Executive Summary

Salt Typhoon is a Chinese state-sponsored cyber threat group aligned with the Ministry of State Security (MSS), specializing in long-term espionage operations targeting global telecommunications infrastructure. Active since at least 2019, Salt Typhoon has demonstrated advanced capabilities in exploiting network edge devices, establishing deep persistence, and harvesting sensitive communications metadata, VoIP configurations, lawful intercept data, and subscriber profiles from telecom providers and adjacent critical infrastructure sectors.

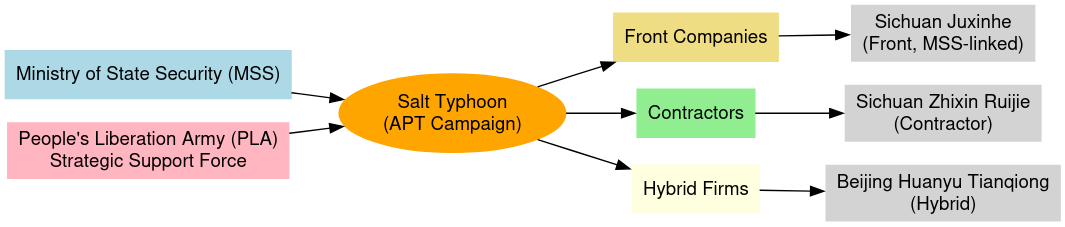

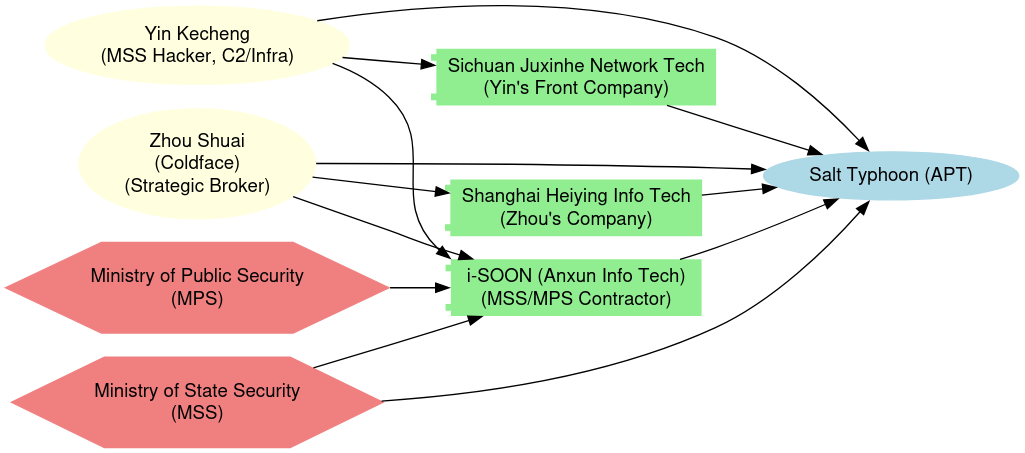

Salt Typhoon operates with both direct MSS oversight and the support of pseudo-private contractor ecosystems, leveraging front companies and state-linked firms to obscure attribution. Recent legal and intelligence reporting confirms that Salt Typhoon maintains operational ties to i-SOON (Anxun Information Technology Co., Ltd.), a prominent MSS contractor known for enabling offensive cyber operations through leased infrastructure, technical support, and domain registration pipelines.

Salt Typhoon’s targeting profile spans the U.S., U.K., Taiwan, and EU, with confirmed breaches in at least a dozen U.S. telecom firms, multiple state National Guard networks, and allied communications providers. Their campaigns utilize bespoke malware, living-off-the-land binaries (LOLBINs), and stealthy router implants, and are notable for their use of publicly trackable domains registered with false U.S. personas, marking a rare lapse in tradecraft among advanced Chinese threat actors.

Background

Salt Typhoon is a state-sponsored advanced persistent threat (APT) group attributed to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and aligned specifically with the Ministry of State Security (MSS). First observed in 2019, the group has become increasingly active and visible through public indictments, technical advisories, and leaked contractor documents—exposing not only its campaigns but also the hybrid contractor-state model behind its operations.

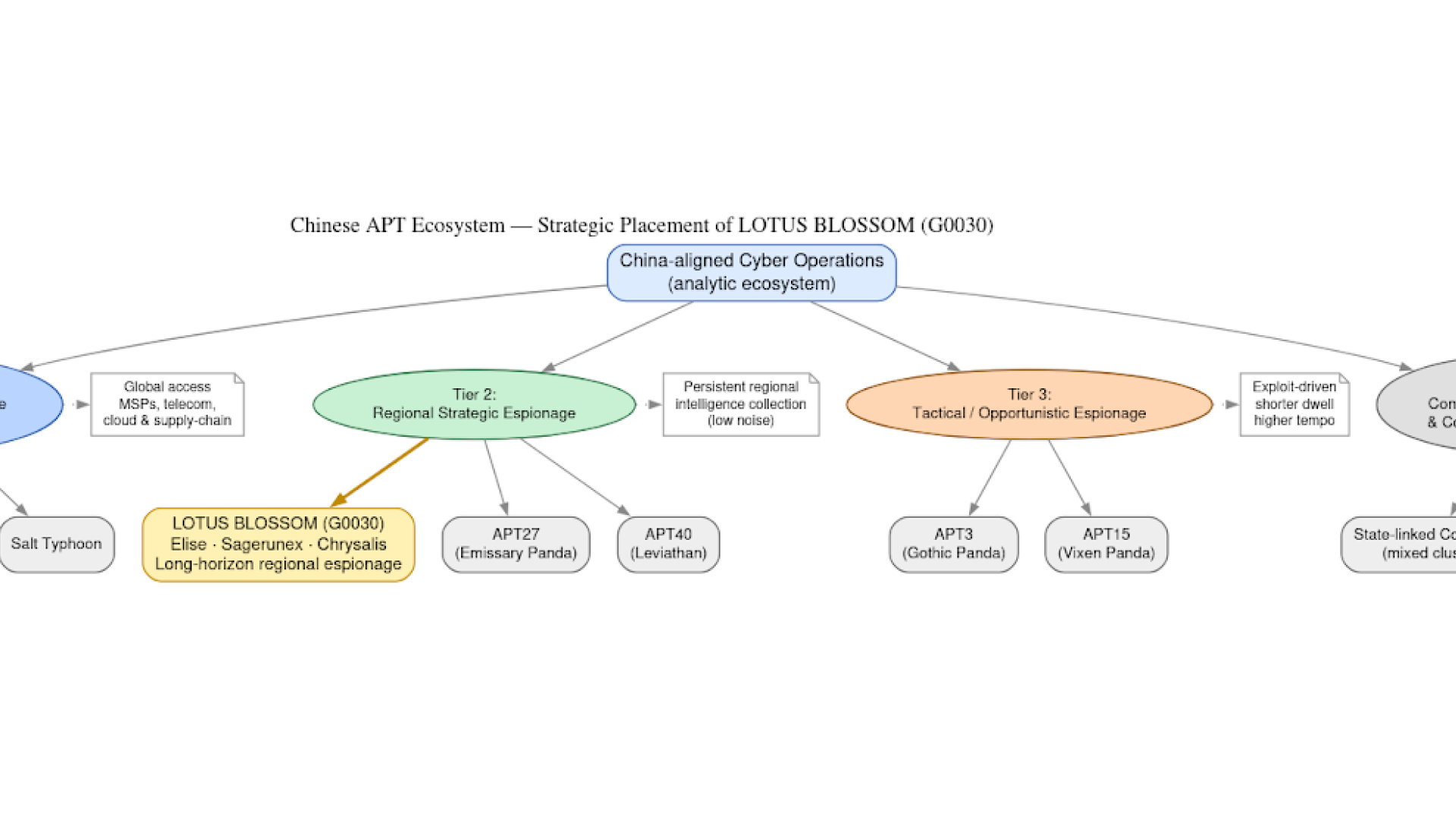

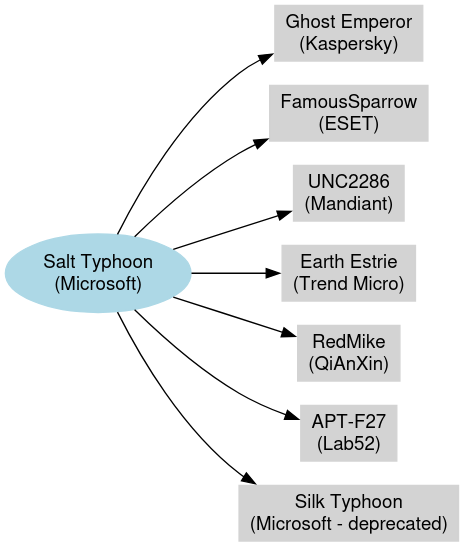

Salt Typhoon is part of a larger naming taxonomy introduced by Microsoft, which classifies Chinese nation-state actors under the “Typhoon” label. It is believed to overlap with or operate in conjunction with previously known clusters such as Ghost Emperor (Kaspersky), FamousSparrow (ESET), Earth Estrie (Trend Micro), and UNC2286 (Mandiant). Some infrastructure and malware characteristics have also shown ties to UNC4841, further blurring attribution boundaries within China’s expansive APT ecosystem.

