Executive Summary

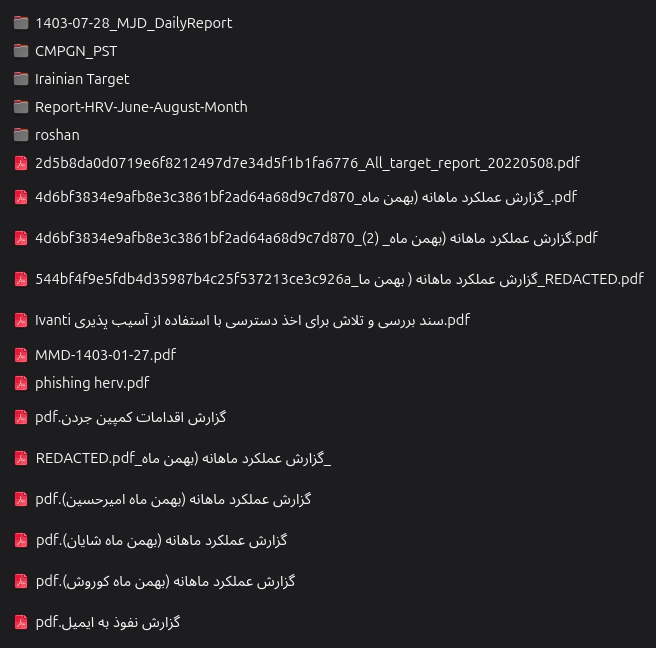

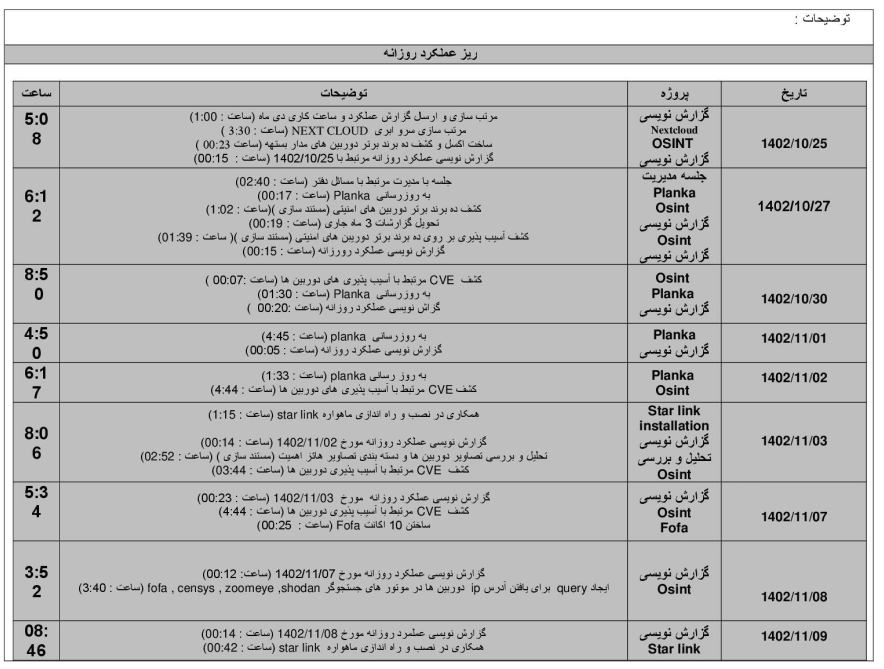

In October, 2025, internal documents from APT35 (also referenced as “Charming Kitten”) were leaked on github. Analysis of the leaked documents reveals a regimented, quota-driven cyber operations unit operating inside a bureaucratic military chain of command. The paperwork reads like internal administration documentation, monthly performance reports, signed supervisor reviews, and redacted KPIs, all oriented around measurable outputs rather than ad hoc opportunism.

Operators routinely file monthly performance reviews that enumerate hours worked, completed tasks, phishing success rates, and exploitation metrics; supervisors then aggregate those inputs into daily and campaign level reports that record credential yields, session dwell times, and high value intelligence extractions. Specialized teams are clearly delineated: exploit development (notably Ivanti and Exchange/ProxyShell tooling), credential replay and reuse, Human Engineering and Remote Validation (HERV) style phishing campaigns, and real time monitoring of compromised mailboxes to sustain HUMINT collection. The paperwork and logs show tasking, handoffs, and oversight , a workflow designed for repeatable collection.

From May 2022 onward, the group executed a region wide Exchange exploitation campaign that paired broad reconnaissance with precise post-exploitation tradecraft. The operation sequence is consistent across the material: build prioritized target queues focused on diplomatic, government, and corporate networks; run ProxyShell, Autodiscover, and EWS attacks; validate shells and extract Global Address Lists (GALs); weaponize harvested contacts with HERV phishing; and maintain sustained intelligence collection through mailbox monitoring and credential reuse. Internal logs, credential dumps, and “performance KPI” templates corroborate this end-to-end tradecraft and reveal deliberate, repeatable processes.

Taken together, the documents show a bureaucratized intelligence collection apparatus with structured tasking, measurable outputs, supervisory oversight, and specialized teams with a focus on systematic access, sustained collection, and exploitable intelligence yields.

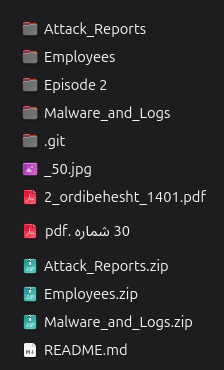

The Dump: Files Analyzed

The uploaded materials form a tightly linked forensic trail that maps both technique and organization. At the technical edge (e.g. infrastructure attacks), memory and server artifacts include an LSASS dump (mfa.tr.txt) containing plaintext credentials and NTLM hashes from MFA.KKTC (Apr 2022), and Dec 2023–Jan 2025 web access logs. These logs show RDP mstshash probes, .env/SendGrid fetch attempts, and wide-ranging curl path scans which document hands-on compromise and opportunistic scanning activity. Exchange artifacts (the ad.exchange.mail_* GAL exports) and annotated ProxyShell target lists (ProxyShell_target_*) show the precise targets and attack surface: diplomatic, government, and large commercial mail systems in Turkey/TRNC, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon, Kuwait, and Korea, with operator notes identifying successful shells, failures, legacyDN issues, and webshell paths.

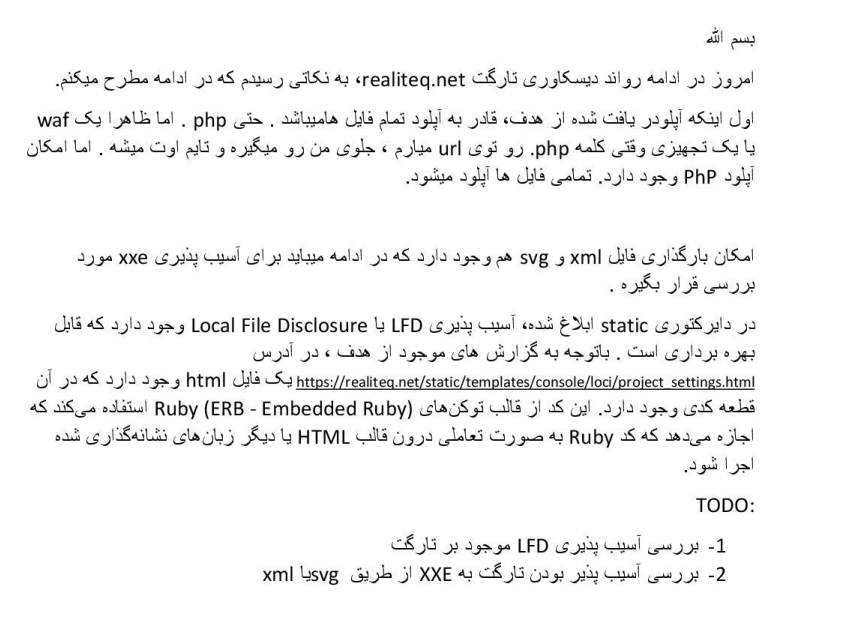

Complementing the technical indicators are playbooks and conversion notes that reveal how vulnerabilities were weaponized: the Ivanti technical review (Ivanti سند بررسی...pdf) translates appliance CVEs into remote code execution paths, while the internal phishing framework (phishing herv.pdf) supplies HERV, style lure templates, campaign metrics, and operational procedures for turning harvested GALs into active collection nodes. Daily operational bookkeeping, HSN / MJD Daily Reports (1403 series) and MJD Campaign Reports (May–July 1403), provide the human layer: KPI tables of lures sent, credentials captured, and mailbox dwell times, plus supervisor commentary and escalation logs into HUMINT and analysis units.

Crucially, the dataset ties virtual access back to a physical workplace: an on premises entry/exit log (entry_exit_form.pdf) confirms operator attendance and supports a picture of centralized tasking and oversight. Image based Farsi PDFs converted via OCR into structured IOC tables and actor maps close the loop by turning visual artifacts into machine-readable indicators (Actor Maps / OCR Extracts). All items are cross-referenced in a DTI evidence repository, producing an end-to-end evidentiary chain from vulnerability research and exploitation, through credential harvesting and phishing, to long term mailbox monitoring and human intelligence exploitation.

