-handling mechanics associated with account compromise campaigns. The absence of credential collection endpoints or kit fingerprint overlap further distinguishes this ecosystem from conventional fraud operations.

There is also no observable affiliate monetization structure. The infrastructure does not show integration with traffic arbitrage networks, affiliate referral programs, or performance-based revenue systems. Domain lifecycles are short and aligned with narrative waves rather than revenue optimization windows. Likewise, there is no evidence of ad network integration, programmatic advertising infrastructure, or content-farming strategies designed to generate advertising impressions at scale.

Hosting patterns further differentiate the operation from typical criminal infrastructure. The ecosystem does not rely on bulletproof hosting providers or obscure offshore ASNs commonly associated with malware distribution or fraud. Instead, it leverages mainstream hyperscaler platforms and CDN fronting, prioritizing camouflage within legitimate cloud ecosystems rather than protection from law enforcement through hardened criminal service providers.

Collectively, these absences are analytically significant. The infrastructure is optimized for narrative dissemination, brand impersonation, and audience influence rather than financial extraction or technical exploitation. Its design reflects an information operation architecture engineered for credibility manipulation and distribution resilience. This is narrative delivery infrastructure, not cybercrime infrastructure.

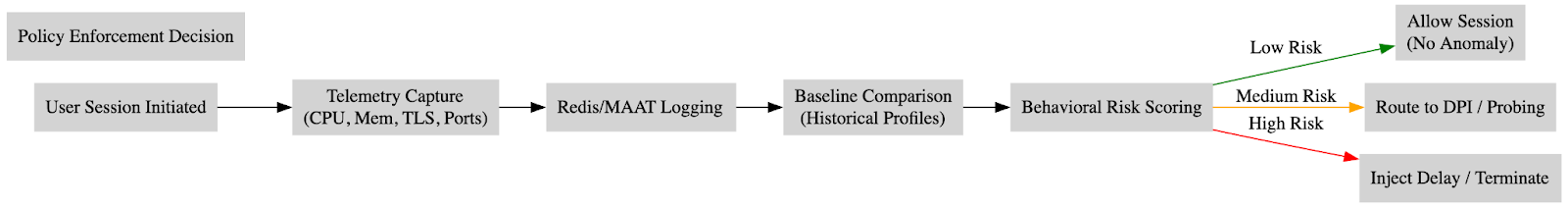

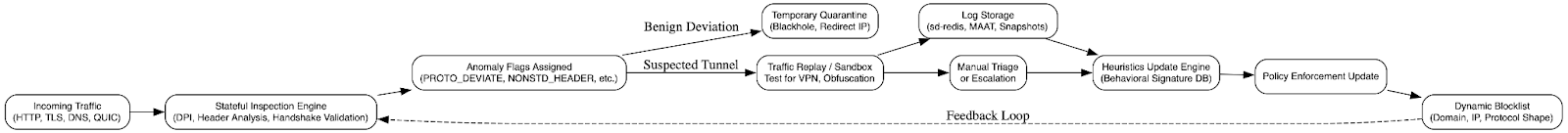

Operational Maturity Assessment

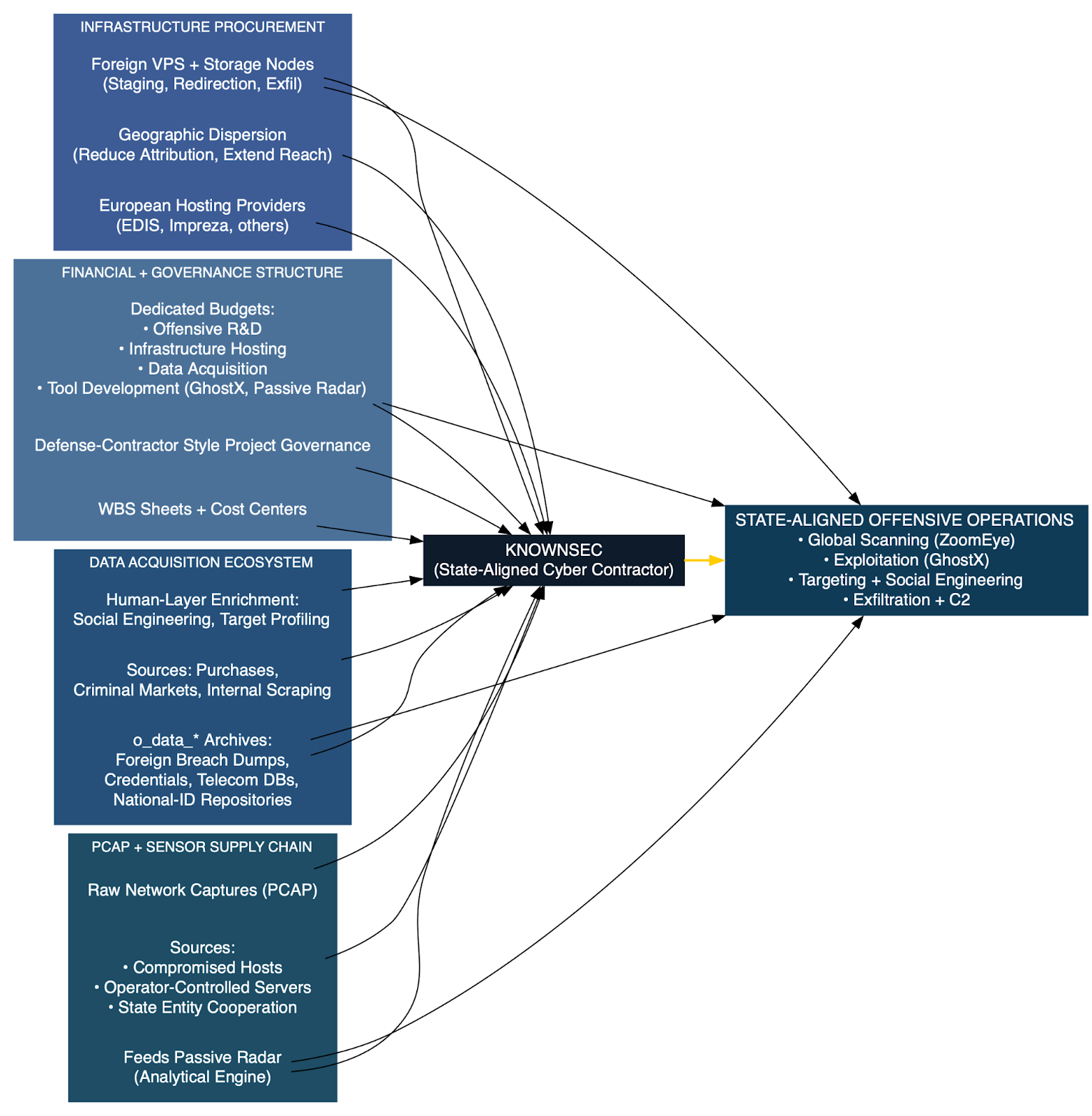

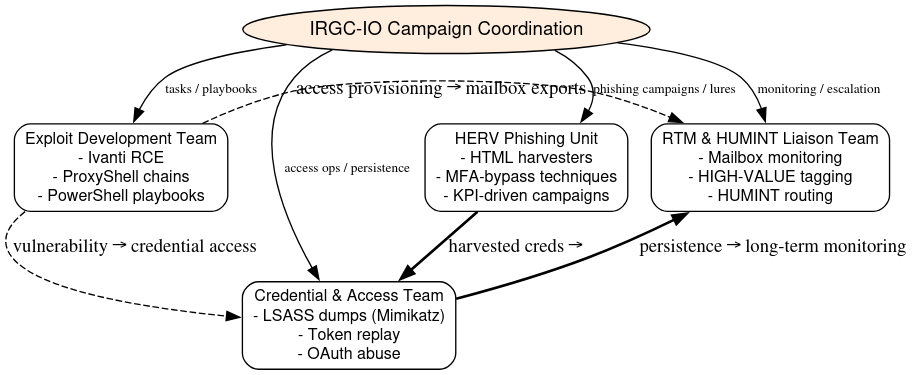

The Doppelgänger ecosystem exhibits operational characteristics consistent with disciplined infrastructure engineering rather than ad hoc domain deployment. Provisioning behavior reflects DevOps-style methodology: domains are registered in coordinated bursts, deployed in structured waves, and integrated into a repeatable pipeline that supports rapid staging and replacement. Infrastructure is treated as code: scalable, replicable, and disposable.