What distinguishes Salt Typhoon from other PRC-linked actors is its direct targeting of global telecommunications infrastructure for long-term signals intelligence (SIGINT) collection. The group has demonstrated sophisticated tradecraft in:

- Exploiting network edge devices (routers, VPN gateways, firewalls),

- Maintaining long-dwell persistence via firmware/rootkit implants,

- Harvesting lawful intercept data, VoIP configurations, and subscriber metadata from telecom providers,

- And using plausibly deniable contractor infrastructure to obscure attribution.

This report consolidates known intelligence, indictments, IOCs, and operational profiles for Salt Typhoon to support attribution, detection, and threat modeling.

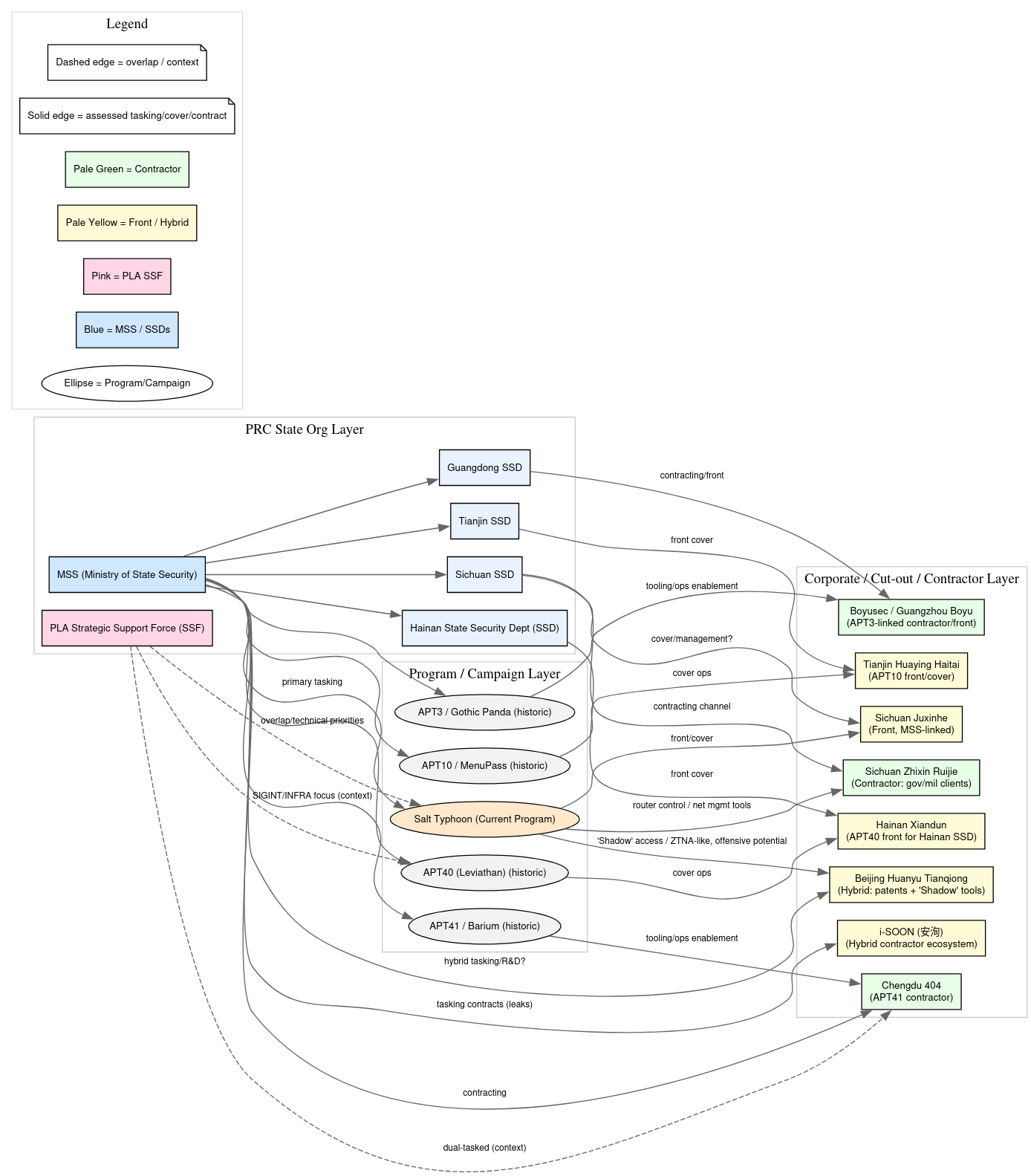

Salt Typhoon within the Chinese Nation-State Cyber Intelligence Structure

Salt Typhoon represents not merely a loose collection of intrusion campaigns, but a state-directed cyber espionage program embedded within the operational apparatus of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Its activity is consistent with the model observed across other PRC “Typhoon” actors: centralized tasking from the Ministry of State Security (MSS), supplemented by the use of contractor and front-company ecosystems that provide scalable infrastructure, tooling, and deniability. The group’s consistent focus on U.S. telecommunications providers, defense-adjacent networks, and allied critical infrastructure sectors is aligned with MSS priorities of foreign intelligence collection, counterintelligence support, and preparation of the battle space.

Although the MSS remains the primary beneficiary of Salt Typhoon operations, technical overlaps with missions traditionally associated with the People’s Liberation Army Strategic Support Force (PLA SSF) suggest that elements of the PLA’s mandate, particularly communications exploitation, SIGINT, and critical infrastructure disruption planning—are also served by this program. By embedding implants in routers, VPN gateways, and telecom backbone equipment, Salt Typhoon delivers persistent access not only for espionage but also for long-term contingency operations, ensuring that PRC intelligence and military planners can monitor, disrupt, or degrade communications infrastructure if required during geopolitical crises. In this sense, Salt Typhoon should be understood as a dual-use capability: a cyberespionage engine serving day-to-day intelligence needs while simultaneously providing the technical foundation for potential wartime cyber operations.

MSS and PLA Roles

Ministry of State Security (MSS):

- The MSS is the primary civilian intelligence service responsible for foreign intelligence, counterintelligence, and cyber-enabled espionage.

- Salt Typhoon shows operational hallmarks of MSS regional bureaus, particularly the Chengdu presence, leveraging local contractors and front companies.

- Firms like Sichuan Juxinhe and Beijing Huanyu Tianqiong are assessed to be either fronts or semi-integrated subsidiaries, mirroring MSS’s historical practice of using corporate cut-outs.

People’s Liberation Army (PLA):

- PLA units (particularly under the Strategic Support Force) have historically targeted communications infrastructure for SIGINT and C4ISR disruption.

- While PLA attribution to Salt Typhoon is less direct, the targeting of backbone and edge routers suggests technical overlap with PLA’s mandate to prepare battlefields in cyberspace.

- Contractors such as Sichuan Zhixin Ruijie may provide dual-use capabilities for both MSS espionage and PLA operational readiness.

Chinese Corporate Hacking Support Infrastructure

The recent joint cybersecurity advisory (August 2025) shed light on three Chinese companies implicated in supporting the operations of Salt Typhoon: Sichuan Juxinhe Network Technology (四川聚信和), Beijing Huanyu Tianqiong Information Technology (北京寰宇天穹), and Sichuan Zhixin Ruijie Network Technology (四川智信锐捷). Each entity demonstrates a different operational model: front companies serving as covers for MSS-linked divisions, and contractors providing technical products and services with both defensive and offensive applications. This model aligns closely with previously documented ecosystems, such as the exposure of i-SOON (安洵科技), where corporate structures serve dual purposes as commercial entities and enablers of state espionage campaigns.