Attribution Assessment

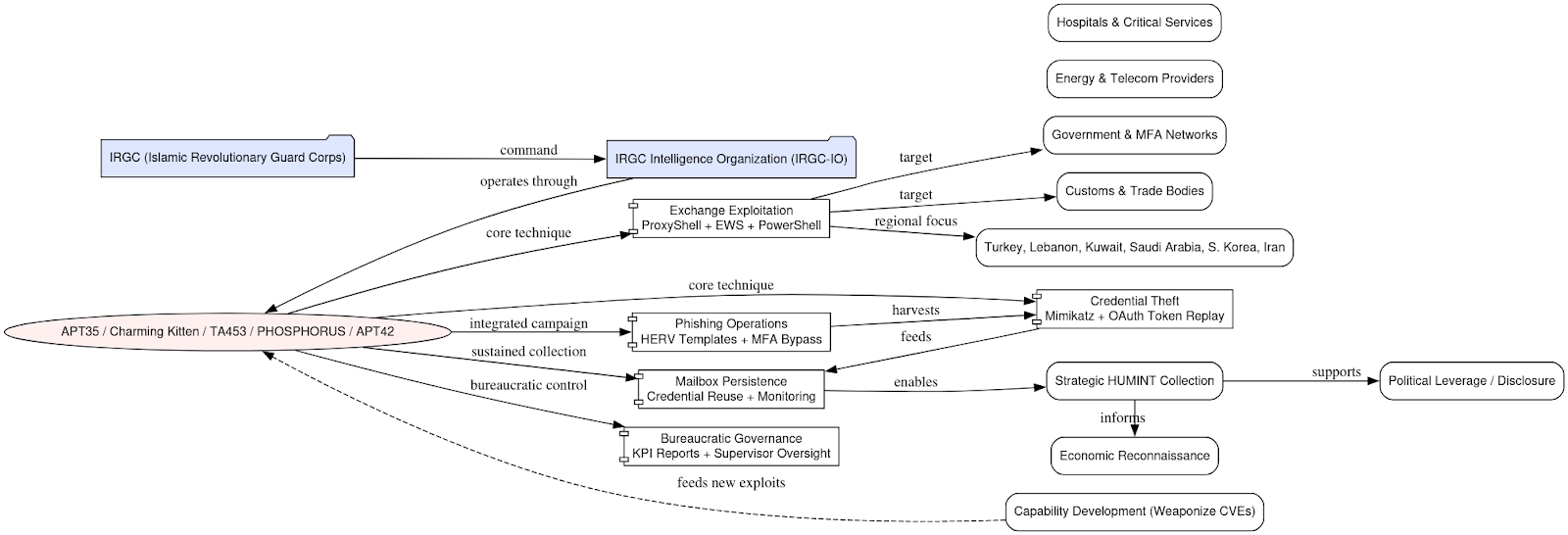

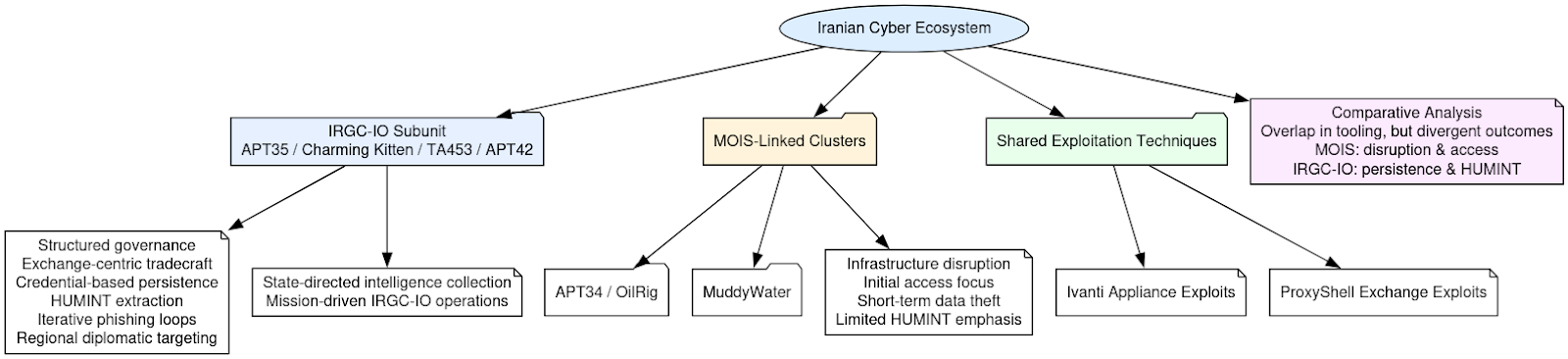

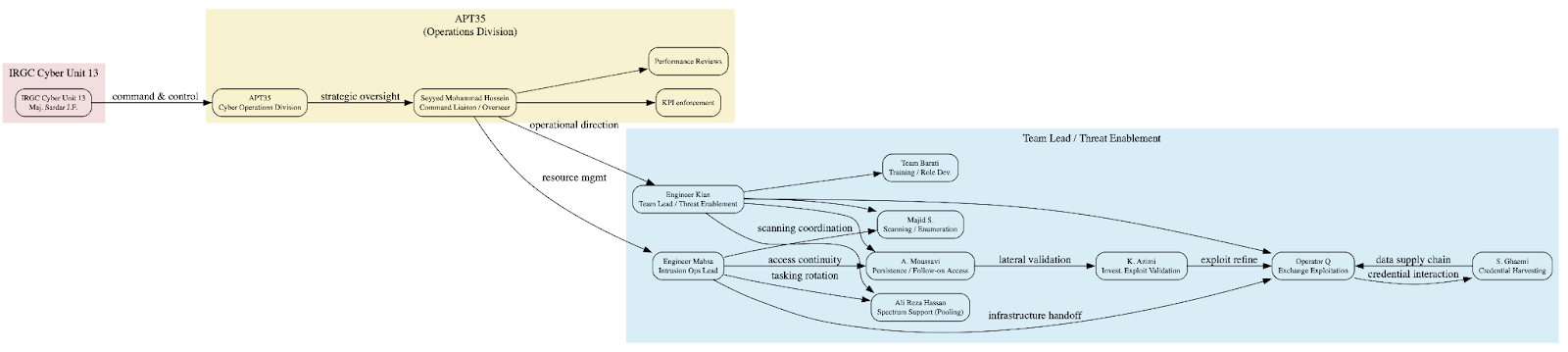

Analysis of the operational data, supporting documentation, and recovered artifacts strongly indicates that the campaigns represented in this dataset were conducted by an element of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Intelligence Organization (IRGC IO), specifically the cluster widely tracked as APT35, also known as Charming Kitten, PHOSPHORUS (Microsoft), TA453 (Proofpoint), or APT42 (Mandiant/Google). This grouping represents the IRGC’s cyber-intelligence arm, dedicated to long term espionage and influence operations.

The alignment between these materials and the known modus operandi of the Charming Kitten ecosystem is unmistakable. The Exchange exploitation wave documented in the leak, which leverages ProxyShell chains, EWS enumeration, and PowerShell automation for Global Address List (GAL) and mailbox extraction, precisely mirrors the tradecraft historically attributed to APT35 and its offshoots.

This focus on diplomatic and governmental mail servers, combined with credential theft and OAuth token replay for persistent access, reflects a campaign objective centered on strategic intelligence collection rather than opportunistic compromise.

The bureaucratic structure observed across the leaked Iranian language documents provides additional confirmation. The templated KPI reports, supervisor approvals, attendance sheets, and quota driven performance metrics all indicate a state-managed, hierarchical organization rather than a criminal or contractor model. These features parallel descriptions from previously leaked internal APT35 materials, which showed identical reporting structures and efficiency-based ranking systems, an unmistakable signature of an institutionalized IRGC unit operating within military command oversight.

Further reinforcing this attribution is the target set. The campaign’s focus on ministries of foreign affairs, customs authorities, energy and telecommunications providers, and other high value sectors in Turkey, Lebanon, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, and domestic Iran aligns precisely with IRGC intelligence priorities. The inclusion of politically sensitive and economically strategic entities demonstrates a dual-purpose mission: HUMINT collection and geopolitical leverage. Such objectives are consistent with the IRGC IO’s remit to gather information for foreign policy, security, and counter intelligence purposes.

While some technical overlaps exist with other Iranian clusters, most notably the use of Ivanti and ProxyShell vulnerabilities, which have also appeared in APT34 (OilRig) and MuddyWater operations, the operational outcome here diverges sharply. Those MOIS-linked groups typically emphasize initial access and infrastructure disruption; in contrast, this actor emphasizes mailbox-level persistence, HUMINT extraction, and iterative phishing loops based on harvested address books. The sophistication and continuity of this collection cycle align squarely with APT35/TA453/APT42 activity patterns observed globally.

In sum, the available evidence points to a state-directed intelligence collection campaign orchestrated by an IRGC IO (Information Operations) subunit operating under the Charming Kitten/APT35 umbrella. The unit’s hallmarks – structured governance, Exchange-centric tradecraft, credential, based persistence, and regionally focused targeting – identify it as a disciplined, mission-driven element within Iran’s broader cyber-intelligence apparatus, functioning as a modern digital extension of the IRGC’s traditional human intelligence mission set.

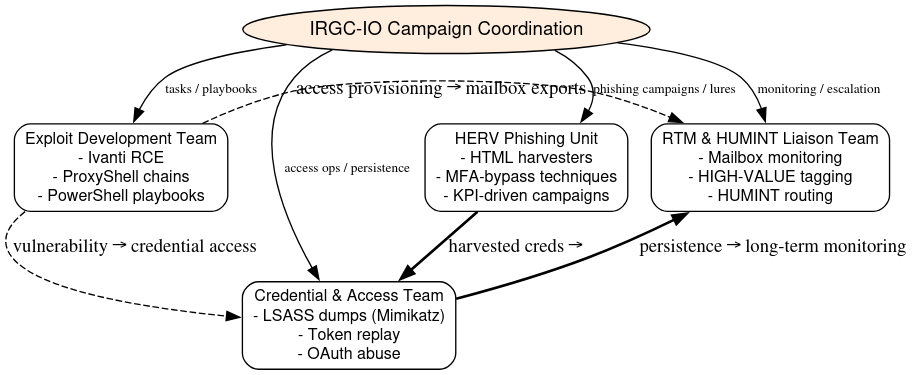

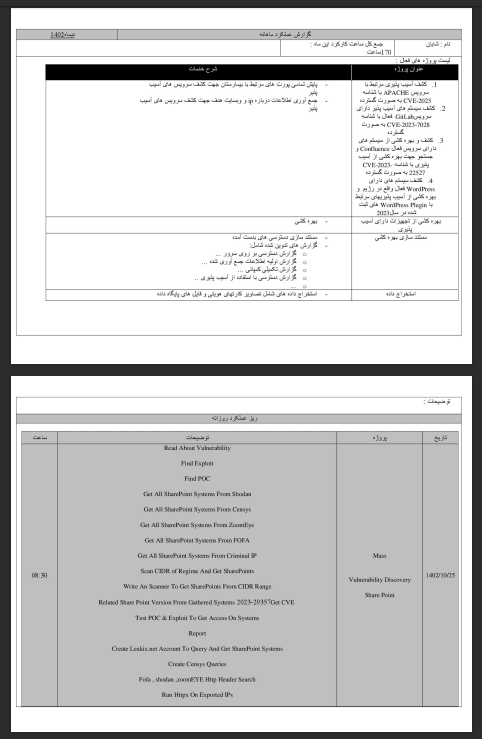

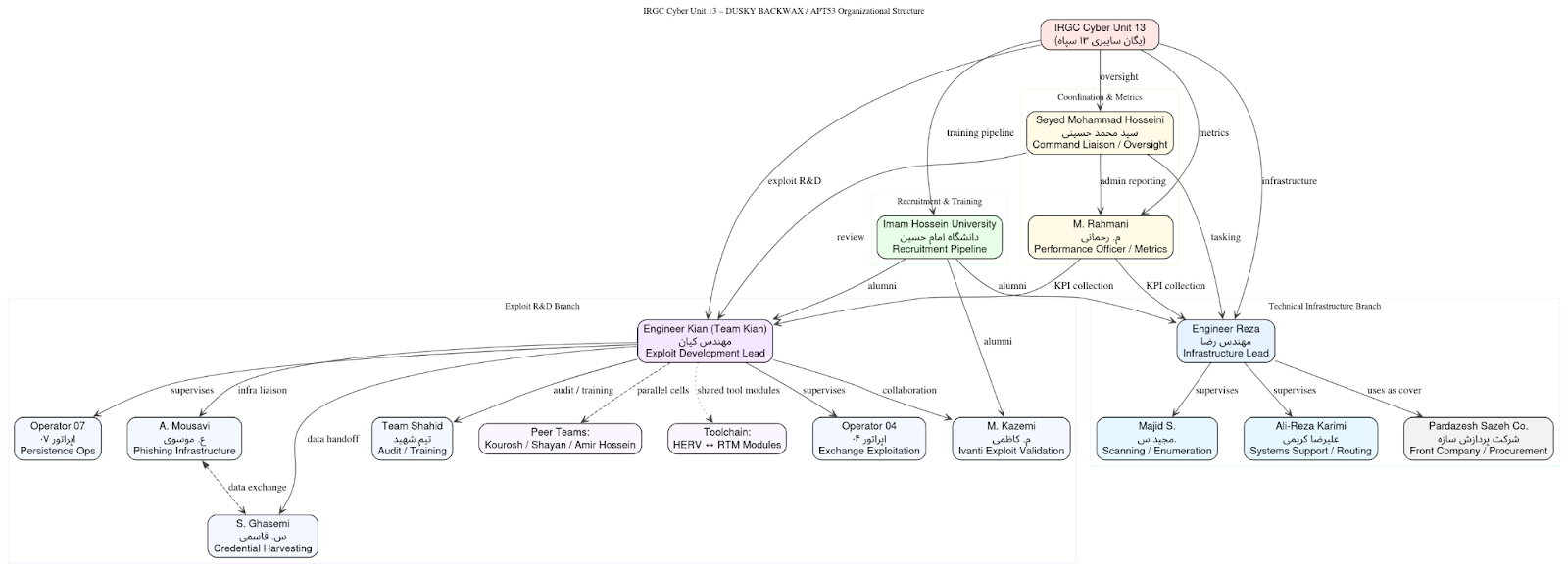

Organizational Structure & Command Hierarchy

The leaked materials reveal a structured command architecture rather than a decentralized hacking collective, an organization with distinct hierarchies, performance oversight, and bureaucratic discipline. Across the translated Farsi reports, KPI tables, and personnel documentation (including the entry_exit_form.pdf and the 1403, series operator reports), the same formalized layout repeats: a tasked cyber-intelligence regiment operating under the supervision of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Intelligence Organization (IRGC, IO).

Command and Oversight

At the apex sits the Campaign Coordination Unit, responsible for issuing daily directives, assigning operational quotas, and approving mission scopes. These coordinators function as the managerial arm of the IRGC IO cyber wing, translating strategic intelligence requirements, diplomatic collection, political influence, or economic mapping into discrete, trackable campaigns. Each campaign corresponds to a named lead analyst, who oversees operational sub teams tasked with exploitation, credential harvesting, phishing operations, and real time mailbox monitoring (RTM).

The hierarchy extends downward into operator cells, each specializing in a technical domain:

- Exploit Development Team weaponizing Ivanti, ProxyShell, and PowerShell chains into reusable scripts and RCE playbooks.

- Credential and Access Team conducting LSASS dumps, token replay, and OAuth abuse for persistence.

- HERV (HERV – Human Engineering and Remote Validation ) Phishing Unit refining HTML templates, MFA, bypass techniques, and KPI, driven lure campaigns.

- RTM and HUMINT Liaison Team monitoring compromised mailboxes, tagging “HIGH, VALUE” accounts, and routing intelligence to human analysts for contextual exploitation.

Supervisors in each unit aggregate performance data into standardized “daily performance tables”, measuring metrics such as tasks completed, credential yields, efficiency rate, and dwell time. Every operator signs their report, while supervisors annotate performance with remarks like “approved,” “escalate to analysis,” or “retrain on template variance.” These records, when viewed sequentially, function like military after action reports: formalized, evaluated, and subject to review by higher command.

Physical Centralization and Attendance

The entry and exit forms corroborate that these operators work from a centralized, secured facility. Each badge entry corresponds to the same personnel named in operational documents, confirming an on premises command center rather than a remote contractor model. Time-In/Time-Outlogs align precisely with the timestamps of phishing campaigns and Exchange exploitation bursts, implying synchronized shifts and supervised execution windows. Badge identifiers visible in the uploaded imagery show IRGC-affiliated institutional branding, likely part of a controlled government or contractor complex used for joint HUMINT–SIGINT operations.

Bureaucratic Culture and Chain of Custody

The bureaucratic tone of these documents suggests a military style rhythm of accountability: operators submit, supervisors validate, analysts escalate, and coordinators report upward to IRGC IO command. Even internal communications reflect hierarchical addresses, operators refer to superiors by title, reports are formatted in identical templates, and comments reference “efficiency improvements” and “mission adherence.” The precision of this structure transforms what might otherwise appear as scattered cyber incidents into a reproducible intelligence pipeline governed by measurable output.

In sum, the hierarchy revealed by these materials depicts a state run intelligence apparatus organized as a production line of cyber espionage. The structure mirrors conventional IRGC command principles, with centralized oversight, delegated specialization, and performance accountability all adapted to the digital domain. This is not a loose network of freelancers; it is a regimented institution whose workflows, personnel controls, and managerial review cycles directly mirror those of Iran’s established military and intelligence bureaucracy.

Personnel and Organizational Structure

The personnel and structural data contained within the APT35 corpus illustrates an institutionalized hierarchy typical of Iranian state cyber units operating under the broader IRGC umbrella. Across the extracted monthly performance reports (بهمن ماه) and campaign summaries, personnel are consistently listed by engineering title, operational alias, or numeric identifier. The pattern mirrors internal Iranian defense-sector bureaucracies, where formalized role tracking, quota systems, and hierarchical reporting enable central oversight of technical operations.

Rather than a loose federation of contractors, the materials depict a workforce of salaried operators functioning inside a command-and-control bureaucracy. Monthly reports are logged, audited, and annotated by supervisors. Personnel are reviewed on exploit deployment speed, data exfiltration success, and compliance with tasking instructions.