Campaign activation appears synchronized with geopolitical or electoral inflection points, indicating burst staging rather than continuous organic growth. Domains are stockpiled in advance of use, enabling operators to activate replacement nodes with minimal latency following enforcement actions. This pre-positioned redundancy reduces operational downtime and demonstrates forward-planned lifecycle management.

Rapid pivoting in response to seizures further illustrates enforcement-aware design. When domains are disrupted, second-level identifiers are preserved and redeployed under alternate top-level domains. Hosting and DNS configurations are rotated without altering the broader narrative framework. The system absorbs disruption without collapsing, reflecting modular segmentation that isolates functional layers from single points of failure.

The architecture’s reliance on CDN masking, hyperscaler backend infrastructure, and distributed IP allocation demonstrates cloud-native proficiency. Deployment choices prioritize camouflage within legitimate commercial cloud environments, reducing attribution risk and complicating network-level blocking strategies. Infrastructure components are loosely coupled yet centrally coordinated, reinforcing resilience.

Attribution minimization is embedded throughout the lifecycle. Registrar dispersion, privacy shielding, and geographic hosting neutrality collectively reduce direct linkage signals. Operational design favors structural ambiguity while maintaining internal coherence.

The campaign’s evolution reflects increasing sophistication under pressure. During Phase I (2022–2023), the model centered on a relatively centralized RRN hub supported by impersonation spokes. Phase II (2024) introduced enforcement disruption through domain seizures, testing the resilience of the architecture. In Phase III (2024–2025), the ecosystem adapted into a more distributed modular mesh, reducing reliance on singular hubs and expanding TLD diversification.

