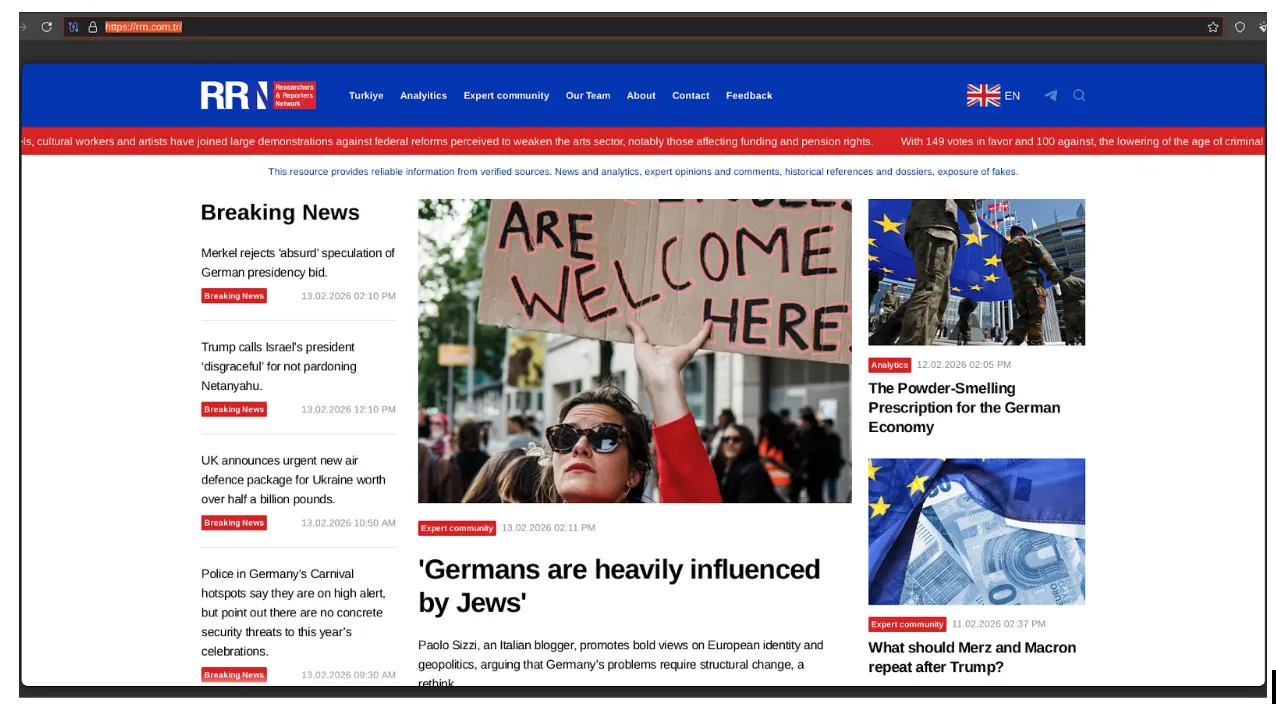

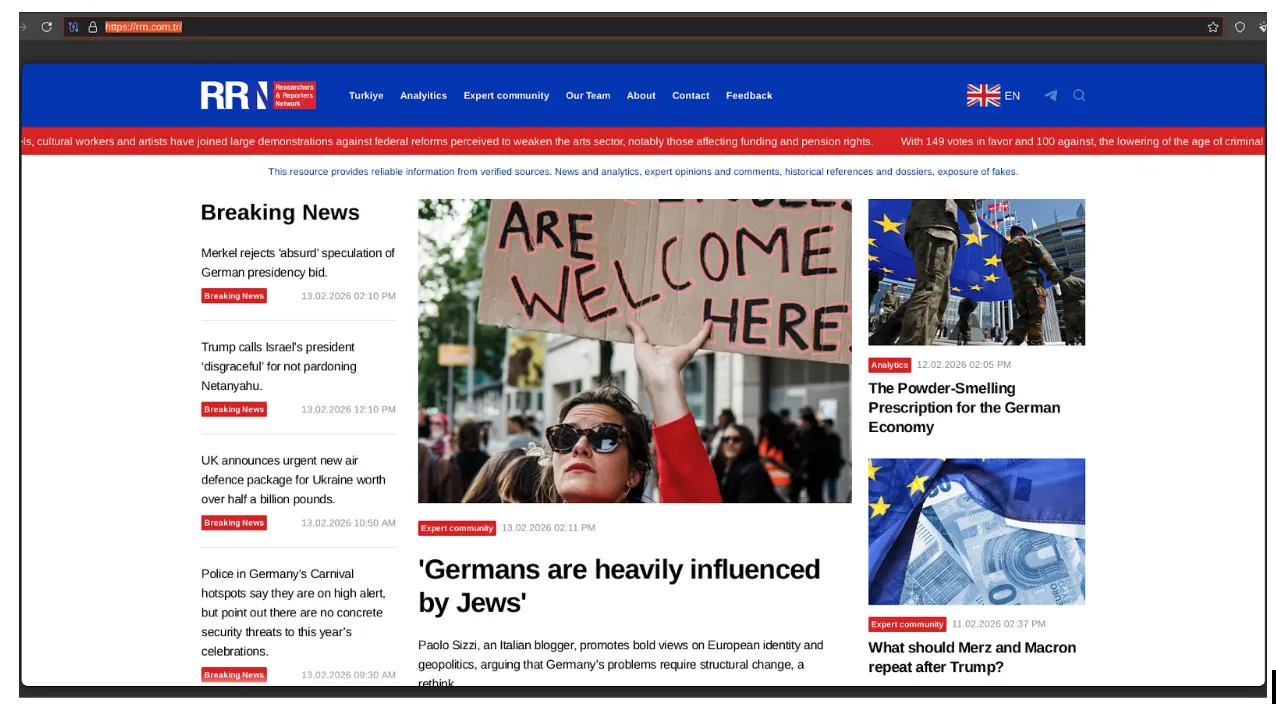

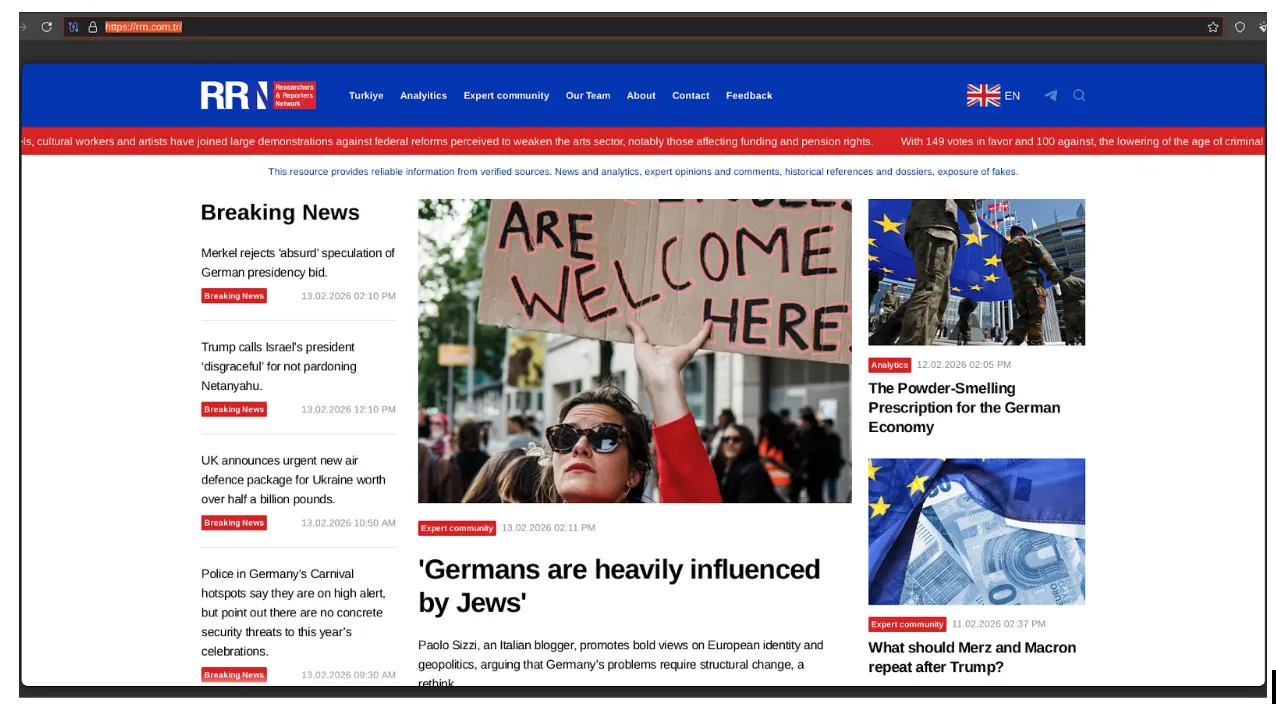

Analysis of the Doppelgänger / RRN disinformation ecosystem. Learn how this DevOps-style infrastructure uses automated media impersonation, TLD rotation, and cloud-native hosting to target global audiences and evade enforcement.

Analysis of the Doppelgänger / RRN disinformation ecosystem. Learn how this DevOps-style infrastructure uses automated media impersonation, TLD rotation, and cloud-native hosting to target global audiences and evade enforcement.