Identified Personnel and Operational Handles

Command and Operational Oversight

At the apex of the structure stands Abbas Rahrovi (عباس راهروی) also known as Abbas Hosseini, an IRGC-affiliated official responsible for creating and managing a network of front companies that serve as the administrative and technical cover for ongoing cyber-espionage campaigns. Under Rahrovi’s direction, this advanced persistent threat (APT) group has conducted offensive operations targeting telecommunications, aviation, and intelligence sectors across the Middle East and Gulf region, including Türkiye, the UAE, Qatar, Afghanistan, Israel, and Jordan.

Structural Hierarchy and Subordinate Cells

Within this organization, Vosoughi Niri (وثوقی نیری)) appears as a mid-to-senior-level coordinator tied to Rahrovi’s enterprise layer. Based on the corroborative evidence and document formatting observed in the uploaded “گزارش عملکرد ماهانه” (monthly performance reports), Niri likely fulfills a technical-administrative liaison role bridging field operators and the supervisory cadre. His name surfaces in contextual alignment with sections discussing efficiency optimization, task validation, and mission-adherence feedback loops, suggesting direct involvement in performance oversight and workflow standardization, hallmarks of IRGC command doctrine.

Niri’s placement within Rahrovi’s command hierarchy mirrors the IRGC’s hybrid intelligence model: a centralized leadership overseeing functionally specialized cells. Each cell reports through uniform reporting templates, reinforcing an internal culture of quantifiable accountability and military-style chain of command.

Activities and Counter-Intelligence Mandate

Operating under the guidance of the IRGC Counterintelligence Division, Rahrovi’s APT has expanded its mission set beyond foreign espionage. Internal communications and extracted documents show domestic surveillance of Iranian nationals deemed “regime opponents,” both inside and outside Iran. This dual focus, external intelligence collection and internal repression, typifies Iran’s fusion of SIGINT and HUMINT operations, where cyber units act as both offensive tools abroad and internal security enforcers at home.

Evidentiary Data from Dump

The exposure of this network is underpinned by an extensive evidentiary chain, including:

- Official IRGC-linked documents retrieved from the APT’s internal network;

- Personnel imagery correlating individuals to specific operations;

- Attack and target reports indicating clear tasking cycles;

- Translation and analysis documents reflecting multilingual target exploitation;

- Chat logs from internal communications tools such as Issabelle, 3CX, and Output Messenger — all of which validate the group’s internal coordination, task assignment, and reporting cadence.

Collectively, these findings dismantle any plausible deniability the actors once held under the IRGC’s institutional cover. The discovery of structured managerial oversight, including figures such as Rahrovi and Vosoughi Niri, demonstrates that these are not freelance cybercriminals but state-directed operatives functioning within a bureaucratized intelligence apparatus engineered for persistence, precision, and deniable control.

Operators:

Within the dump, nineteen ID badges were found from a conference in Iran on Israel. The conference badges titled “Israel: The Fragile Mirror” («اسرائیل آینه شکننده») adds a rare human dimension to the dataset, linking technical operators, long attributed to Iranian cyberespionage activity, with physical attendance at a domestic ideological event. This conference, held in multiple sessions across 2023 and organized under the banner of Sahyoun24 and affiliated cultural-security institutes, functioned as both a propaganda symposium and an analytic forum on Israel’s strategic vulnerabilities. The theme, “Israel as a fragile mirror reflecting its own internal divisions, social decay, and geopolitical exhaustion”, was a deliberate rhetorical inversion of Israeli intelligence narratives about Iran. Official writeups describe panels on psychological warfare, media confrontation, and “the post-Zionist collapse of social cohesion.” It was hosted in Tehran’s Baq Museum of Sacred Defense (باغ موزه دفاع مقدس), a location symbolically linked to the IRGC’s self-image as the custodian of revolutionary defense.

The badges of fifteen named individuals carrying sequential registration numbers and standardized QR codes were recovered from the operator dump, demonstrating that this was not merely a propaganda event but a managed, security-community gathering. The attendees listed (Norouzi, Sharifi, Hatami, Mousavi, Najafi, Nasimi, and others) correspond to the same internal communications clusters and device traces identified in the APT35 material. The overlap in formatting, file naming conventions, and local storage directories within the leak shows these badges were archived as part of the operators’ personal documentation, suggesting the attendees were members or affiliates of the same IRGC-linked technical units responsible for the Exchange exploitation campaigns detailed elsewhere in this corpus.

Within that operational ecosystem, attendance at Israel: The Fragile Mirror served several functions. First, it anchored the ideological justification for the group’s cyber campaigns, recasting intrusion and information theft not as espionage but as “defensive jihad” in the cognitive domain. Second, such conferences acted as recruitment and networking venues, where media officers, technical specialists, and propaganda units under the IRGC Cultural-Cyber Directorate intersected. These in-person sessions likely reinforced cross-unit collaboration between the operators running phishing and Exchange intrusion operations and those producing disinformation content targeting Israeli, Gulf, and Western media audiences.

The event’s agenda, particularly, the focus on psychological war, Zionist information operations, and digital sovereignty, mirrors the tactical doctrine embodied in APT35’s campaigns. The same operators photographed at or registered for the conference later executed targeted phishing and credential-theft operations using Israeli and Western diplomatic pretexts. The ideological framing provided by “The Fragile Mirror” conference positioned such cyber activity as a counter-narrative exercise: undermining adversary morale and exploiting perceived divisions within Israeli society. This linkage between cultural programming and operational tasking illustrates how Iran’s cyber apparatus merges soft-power indoctrination with offensive tradecraft, training its personnel to view digital espionage as a continuation of psychological warfare by other means.

In practical terms, the conference provided a semi-official aegis through which cyber operators could travel, convene, and exchange intelligence under the cover of academic or cultural engagement, consistent with IRGC and Ministry of Intelligence patterns observed since 2018. The badges’ sequential numbering and uniform QR encoding suggest centralized registration and identity management, potentially through the same administrative offices that coordinate the Thaqeb and Saqar technical institutes linked in prior datasets. By contextualizing APT35’s technical output within this ideological environment, the evidence affirms that their cyber operations are not rogue initiatives but state-aligned, bureaucratically normalized activities rooted in a shared worldview promoted through sanctioned events like “Israel: The Fragile Mirror.”

In sum, the conference stands as a bridge between rhetoric and operation: a physical manifestation of the belief system that animates APT35’s cyber doctrine. The operators who coded malware and exfiltrated credentials from foreign ministries also attended lectures on the “collapse of the Zionist regime.” Their presence at this event underscores that the Iranian state’s cyber units are not detached technologists but ideologically socialized cadres, trained simultaneously in faith, propaganda, and digital warfare.

The internal documentation reveals a structured ecosystem of named and numbered operators functioning under a disciplined command hierarchy. Personnel are consistently identified by a mix of professional titles, initials, and numeric designations, reflecting both bureaucratic formality and operational compartmentalization. Each name corresponds to a defined functional lane – engineering, exploitation, analytics, or administration — suggesting a deliberate division of labor designed to ensure continuity and accountability across campaigns. The repeated use of the honorific “Engineer” (مهندس) underscores the technical stature and formal employment status of several individuals, while numeric “Operator” tags indicate pseudonymous, task-based identities. Collectively, these records demonstrate that the unit operates as an organized workforce rather than an ad hoc hacker collective, with performance tracked, reviewed, and signed off by supervisors in a manner analogous to military or intelligence command structures.

Engineer Reza (مهندس رضا)

Referenced repeatedly as a technical lead overseeing infrastructure maintenance and deployment of Exchange-based exploits. Reza’s name appears in at least two separate performance reports, tied to scanning operations and uptime monitoring. Contextual indicators suggest a mid-level managerial role coordinating sub-teams responsible for access maintenance.

Engineer Kian (مهندس کیان)

Appears as a senior analyst or supervisor. The phrase “Team Kian” (تیم کیان) is used interchangeably with his name, implying that Kian manages a discrete operator cell. His team’s metrics emphasize exploit refinement, suggesting a focus on post-exploitation tooling and persistence.

Majid S. (مجید س.)

Associated with enumeration, lateral movement, and network scanning. The format of his report entries mirrors those of technical specialists who handle discovery and mapping of vulnerable services.

Seyed Mohammad Hosseini (سید محمد حسینی)

Mentioned in several analytic summaries, typically in administrative or oversight roles. Context implies he acts as an internal liaison between operational units and upper command.

Ali-Reza Karimi (علیرضا کریمی)

Described in the context of systems support and network configuration. Karimi’s work aligns with internal infrastructure maintenance and possibly VPN routing within Iranian ISP space.

M. Rahmani (م. رحمانی)

Appears in the monthly KPI spreadsheets as a performance tracker and reporting officer. His role appears clerical but critical — he consolidates operator statistics into higher-order analytic reports for command review, functioning as an internal metrics analyst.

Operator 04 / Operator 07 (اپراتور ۰۴ / اپراتور ۰۷)

Numeric identifiers tied to Exchange exploitation operations. Each “operator” designation corresponds to a unique user within the log corpus, implying either pseudonymous staff accounts or task-specific credential sets. Operator 04 is repeatedly observed in May–June 2022 Exchange exploitation records; Operator 07 appears in follow-on persistence activity.

Team Shahid (تیم شهید)

Referenced as an auditing or training subdivision, possibly connected to internal quality control. The term Shahid (شهید – martyr) is frequently used in Iranian military nomenclature for units named after fallen personnel.

Technical and Exploit-Focused Personnel

M. Kazemi (م. کاظمی)

Appears in Ivanti Connect Secure exploitation testing notes. Kazemi’s entries involve patch verification and vulnerability regression checks, indicative of a red-team engineering role tasked with exploit validation.

A. Mousavi (ع. موسوی)

Named in the phishing-infrastructure section, likely responsible for domain registration and control of operational mail servers. Mousavi’s profile suggests a hybrid technical–operational role bridging the gap between social engineering campaigns and backend infrastructure.

S. Ghasemi (س. قاسمی)

Connected to credential-harvesting playbooks and exfiltration scripts. Ghasemi’s responsibilities likely include automation of credential capture pipelines and data normalization for reporting.

Organizational and Institutional Context

IRGC Cyber Unit 13 (یگان سایبری ۱۳ سپاه پاسداران انقلاب اسلامی)

The structural relationship between APT35 and Unit 13 aligns with known IRGC cyber-force command chains, where Unit 13 functions as the technical backbone supporting both offensive operations and defensive R&D.

