Inside the Great Firewall Part 3: Geopolitical and Societal Ramifications

The Great Firewall as Geopolitical Infrastructure

The Great Firewall of China (GFW) represents far more than a technical construct; it is the digital expression of a strategic doctrine, one rooted in state control, authoritarian stability, and a redefinition of sovereignty in cyberspace. Where earlier generations of internet architecture were built around openness and interoperability, the GFW stands as a counter-model: a system that enforces not just censorship but also discipline, not merely blocking information but engineering a compliant digital citizenry.

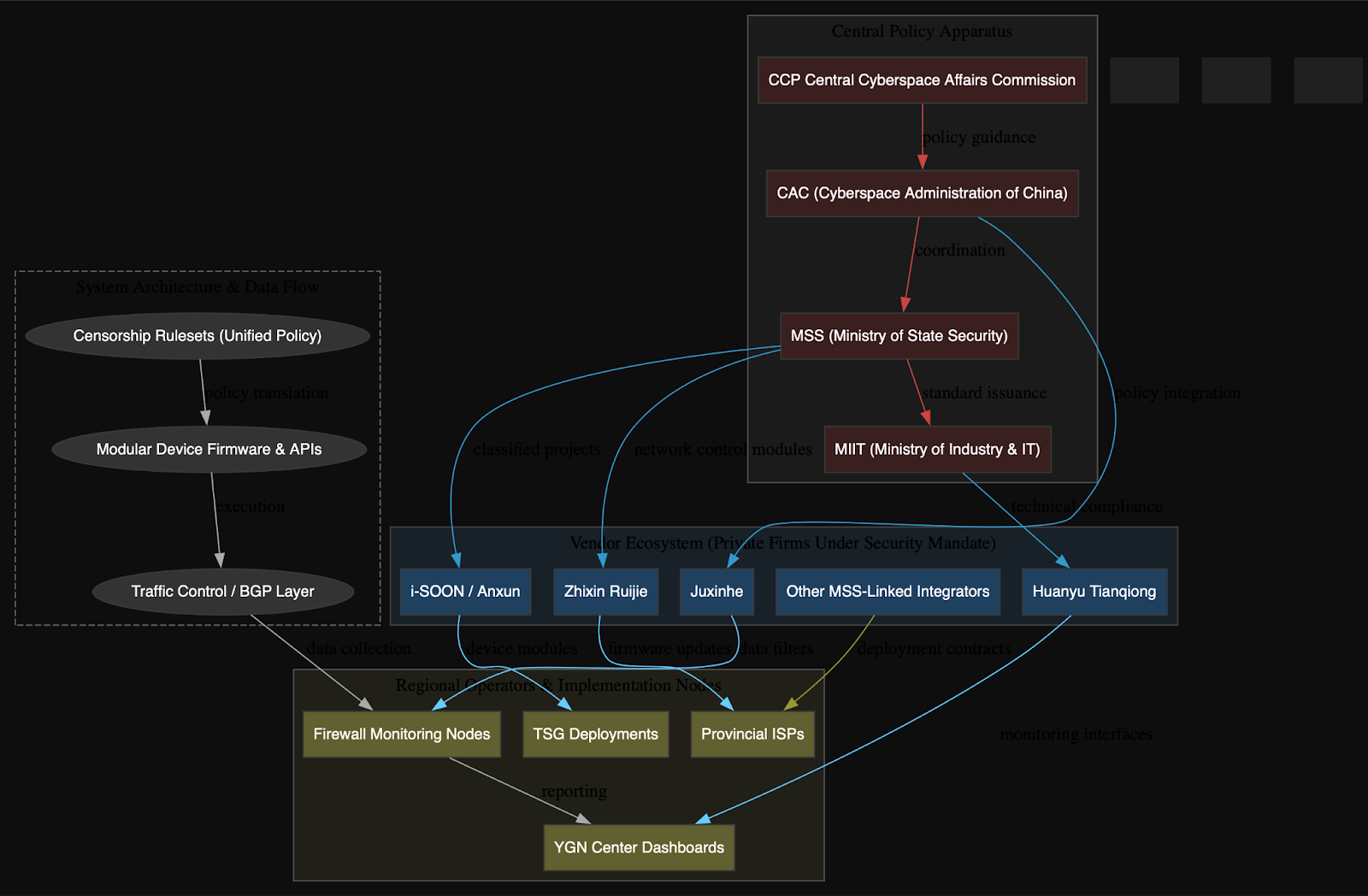

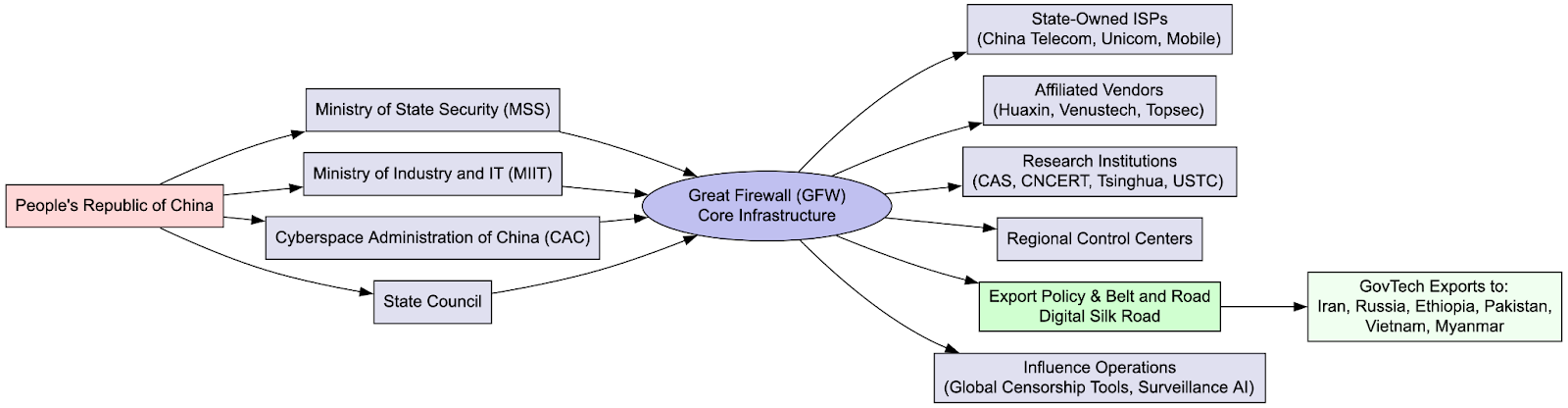

Through this lens, the GFW becomes a cornerstone of China’s broader governance model, extending internal social control mechanisms into the digital realm while also projecting power abroad. It is both shield and sword: insulating the domestic population from undesired narratives and foreign influence, while exporting technologies, protocols, and ideological models of digital sovereignty to other authoritarian or aspiring technocratic regimes. What began as a reactive security tool has evolved into a dynamic governance platform, tightly integrated with national infrastructure, industrial policy, propaganda channels, and law enforcement systems. Its architecture, as seen in the leaked data, supports real-time behavioral tracking, regionally adaptive enforcement, and centralized orchestration across ISPs, ministries, and military-linked vendors.