Salt Typhoon-Linked Firms

Sichuan Juxinhe Network Technology

- Likely MSS front company, minimal legitimate business presence.

- Unusual element: 15 software copyrights possibly registered on behalf of an MSS division.

- Fits classic indicators of a cut-out entity used to mask state cyber operations.

Beijing Huanyu Tianqiong Information Technology

- Founded in 2021, coinciding with early Salt Typhoon activity.

- Operates a Zero Trust Defense Lab, offering both legitimate security services (penetration testing, IR) and products with potential C2 and covert access functions (e.g., Shadow Network).

- Evidence suggests hybrid role: front company characteristics with some self-sustaining innovation, patents, and recruitment efforts.

- Proximity to Sichuan Zhixin Ruijie’s Chengdu office suggests co-location strategy for operational synergy.

Sichuan Zhixin Ruijie Network Technology

- Established 2018, later certified as a high-tech SME and contractor for government/military clients.

- Products such as router control systems and network traffic monitoring platforms possess clear offensive potential.

- Functions as a legitimate contractor rather than a pure front, demonstrating how PRC state cyber programs leverage existing commercial capacity for deniable operations.

Parallels and Overlaps with i-SOON

The Salt Typhoon corporate ecosystem echoes the i-SOON leaks (2024), which revealed:

- Direct contracting relationships between Chinese intelligence services (MSS, PLA) and nominally private cybersecurity companies.

- Use of hybrid companies mixing legitimate commercial activities with covert offensive cyber tasks.

- Shared personnel pools, with employees oscillating between state agencies, private firms, and academic research labs.

Like i-SOON, Salt Typhoon’s supporting companies illustrate how the PRC cyber apparatus blurs the lines between state, semi-private, and private entities. Both ecosystems leverage:

- Front companies (minimal digital presence, few employees, registered IP) to obscure attribution.

- Legitimate contractors (with patents, certifications, government clients) to provide scalable, high-quality tools and services.

- Innovation-driven hybrids, balancing R&D, patents, and proprietary software development with covert tasking.

Front Company Infrastructure

Multiple companies have been sanctioned or named as enablers in Salt Typhoon’s tradecraft, including:

- Sichuan Juxinhe Network Technology Co., Ltd.: Tied to Yin Kecheng; facilitated domain control, server management, and malware staging.

- Shanghai Heiying Information Technology Co., Ltd.: Tied to Zhou Shuai; enabled data laundering and resale of stolen network access.

These entities provided infrastructure, logistics, and plausible deniability, allowing MSS operators to mask espionage as commercial or third-party actions.

Ties to i-SOON: China’s Hacker-for-Hire Engine

i-SOON (Anxun Information Technology Co., Ltd.) is a Chinese cyber contractor linked to both the Ministry of State Security (MSS) and Ministry of Public Security (MPS). The company gained international attention following a 2024 GitHub data leak that exposed internal documents, tools, and tasking relationships with state clients.

i-SOON operates as a pseudo-private offensive cyber firm, bridging the gap between state priorities and a scalable, deniable contractor ecosystem. Their services include:

- Custom malware and implant development

- Infrastructure registration (e.g., domains, cloud servers)

- Threat actor support tooling (e.g., internal C2 kits)

- OSINT scraping and target profiling modules

Confirmed Connections to Salt Typhoon

Significance of i-SOON Ties

- Operational Deniability: Salt Typhoon’s use of i-SOON demonstrates how the MSS leverages contractor cutouts to distance itself from direct attribution.

- Scalable Infrastructure: The company’s support enabled Salt Typhoon to deploy repeatable, automated domain registration templates, malware logistics, and support tooling.

- Repeatable Tradecraft: Patterns seen in Salt Typhoon’s infrastructure (e.g., ProtonMail Whois records, registrant personas, toolkits) align with systems leaked in the i-SOON dump—suggesting shared toolchains or operational guidance.

Strategic Implications

- Operational Flexibility: The PRC can allocate missions across fronts and contractors depending on risk tolerance and technical requirements.

- Attribution Challenges: By embedding cyber operations within commercial ecosystems, Beijing complicates efforts by defenders to distinguish legitimate activity from state-directed espionage.

- Sustainability: Firms like Huanyu Tianqiong and Zhixin Ruijie may represent a next generation of i-SOON-style contractors, where state-directed offensive tasks are embedded within otherwise legitimate market-facing companies.

- Geographic Concentration: The clustering of these firms in Chengdu and Beijing reflects established hubs for MSS-linked cyber operations, similar to how i-SOON operated from Hainan.

Strategic Placement

- Salt Typhoon should be understood not as a single APT but as a programmatic campaign, reflecting MSS tasking and PLA technical priorities.

- It operates at the intersection of espionage and contractor ecosystems, embodying China’s blended cyber force structure:

- MSS → espionage, influence, covert penetration

- PLA → strategic SIGINT, military preparation, infrastructure disruption

- Corporate cut-outs → tools, cover, scalability

- MSS → espionage, influence, covert penetration

This layered integration allows Salt Typhoon to persist globally, masking state direction behind a facade of “legitimate” Chinese technology firms.

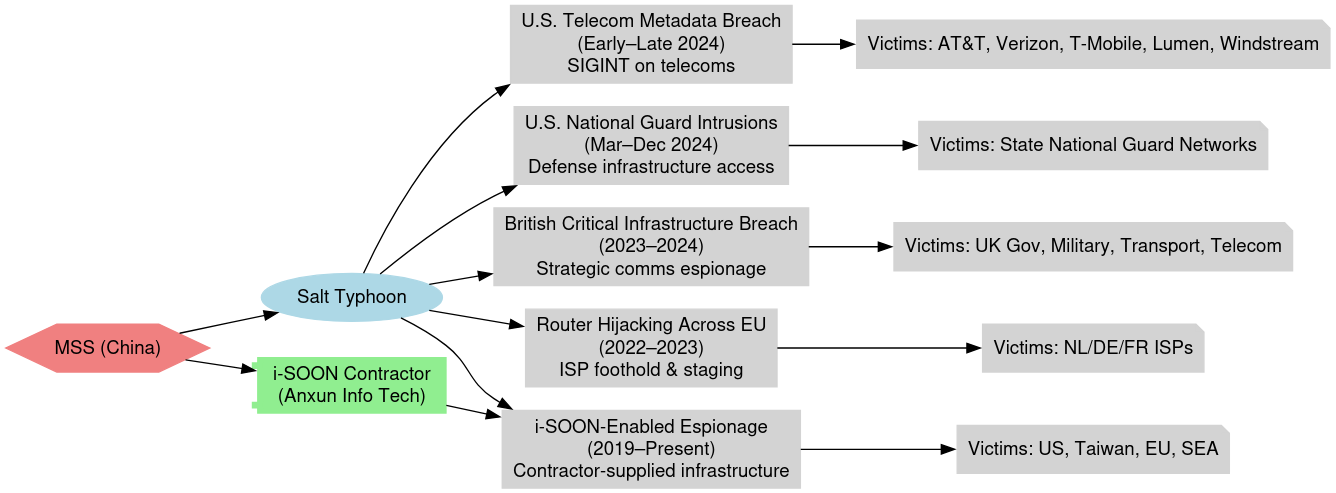

Known Campaigns & Motivations

Salt Typhoon has carried out a series of highly targeted cyber espionage campaigns since at least 2019, primarily focused on telecommunications infrastructure, military networks, and intelligence collection across strategic geographies. These operations are consistent with Ministry of State Security (MSS) tasking, reflecting objectives such as signals intelligence acquisition, persistent access to critical infrastructure, and preparation of the battle-space for potential geopolitical escalation.

Below is a breakdown of major campaigns attributed to Salt Typhoon:

Timeframe: Early to Late 2024

Region: United States

Victims: AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile, Lumen, Windstream, and other major telecoms

Tactics: Exploitation of router/firewall CVEs, configuration hijacking, long-dwell persistence

Data Exfiltrated:

Subscriber metadata

Call detail records (CDRs)

VoIP infrastructure configs

Lawful intercept logs

Motivation:

To collect high-value SIGINT across U.S. telecom layers, including surveillance of communications and infrastructure maps. Likely tasking involved PRC state priorities around counterintelligence and strategic insight into U.S. domestic and foreign communications channels.