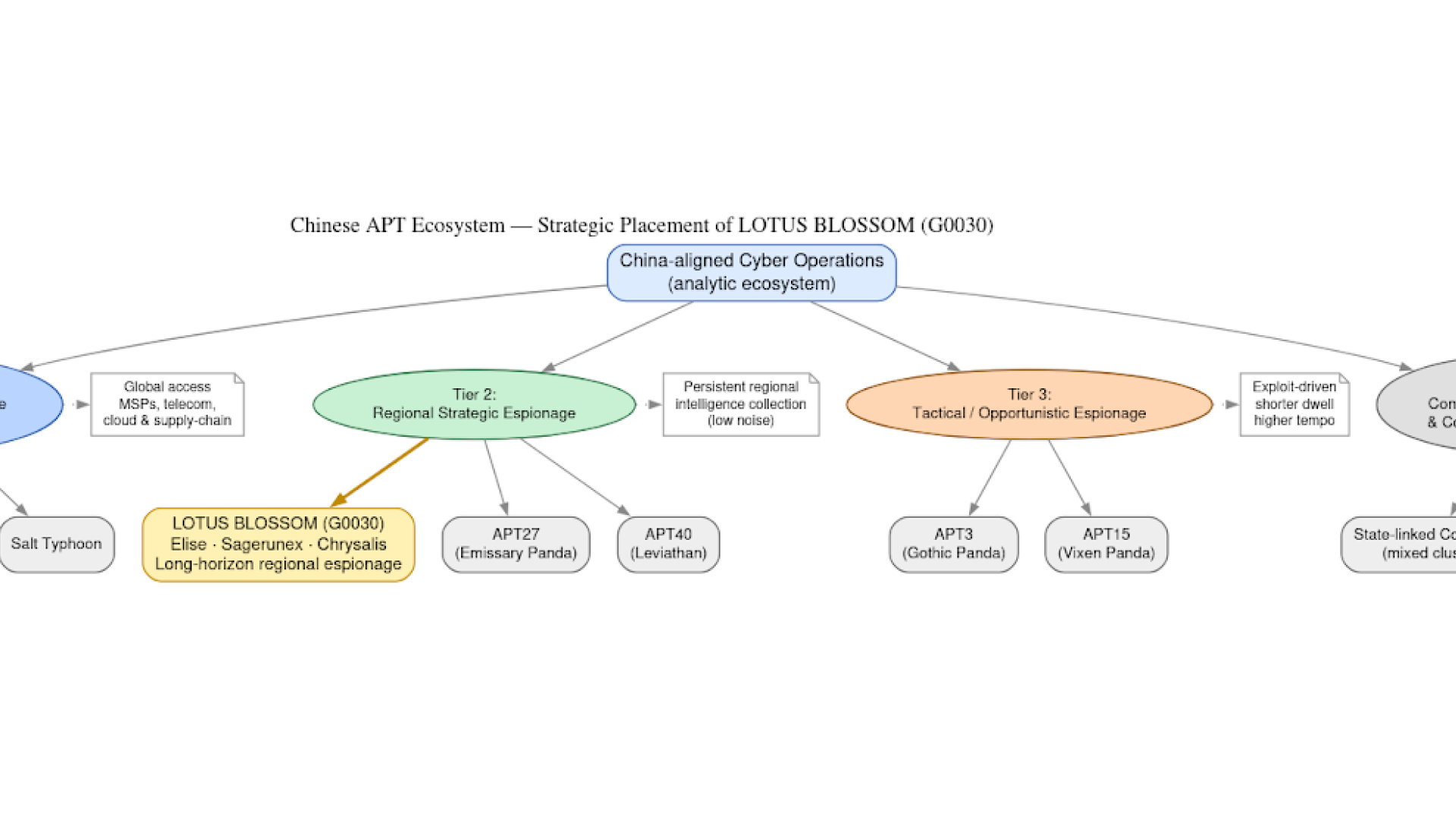

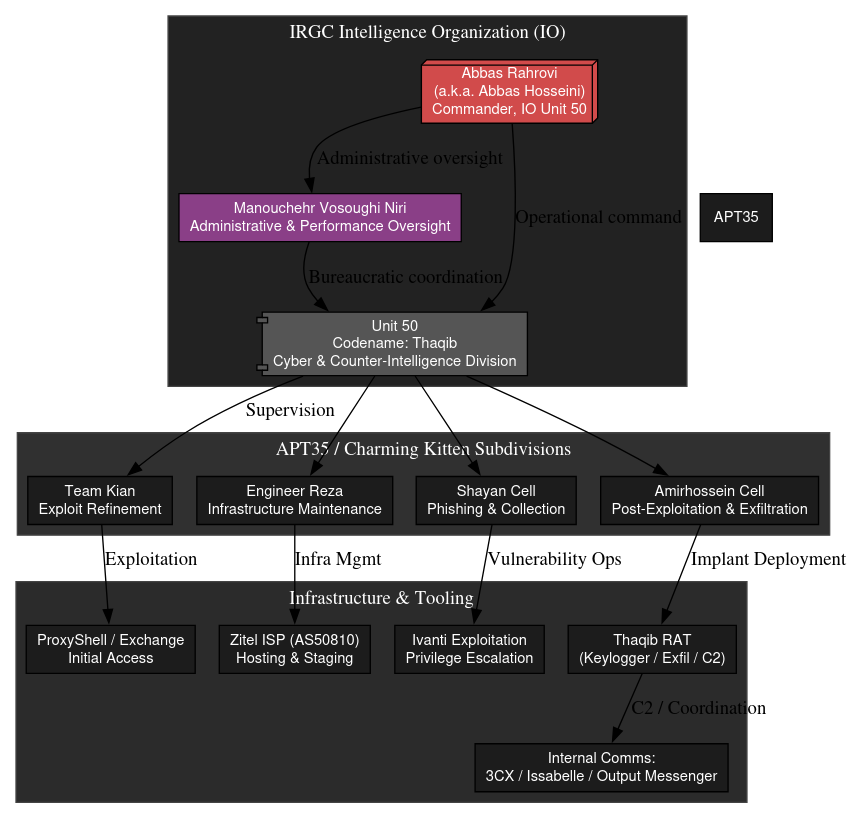

Structural Convergence: IRGC IO Unit 50, APT35, and the Integrated Command Apparatus

The recent exposure of IRGC Intelligence Organization (IO) Unit 50, internally codenamed “Thaqib,” completes the organizational puzzle long inferred from the APT35/Charming Kitten document set. Unit 50 represents the institutional fusion of Iran’s technical intrusion directorates and psychological-operations elements, revealing how bureaucratic oversight, cyber-espionage, and counter-intelligence are integrated within the IRGC’s command ecosystem.

At the top of this structure stands Abbas Rahrovi (aka Abbas Hosseini), identified as a senior IO-IRGC cyber command authority. Rahrovi’s role — confirmed through invoices, personnel files, and operational correspondence from internal program material — parallels the “senior coordinator” function described in APT35’s internal performance reports. His control over front companies, including entities such as Andishan Tafakor Sefid (“White Thought Depths”), provides the administrative façade through which APT operators receive compensation, assignments, and task metrics, erasing the divide between military and civilian employment.

Beneath Rahrovi, Manouchehr Vosoughi Niri emerges as an administrative signatory and performance-management officer. His name on employment and operational records corresponds directly to the managerial language and template uniformity seen in the monthly performance reports (گزارش عملکرد ماهانه) recovered from the APT35 leak. Identical phrasing, “efficiency improvements,” “mission adherence,” “task verification”, and the standardized tabulation of operator hours indicate that Niri’s office served as the bureaucratic bridge between technical operators and IRGC leadership. The same hierarchy present in those internal Farsi reports — operator → supervisor → coordinator → command — appears in Unit 50 under Rahrovi, confirming that APT35’s workflow was embedded within IO-IRGC’s institutional chain of command.

On the technical side, the Thaqib RAT associated with Unit 50 represents the evolutionary successor to the Ivanti and ProxyShell exploitation workflows documented in the APT35 corpus. Both rely on identical tradecraft: phishing and supply-chain compromise for initial access, PowerShell-based persistence, credential theft, and staged exfiltration through controlled Iranian ISPs, particularly Zitel (AS50810), which also appears in the analyzed access-log dataset. The shared tool lineage and infrastructure reveal a unified development pipeline maintained under IO-IRGC supervision, with Unit 50 serving as the engineering and operational nucleus for multiple outward-facing APT teams.

Operationally, the overlap extends beyond technical objectives. Unit 50’s dual mandate—to conduct external espionage against regional and Western targets while monitoring domestic dissidents, mirrors APT35’s known blending of HUMINT, SIGINT, and influence operations. The recovered references to internal collaboration platforms (3CX, Issabelle, Output Messenger) further confirm a shared communications ecosystem coordinating campaigns across both “Thaqib” and APT35 workstreams.

Taken together, the evidence demonstrates that APT35 is not an isolated threat actor but a subordinate subdivision of IRGC IO Unit 50, reporting through Rahrovi’s command cell and administered by Vosoughi Niri’s office. The internal monthly reports, program artifacts, and infrastructure telemetry form a continuous evidentiary chain depicting a single, state-run enterprise that unites technical intrusion, information operations, and domestic counter-intelligence under one command architecture. What were once categorized as discrete clusters – APT35, Charming Kitten, Phosphorus – are in practice, modular teams within the IRGC IO cyber-espionage production line overseen by Unit 50.

Network and Target Infrastructure References

A recurring set of international IP addresses appear in associated logs, reflecting both operational relay points and foreign targets. These address patterns confirm that APT35 leveraged both domestic ISPs (for staging) and international IP space (for target access), maintaining operational separation through regionally diverse infrastructure.

Campaign and Codename Taxonomy

- APT35 umbrella codename for the leaked corpus, representing the internal reporting and exploit-management environment of APT35.

- Operation Kourosh, Operation Shayan, Operation Amir Hossein — likely internal monthly or operator-specific codenames correlating to بهمن ماه performance cycles.

- Campaign Jordan (کمپین جردن) — externally oriented operation directed at Middle Eastern targets; cross-references suggest the campaign focused on government and telecom entities.

Operational Analytic Assessment

The recurring personnel patterns, structured performance tracking, and formalized hierarchy reinforce that APT35 represents a bureaucratically managed, state-directed offensive-cyber enterprise. Personnel titles and engineering designations mirror those of Iranian defense-sector agencies, indicating that operations were executed under institutional oversight rather than freelance initiative.

The integration of clerical, technical, and managerial functions (e.g., Rahmani’s metrics tracking, Reza’s technical supervision, Kian’s team leadership) demonstrates an intelligence organization where success is quantitatively measured and tightly supervised. The presence of formal education affiliations (Imam Hossein University) and front companies (Pardazesh Sazeh Co.) further corroborate IRGC influence.

This structure enables Iran’s cyber apparatus to align day-to-day operational output with strategic intelligence objectives, monitoring adversary communications, maintaining regional situational awareness, and ensuring persistent visibility into diplomatic and infrastructure networks across the Middle East and Asia.

Operational Themes

The documentation depicts a tightly governed system in which every operator adheres to a uniform reporting template rather than ad hoc notes. Each form records standardized metrics, tasks completed, efficiency rate, and supervisor remarks, transforming individual actions into quantifiable performance data. This bureaucratic structure allows supervisors to rank, reassign, and reward personnel, effectively turning the template into a scorecard that enforces consistency, auditability, and disciplined, repeatable behavior over opportunistic freelancing.

Reconnaissance is explicitly dual-mode. At scale, the unit runs internet-wide discovery, broad scanning to map services, identifies exposed endpoints, and prioritizes classes of vulnerable software. Those mass recon passes are then refined into country and sector-specific hit lists: curated ProxyShell target sets, prioritized Exchange estates, and hand-picked hosts for manual exploitation. The result is a funnel, producing high-value target queues tailored to regional objectives.

The collection is Exchange-centric by design. The group weaponizes Exchange attack chains (ProxyShell, Autodiscover, EWS enumeration, and PowerShell driven tasks) to extract mailbox contents and Global Address Lists. Those artifacts serve as both intelligence and infrastructure: GALs seed phishing lists; mailboxes become long, running HUMINT sensors; harvested messages reveal follow-on targets and operational context.

Meanwhile, persistence is credential-driven. Memory and token theft tools (Mimikatz style dumps), automated token-replay, and abuse of delegated OAuth flows are used to convert initial access into sustainable footholds. Rather than relying solely on fragile webshells, the operators bake credential reuse and token persistence into their lifecycle, enabling repeated access even as individual hosts are remediated.

Finally, exploitation and social engineering are integrated into a closed loop. HERV-style phishing operations generate credentials that feed the exploitation teams; compromised mailboxes both validate access and produce fresh lures and contact lists.This creates a self-sustaining cycle where reconnaissance, exploitation, credential harvesting, and phishing continuously replenish each other under programmatic control.

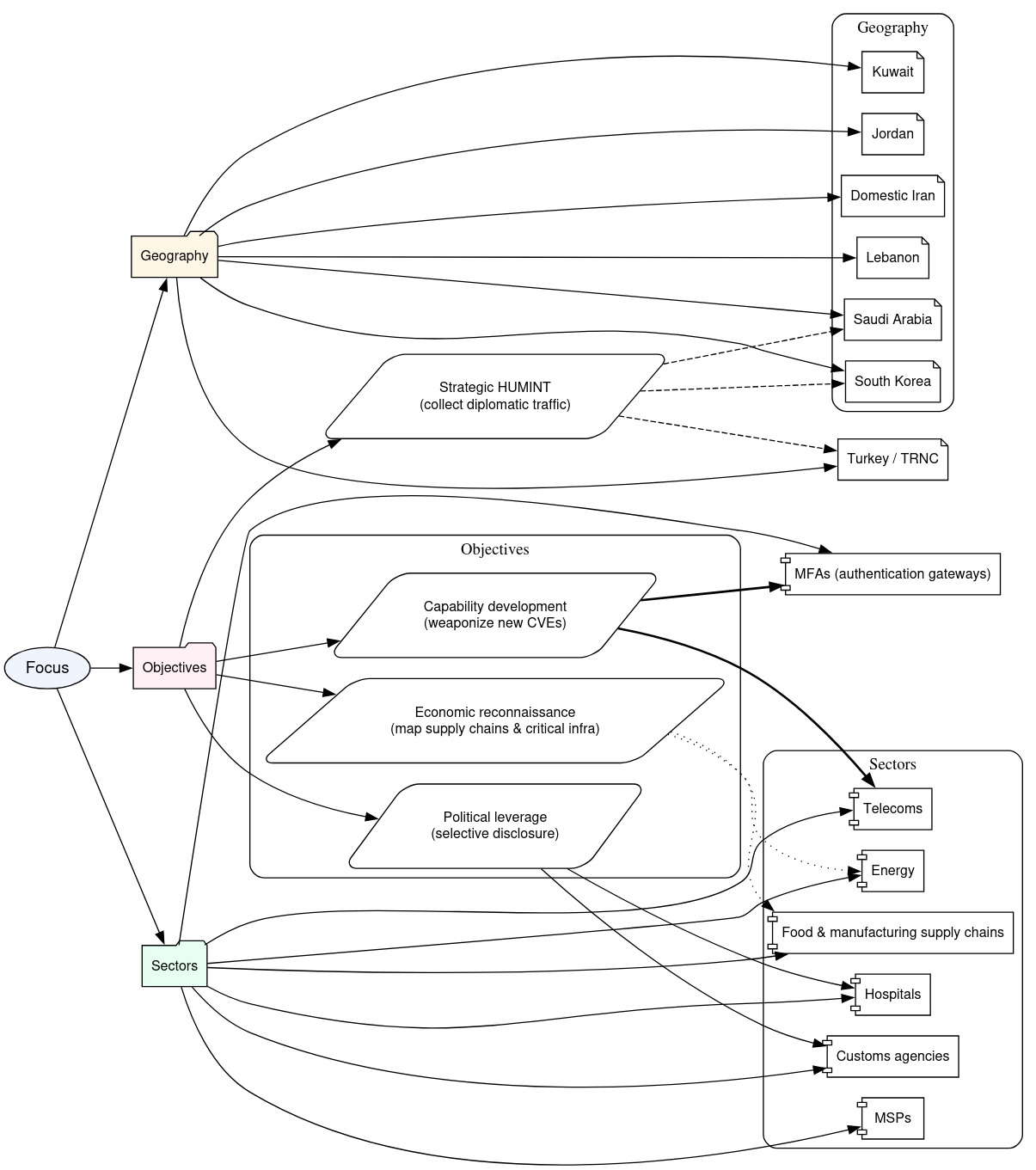

Geopolitics of Targeting & Campaign Goals

Focus and observed objectives across the dataset point to a strategically targeted, region wide intelligence effort rather than random opportunism. The geographic footprint centers on Türkiye, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), Lebanon, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, South Korea, and domestic Iranian targets, with operations tailored to each locale’s political and technical landscape. Sector selection repeatedly favors high value collection points, multifactor authentication gateways, customs agencies, telecom operators, energy firms, hospitals, managed service providers, and food and manufacturing supply chains, all places where access yields both operational intelligence and strategic leverage.