Internal Social Control: Domestic Implementation and Ideological Containment

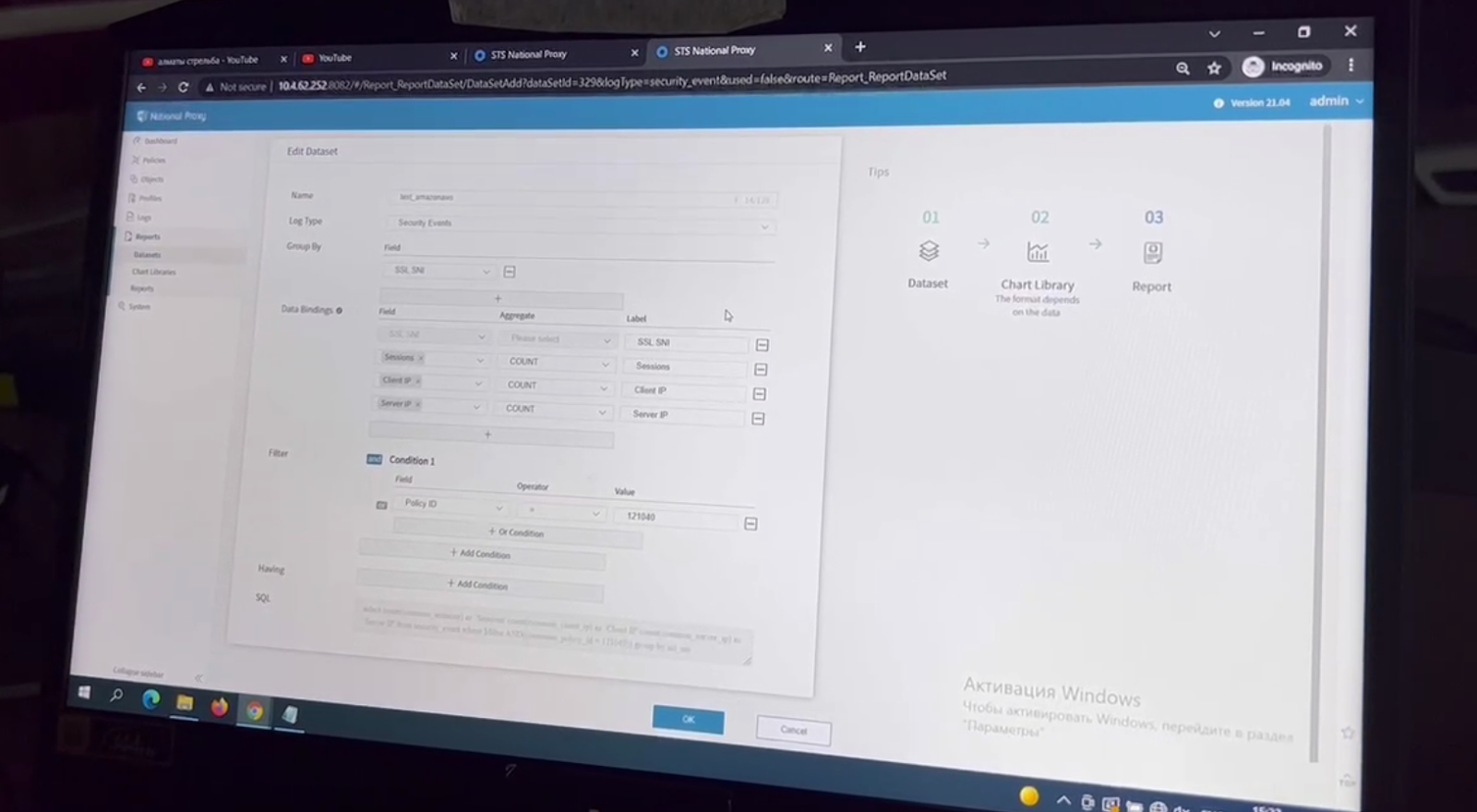

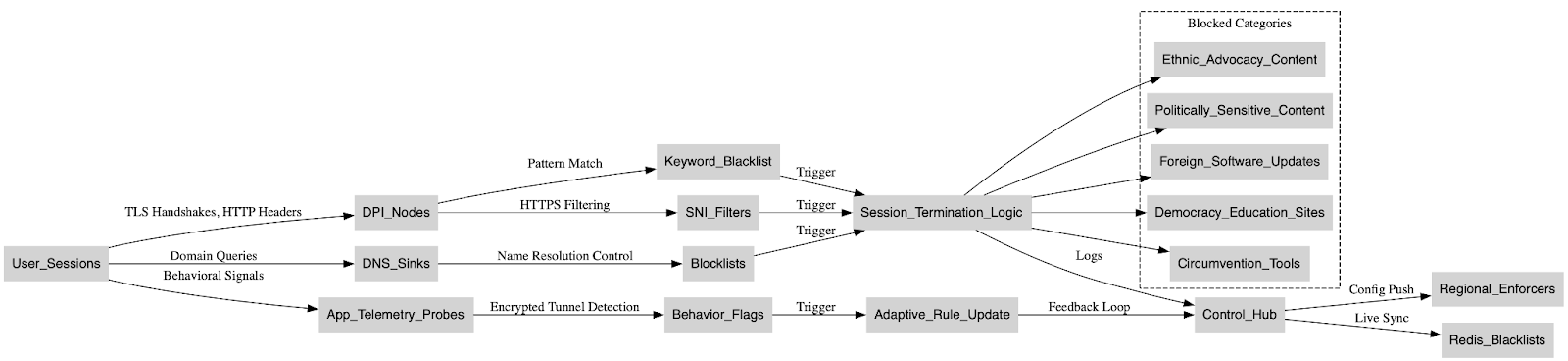

China’s domestic deployment of the Great Firewall (GFW) is not merely a digital barrier, it is an infrastructure for surveillance engineering that operates in service of ideological conformity and political control. The infrastructure revealed in the dataset showcases a system that is deeply embedded within the national internet architecture, capable of granular content classification, multi-layered traffic inspection, and adaptive suppression mechanisms. Every facet of user interaction, from HTTP headers and TLS handshakes to DNS queries and application telemetry, is a potential input for censorship decisions.

At its core, the GFW’s domestic function is ideological containment: a technical means to preempt the circulation of narratives, symbols, or software deemed threatening to Party legitimacy. The filtering mechanisms are not static, they exhibit dynamic heuristics that flag circumvention traffic patterns, encrypted tunnels, and access attempts to banned services such as Twitter, YouTube, Wikipedia, and GitHub. Logs and routing tables within the leaked data reveal strategic targeting of:

- Foreign software update servers, to prevent the installation of tools like Signal or Tor,

- Cloud services and content delivery networks (CDNs) associated with media organizations and dissident communities,

- Online education portals and democracy-linked content, particularly around anniversaries of events like Tiananmen Square,

- Religious and ethnic advocacy content, especially concerning Tibet, Xinjiang, and Falun Gong.