Rather than diminishing under enforcement pressure, the infrastructure matured. Redundancy increased, segmentation deepened, and migration pathways became more seamless. The trajectory indicates learning and adaptation, reinforcing the assessment that the operation is professionally managed and strategically sustained rather than episodic or opportunistic.

Strategic Assessment

The Doppelgänger ecosystem exhibits characteristics consistent with industrialized influence infrastructure rather than episodic or improvised activity. Its provisioning discipline, redundancy planning, and lifecycle management imply sustained funding and coordinated oversight. The infrastructure is treated as a strategic asset, engineered for persistence under scrutiny and adaptable under enforcement pressure. This reflects a model in which infrastructure is not merely a vehicle for messaging but the foundation of the influence operation itself.

The operational posture aligns with an infrastructure-first influence warfare framework. Domains are provisioned in waves, diversified across TLDs, shielded behind CDN layers, and redeployed with minimal latency following disruption. Backend publishing environments are structured and role-segmented. DNS and hosting choices prioritize camouflage within legitimate hyperscaler ecosystems. These attributes collectively indicate that technical architecture is central to the campaign’s design, not secondary to narrative content.

Psychological operations are embedded within this technical foundation. Messaging is geographically segmented, timed to political cycles, and distributed through impersonation layers engineered to exploit audience trust. The technical and narrative components are integrated rather than siloed. DevOps-style provisioning supports narrative agility, enabling rapid amplification, replacement, or recalibration in response to geopolitical developments.

The campaign represents a hybridization of multiple strategic disciplines. Cyber infrastructure strategy provides resilience, obfuscation, and scalability. Narrative warfare supplies thematic direction and audience targeting. Search ecosystem manipulation ensures discoverability and legitimacy through SEO optimization. Election-cycle timing introduces temporal precision, aligning infrastructure activation with moments of heightened political sensitivity.