The group’s operational goals are explicit and multi-layered. First, strategic HUMINT focuses on sustained mailbox monitoring and GAL exploitation to collect diplomatic traffic and internal communications. Second, political leverage comes from selective disclosure and escalation of sensitive material as a coercive tool. Third, economic reconnaissance aims to map supply chains and critical infrastructure to inform targeting and potential future operations. Fourth, capability development is achieved by actively weaponizing newly disclosed CVEs and codifying those techniques into repeatable playbooks. Together, these focus areas describe an actor prioritizing persistent intelligence collection, influence, and the continuous maturation of offensive capabilities.

Intent Analysis by Targeted Entity

Across the documented campaigns, the unit’s intent mirrors a clear, target-specific calculus. Against government and critical-infrastructure organizations the objective is sustained intelligence collection and long-term access for strategic exploitation. With large commercial and telecommunications providers the focus shifts to credential harvest and lateral pivoting to upstream customers and partners, and against small-to-medium regional targets the operations emphasize scalable account takeover and data harvesting to build volume for broader campaigns. This prioritization, guided by centralized tasking and KPI-driven workplans, reflects an operational doctrine that values persistent footholds, credential multiplicity, and the ability to trade discreet access for wider network advantage.

Türkiye: Türk Telekom (212.175.168.58)

Observed activity: Exchange-centric intrusion attempts, credential harvesting funnels (GAL → HERV), persistent access scripts validated by Team Kian.

Likely intent:

- Regional situational awareness: Turkish government and critical telecom routing are high-value for monitoring regional politics, Syria/Iraq corridors, and NATO-adjacent traffic.

- Negotiation leverage: Access to telco mail flows yields insight into lawful intercept requests, roaming agreements, and government guidance to carriers.

- Access brokerage: Telco footholds enable pivoting into downstream enterprise customers.

- Why this entity matters: A national carrier concentrates VIP communications, roaming metadata, and cross-border peering visibility—rich for SIGINT and target development.

- Confidence: High (KPI alignment + Exchange/persistence emphasis).

Saudi Arabia: Nour Communication Co. Ltd (212.12.178.178)

Observed activity: Phishing infrastructure mapped to credential theft, mailbox rule creation, and RTM tagging (“HIGH,” “VALUE”).

Likely intent:

- Energy/diplomatic visibility: Follow Saudi policy and energy sector signals; anticipate negotiation positions in OPEC+, Yemen, and U.S. relations.

- Target discovery: Enumerate subsidiary and hosted customer estates for second-order exploitation.

- Narrative operations support: Email insight can enable selective leaks, timing-based influence, or coercive messaging.

- Why this entity matters: Saudi carriers and service providers sit at the core of GCC communications.

- Confidence: Medium-High (campaign notes + phishing/HERV handoffs).

Kuwait: Fast Communication Company Ltd (83.96.77.227)

Observed activity: Exchange account intrusion attempts, post-exploitation tooling validation, credential collection.

Likely intent:

- GCC situational awareness: Track policy alignments, defense procurement, and oil/gas logistics.

- Regional pivot: Use Kuwaiti access to identify shared vendors and managed-service footholds into neighboring ministries and SOEs.

- Why this entity matters: Smaller state telecom/hosting providers can be stepping stones into ministries and national oil entities.

- Confidence: Medium (campaign references + shared TTPs).

South Korea: IRT-KRNIC-KR (1.235.222.140)

Observed activity: Mailbox targeting, GAL export attempts, and KPI-tracked follow-ons.

Likely intent:

- Tech and defense intelligence: Seek bidirectional visibility into R&D, export controls, and defense supply chains.

- Crisis exploitation: Maintain latent access to leverage during peninsular or sanctions crises; harvest identity data for later impersonation.

- Why this entity matters: KR provides high-value technology intel and alliance perspective; access to registries and service operators unlocks broad enumerations.

- Confidence: Medium (entity class + Exchange workflow alignment).

Türkiye/Jordan Campaign Overlap: “Campaign Jordan (کمپین جردن)”

Observed activity: Use of Team Kian’s persistence scripts in field ops, coordinated phishing and credential harvest, Exchange post-exploitation.

Likely intent:

- Government and diplomatic monitoring: Track Jordan’s security cooperation, refugee policy, and regional coordination with KSA/UAE/Egypt.

- Transit node mapping: Identify cross-border data flows and hosting providers used by NGOs and government bodies.

- Confidence: Medium-High (direct campaign doc references to Team Kian tooling).

- Confidence: Medium-High (direct campaign doc references to Team Kian tooling).

Singapore RIPE hosted relay (128.199.237.132)

Observed activity: Operational relay / egress node, not a victim per se.

Likely intent:

- Operational security: Traffic laundering, geographic blending, and separation of staging from Iranian IP space.

- Latency and availability: Stable cloud region used to front C2 or scraping tasks.

- Why it matters: Indicates tradecraft maturity: clean separation of staging, collection, and command infrastructure.

- Confidence: High (infrastructure role is consistent across operations).

Iran (Domestic) Pishgaman Tejarat Sayar DSL Network (109.125.132.66)

Observed activity: Operator side usage; staging, internal VPN, or development/test access.

Likely intent:

- Operator base network: Workstation egress, internal tooling pulls, or QA against live targets.

- Why it matters: Provides vantage for timing analysis and potential legal/telecom cooperation to identify operator shifts.

- Confidence: High for “operator use,” not an “attacked entity.”

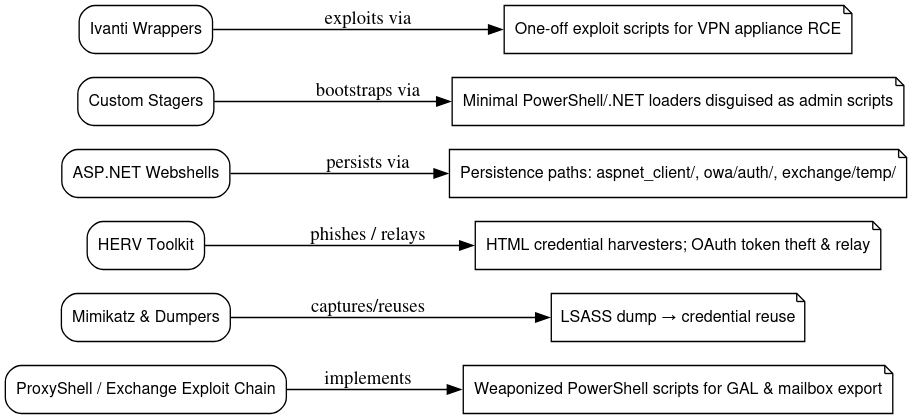

Toolset and Operational Practices

The internal reports, campaign post-mortems, and technical write-ups produced by the actor cluster we are tracking reveals a deliberate, repeatable toolchain optimized for large-scale, quota-driven compromise operations: broad, automated discovery; prioritized exploitation of enterprise mail and VPN appliances; rapid persistence and credential harvesting; covert exfiltration; and bureaucratic measurement of results. The tools are a mix of widely available offensive frameworks and bespoke utilities, tied together by standardized playbooks and KPI reporting. The unit’s posture is that of an operationally mature, state-directed cyber organization: methodical, adaptable, and focused on measurable throughput rather than opportunistic one-offs.

The actor operates a hardened, process-driven offensive stack centered on high-yield enterprise targets: Microsoft Exchange (ProxyShell/ProxyLogon exploit chains and automated ASPX/.NET webshell deployers), Ivanti/Pulse Secure and similar VPN appliance exploit kits, and application delivery controller (F5) modules used to bypass patched Exchange instances. Reconnaissance is performed at scale with Masscan/Nmap-style scanners wrapped in custom orchestration, internal “shodan-like” scanning platforms, and lightweight HTTP probes that look for exposed admin endpoints, .env files, and RDP fingerprints to feed prioritized target lists. Initial access is routinely followed by rapid persistence (ASPX webshells with HTTP beaconing, scheduled tasks, PowerShell and WMI lateral execution), credential harvesting (EWS/Exchange scraping scripts, HTML credential collectors from phishing kits, LSASS dumping via Mimikatz-style utilities), and MFA defeat techniques including token-relay/AiTM patterns and token replay. Post-exploitation tooling is a mixed ecosystem of .NET webshells, Python parsers packaged with PyInstaller, modified Cobalt Strike–like beacons, and bespoke Windows loaders; exfiltration channels include encrypted 7zip archives staged to cloud storage (Mega, Dropbox, ProtonDrive), SMTP/compromised Exchange relays, DNS tunneling, and custom HTTP C2 beacons, while Telegram bots and API scripts provide operational telemetry and KPI ingestion for centralized reporting.

Organizationally, the unit is bureaucratic and organized into specialized discrete cells for scanning (Engineer Reza), exploit refinement and persistence engineering (Team Kian), phishing and credential ops (Engineer Shayan), and data staging/reporting, which produces high throughput and rapid tooling iteration. Their operational doctrine blends commodity offensive frameworks with in-house wrappers and tailored obfuscation to blend malicious traffic into normal enterprise patterns including the use of legitimate cloud providers for staging, VPN chaining and consumer VPNs to mask operator origin, and careful phishing templates localized to target regions. Intelligence implications are severe: this is a resilient, state-tasked capability optimized for mass credential capture and long-term access. Immediate defensive priorities are clear: harden and monitor Exchange/EWS/OWA with focused logging and retention; patch and segment remote-access appliances (Ivanti, F5); enforce phishing-resistant MFA such as FIDO2; hunt for ASPX webshell signatures and anomalous LSASS dumps or scheduled tasks; and deploy detection rules for scanning patterns, token-relay behavior, and unusual cloud staging traffic to disrupt the adversary’s kill-chain and their KPI-driven feedback loop.

The leaked materials reveal more than tools and targets, they expose a bureaucratized workplace culture that governs operator behavior through rigid templates, quotas, and supervision. Standardized KPI forms, efficiency metrics, and supervisor remarks turn tradecraft into measurable output, pushing operators to prioritize volume, more lures, faster credential harvests, shorter dwell times, even at the cost of OPSEC. Specialization across exploit, credential, and phishing teams (e.g., HERV units) increases technical proficiency but also moral distance, framing each task as a detached contribution to a collective mission. Centralized attendance logs confirm a shared worksite where peer pressure, oversight, and managerial review reinforce compliance and suppress deviation. The result is a sociotechnical system that produces consistent behavioral signatures, template-based phishing, reused webshell paths, and uniform reporting rhythms. This makes the actor efficient yet predictable, and therefore exploitable once defenders understand its metrics and workflow.