By mapping these access patterns to regions, user sessions, and endpoints, the GFW enables adaptive, real-time suppression, a form of algorithmic censorship that not only blocks, but surveils. The presence of regionally distributed “probe agents,” remote configuration push systems, and memory-optimized Redis-based blacklist updates shows a scalable enforcement model designed to track and shape the narrative landscape at population scale. This is not passive filtering; it is proactive thought boundary enforcement, engineered to neutralize dissent before it propagates.

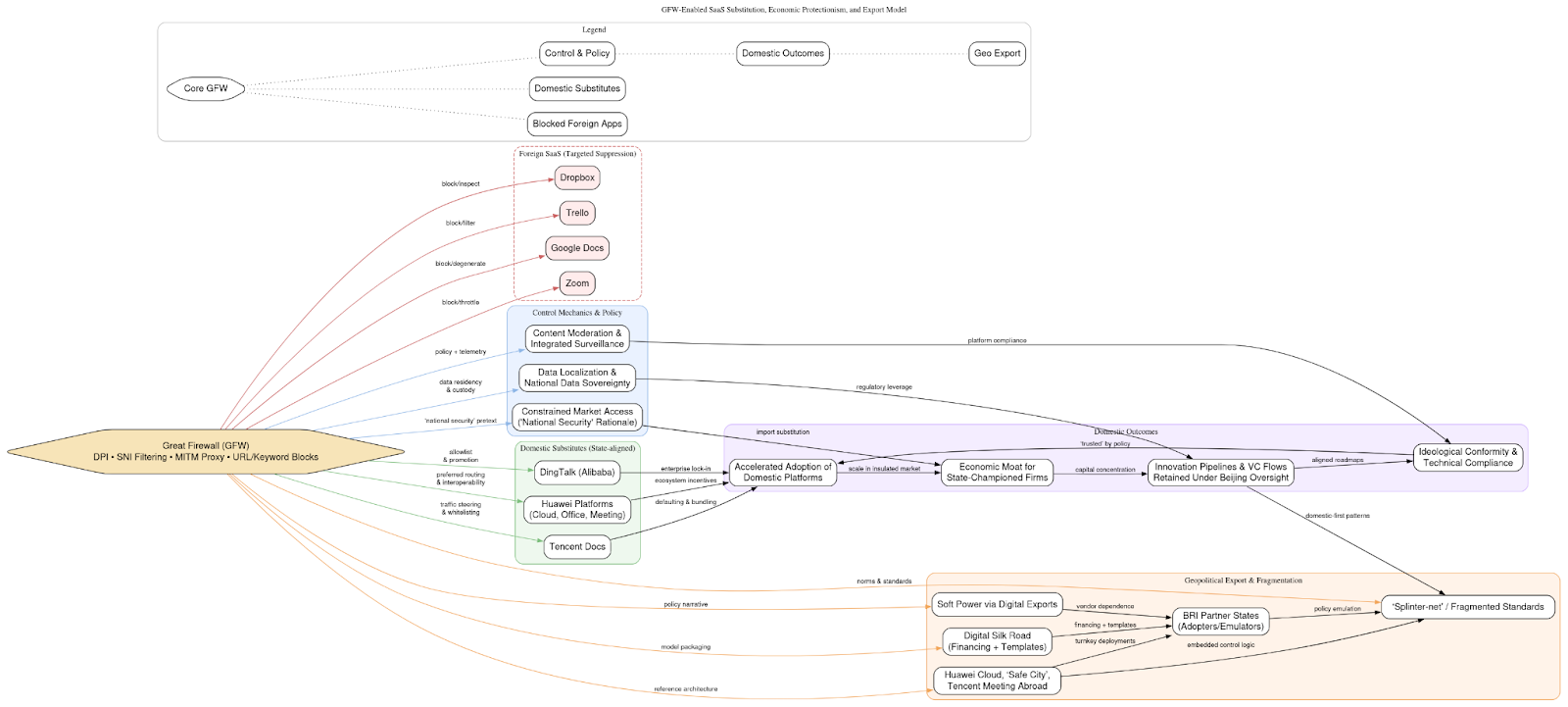

Economic Engineering and Domestic Substitution

By systematically blocking foreign SaaS and collaborative software, China nurtures its own domestic ecosystem. Excel-based audits from the dump show targeted suppression of applications such as Google Docs, Zoom, Dropbox, and Trello. These gaps are filled by Tencent Docs, DingTalk, and Huawei-developed platforms, illustrating how the GFW enables economic protectionism masquerading as cyber defense. This pattern is not incidental but strategic: the firewall constrains market access for foreign competitors under the guise of national security, while ensuring that data flows remain within the control of state-aligned corporations.