Taken together, these characteristics distinguish the operation from opportunistic spoofing or isolated propaganda efforts. The ecosystem reflects structured, enforcement-aware influence engineering. Its design anticipates disruption, incorporates redundancy by default, and integrates technical and psychological components into a cohesive operational model.

Editor’s Note: DomainTools Investigations engaged in pre-publication collaboration with both Google Threat Intelligence Group and Amazon Web Services Threat Intelligence on this material. Both teams were immediately responsive, engaging in analysis in their respective areas and providing helpful feedback. We appreciate their partnership.

Appendix A Domain Data Assessed Map (48 domains)

Appendix B Bibliography

Correctiv. 2024. “Inside Doppelganger: How Russia Uses EU Companies for Its Propaganda.” July 22, 2024. https://correctiv.org/en/fact-checking-en/2024/07/22/inside-doppelganger-how-russia-uses-eu-companies-for-its-propaganda/.

Der Spiegel. 2026. “Im Inneren der russischen Propagandamaschine.”

https://www.spiegel.de/politik/hacktivist-infiltriert-desinformationskampagne-im-inneren-der-russischen-propagandamaschine-a-265fd485-1d0d-45b6-b0b3-4fd46091ddfa.

Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab). 2024a. “How Doppelganger and Other Russia-Linked Operations Target U.S. Elections.” September 6, 2024. https://dfrlab.org/2024/09/06/how-doppelganger-and-other-russia-linked-operations-target-us-elections/.

Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab). 2024b. “Doppelganger Websites Persist One Month Following U.S. Government Seizures.” October 9, 2024. https://dfrlab.org/2024/10/09/doppelganger-websites-persist/.

European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO). 2024. “Doppelganger Investigations Bring Russian Propaganda Campaign to a Halt.” November 18, 2024. https://edmo.eu/publications/doppelganger-correctiv-investigations-bring-russian-propaganda-campaign-to-a-halt/.

European External Action Service (EEAS). 2024. “Doppelganger Strikes Back: Unveiling FIMI Activities Targeting European Parliament Elections.” June 2024. https://euvsdisinfo.eu/doppelganger-strikes-back-unveiling-fimi-activities-targeting-european-parliament-elections/.

EU DisinfoLab and Qurium. 2022. Doppelganger: Media Clones Serving Russian Propaganda. September 27, 2022. https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/semon9-giki0/2022-09-27-EUDisinfoLab-Qurium-Doppelganger.pdf.

European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (ECPMF). 2024. “Actions Must Be Taken to Address Mass Pro-Russian Spoofing of Legitimate Media Outlets.” September 30, 2024. https://www.ecpmf.eu/actions-must-be-taken-to-address-mass-pro-russian-spoofing-of-legitimate-media-outlets/.

Lawfare. 2024. “Making Sense of the Doppelganger Disinformation Operation.” October 16, 2024. https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/lawfare-daily--making-sense-of-the-doppelganger-disinformation-operation--with-thomas-rid.

Rid, Thomas. 2024. “The Lies Russia Tells Itself.” Foreign Affairs, September 30, 2024. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/lies-russia-tells-itself.

STRATCOM COE. 2024. The Doppelganger Case: Assessment of Platform Regulation on the EU Disinformation Environment. https://stratcomcoe.org/publications/the-doppelganger-case-assessment-of-platform-regulation-on-the-eu-disinformation-environment/304.

U.S. Cyber Command. 2024. “Russian Disinformation Campaign ‘DoppelGänger’ Unmasked.” September 3, 2024. https://www.cybercom.mil/Media/News/Article/3895345/russian-disinformation-campaign-doppelgnger-unmasked-a-web-of-deception/.

U.S. Department of Justice. 2024. “Justice Department Disrupts Covert Russian Government-Sponsored Foreign Malign Influence Operation.” September 4, 2024. https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/pr/justice-department-disrupts-covert-russian-government-sponsored-foreign-malign-influence.