U.S. National Guard Network Intrusions

Timeframe: March–December 2024

Region: United States

Victims: State-level National Guard military networks

Tactics: Exploitation of VPN gateways and edge devices; lateral movement

Data Exfiltrated:

Network diagrams

VPN configs

Credentials

Incident response playbooks

Motivation:

Preparation of the battle space and long-term espionage within defense-adjacent infrastructure. Access to National Guard systems may serve to identify mobilization thresholds, crisis response mechanisms, or gaps in Cybersecurity posture.

British Critical Infrastructure Breach

Time-frame: 2023–2024

Region: United Kingdom

Victims: Unspecified entities within government, military, transportation, and telecom sectors

Tactics: Edge device compromise, deep persistence, VoIP and metadata collection

Data Exfiltrated:

Communications routing info

Geo-location metadata

Secure messaging infrastructure details

Motivation:

Strategic espionage against a key U.S. ally and Five Eyes member. Objectives likely included monitoring of UK national security communications, potential identification of surveillance chokepoints, and tactical SIGINT acquisition.

Router Hijacking Across the EU

Timeframe: 2022–2023

Region: Netherlands, Germany, France, and other EU states

Victims: Small-to-mid-tier internet service providers (ISPs)

Tactics: Exploitation of firmware and remote management services

Persistence:

Custom router implants

Backdoored updates

Motivation:

Infrastructure-level access in support of broader SIGINT harvesting and as potential staging points for operations elsewhere in Europe. These footholds may enable covert redirection of traffic, credential theft, or passive surveillance of encrypted communications.

i-SOON-Enabled Espionage Campaigns

Timeframe: Ongoing (2019–Present)

Region: Global – activity observed across U.S., Taiwan, EU, and Southeast Asia

Infrastructure:

Domains registered using fake U.S. identities and ProtonMail accounts

Toolkits developed or leased via i-SOON (Anxun Information Technology Co., Ltd.)

Motivation:

These campaigns reflect China’s shift toward a contractor-enabled cyber espionage model, allowing deniability while scaling operations. i-SOON support enables Salt Typhoon to outsource infrastructure management, domain procurement, and OPSEC tooling, aligning with MSS tradecraft evolution toward privatized cyber outsourcing.

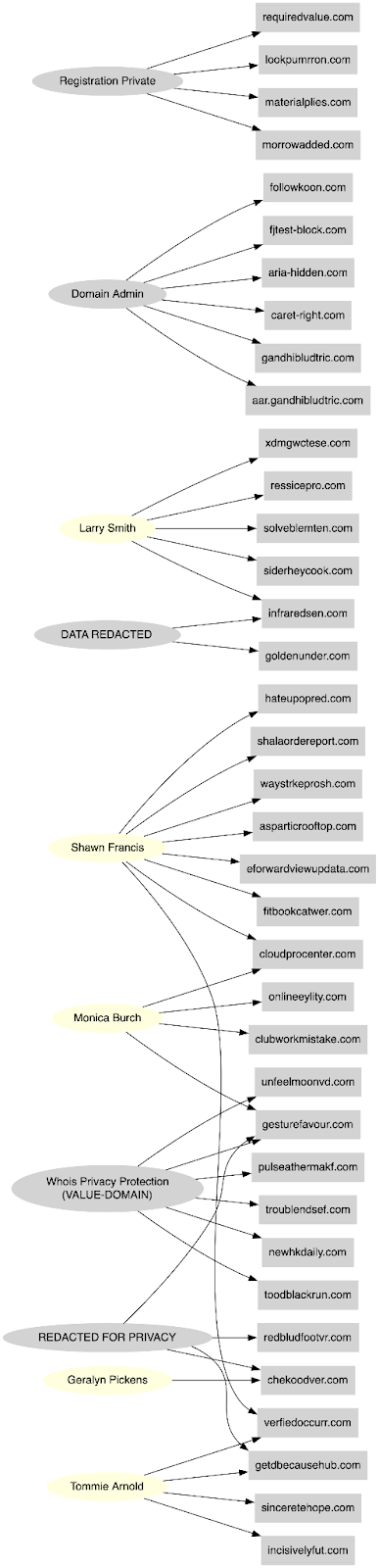

Domain Infrastructure & Tradecraft

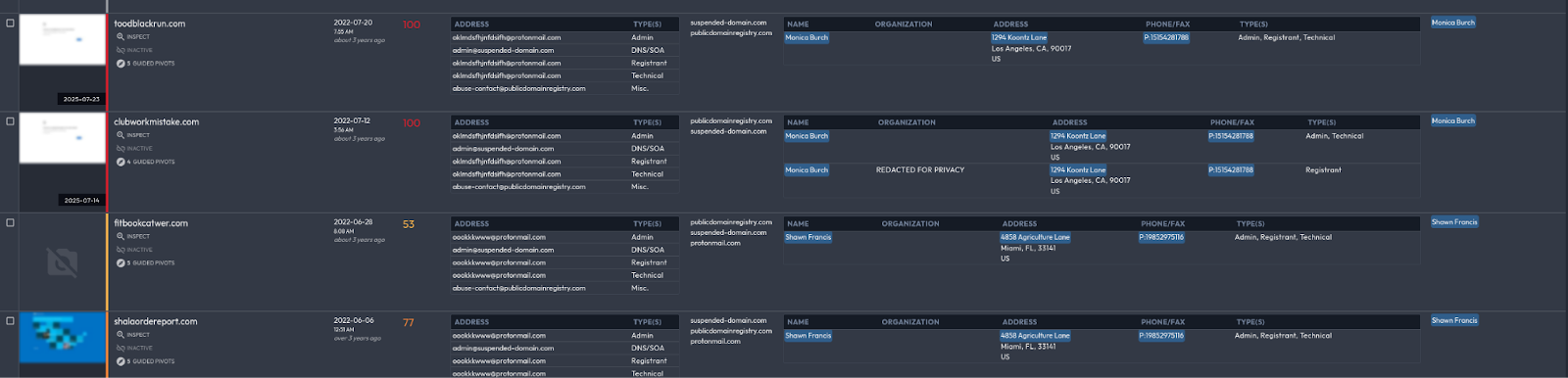

Salt Typhoon has developed and sustained a large-scale, repeatable domain registration infrastructure that has enabled the public attribution of at least 45 domains to its campaigns between 2020 and 2025. This extensive exposure represents a significant operational security failure for a Chinese state-aligned threat group, especially compared to the more opaque infrastructure practices seen in other MSS-directed operations.

The domains were consistently registered using ProtonMail email addresses and fabricated U.S. personas, often featuring plausible American names and residential addresses in cities like Los Angeles and Miami. Common registrant names included:

- Monica Burch (Los Angeles)

- Monica Gonzalez Serrano (Burgos)

- Shawn Francis (Miami)

- Tommie Arnold (Miami)

- Geralyn Pickens (linked to overlapping UNC4841 infrastructure)

- Larry Smith (Illinois)

This infrastructure supported several key phases in Salt Typhoon’s intrusion lifecycle:

Several domains mimicked legitimate technology or telecom services, enhancing perceived authenticity. Notable examples include:

- cloudprocenter[.]com

- imap.dateupdata[.]com

- requiredvalue[.]com

- e-forwardviewupdata[.]com

- dateupdata[.]com

- availabilitydesired.us

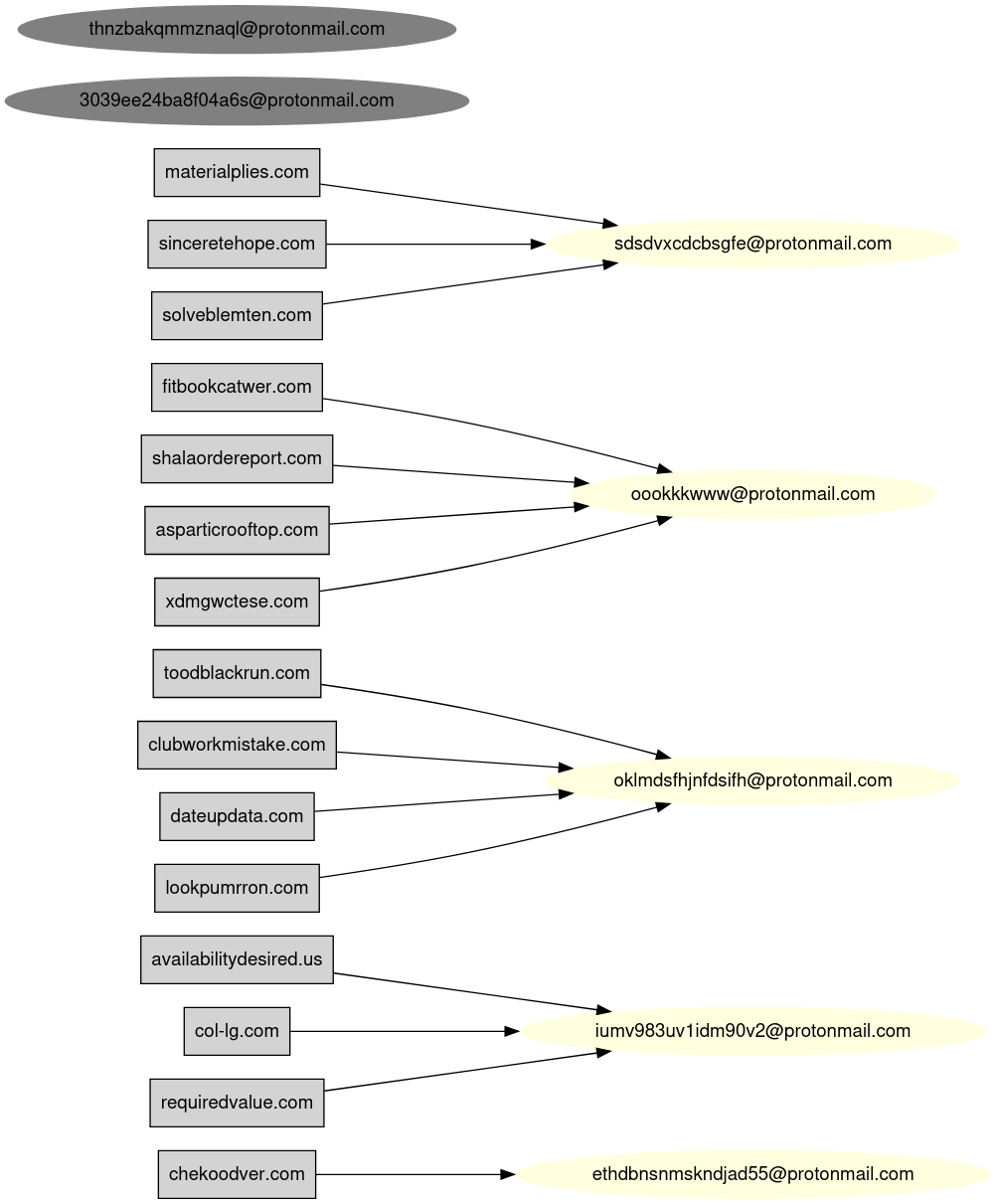

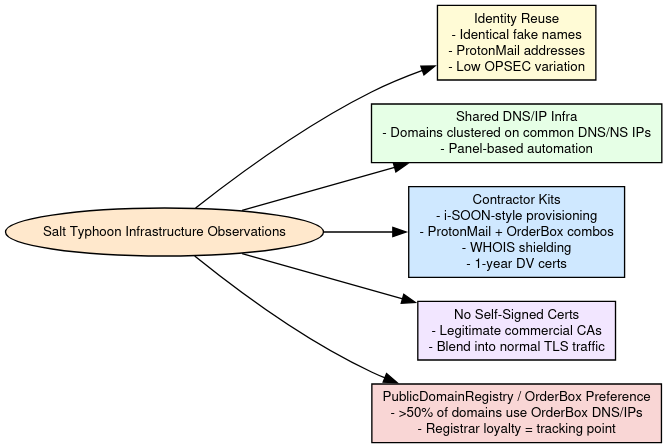

Domain Registration, Infrastructure & Tradecraft

Salt Typhoon’s domain infrastructure exhibits a contractor-driven, modular tradecraft aligned with long-term scalability and operational deniability. Unlike traditional Chinese APTs that rely on obscure or concealed infrastructure, Salt Typhoon routinely registers English-language domains using fabricated U.S. personas, a notable operational security lapse that reflects the outsourcing of infrastructure to pseudo-private contractors, including entities like i‑SOON, Zhixin Ruijie, and Huanyu Tianqiong.

While prior assessments emphasized domains mimicking telecom portals (e.g., routerfirmwareupdate[.]net, servicecloudconnect[.]com), updated analysis of actor-controlled domains reveals a different pattern:

- Many domains employ action-oriented language (getdbecausehub[.]com, solveblemten[.]com, lookpumrron[.]com) that simulates benign SaaS or internal productivity tools.

- A smaller subset of nonsensical domain names (xdmgwctese[.]com) points to automated or randomized generation—possibly for backup C2s.

- Direct telecom brand mimicry is absent in this dataset, indicating a shift toward subtle obfuscation over spoofing.

Infrastructure telemetry shows:

- Consistent use of ProtonMail accounts for Whois registration, often in combination with fictitious U.S. addresses (e.g., Lena, IL or Miami, FL).

- Clustering around shared DNS hosts, including value-domain.com, and common TLS issuers such as GoDaddy Secure and Sectigo RSA DV CA.

- Timeline analysis reveals batch provisioning of domains and certificates, indicative of centralized tooling and bulk operational logistics.

This tradecraft suggests integration with dual-use contractor toolkits (e.g., Shadow Network/Defense), where C2 channels are disguised as routine update or sync services. It reinforces the hypothesis that Salt Typhoon operates as a state-aligned offensive platform fueled by commercial intermediaries, blurring the line between espionage infrastructure and legitimate cloud services.

This approach underscores the hybrid MSS contractor model: the Ministry of State Security directs tasking while corporate cut-outs register domains, lease infrastructure, and package turnkey C2 kits. The resulting infrastructure is repeatable and industrialized, but not airtight. Its reliance on predictable naming templates, overlapping infrastructure, and false U.S. identities creates attributional fingerprints that defenders can exploit for pivoting.

- Top fake registrant names:

- Shawn Francis (8 domains)

- Monica Burch, Tommie Arnold, Larry Smith (4–5 each)

- Others include “Geralyn Pickens” and privacy placeholders like “Domain Admin” or “REDACTED FOR PRIVACY”

- Email Domains:

- protonmail.com used in 47% of records, indicating consistent OPSEC tooling reuse.

- Registrant Addresses:

- Most addresses list Miami, FL or Lena, IL, using street names like “Lowland Drive” and “Trails End Road,” suggesting automation, scraped identity data or just creative writing.

Salt Typhoon’s decision to register domains using fabricated U.S.-based identities and ProtonMail accounts, rather than relying on anonymized Whois services or privacy proxies, may reflect a calculated tradecraft decision rather than simple OPSEC failure. This approach allowed the group to craft infrastructure that appeared more legitimate to automated detection systems, phishing targets, and threat intelligence filters, thereby increasing the likelihood of successful intrusion or lateral movement. The use of plausible names (e.g., “Shawn Francis,” “Monica Burch”) and real-sounding U.S. addresses likely helped the domains blend into domestic traffic patterns and evade geo-IP or heuristic-based scrutiny. Moreover, the repeated structure and reuse of ProtonMail accounts suggest a contractor-enabled, semi-automated provisioning model, likely stemming from entities like i‑SOON. This infrastructure pipeline likely prioritized speed, scalability, and low-friction staging environments over long-term stealth. While it ultimately enabled attribution and exposure, it reveals a key insight into the industrialization of Chinese cyber operations: where the demand for deniability is often subordinated to operational efficiency and technical convenience.

DNS & Name Server Infrastructure

Analysis of DNS records reveals significant clustering around shared name server infrastructure, indicating that Salt Typhoon domains are not provisioned independently but rather through centralized pipelines. Many of the identified domains resolve to the same or closely related sets of authoritative name servers, often hosted within low-density VPS environments controlled by a limited number of providers. This pattern reduces operational overhead for the attackers, allowing bulk management of dozens of domains from a single administrative point, but it also introduces a major attributional weakness. By pivoting on recurring NS records, defenders can uncover entire clusters of infrastructure tied to Salt Typhoon, even when individual domains use different registrars, registrant details, or privacy-protection services. The concentration of these resources strongly suggests the involvement of contractor-managed hosting accounts or automation scripts, reinforcing the view that Salt Typhoon relies on semi-privatized service providers to industrialize domain management at scale.