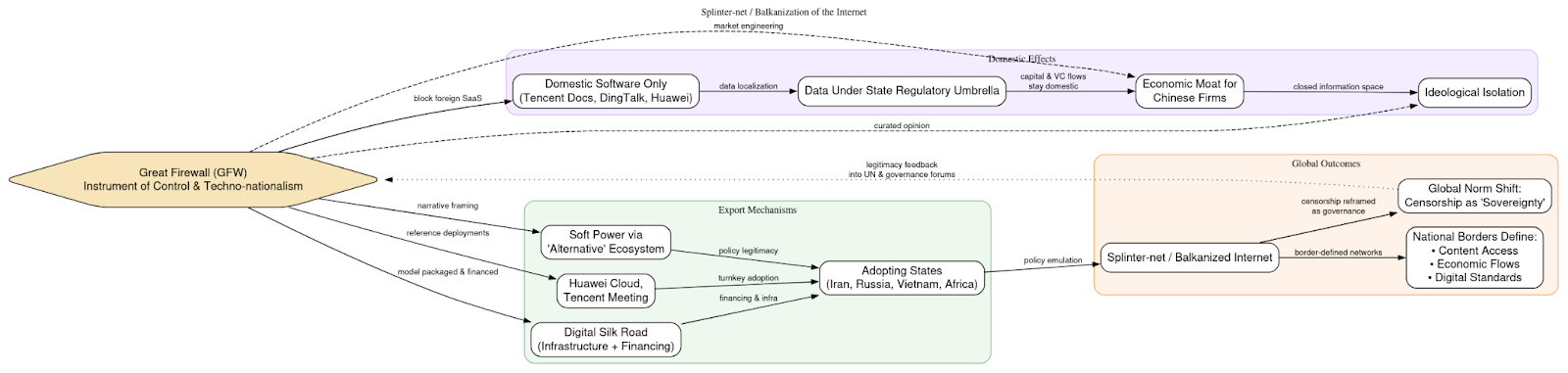

The substitution effect creates a dual outcome. First, it accelerates the adoption of domestic platforms that are deeply integrated with state surveillance and content moderation requirements, ensuring ideological conformity and technical compliance. Second, it generates an economic moat for Chinese firms by shielding them from the competitive pressures of global incumbents, allowing state-championed companies to scale rapidly in an artificially insulated market. What emerges is a model where censorship and market engineering are inseparable, cyber sovereignty and industrial policy reinforcing one another.

At a macro level, this reveals how the GFW is not only an instrument of political control but also a lever of techno-nationalism. By positioning domestic software as the only viable option for collaboration, communication, and file sharing, the state ensures that innovation pipelines, venture capital flows, and user data remain under Beijing’s regulatory umbrella. The firewall thus becomes a structural barrier to globalization, producing not only ideological isolation but also a controlled economic environment where China’s champions can thrive at the expense of suppressed foreign rivals.

On the geopolitical stage, this model contributes to the fragmentation of the global internet. As China’s approach is emulated by other authoritarian regimes, the result is a “splinter-net” or a “Balkanization of the internet”, where national borders dictate not just content but also economic flows and digital standards. Beijing leverages its ecosystem as a form of soft power, exporting platforms like Huawei Cloud and Tencent Meeting to Belt and Road partner states, presenting them as secure alternatives to Western software while embedding latent channels of influence and surveillance. In doing so, the GFW does not simply defend China’s information space, it actively reshapes global digital norms, setting precedents for a world where censorship and economic self-sufficiency converge as tools of statecraft.