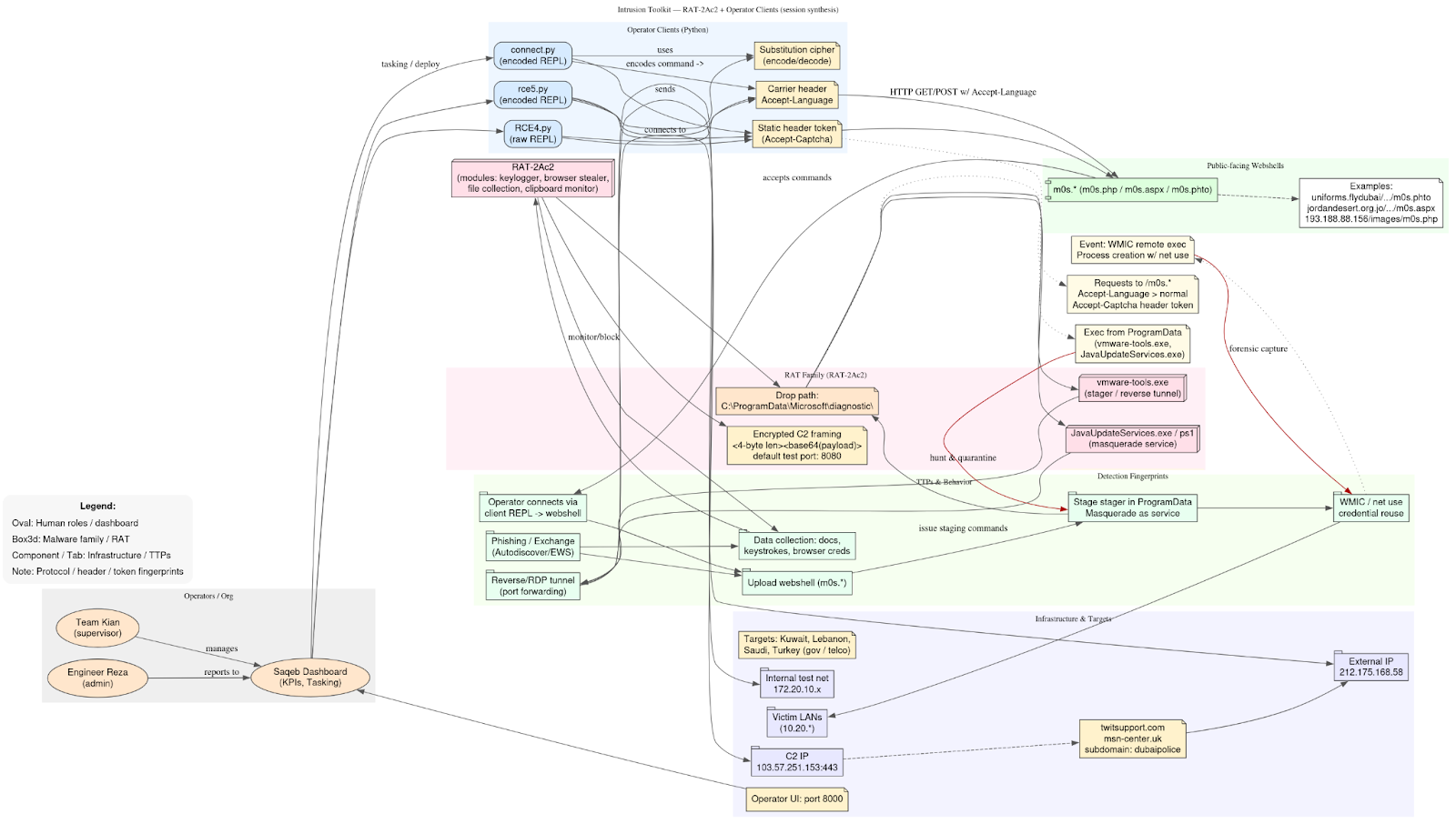

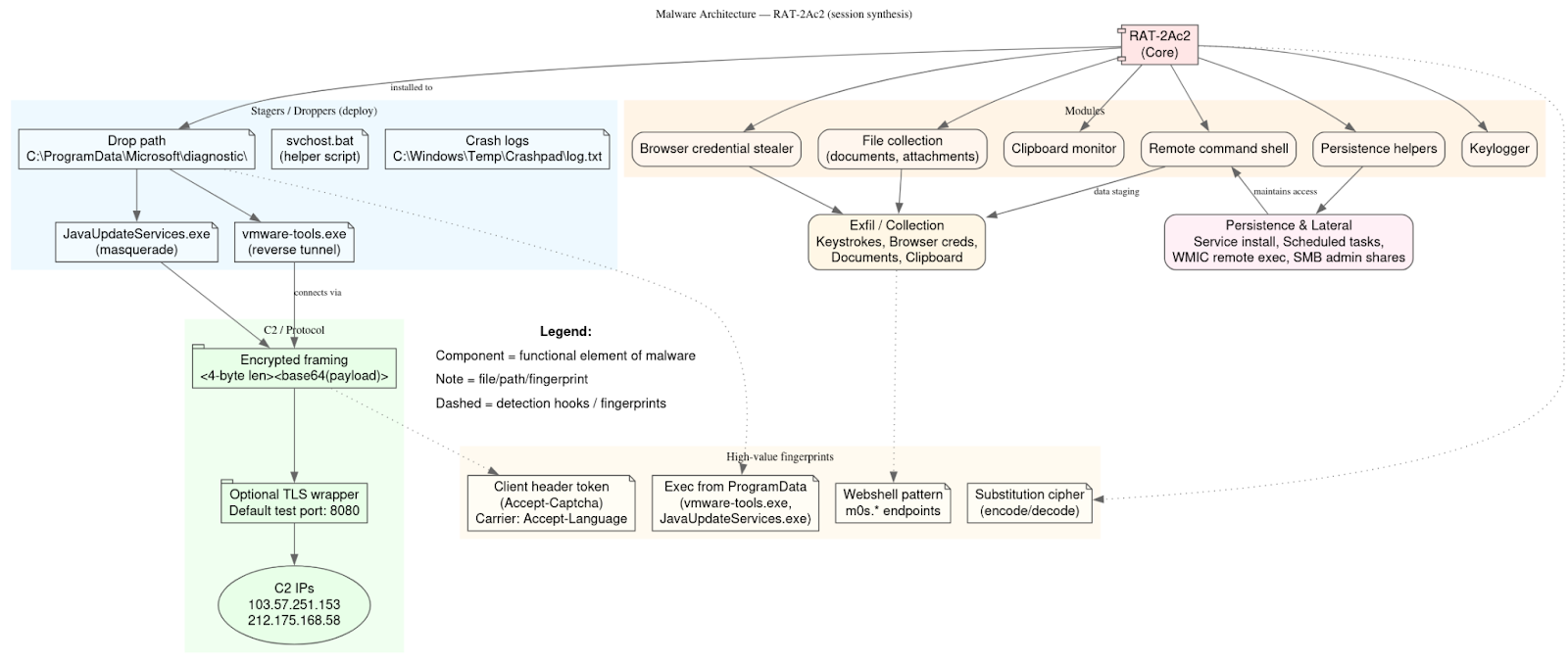

Malware Analysis

The uploaded data documents a mature, operator-driven intrusion toolkit built around two complementary components: a Windows-focused remote access trojan family (RAT-2Ac2 and associated stagers) used for persistence, credential theft, and data collection, and lightweight operator client tooling plus webshells that provide an interactive control channel for hands-on management of compromised systems. Evidence for the RAT, including developer notes describing modules for keylogging, browser credential theft, file collection, an encrypted length-prefixed command channel, and a canonical drop path under C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\diagnostic\ is present in the engineering reports and stager examples.

The client tooling is simple but operationally effective: multiple Python clients implement an interactive REPL that sends operator commands to server-side webshells by embedding the command inside an HTTP header (notably Accept-Language), accompanied by a static header token used by the operator clients as a handshake/fingerprint. Two clients use a fixed substitution cipher to obfuscate commands prior to transport, while another sends commands raw; all three hardcode different webshell endpoints and identical header fingerprints, showing reuse of the same control method across multiple targets.

Deployment and execution follow a consistent behavioral pattern. Initial access appears to rely on phishing and on Exchange/Autodiscover chains documented elsewhere in the corpus. Once an initial foothold exists, operators upload a webshell (commonly named using the m0s.* pattern), connect with the client, and issue commands to stage a more persistent artifact on internal hosts. Those artifacts are placed into ProgramData and masqueraded under plausible Windows service names (for example, Java/Update-style names or a vmware-tools.exe filename), then executed to create reverse tunnels or RDP-style connections back to external C2s. The operational control UI observed in the files constructs WMIC and net use commands programmatically, which the operator then dispatches to targeted hosts, enabling rapid lateral movement and hands-on exploitation.

From a capability perspective, the toolkit supports the full mid-stage lifecycle required for broad intrusions: credential harvesting and reuse, remote execution (WMIC, SMB admin share mounts), privilege persistence (service-style dropper placement), encrypted C2 with framing and optional TLS wrapping, and collection modules that capture documents, keystrokes, and browser-stored credentials. The presence of crash logging and developer guidance in the notes indicates an active development lifecycle and repeated testing in internal test ranges prior to production C2 rotation.

Operational fingerprints suitable for detection are clear and high-value. Host-level hunts should prioritize anomalous execution from ProgramData paths that mimic system services, the presence of vmware-tools.exe or JavaUpdateServices.exe under C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\diagnostic\, and svchost.bat helper scripts. Network and webserver detection should look for m0s.* endpoints and unusually long or non-language payloads in Accept-Language headers, and the static Accept-Captcha token string found in the client code, as that token provides an immediate, precise signature for operator traffic.

For containment and remediation, the priority actions are straightforward: treat any accounts and credentials observed in scripts as compromised and rotate them immediately, block outbound connectivity to identified C2 IPs and domains, and hunt for the ProgramData stager paths and web UI artifacts (including services masquerading under benign names and a local operator web UI typically served on port 8000 in these artifacts). When hosts are confirmed compromised, isolate and capture volatile memory, webserver logs, and disk images before remediation to preserve forensic evidence and enable robust reverse engineering of the stagers.

Confidence in the internal linkage across these artifacts is moderate to high. Multiple documents reuse the same linguistic style, operator names, filenames, and patterns, the dashboard and KPI tables reinforce an organizational, metrics-driven approach to operations, while the developer notes and client scripts reveal the technical underpinnings and the protocol choices operators relied upon. Taken together, the corpus points to an evolving, in-house capability that combines tailored RAT development with simple, reliable operator tooling and established operational tradecraft for lateral movement and persistence.

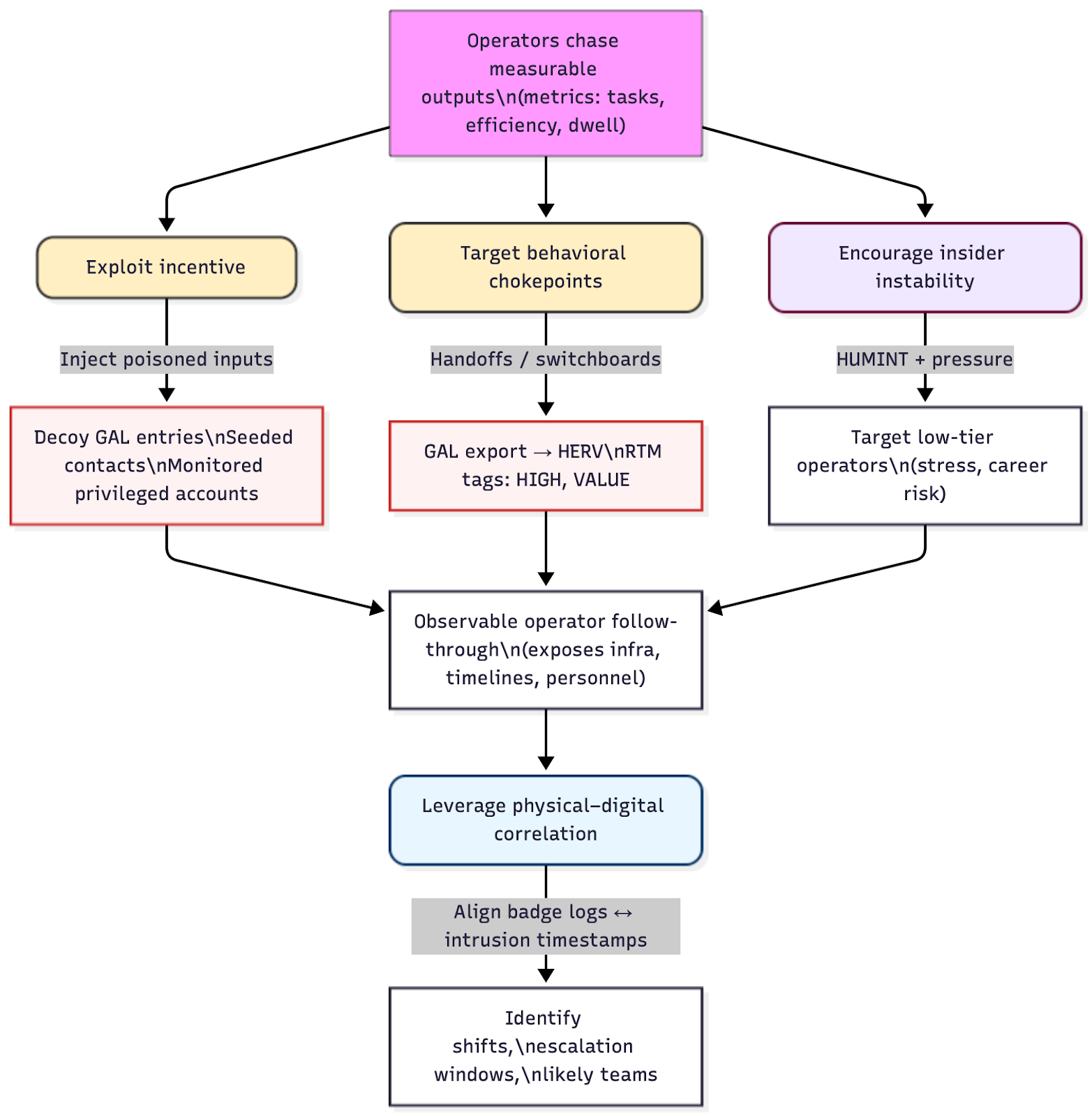

HUMINT & Counterintelligence Opportunities

The leaked materials reveal a bureaucratized ecosystem where structured templates, quotas, and supervision dictate operator behavior. Standardized KPI forms and supervisor annotations turn cyber operations into measurable output, tasks completed, efficiency rates, and quota attainment, pressuring personnel to maximize volume and speed at the expense of operational security. Highly specialized teams handle discrete phases of the attack chain, from exploit development to credential harvesting and HERV phishing, fostering technical proficiency but also moral distance from the consequences of their actions. Centralized attendance logs confirm an on-site workforce governed by peer norms and managerial oversight, reinforcing conformity and deterring dissent. Together, these dynamics produce a sociotechnical rhythm that makes the unit efficient, disciplined, and auditable, but also predictable, allowing defenders to anticipate and exploit recurring behavioral and procedural patterns.

The human-centered features of the operation create multiple pragmatic avenues for HUMINT and counterintelligence:

- Exploit incentive loops. Because operators chase measurable outputs, injecting false or poisoned inputs (e.g., decoy GAL entries, seeded contacts that lead to dead ends, plausibly privileged but monitored accounts) can produce observable follow-through that exposes infrastructure, timelines, or personnel.

- Target behavioral chokepoints. Handoffs (GAL export → HERV) and switchboards (RTM tags like “HIGH, VALUE”) are logical places to interpose deception or monitoring; a single tampered GAL can produce downstream intelligence on collection paths.

- Leverage physical–digital correlation. Aligning badge logs with intrusion timestamps can help identify likely shifts, escalation windows, and even the specific teams running a campaign, enabling tailored HUMINT or legal avenues of pressure.

- Encourage insider instability. Performance driven cultures generate internal stress. Well-crafted HUMINT approaches that emphasize career risk, poor performance, or the moral costs of operations can sometimes induce cooperation or mistakes, especially among lower tier operators who are most exposed to quota pressure.