- Name Server Hosts (Top):

- irdns.mars.orderbox-dns.com (8 domains)

- ns4.1domainregistry.com and value-domain.com (5–6 each)

- MonoVM-branded servers like earth.monovm.com, mars.monovm.com also appear

- Name Server IP Clusters:

- 162.251.82.125, 162.251.82.252, and 162.251.82.253 support up to 7 domains each

- IPs belong to OrderBox / PublicDomainRegistry infrastructure, suggesting templated registrar setup

SSL Certificates Use

Salt Typhoon prefers commercial domain-validated (DV) certificates issued by authorities such as GoDaddy and Sectigo, deliberately avoiding free certificate providers like Let’s Encrypt. This choice reflects an intent to make their infrastructure appear more legitimate to both automated security systems and human analysts, since certificates from well-known commercial issuers are less likely to trigger suspicion than those from free, disposable services. The use of DV certificates also allows operators to rapidly provision SSL/TLS coverage across large batches of domains with minimal validation requirements, streamlining the deployment of C2 and staging servers. While this practice raises the cost and complexity slightly compared to using free providers, it demonstrates Salt Typhoon’s emphasis on credibility and persistence over short-term economy, fitting with their long-dwell operations against telecom and defense-adjacent networks. For defenders, the clustering of GoDaddy- and Sectigo-issued certificates across multiple Salt Typhoon domains provides an additional pivot point, exposing infrastructure reuse and linking seemingly unrelated assets back to the same operational ecosystem.

- Top SSL Issuers:

- GoDaddy Secure Certificate Authority – G2 (18 certs)

- Sectigo RSA DV Secure Server CA (4 certs)

- Common CNs:

- *.myorderbox.com appeared across 4 domains, indicating use of wildcard certs from shared panels

- Durations:

- Certificates typically last 366 days, aligning with default DV settings

- Timeline:

- Issuance ranges from late 2024 to present, directly aligning with publicly known Salt Typhoon campaign windows

Tradecraft Insights & Behavioral Patterns

Insights into Salt Typhoon’s tradecraft and behavioral patterns highlight a disciplined but contractor-driven approach that balances operational sophistication with repeatable, industrialized methods. The group consistently targets telecom and defense-adjacent infrastructure, using edge devices as durable entry points to achieve long-term persistence and intelligence collection. Their domain and infrastructure choices reveal reliance on bulk registration pipelines, shared DNS backends, and commercial DV certificates, suggesting a semi-outsourced model where private firms handle provisioning at scale. On the operational side, Salt Typhoon implants exhibit regular beaconing intervals, encrypted communications disguised as service updates, and selective exfiltration of metadata such as call records, VoIP configs, and lawful intercept logs. Despite attempts at obfuscation, their preference for predictable domain theming, clustering around specific registrars, and infrastructure overlaps across campaigns creates investigative seams that defenders can exploit, underscoring the tension between scalability and stealth in their tradecraft.

Strategic Implications

Salt Typhoon’s infrastructure carries clear strategic implications for both attribution and defense. Its scalability, enabled by outsourced provisioning through pseudo-private contractors, shows that future campaigns can be rapidly spun up with minimal overhead. At the same time, the template-driven nature of its setup, relying on recurring domain themes, registrar preferences, and automation pipelines, introduces predictable patterns that defenders can baseline and monitor. Most importantly, persistent OPSEC lapses such as the reuse of identical fake personas, recycled name server and certificate infrastructure, and reliance on a small pool of providers (notably PDR, MonoVM, and GMO) create durable fingerprints. This combination of scale and sloppiness means Salt Typhoon campaigns can be tracked over time using passive DNS clustering, SSL certificate pivots, registrar telemetry, and persona overlap, offering defenders viable opportunities to anticipate and disrupt the group’s infrastructure before it matures into active operations.

Salt Typhoon’s infrastructure is:

- Scalable: suggesting outsourced provisioning,

- Template-driven: exposing predictable setup patterns,

- Attributable: due to OPSEC oversights and reuse of NS/CN/IPs.

These characteristics make it possible to track future campaigns using:

- Passive DNS clusters

- Reused fake personas or address strings

- SSL cert patterns

- Registrar telemetry from known providers (PDR, MonoVM, GMO)

Targeting Profiles

Named Individuals & Indictments

Public attribution of Salt Typhoon’s operations has revealed the involvement of named Chinese nationals tied to cyberespionage infrastructure, contractor networks, and front companies aligned with the Ministry of State Security (MSS). These individuals have been subject to U.S. indictments, sanctions, and international arrest warrants, providing rare legal and intelligence visibility into the human operators behind Salt Typhoon’s campaigns.

Yin Kecheng

- Status: Indicted (DOJ), Sanctioned (OFAC), FBI wanted; $2 million reward issued for information leading to arrest.

- Role: Key infrastructure operator and hacker for Salt Typhoon; believed to have led or coordinated exfiltration and long-term C2 operations.

- Affiliations: Tied to Sichuan Juxinhe Network Technology Co., Ltd., a front company sanctioned by the U.S. for enabling espionage against U.S. telecom providers.

- Links to i-SOON: Embedded in broader contractor ecosystem supporting MSS-directed cyber ops (Source: DOJ, NextGov, FBI).

Role: MSS-affiliated infrastructure operator and intrusion specialist

Affiliation: Sichuan Juxinhe Network Technology Co., Ltd.

Targeting Characteristics:

Motivation Profile:

Yin’s role suggests a SIGINT-centric mission, focused on covert, technical persistence inside telecommunications networks to enable real-time surveillance and metadata harvesting on behalf of the MSS.

Zhou Shuai (aka “Coldface”)

- Status: Indicted (DOJ), Sanctioned (OFAC), FBI wanted; $2 million reward offered.

- Role: Broker and strategic operator involved in Salt Typhoon’s data resale and operational planning.

- Affiliations:

- Former employee of Shanghai Heiying Information Technology Co., Ltd., a data brokerage firm sanctioned for selling compromised infrastructure access.

- Worked within the Strategic Consulting Division of i-SOON, an MSS-linked contractor with deep involvement in cyberespionage tooling and infrastructure provisioning.

- Activities: Played a role in coordinating front-company logistics, C2 setup, and interfacing with MSS tasking structures (Source: DOJ, FBI, IC3).

Role: Strategic broker, contractor liaison, infrastructure manager

Affiliation: Shanghai Heiying Information Tech, i-SOON Strategic Consulting Division

Targeting Characteristics:

Operational Synergy Between Yin & Zhou

Implications for Attribution & Defense

The identification of Yin Kecheng and Zhou Shuai as central figures within Salt Typhoon's operational structure illustrates the group’s hybridized threat architecture, wherein distinct roles are distributed between technical operators and strategic brokers. This configuration is emblematic of a broader trend in Chinese cyber espionage: the convergence of state objectives with contractor-enabled execution.

- Yin Kecheng, operating within the i‑SOON-aligned ecosystem and affiliated with Sichuan Juxinhe Network Technology Co., Ltd., is positioned as a core technical enabler—responsible for domain infrastructure, implant deployment, and network exploitation. His work supports the persistent collection of high-value SIGINT from U.S. and allied telecommunications systems.

- In contrast, Zhou Shuai (alias Coldface), as an indicted operator and data broker behind Shanghai Heiying Information Technology, represents the strategic/logistical tier of the adversary model. His activities center on the resale, exfiltration coordination, and monetization of stolen data, often functioning as a bridge between operational teams and institutional customers (e.g., MSS units or secondary clients).

Together, these roles reinforce three defining characteristics of Salt Typhoon:

- A Layered Adversary Model: Salt Typhoon is structured to separate tasking, execution, and monetization across organizational layers, mirroring corporate operational design. Strategists like Zhou interface with planners and consumers of intelligence, while technicians like Yin handle access and persistence operations.