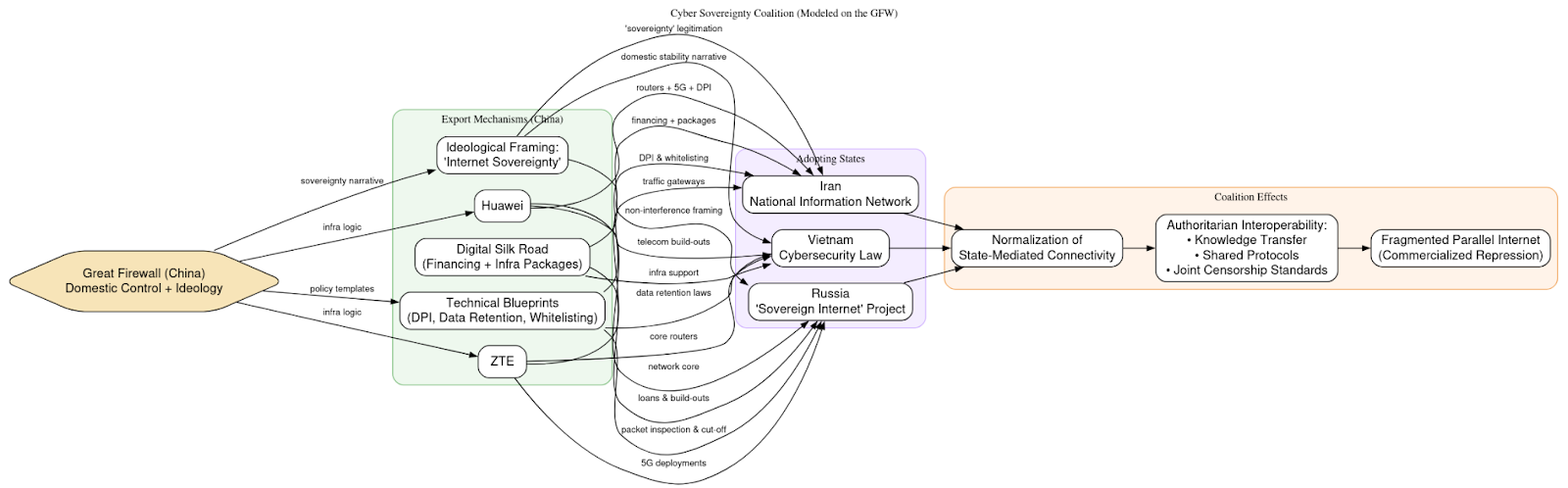

Regional Influence and the Export of Cyber Norms

As Beijing cements control internally, it also exports its digital governance model. Observed similarities in data retention mandates, DPI (Deep Packet Inspection) deployment, and application whitelisting mechanisms in countries such as Iran, Vietnam, and Russia suggest the emergence of a “cyber sovereignty coalition” modeled after the GFW. These states borrow not only the technical blueprints but also the ideological framing: the notion that national borders should extend into cyberspace, with governments controlling what citizens can access, publish, and share.

Chinese firms such as Huawei and ZTE play a central role in enabling this diffusion. By providing turnkey infrastructure, core routers, traffic gateways, and 5G networks, these companies ensure that the hardware and software underlying new digital environments embed the same logics of inspection and control that define the Chinese model. This makes Beijing’s digital governance framework not just a domestic fixture but an exportable package, bundled with financing through the Digital Silk Road initiative. The export is both technical and political, shaping authoritarian states’ capacity to replicate China’s approach under the banner of sovereignty and “information security.”

The effect is a gradual normalization of state-mediated connectivity. Countries adopting GFW-style controls are not simply importing equipment; they are adopting a philosophy that treats information as a threat vector rather than a public good. Over time, this fosters interoperability among authoritarian regimes, creating channels for knowledge transfer, intelligence sharing, and shared censorship protocols. The outcome is a fragmented, parallel internet sphere where repression is standardized and commercialized, with China as the principal vendor of both ideology and infrastructure.

Societal Impact and Resistance

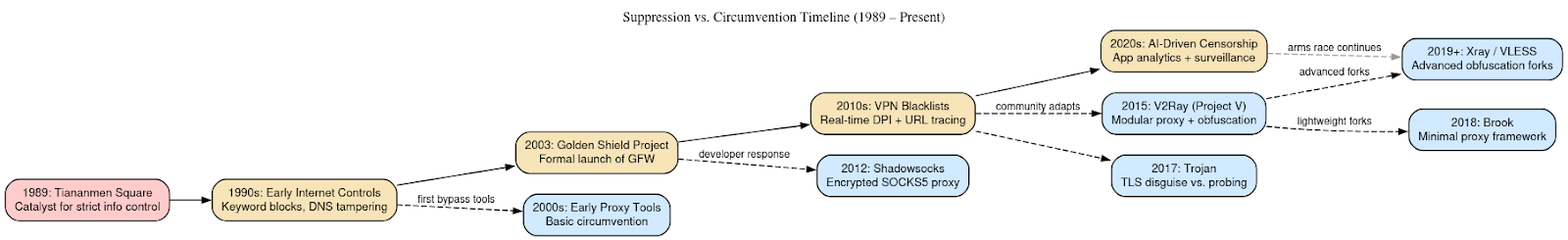

Since the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989, the Chinese Communist Party has treated the free flow of information as an existential threat to regime stability. The development of the Great Firewall must be understood in that context: it is not simply a security apparatus, but a continuation of the Party’s broader strategy to prevent mass mobilization by limiting access to ideas, narratives, and organizing tools. Over the decades, censorship has evolved from blunt blocking of foreign websites to a finely tuned system of VPN blacklists, URL tracebacks, and application-level analytics. These capabilities allow authorities to correlate individual users with dissent behavior in near-real-time, ensuring that politically sensitive searches, conversations, and digital gatherings are identified and neutralized before they can coalesce into movements. In effect, the firewall transforms the internet into an extension of the state’s security services, eroding anonymity and embedding surveillance into the mundane acts of browsing, messaging, or sharing.