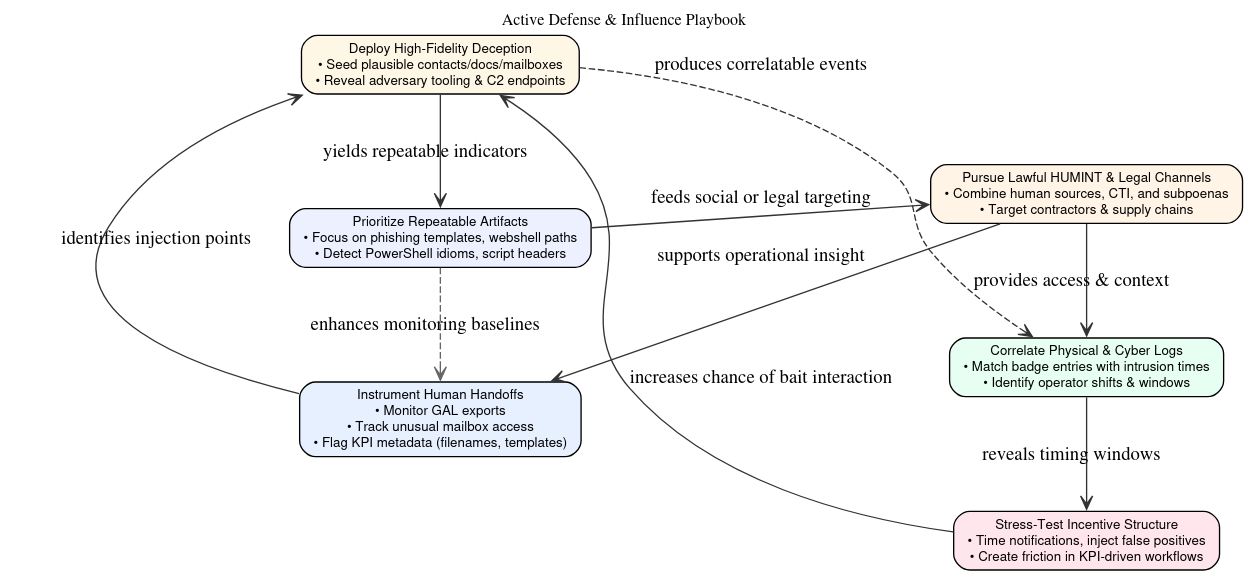

Defensive & Operational Recommendations (HUMINT aware)

For effective defense, it is crucial to instrument human handoffs and monitor the signals that travel between people and systems: alert on GAL exports, anomalous mailbox access patterns, and KPI workflow metadata (filenames, templates, and report stamps). At the same time, deploy high-fidelity deception, seed plausible contacts, documents, and mailbox content designed to make adversaries reveal tooling, extraction paths, or C2 when they act on the bait. Where lawful HUMINT or partner cooperation is available, correlate badge entry/exit logs with intrusion timestamps to map shifts and likely operator windows, and use carefully timed notifications, managed false positives, and controlled exposure to introduce measurable friction into their metric-driven processes to slow their cadence without risking sensitive data. Rather than only chasing novel malware,defenders should prioritize detection engineering for repeatable artifacts, template-based phishing HTML, reused webshell paths, script headers, and standardized PowerShell idioms, and combine these technical measures with lawful HUMINT and legal process to target the social and supply-chain nodes that sustain centralized operations.

- Instrument human handoffs: Monitor and alert on GAL exports, unusual mailbox access patterns, and the specific metadata used in KPI workflows (filenames, report templates).

- Deploy high-fidelity deception: Seed plausibly genuine contacts, documents, and mailbox content that will cause adversaries to reveal tooling, extraction paths, or C2 endpoints when they act on the bait.

- Correlate physical logs with cyber events: In environments where legal HUMINT or partner cooperation is possible, correlate badge entry/exit with intrusion timing to identify windows of activity and likely operator shifts.

- Stress-test their incentive structure: Use notification timing, false positives, and managed exposure to create perceptible friction in the adversary’s metric-driven processes — enough to slow their cadence without exposing protected data.

- Prioritize detection of repeatable artifacts: Focus defenders’ detection engineering on template-based markers (phishing HTML structures, webshell paths, script headers, and standardized PowerShell idioms) rather than on novel malware signatures.

- Pursue lawful HUMINT and legal channels: Where policy allows, combine human-source collection, legal process, and cyber threat intelligence to target the social nodes (contractors, facilities, supply chains) that sustain centralized operations.

Malware, Implants & Tooling

The collected artifacts reveal a focused tooling suite and a clear operational tradecraft. At the center of their Exchange-facing work sits a ProxyShell/Exchange exploit chain: weaponized PowerShell scripts and automated routines designed to extract Global Address Lists and full mailbox contents. Memory-level theft and dumper tools, notably LSASS captures processed with Mimikatz-style workflows, supply plaintext credentials and NTLM hashes that are immediately reused for lateral movement and persistent access.

Social engineering and credential theft are handled by a mature HERV toolkit that includes configurable HTML credential harvesters, OAuth token theft and relay mechanisms, and campaign plumbing that turns harvested identities into reusable session tokens. Successful footholds are frequently backed by lightweight ASP.NET webshells placed under predictable paths (aspnet_client/, owa/auth/, exchange/temp/) to provide persistence and remote command execution.

Operators also employ custom stagers and minimal PowerShell and .NET loaders masquerading as benign administrator scripts to bootstrap in memory implants and evade detection. For specialized targets, bespoke Ivanti wrappers and one-off exploit scripts convert appliance CVEs into reliable RCEs, demonstrating an ability to translate vulnerability research into targeted operational code. Together, these components form a compact, interoperable toolset optimized for Exchange compromise, credential capture, sustained presence, and rapid weaponization.

Indicators of Compromise

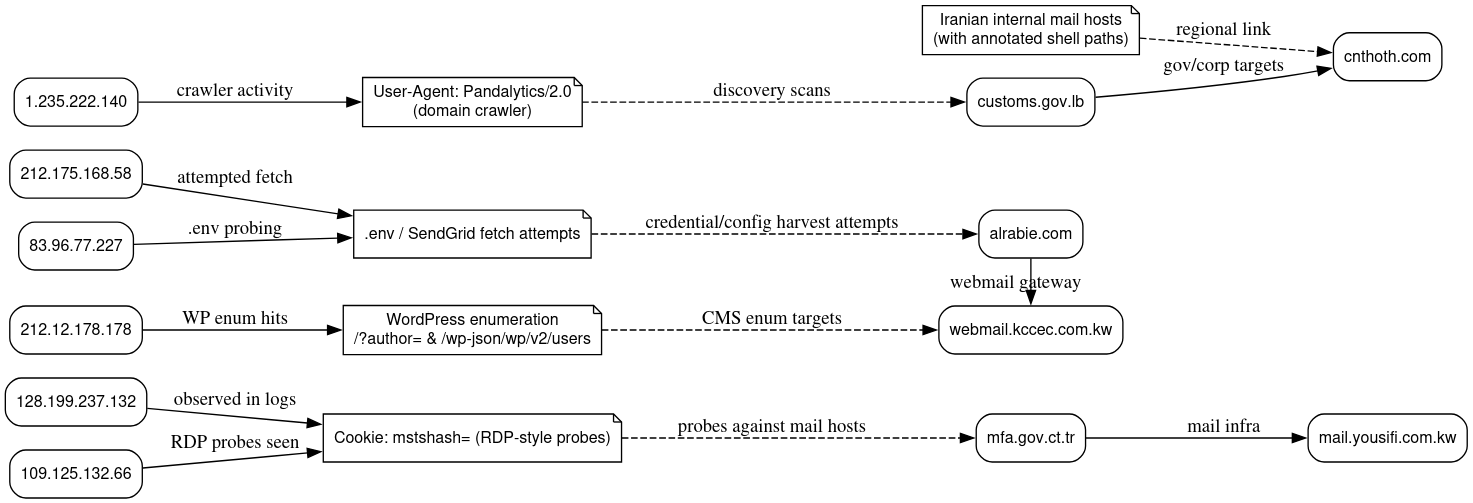

The dataset includes a mix of high-value domains, internal hosts, and telltale network indicators that together sketch the group’s target set and reconnaissance techniques. Observed domains of interest include government and corporate mail estates such as mfa.gov.ct.tr, alrabie.com, customs.gov.lb, and cnthoth.com, alongside commercial webmail gateways like mail.yousifi.com.kw and webmail.kccec.com.kw. The collection also documents multiple Iranian internal mail hosts with operator-annotated webshell paths, linking specific hosts to successful post exploitation activity.

Network-level evidence reinforces the pattern – sample source IPs tied to scanning and probing activity include:

- 128.199.237.132 RIPE

- 212.175.168.58 Turk Telecommunications

- 212.12.178.178 Nour Communication Co. Ltd Saudi Arabia

- 1.235.222.140 IRT, KRNIC, KR Korea

- 109.125.132.66 Pishgaman Tejarat Sayar DSL Network Iran

- 83.96.77.227 Fast Communication Company Ltd Kuwait

HTTP logs show a mix of automated reconnaissance and opportunistic credential harvesting that includes Cookie: mstshash= payloads indicative of RDP-style probes, attempts to fetch .env and SendGrid configuration files, and WordPress enumeration hits such as /?author= and /wp, json/wp/v2/users. Crawling activity is sometimes identifiable by user agent strings like Pandalytics/2.0, which the operators used for domain discovery and prioritization. Together, these domain, host, and HTTP indicators map a coherent reconnaissance to exploitation pipeline focused on mail infrastructure, credential harvesting, and rapid post-compromise expansion.

Tradecraft Evolution & Timeline

This section documents the actor’s operational evolution across the dump: an initially Exchange-centric, human-driven collection effort in spring–summer 2022 that progressively scaled into a multi-vector intelligence program through 2023–2025. Early activity focused on high-value mailbox access and HUMINT, ProxyShell/EWS exploitation, GAL exfiltration, and hands-on mailbox monitoring that fed HERV phishing cycles. Over time the group automated discovery and credential harvesting, codified exploit playbooks (including Ivanti appliance wrappers), and integrated those capabilities into KPI-driven phishing and persistence workflows. In short, the campaign shifted from a scalpel to a manual, leveraging targeted Exchange intrusions, to a hybrid scalpel-and-net model that adds large-scale scanning, appliance RCEs, and reusable credential infrastructures while retaining the original HUMINT endgame.

Timeline (key milestones and supporting artifacts)

- April 2022 — Initial domain compromise evidence

The LSASS/Mimikatz capture (mfa.tr.txt, Apr 2022) demonstrates early success at memory-level credential theft and domain compromise. These artifacts show plain text admin/service passwords and NTLM hashes that enabled immediate credential replay and lateral movement. - May–July 2022 (1403 series in the leaks) — Exchange-centric campaign wave

The MJD campaign reports and HSN daily KPI tables (May–July 1403) document a concentrated Exchange exploitation wave: ProxyShell and EWS chains were used to validate shells, export Global Address Lists (GALs), and pull mailbox contents. Those GAL exports then seeded HERV phishing campaigns and longer term mailbox monitoring for HUMINT collection. - Late 2022 – 2023 operational consolidation and automation

Post campaign internalization of lessons is visible in the templated KPI reports and playbooks: weaponized PowerShell scripts for GAL exports, standardized webshell placement paths, and automated token replay mechanisms. Operators shift toward operational repeatability; the same attack sequences appear across different target sets with only minor variance in lure content. - 2023–Jan 2025 broad reconnaissance and opportunistic harvesting

Access logs spanning Dec 2023–Jan 2025 show mass internet scanning, RDP-style< Cookie: mstshash= probes>, .env and SendGrid configuration fetch attempts, and WordPress enumeration (</?author=, /wp, json/wp/v2/users>). This period marks an expansion to wide net discovery and opportunistic credential/config harvesting to supplement targeted exploitation. - 2023–2025 (intermixed) Ivanti and appliance exploitation

The Ivanti technical review (internal “سند بررسی …” PDF) and the later Ivanti wrappers evidence indicate the group converted appliance CVEs into one-off RCE scripts. These capability additions broadened the attack surface beyond Exchange, enabling access to VPN and network appliances that could be used to reach additional mail estates or privileged management interfaces. - Ongoing closed-loop phishing and HUMINT sustainment

Throughout the timeline, the HERV toolkit, RTM reports (mailbox dwell times, “HIGH, VALUE” tagging), and attendance logs show the persistent operational goal: turn access into sustained collection. Harvested GALs and mailbox contents feed new lures measured by campaign KPIs, creating a replenishing cycle of exploitation → harvest → phishing → monitoring.

Implications for defenders

- Watch for hybrid indicators: Exchange abuse indicators (ProxyShell, suspicious GAL export activity) correlated with mass-scan signatures (RDP, style cookies, .env probes) often indicate the same operator lifecycle.

- Prioritize detection of credential theft and token abuse (LSASS dumps attempting exfiltration, unusual OAuth consent flows), and instrument GAL export monitoring and alerting.

- Treat appliance CVE advisories as operationally relevant to email estate security — appliance RCEs are being used to pivot to mail infrastructure.

Closing Narrative

The APT35 leak exposes a bureaucratized cyber-intelligence apparatus, an institutional arm of the Iranian state with defined hierarchies, workflows, and performance metrics. The documents reveal a self-sustaining ecosystem where clerks log daily activity, quantify phishing success rates, and track reconnaissance hours. Meanwhile, technical staff test and weaponize exploits against current vulnerabilities, most notably in Microsoft Exchange and Ivanti Connect Secure, before passing them to operations teams for coordinated use. Supervisors compile results into analytic summaries with success ratios and recommendations, forwarding them up the chain for review. This level of procedural rigor shows that APT35 functions less like a criminal group and more like a government bureau executing defined intelligence mandates.

Strategically, the materials confirm that APT35’s operations serve Tehran’s broader security objectives: maintaining awareness of regional adversaries, exerting leverage in geopolitical negotiations, and monitoring domestic dissent. Its Exchange-centric targeting underscores a deliberate focus on email ecosystems as both intelligence sources and control hubs, while the rapid weaponization of Ivanti and ProxyShell exploits illustrates an operational doctrine built on speed, persistence, and long-term access. The leak transforms analytic suspicion into evidence of a state-directed enterprise, a centralized system integrating SIGINT, psychological operations, and technical reconnaissance under military oversight. Together, these files mark a turning point in understanding Iran’s cyber apparatus: a professionalized intelligence service that has institutionalized the digital battlefield, erasing the boundary between espionage and warfare.