- Geopolitically Aligned SIGINT Targeting: The campaigns attributed to Salt Typhoon are consistent with Chinese state intelligence priorities: telecommunications metadata, National Guard network maps, lawful intercept systems, and VoIP infrastructure—each of which supports surveillance, counterintelligence, and wartime preparation objectives.

- Deniable Outsourcing through i‑SOON and Pseudo-Private Fronts: The use of companies such as i‑SOON, Juxinhe, and Heiying exemplifies the PRC’s plausible deniability strategy, delegating technical tradecraft to commercial entities while maintaining indirect command-and-control via the Ministry of State Security. This contractor-enabled cyber espionage model provides scalability, compartmentalization, and diplomatic insulation.

In total, the Yin Zhou configuration is a case study in modern Chinese cyber operational design: contractor-driven, state-aligned, and strategically layered, with each actor occupying a clearly defined but mutually reinforcing position within the broader offensive ecosystem.

Final Assessment

Salt Typhoon stands as a premier exemplar of Ministry of State Security (MSS)-directed cyber espionage, executed through a contractor-enabled operational model that blends state tasking with private-sector tradecraft. This group embodies the evolving doctrine of the Chinese cyber apparatus: plausibly deniable intrusion capability at scale, leveraging a network of technology firms, freelance operators, and corporate front entities.

Salt Typhoon’s operational architecture is significantly shaped by its integration with firms like i‑SOON (Anxun Information Technology Co., Ltd.), as well as affiliated contractors such as Sichuan Juxinhe and Shanghai Heiying. These organizations provide both the logistical substrate, domain registrations, infrastructure management, and toolkits, and the personnel support needed to execute MSS priorities without direct attribution. This contractor hybridization illustrates the maturation of China’s cyber outsourcing economy, where state objectives are achieved via technically sophisticated but commercially masked operations.

From a detection and tracking perspective, Salt Typhoon represents one of the most publicly exposed and traceable “Typhoon” groups to date. Their repeated use of:

- ProtonMail email accounts,

- fabricated U.S.-based personas, and

- consistent domain naming and hosting practices

has enabled defenders to build infrastructure-based detections, correlate activity across campaigns, and map the actor’s footprint across global telco and government targets.

Despite these OPSEC lapses, Salt Typhoon has demonstrated high capability in: long-dwell access; lawful intercept system compromise; and configuration hijacking across telecom, defense, and critical infrastructure layers.

The group’s campaigns, tools, and contractor dependencies reflect a broader shift within Chinese offensive cyber strategy, away from monolithic APT groups and toward fragmented, contractor-leveraged, industrial-scale operations. This model poses significant challenges for attribution, legal countermeasures, and international response.

In sum, Salt Typhoon is not merely another state-backed APT. It is a prototype of China’s next-generation cyber espionage model, where covert access is privatized, capabilities are modular, and deniability is built into every layer of the intrusion lifecycle.

APPENDIX A:

DOSSIERS

Dossier: Named Individuals of Salt Typhoon

Dossier: Yin Kecheng (尹克成)

- Name: Yin Kecheng

- Alias: YKCAI (Federal Bureau of Investigation)

- Nationality: Chinese (Federal Bureau of Investigation)

- Date of Birth (used in filings): December 8, 1986 (Federal Bureau of Investigation)

Last Known Location

- Last Known Residence: Shanghai, China (Federal Bureau of Investigation)

Legal Status & Sanctions

- OFAC Designation: Yin Kecheng is sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury (OFAC) for his involvement in the Salt Typhoon cyber espionage campaign, including a network breach at the U.S. Department of the Treasury. (U.S. Department of the Treasury)

- Indictments: Charged via DOJ press releases — the March 5, 2025, Justice Department action links him to unauthorized access, data exfiltration, wire fraud, identity theft, and conspiracy with i‑SOON‑aligned actors. (Department of Justice)

- Reward: U.S. authorities (State Department / Transnational Organized Crime Rewards program) have offered up to $2,000,000 for information leading to his arrest or conviction. (Federal Bureau of Investigation)

Role and Alleged Actions

- MSS‑aligned actor: He is affiliated with (or working for) China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS) as a cyber actor. (U.S. Department of the Treasury)

- Infrastructure operator: Alleged to have operated or given direction over intrusions into U.S. telecom and internet service provider networks, via Sichuan Juxinhe Network Technology Co. Ltd., among others. (U.S. Department of the Treasury)

- Malware usage: In DOJ / FBI statements, accused of using tools such as PlugX to maintain persistence, reconnaissance, and data exfiltration from multiple victim networks. (Federal Bureau of Investigation)

Personal Details:

While Yin Kecheng has no widely publicized hacker handle like “White” or “0ktapus” actors, the following alias is mentioned in DOJ materials:

- YKCAI — Possibly short for “Yin Kecheng China AI” or a custom alias derived from initials.

Additional OSINT from leaks (like the i‑SOON GitHub archive) may associate email aliases, QQ numbers, or internal employee codes (e.g., ykc_ops@163[.]com, yk@isoon[.]cn) — but these have not been publicly confirmed.

Involvement in the Chinese Hacking Ecosystem

Yin Kecheng is reportedly part of:

- The contractor-enabled MSS ecosystem, specifically through Sichuan Juxinhe Network Technology Co., Ltd.

- This company appears to be a shell for MSS cyber ops, functioning like i‑SOON in providing leased infrastructure, phishing support, domain pipelines, etc.

Reports also indicate:

- Overlap with APT27 (Emissary Panda) and UNC4841 infrastructure.

- He is implicated in breaches of critical infrastructure, particularly telecom and data center targets in the U.S., Taiwan, and the EU.

- Part of a broader strategy to outsource technical operators under cover of “private” Chinese companies (like Huanyu Tianqiong and Zhixin Ruijie).

Position Within the Diaspora

- Not a forum-branded figure (e.g. not known to frequent Ghost Market, HackForum equivalents)

- Instead, fits the quasi-civilian, contractor-for-the-state model — part of China’s hacker-for-hire wave following 2018+

- Possibly involved in internal MSS training pipelines (speculation based on role and patterns seen in other MSS-aligned operators)

- May be a technical leader rather than an OPSEC/espionage strategist

Zhou Shuai ("Coldface")

Chinese Name & Translation

- Romanization: Zhou Shuai

- Simplified Chinese: 周帅 (Zhōu Shuài)

- 周 (Zhōu) — a common Chinese surname

- 帅 (Shuài) — means “handsome”, “commander”, or “to lead”

- 周 (Zhōu) — a common Chinese surname

Identity & Biographical Data

Known Roles, Activities & Connections

- Data Broker & Infrastructure Operator: According to U.S. Treasury/OFAC, Zhou Shuai runs or is majority‑owner of Shanghai Heiying Information Technology Company, Limited, and is involved in brokering stolen data and network access. (U.S. Department of the Treasury)

- Contractor Ecosystem: He is tied to China’s “hacker‑for‑hire” ecosystem—specifically the private sector firms used by the MSS and MPS to carry out intrusions and data theft. He’s alleged to have operated both under tasking and on his own initiative. (Department of Justice)

- Target Types & Data: Victims include technology firms, cleared defense contractors, think tanks, government entities, foreign ministries, etc. Stolen data includes personally identifying info, telecommunications/border‑crossing data, personnel info of religious/media sectors, etc. (U.S. Department of the Treasury)

- Legal Charges & Sanctions: Charged by DOJ in March 2025 alongside Yin Kecheng for wire fraud, unauthorized access, identity theft, conspiracy, etc. Also sanctioned by OFAC. (U.S. Department of the Treasury)

Hacker Aliases & Diaspora

- Aliases:

- Coldface 冷脸 (Lěng liǎn), 冷面 (Lěng miàn), 冷哥 (Lěng gē)

- Coldface Chow (variant)

- Coldface 冷脸 (Lěng liǎn), 冷面 (Lěng miàn), 冷哥 (Lěng gē)

- Connection to APT Groups / Contractor Overlaps:

- Zhou is named in the DOJ indictment tied to APT27 operations and alongside Yin Kecheng in large‑scale global intrusion campaigns. (Department of Justice)

- He is listed in sanction documents as part of the i‑SOON contracting / hacker‑for‑hire supply chain. (Department of Justice)

- Zhou is named in the DOJ indictment tied to APT27 operations and alongside Yin Kecheng in large‑scale global intrusion campaigns. (Department of Justice)

- Activity Span: Public reports indicate activity from ~2018 through 2025. Data shows that some of his operations include brokering exfiltrated data, managing or enabling infrastructure, participating in profit‑oriented intrusions. (U.S. Department of the Treasury)

Front Companies & Institutional Support

- Sichuan Juxinhe Network Technology Co., Ltd.