Yet despite this pervasive control, resistance is both persistent and adaptive. Beginning with early proxy experiments in the 2000s, Chinese developers themselves have been central to the creation of circumvention tools. Shadowsocks, created in 2012 by a developer known as clowwindy, pioneered lightweight encrypted proxying that could slip past deep packet inspection. When Shadowsocks nodes began to be actively targeted, the community iterated with V2Ray (Project V), a modular platform with multiple transport protocols and obfuscation layers. This in turn inspired Trojan, which disguises proxy traffic as ordinary TLS to resist probing, and later Brook and Xray, forks that pushed further into stealth and flexibility. Each of these tools originated within Chinese coding circles, highlighting how resistance emerges from inside the very environment being controlled.

Culturally, dissent also manifests in creative forms. Social commentary critical of censorship and the Party circulates widely on Weibo, Bilibili, and WeChat before deletion, often employing satire, homophones, memes, or coded references to evade keyword filters. These “edge-ball” expressions illustrate both the limits of algorithmic censorship and the cultural resilience of Chinese netizens. Meanwhile, diaspora communities amplify resistance by publishing bypass techniques, hosting mirrors of blocked content, and maintaining repositories of circumvention code on platforms like GitHub, ensuring knowledge is never entirely erased inside the firewall.

The interplay between suppression and resistance thus produces an ongoing arms race. Each new round of GFW countermeasures provokes new tools, tactics, and cultural adaptations. While the firewall is formidable, it paradoxically nurtures an oppositional ecosystem that continually innovates around its constraints. Far from extinguishing dissent, the system creates a feedback loop of repression and resistance, embedding digital counterculture as a permanent feature of Chinese society. The result is a paradox: the GFW sustains authoritarian control, yet at the same time guarantees the continual reinvention of the very forms of resistance it seeks to eradicate.

Strategic Positioning in Global Cyber Norms

China’s long-term vision is visible through its participation in multilateral forums such as the UN’s Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) on ICT security and the Belt and Road Initiative’s “Digital Silk Road.” These initiatives provide diplomatic cover for Beijing’s promotion of “internet sovereignty” as a legitimate model of governance. In practice, this means embedding the logic of the Great Firewall into international policy discourse, presenting it not as censorship or repression but as a sovereign right of states to regulate information flows within their borders.

At the UN level, Chinese representatives have consistently argued for norms that emphasize non-interference in domestic internet policies, deliberately contrasting this with historical Western advocacy for a “free and open” internet. By reframing censorship as an extension of sovereignty, Beijing attempts to normalize state control as a global principle, effectively insulating its own practices from critique while empowering other governments to follow suit. The Digital Silk Road, meanwhile, operationalizes these ideas by providing infrastructure, financing, and governance templates to partner countries. Through fiber optic cables, 5G buildouts, and “smart city” packages, China creates an export pathway for both technology and ideology, linking development assistance with the adoption of Beijing’s governance model.

This approach positions China as more than a participant in global internet governance, it casts Beijing as a rule-setter. By aligning economic incentives with political norms, China gradually shifts the Overton window of global digital policy. What once would have been viewed as authoritarian overreach is rebranded as legitimate digital self-determination, creating a parallel order where the GFW’s logic is not an exception but an accepted standard.