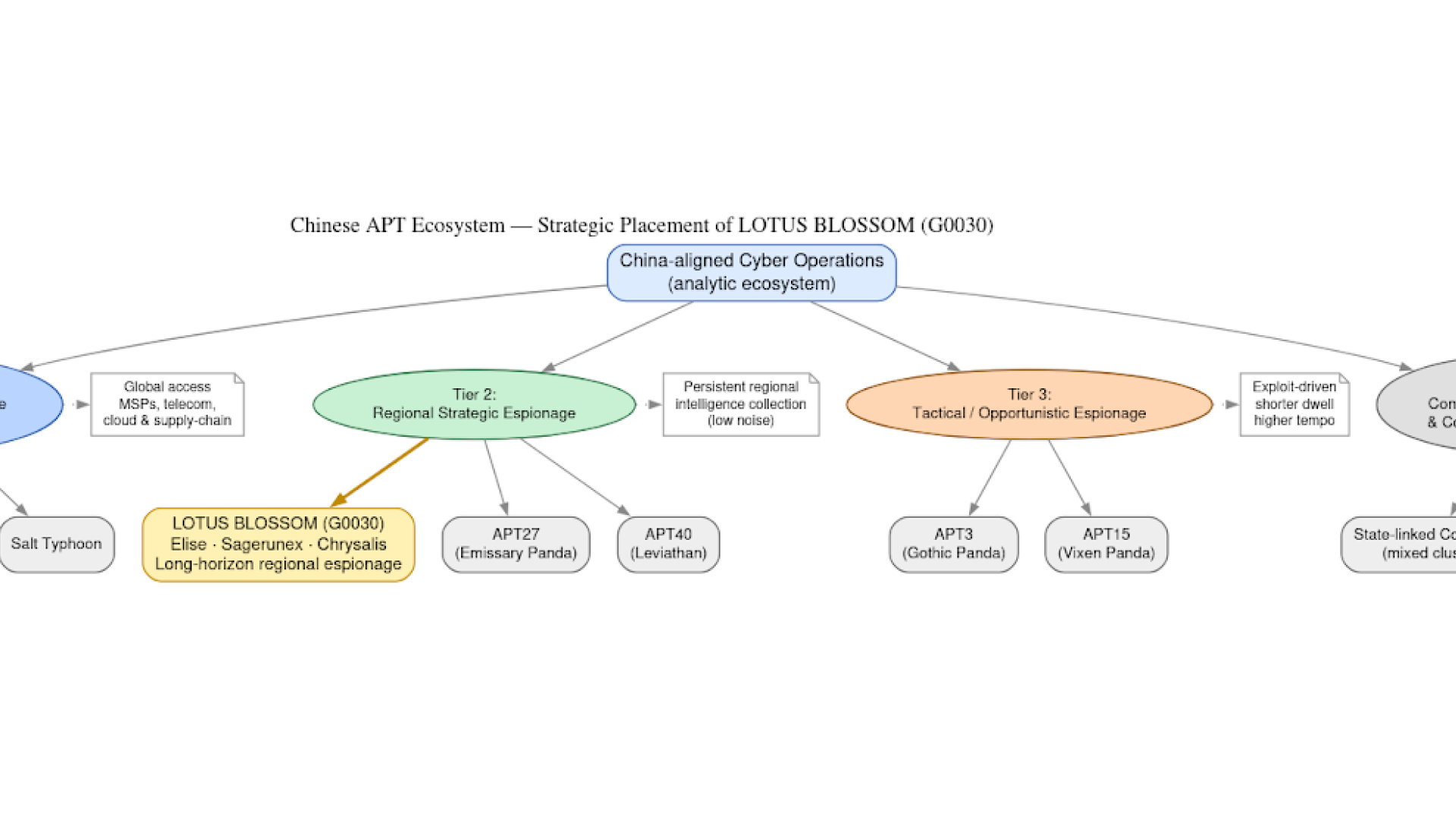

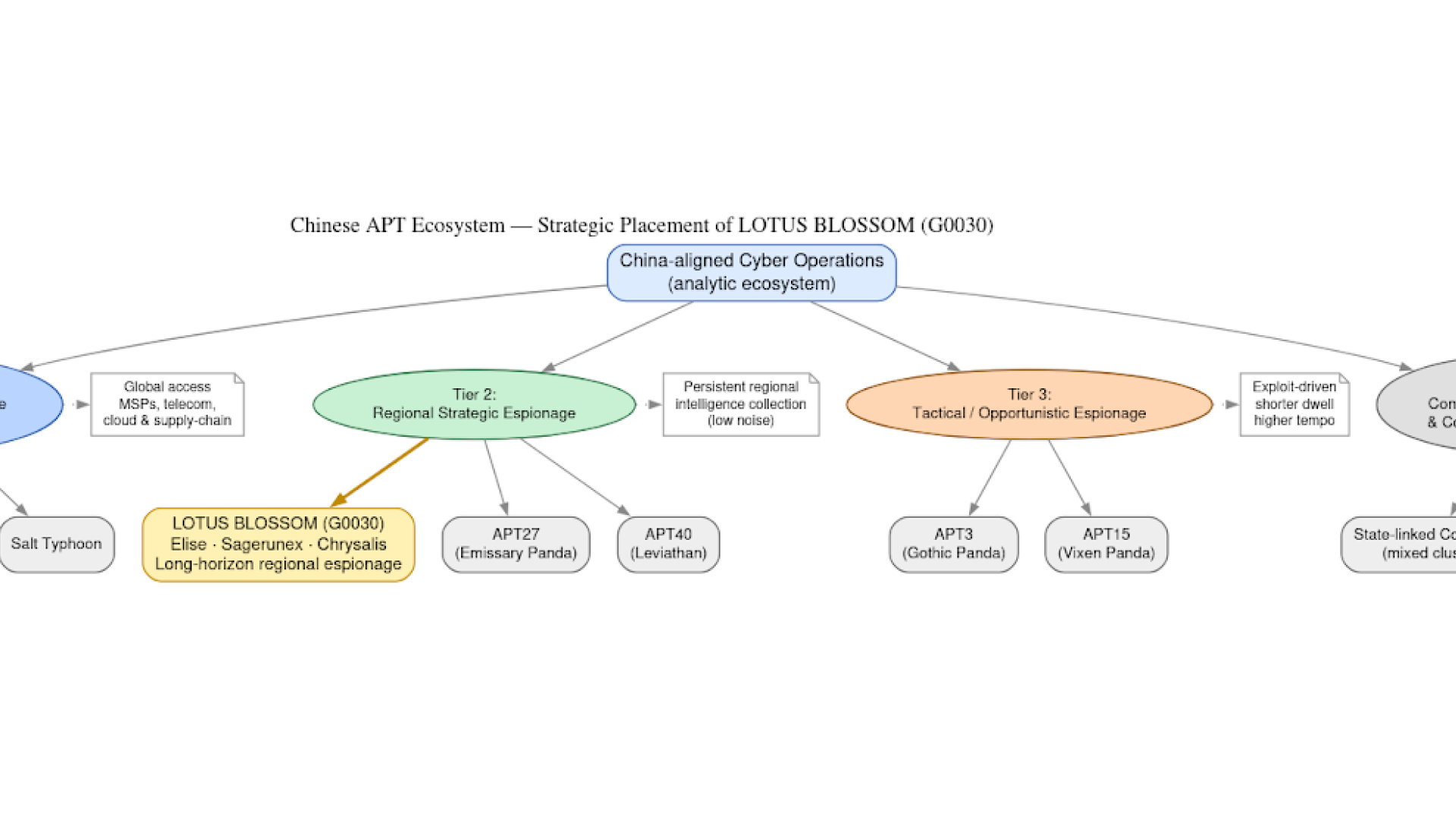

How Lotus Blossom (G0030) compromised the Notepad++ update pipeline in a precision supply-chain espionage campaign targeting high-value organizations.

Leaked Knownsec documents reveal China’s cyberespionage ecosystem. Analyze TargetDB, GhostX, and 404 Lab’s role in global reconnaissance and critical infrastructure targeting.

A broken snowblower belt taught me something cybersecurity professionals often forget — saying "I don't know" isn't failure. It's where the real work begins.