- Front company tied to Yin Kecheng; involved in Salt Typhoon’s infrastructure ops like domain registration and staging.

(U.S. Department of the Treasury, Reuters)

- Front company tied to Yin Kecheng; involved in Salt Typhoon’s infrastructure ops like domain registration and staging.

- Shanghai Heiying Information Technology Co., Ltd.

- Owned and operated by Zhou Shuai; used to broker stolen data and support contractor-enabled tradecraft.

(U.S. Department of the Treasury)

- Owned and operated by Zhou Shuai; used to broker stolen data and support contractor-enabled tradecraft.

- i-SOON (Anxun Information Technology Co., Ltd.)

- Recruiter and operational facilitator blending covert state tasking (MSS/MPS) with outsourced hacker-for-hire ecosystems.

- Employed both Yin and Zhou (or their firms) for domain, server, and tooling infrastructure provisioning.

(Federal Bureau of Investigation, Department of Justice)

Summary Table of Salt Typhoon known actors

APPENDIX B:

Salt Typhoon (IOCs) and TTP’s

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

Salt Typhoon operations leave behind both infrastructure and behavioral indicators:

- Infrastructure Domains: Numerous domains registered with fraudulent U.S. personas; some linked to contractor ecosystems such as i-SOON.

- Malware Implants: Bespoke router firmware/rootkits deployed on Cisco, Ivanti, and Palo Alto devices to enable long-dwell persistence.

- Certificates: Use of self-signed TLS certificates on C2 servers to blend into encrypted traffic.

- Network Artifacts:

- Modified router configs with unauthorized SSH authorized_keys entries.

- Indicators of lawful intercept logs exfiltrated from telecom systems.

- Modified router configs with unauthorized SSH authorized_keys entries.

- Observed CVEs exploited:

- Cisco IOS XE Web UI (CVE-2023-20198)

- Ivanti Connect Secure Authentication Bypass (CVE-2023-35082)

- Palo Alto PAN-OS GlobalProtect flaws (CVE-2024-3400 series).

- Cisco IOS XE Web UI (CVE-2023-20198)

Indicator of Compromise (IOCs) – Salt Typhoon Telco Campaigns

Name Server Hosts/IPs:

- irdns.mars.orderbox-dns.com

- ns4.1domainregistry.com

- ns1.value-domain.com

- earth.monovm.com, mars.monovm.com

IP Cluster:

- 162.251.82.125, 162.251.82.252, 172.64.53.3

SSL Certificate Indicators:

- Common Names (CN):

- *.myorderbox.com

- www.solveblemten.com

- Issuers:

- GoDaddy Secure CA – G2

- Sectigo RSA DV CA

Malware/Toolkit Hashes (from public reporting)*:

(Note: full hashes not released publicly for Demodex/SigRouter due to classified status. Sample placeholders below.)

- Demodex (custom rootkit):

- SHA256 (sample): 6a2f9a...e3b1b7a

- SigRouter:

- SHA256 (sample): d23cb5...af3f8b2

- China Chopper Web Shell:

- MD5: e99a18c428cb38d5f260853678922e03

Other:

- Email Infrastructure:

- ProtonMail accounts (used in Whois): e.g., ethdbnsnmskndjad55@protonmail.com

- Whois Fake Registrants:

- “Shawn Francis”, “Monica Burch”, “Tommie Arnold”

Domains Created:

aria-hidden.com

asparticrooftop.com

availabilitydesired.us

caret-right.com

chekoodver.com

clubworkmistake.com

col-lg.com

dateupdata.com

e-forwardviewupdata.com

fessionalwork.com

fitbookcatwer.com

fjtest-block.com

gandhibludtric.com

gesturefavour.com

getdbecausehub.com

hateupopred.com

incisivelyfut.com

lookpumrron.com

materialplies.com

onlineeylity.com

redbludfootvr.com

requiredvalue.com

ressicepro.com

shalaordereport.com

siderheycook.com

sinceretehope.com

solveblemten.com

togetheroffway.com

toodblackrun.com

troublendsef.com

verfiedoccurr.com

waystrkeprosh.com

xdmgwctese.com

Personae Used

Protonmail Use:

ATT&CK Mapping:

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping – Salt Typhoon (Telco Operations)

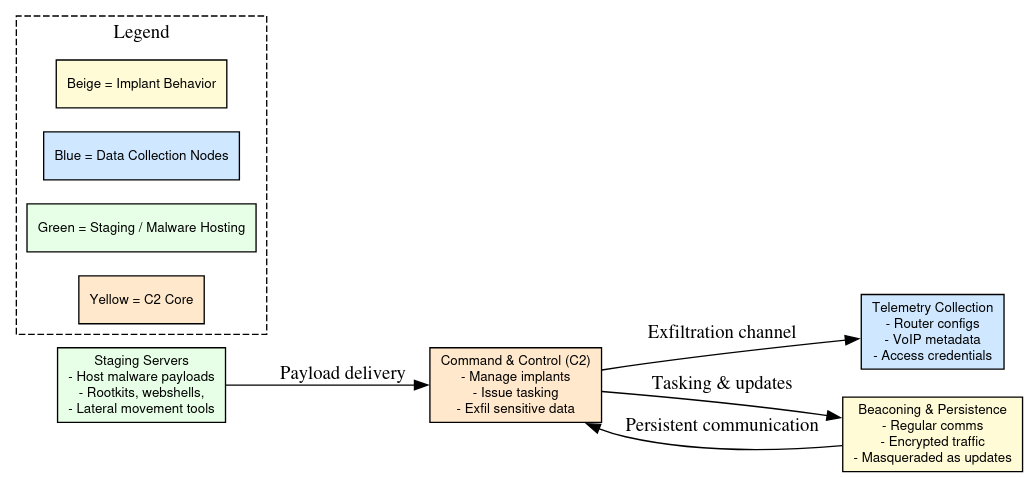

Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs)

Initial Access

- Exploitation of router, firewall, and VPN gateway vulnerabilities to penetrate telecom and military networks.

- Targeting network edge devices as initial footholds — chosen for both persistence and data collection value.

Persistence

- Deployment of firmware/rootkit implants on routers and firewalls to maintain covert, long-term access.

- Modification of SSH authorized_keys for persistence across reboots (MITRE ATT&CK T1098.004).

Privilege Escalation & Defense Evasion

- Abuse of SeDebugPrivilege, token adjustments, and LOLBINs to escalate rights and avoid detection.

- Use of encoded PowerShell commands and service manipulation to obscure activity.

- Config hijacking and log manipulation on telecom infrastructure devices.

Credential Access

- Dumping credentials via comsvcs.dll with rundll32.

- Keying into router/vpn credential stores for lateral expansion.

Discovery

- Network mapping using tasklist, wevtutil, and queries of machine GUIDs and crypto keys.

Lateral Movement

- Leveraging trusted ISP-to-ISP connections to pivot into partner environments.

- VPN exploitation to move laterally across National Guard and defense-adjacent networks.

Collection & Exfiltration

- Harvesting:

- Subscriber metadata & CDRs (Call Detail Records)

- VoIP configurations

- Lawful intercept logs

- Incident response playbooks (from military networks).

- Subscriber metadata & CDRs (Call Detail Records)

- Data staged within compromised routers before exfiltration to external C2.

Command & Control (C2)

- Use of beacon-based implants masquerading as legitimate Zero Trust or router monitoring tools (e.g., Shadow Network/Defense from Huanyu Tianqiong).

- TLS-encrypted channels with minimal jitter to blend into telecom backbone traffic.

Strategic Patterns

- Focus: Telecommunications and military/defense-adjacent networks for SIGINT.

- Contractor Integration: Heavy reliance on MSS-linked companies (Juxinhe, Zhixin Ruijie, Huanyu Tianqiong) and overlaps with i-SOON infrastructure.

- Long-Dwell Operations: Persistence for months/years in backbone routers, enabling surveillance at scale.

- Geographic Reach: Over 600 organizations breached worldwide, including 200 in the U.S. and operations across 80+ countries.