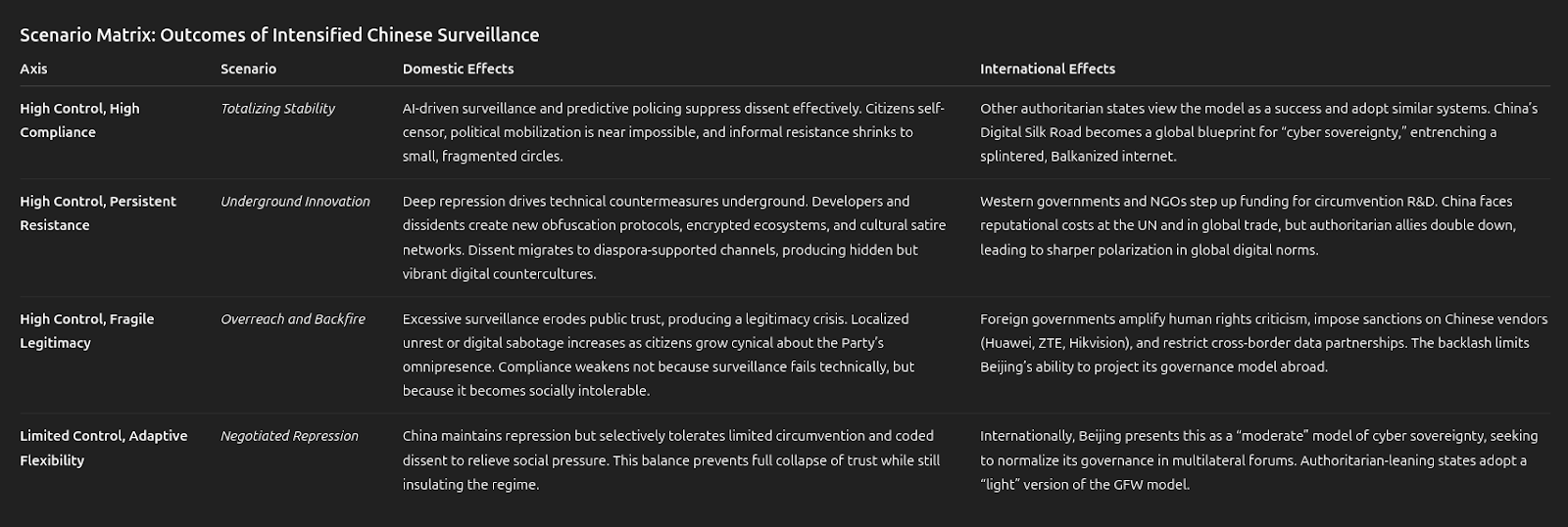

Future Resistance and Possible Outcomes of Intensified Surveillance

If China accelerates its trajectory toward deeper electronic surveillance and repression, the societal and geopolitical consequences are likely to manifest in both predictable and disruptive ways. At the domestic level, a more comprehensive fusion of AI-driven monitoring, predictive policing, and ubiquitous biometric collection would further entrench a climate of self-censorship and fear. The integration of surveillance with economic and social systems, already evident in the Social Credit framework, would amplify the daily costs of dissent, making deviation from state narratives punishable not only through arrest but through exclusion from essential services, employment, and mobility. In such an environment, formal opposition is unlikely to survive, but informal networks of coded communication and underground technological innovation could expand, creating a dual society where repression coexists with hidden circuits of resistance.

Historically, such intense monitoring regimes often produce unintended consequences. The more pervasive and intrusive the surveillance, the more it incentivizes citizens and developers to innovate countermeasures, ranging from obfuscated communication protocols to subtle forms of cultural satire and resistance. As seen with Shadowsocks and subsequent projects, the very act of suppression can cultivate technical expertise and solidarity networks among those targeted. If the state further escalates, resistance may shift from individual acts of circumvention toward collective forms of digital underground culture, diaspora-supported communication hubs, and encrypted parallel ecosystems that remain resilient precisely because they are decentralized and adaptive.

Externally, an increasingly repressive China risks catalyzing stronger responses from international actors. Multilateral organizations and democratic states may impose stricter technology export controls, sanctions on surveillance vendors, or coordinated support for civil-society circumvention efforts. At the same time, authoritarian-aligned states could take China’s model as a green light to expand their own controls, accelerating the Balkanization of the global internet. The result would be a sharper divide between “sovereign internets” that normalize repression and open networks that champion access, placing global institutions in a prolonged struggle over which model defines the standards of international governance.

The paradox, then, is that China’s tightening grip may secure short-term regime resilience at home while sowing the seeds of longer-term instability and resistance. As surveillance deepens, so too does the risk of overreach, where hyper-control undermines legitimacy and drives innovation in circumvention. On the world stage, Beijing’s hardening model could accelerate geopolitical polarization, forcing states to choose between integration into China’s censored, state-mediated sphere or alignment with more open, contested global frameworks. In both cases, the ultimate outcome is not stability, but fragility, a digital order defined less by uniform control than by the ceaseless negotiation between repression and resistance.

Conclusion

The Great Firewall is not just an internet control system, it is a pillar of China’s broader authoritarian toolkit. Its effectiveness lies in its quiet integration into daily digital life, shaping what can be seen, shared, or even imagined by hundreds of millions of citizens. Unlike blunt instruments of repression, the firewall functions with subtlety: it restricts choice by removing foreign competitors, embeds surveillance into domestic platforms, and fosters a normalized environment where censorship is an unremarkable fact of life. In this sense, the GFW is less a technical barrier than a lived reality, one that molds behavior and expectations in ways that reinforce the state’s authority.

Its design reflects China’s governing philosophy of centralized control, national data sovereignty, and cyber hegemony. By asserting that information space is equivalent to territorial space, the firewall operationalizes Beijing’s belief that sovereignty extends to the digital domain. The system’s modular architecture, spanning deep packet inspection, SNI filtering, proxy interception, and state-managed content platforms, embodies a deliberate strategy to consolidate both power and legitimacy. It is not merely defensive but expansive: a mechanism for shaping global discourse, setting technical standards, and projecting influence abroad through the export of both infrastructure and ideology.

The evidence parsed from this leak lays bare the breadth and ambition of that vision. At home, the firewall enforces compliance and blunts dissent, ensuring that political stability is reinforced through technological design. Abroad, it provides a model for regimes seeking to replicate China’s balance of control and growth, creating a coalition of states aligned around the principles of cyber sovereignty. Taken together, the GFW is less an isolated technology than it is a strategic doctrine, one that defines China’s path toward digital authoritarianism and seeks to normalize it as a global standard.