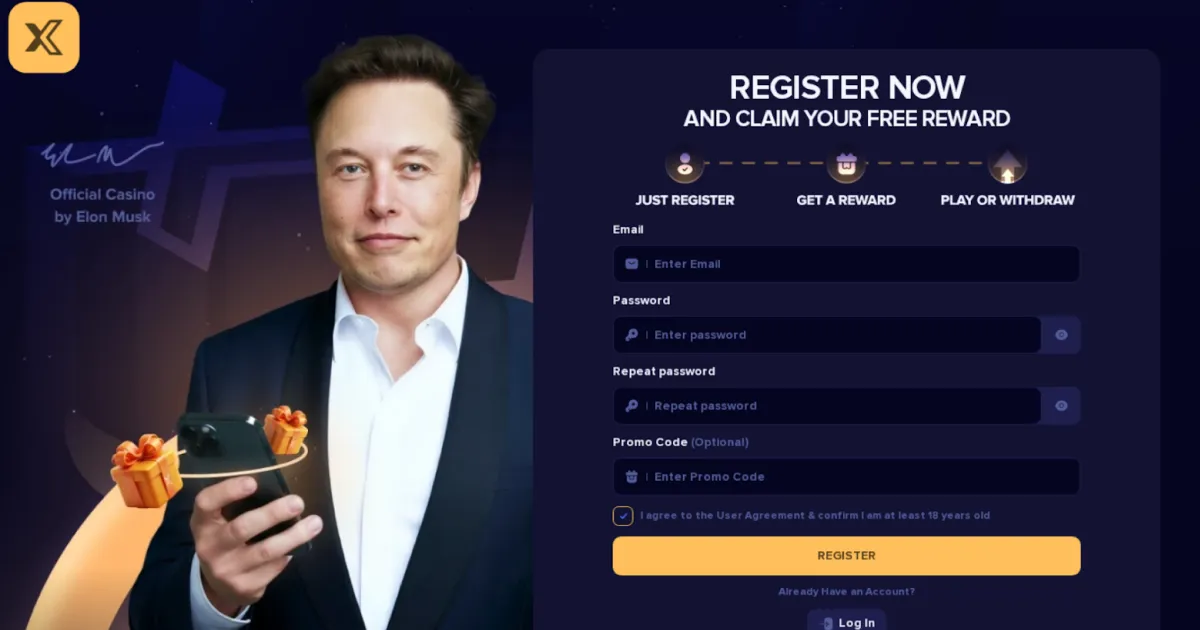

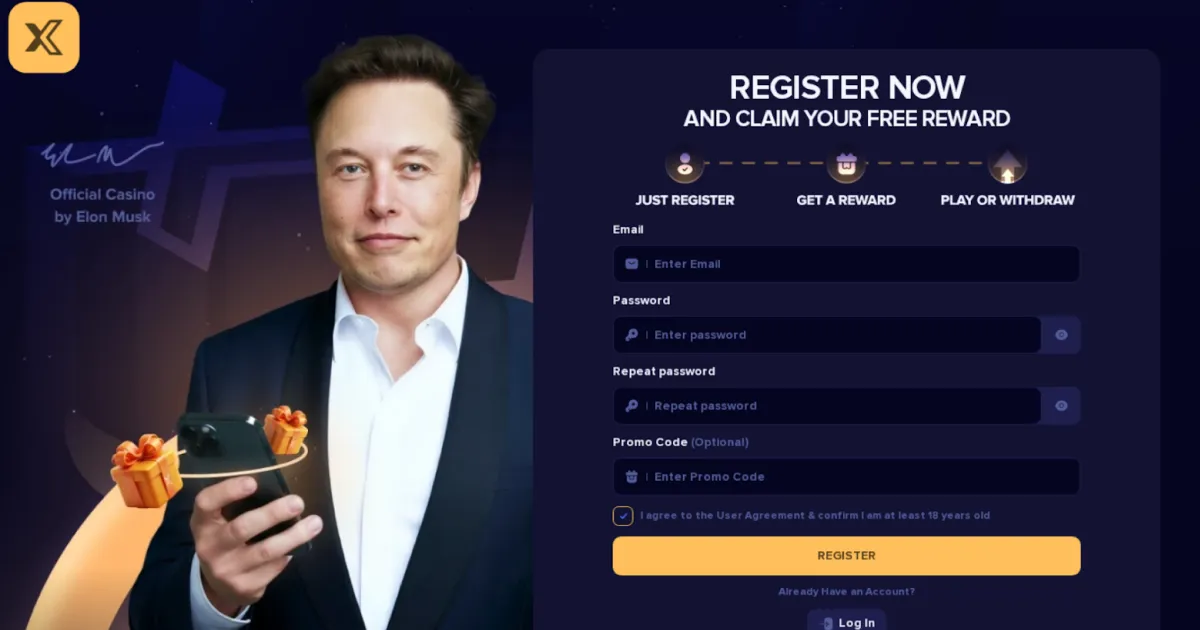

An analysis of an active cryptocurrency scam operation impersonating Trump, Musk, and Truth Social across 250+ domains — uncovering shared wallet infrastructure, on-chain laundering pipelines, and the tactics used to fake legitimacy.

Analysis of the Doppelgänger / RRN disinformation ecosystem. Learn how this DevOps-style infrastructure uses automated media impersonation, TLD rotation, and cloud-native hosting to target global audiences and evade enforcement.

How Lotus Blossom (G0030) compromised the Notepad++ update pipeline in a precision supply-chain espionage campaign targeting high-value organizations.

Leaked Knownsec documents reveal China’s cyberespionage ecosystem. Analyze TargetDB, GhostX, and 404 Lab’s role in global reconnaissance and critical infrastructure targeting.

A broken snowblower belt taught me something cybersecurity professionals often forget — saying "I don't know" isn't failure. It's where the real work begins.

An analysis of an active cryptocurrency scam operation impersonating Trump, Musk, and Truth Social across 250+ domains — uncovering shared wallet infrastructure, on-chain laundering pipelines, and the tactics used to fake legitimacy.

Commentary followed by links to cybersecurity articles and resources that caught our interest internally.