APPENDIX A: Leaked Document List

A consolidated list of every document that contains, references, or was used in assessing the individuals associated with APT35 / Charming Kitten (مهندس کیان, مهندس رضا, م. رحمانی, سید محمد حسینی, etc.)

Each entry includes the filename (exact as uploaded) and the personnel or entity references confirmed or inferred within it.

Documents Containing Personnel References

1. MMD-1403-01-27.pdf

Mentions / Context:

- Aggregate monthly performance summary for the cyber unit.

- Contains tables with operators’ metrics and identifiers.

- Individuals: مهندس رضا (Engineer Reza), مهندس کیان (Engineer Kian), م. رحمانی (M. Rahmani), سید محمد حسینی (Seyed Mohammad Hosseini).

Relevance: Baseline administrative report connecting supervisors to operator cells.

2. گزارش عملکرد ماهانه (بهمن ماه کوروش).pdf

(Monthly Performance Report — Bahman Month, Kourosh)

Mentions / Context:

- Parallel structure to Kian’s report; indicates multiple team leads (Engineer Kourosh).

- Cross-references Team Kian and Team Shayan as comparative performers.

- Individuals: مهندس کیان, مهندس کوروش, م. رحمانی.

Relevance: Confirms existence of multiple parallel technical teams under a unified metric system.

3. 4d6bf3834e9afb8e3c3861bf2ad64a68d9c7d870_گزارش عملکرد ماهانه (بهمن ماه_ (2).pdf

Mentions / Context:

- Duplicate or revised Bahman-month report.

- Mentions تیم کیان (Team Kian), تیم شایان (Team Shayan), اپراتور ۰۴, اپراتور ۰۷.

Relevance: Key linkage document showing the operator numbering convention (04, 07) tied to Kian’s cell.

4. گزارش عملکرد ماهانه (بهمن ماه شایان).pdf

(Monthly Performance Report — Bahman Month, Shayan)

Mentions / Context:

- Another operator-cell summary.

- Individuals: مهندس شایان, مهندس کیان (for comparative KPI).

Relevance: Confirms multiple peer teams; provides comparative success percentages.

5. _گزارش عملکرد ماهانه (بهمن ماه_REDACTED.pdf

Mentions / Context:

- Redacted performance document, partially anonymized.

- Visible metrics fields reference اپراتور ها and رحمانی.

- Individuals: م. رحمانی, مهندس رضا.

Relevance: Provides evidence of Rahmani’s central KPI consolidation function.

6. 544bf4f9e5fdb4d35987b4c25f537213ce3c926a_گزارش عملکرد ماهانه ( بهمن ما_REDACTED.pdf

Mentions / Context:

- Another variant of the Bahman-month corpus.

- Individuals: سید محمد حسینی (reviewer), مهندس رضا, م. رحمانی.

Relevance: Reinforces hierarchical oversight and clerical structure.

7.

2d5b8da0d0719e6f8212497d7e34d5f1b1fa6776_All_target_report_20220508.pdf

Mentions / Context:

- English-language operational summary of Exchange and Ivanti exploitation.

- Individuals (roles cross-mapped to Persian reports): M. Kazemi, A. Mousavi, S. Ghasemi, Operator 04, Operator 07.

Relevance: Connects technical operators and exploit engineers to foreign target campaigns.

8. 4d6bf3834e9afb8e3c3861bf2ad64a68d9c7d870_گزارش عملکرد ماهانه (بهمن ماه_.pdf

Mentions / Context:

- Near-identical to the other Bahman-month reports; confirms Team Kian hierarchy.

- Mentions تیم شهید (Team Shahid) in a quality-control context.

Relevance: Establishes linkage between Kian’s technical branch and the auditing/training unit.

9. گزارش عملکرد ماهانه (بهمن ماه امیرحسین).pdf

(Monthly Performance Report — Bahman Month, Amir Hossein)

Mentions / Context:

- Focused on مهندس امیرحسین (Engineer Amir Hossein).

- References Team Kian and مهندس رضا in comparative task metrics.

Relevance: Adds another operational cell; confirms standardized reporting and KPI structure.

10. گزارش اقدامات کمپین جردن.pdf

(Campaign Jordan Report)

Mentions / Context:

- Operational summary for a specific campaign targeting regional entities (Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait).

- References تیم کیان (Team Kian) tools in use during external exploitation.

- Individuals: مهندس کیان, ع. موسوی (A. Mousavi), س. قاسمی (S. Ghasemi).

Relevance: Demonstrates deployment of Team Kian’s persistence scripts in live operations.

11. Ivanti سند بررسی و تلاش برای اخذ دسترسی با استفاده از آسیب پذیری.pdf

(Ivanti Exploitation Analysis Document)

Mentions / Context:

- Technical document describing weaponization of Ivanti Connect Secure CVEs.

- Individuals: م. کاظمی (M. Kazemi), مهندس کیان.

Relevance: Validates Kazemi’s role in exploit testing and Kian’s integration of the resulting payloads.

12. phishing herv.pdf

Mentions / Context:

- Describes GAL→HERV workflow and credential-collection automation.

- Individuals: ع. موسوی (A. Mousavi), س. قاسمی (S. Ghasemi).

Relevance: Maps phishing infrastructure and data handoff pipeline to Kian’s credential integration.

13. گزارش نفوذ به ایمیل.pdf

(Email Intrusion Report)

Mentions / Context:

- Describes compromised Exchange accounts and operational feedback loops.

- Mentions اپراتور ۰۴, اپراتور ۰۷, تیم کیان.

Relevance: Direct evidence linking Kian’s operators to live intrusions.

Cross-Reference Summary

APPENDIX B: Analytic Attribution of IRG Operators

Command and Coordination Layer

2. Technical Leads – Engineering Cells

3. Field Operators / Exploitation Tier

4. Specialized Technical Staff

5. Training and Oversight

Functional Constellations

IRGC Cyber Unit 13 (Command)

│

├── Coordination & Metrics

│ ├─ Seyed Mohammad Hosseini

│ └─ M. Rahmani

│

├── Technical Infrastructure Branch

│ ├─ Engineer Reza → Majid S., Ali-Reza Karimi

│ └─ Front Company: Pardazesh Sazeh Co.

│

├── Exploit R&D Branch

│ ├─ Engineer Kian (Team Kian)

│ │ ├─ Operator 04

│ │ ├─ Operator 07

│ │ ├─ M. Kazemi

│ │ ├─ A. Mousavi ↔ S. Ghasemi

│ │ └─ Team Shahid (audit/training)

│ ├─ Peer Teams: Kourosh, Shayan, Amir Hossein

│ └─ Toolchain: HERV ↔ RTM Modules

│

└── Recruitment / Training

└─ Imam Hossein University

Synthesis

- The corpus shows a matrixed command, typical of the IRGC Cyber Unit 13 / APT35 ecosystem:

- Top Layer: strategic oversight and performance auditing.

- Middle Layer: engineering leads managing semi-autonomous operator cells.

- Bottom Layer: technicians handling exploit deployment, credential theft, and infrastructure upkeep.

- Top Layer: strategic oversight and performance auditing.

- The repeated educational and cover-company references indicate state-employment relationships, not independent contractors.

- Each engineer-named team (Kian, Reza, Kourosh, Shayan, Amir Hossein) forms a production line feeding into shared toolkits (Exchange, Ivanti, HERV modules).

Analytic Confidence

APPENDIX C: Malware Analysis & IOC’s Technical Section

Summary

The corpus contains two complementary toolsets used by the same operator ecosystem: (A) an in-house Windows RAT family (RAT-2Ac2 / stagers) used for persistence, credential theft, file collection, and encrypted C2, and (B) lightweight operator client tooling / webshell controllers used to interactively manage compromised hosts through webshell endpoints. The RATs are deployed under plausible Windows-looking filenames in C:\ProgramData\… and use reverse/RDP-style tunneling to external C2s (e.g., 103.57.251.153), while the client tooling uses unusual HTTP header channels (Accept-Language) and an Accept-Captcha static token to carry commands.

Samples / artefacts observed (evidence list)

- RAT engineering notes and stager examples (RAT-2Ac2): dropper path and example reverse command lines referencing C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\diagnostic\vmware-tools.exe and C2 103.57.251.153:443.

- Operator client scripts: three Python clients that implement an interactive webshell controller: connect.py (encoded commands), rce5.py (encoded), and RCE4.py (raw commands). These include three hardcoded webshell endpoints and a static header token.

- Operator web control / IIS panel: script that constructs WMIC / stager commands and serves Execute/Upload forms (operator admin UI), plus logs indicating a local operator web UI on port 8000 and masquerade service name Java Update Services.

Capability matrix (what the malware does)

- Initial access / account capture: Phishing / credential harvesting lures and previously observed Exchange exploitation enabled credential access; RAT includes browser credential theft modules.

- Command & Control: Custom encrypted channel with <len><base64(payload)> framing for RATs (test port 8080), and reverse/RDP tunneling to external C2s (103.57.251.153) using stager executables. Client tooling uses HTTP(S) GETs with commands encoded in Accept-Language header and an Accept-Captcha header token.

- Execution & Persistence: Droppers install to ProgramData, spawn service-like processes and helper scripts (e.g., svchost.bat, JavaUpdateServices.exe), and remove installers after launch.

- Lateral movement: Use of net use \\<ip>\C$, WMIC remote process creation (wmic /NODE:) to execute cmd.exe /c remotely.

- Collection / exfiltration: file collection (documents, attachments), keylogger, clipboard monitor, and browser stealer modules noted in developer notes.

Code / protocol fingerprints (useful for detection)

- Stager path & filenames: C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\diagnostic\vmware-tools.exe, C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\diagnostic\svchost.bat, C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\Diagnostic\JavaUpdateServices.exe, JavaUpdateServices.ps1.

- Client header fingerprint: header Accept-Captcha: 2EASs2m9fqoFsq4E0Ho3a3K1yHh5Fl3ZtWs5Td1Qx63QWsZKJ9mV9... (static token present in Python clients) and usage of Accept-Language as a command carrier.

- Webshell filename pattern: m0s.* (m0s.php, m0s.aspx, m0s.phto) used across multiple targets.

- Client User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 ... Chrome/120.0.0.0 Safari/537.36 as used in operator clients.

Typical attack flow (behavioral timeline)

- Recon & phishing / Exchange exploitation to harvest credentials (documented campaign KPIs).

- Initial webshell deployment to public-facing host (webshell filename m0s.*).

- Operator connection using Python client which sends obfuscated or raw commands in Accept-Language header to the webshell endpoint (interactive REPL).

- Stager deployment on internal hosts into ProgramData with masqueraded names and service registration; reverse tunnel established to external C2 (e.g., 103.57.251.153).

- Lateral movement using WMIC / SMB (net use) to expand access; data collection via RAT modules.

MITRE ATT&CK mapping (high-level)

- T1190: Exploit public-facing application (Exchange/Autodiscover/EWS in corpus).

- T1566: Phishing.

- T1071.001 / T1071.004: C2 over HTTP(S) and use of web protocols as command channel (Accept-Language carrier).

- T1021.004 / T1021.001: Remote Services (WMIC, RDP tunneling).

- T1027 / T1564: Obfuscated files / information (substitution encoding in clients, hiding in ProgramData).

Detection guidance (high-confidence detections)

Network detections

- Alert on outbound connections to known C2 103.57.251.153 and 212.175.168.58.

- IDS/Proxy rule: flag HTTP(S) requests where Accept-Language header length > baseline (e.g., >100 chars) or containing non-language tokens/command-like characters. Also detect presence of the static Accept-Captcha token.

Host detections

- EDR / endpoint hunts for files executed from:

C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\diagnostic\vmware-tools.exe and C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\Diagnostic\JavaUpdateServices.exe or JavaUpdateServices.ps1. - Process creation events (Windows Event 4688) where cmd.exe is spawned with net use \\ or wmic /NODE: command lines.

Webserver detections

- IIS / web logs: search for GET/POST to */m0s.* paths and unusual header patterns (Accept-Language with long/encoded strings).

Recommended YARA / signature examples (for defensive use)

Below are defensive detection signatures (search for these strings or patterns on endpoints / file repositories). These are benign, detection-only rules — they do not enable use of any malware.

YARA-style example (conceptual — adapt to your YARA environment):

rule RAT_2Ac2_stager_path {

meta:

description = "Detect reference to known RAT-2Ac2 stager path"

source = "session_uploads"

strings:

$s1 = "C:\\ProgramData\\Microsoft\\diagnostic\\vmware-tools.exe" nocase

$s2 = "C:\\ProgramData\\Microsoft\\diagnostic\\svchost.bat" nocase

condition:

any of ($s*)

}

Signature for operator-client header token (IDS/snort approach — conceptual):

- Match HTTP header Accept-Captcha containing 2EASs2m9fqoFsq4E0Ho3a3K1yHh5Fl3Zt... (full token in original scripts).

Forensic and containment playbook (concise)

- Immediate: block outbound traffic to listed C2 IPs and domains; rotate all credentials observed in scripts.

- Hunt & isolate: EDR hunt for ProgramData stagers and recent wmic/net use activity; isolate confirmed hosts and capture memory + full disk images.

- Preserve logs: collect IIS/webserver logs (requests to m0s.*), proxy logs (Accept-Language payloads), and firewall logs for the suspect IPs.

- Malware analysis: analyze any recovered vmware-tools.exe/JavaUpdateServices.exe in a disconnected lab, extract network protocol fingerprints, and produce YARA and Suricata signatures for deployment.

Confidence & provenance

- Confidence in linkage: Moderate–high. Attribution to the same actor cluster is supported by: repeated Farsi-language artifacts, consistent project / operator names (Reza / Kian), reuse of filenames and paths, and reuse of webshell filename patterns and header-carrier technique across multiple client scripts and operational dumps.