EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

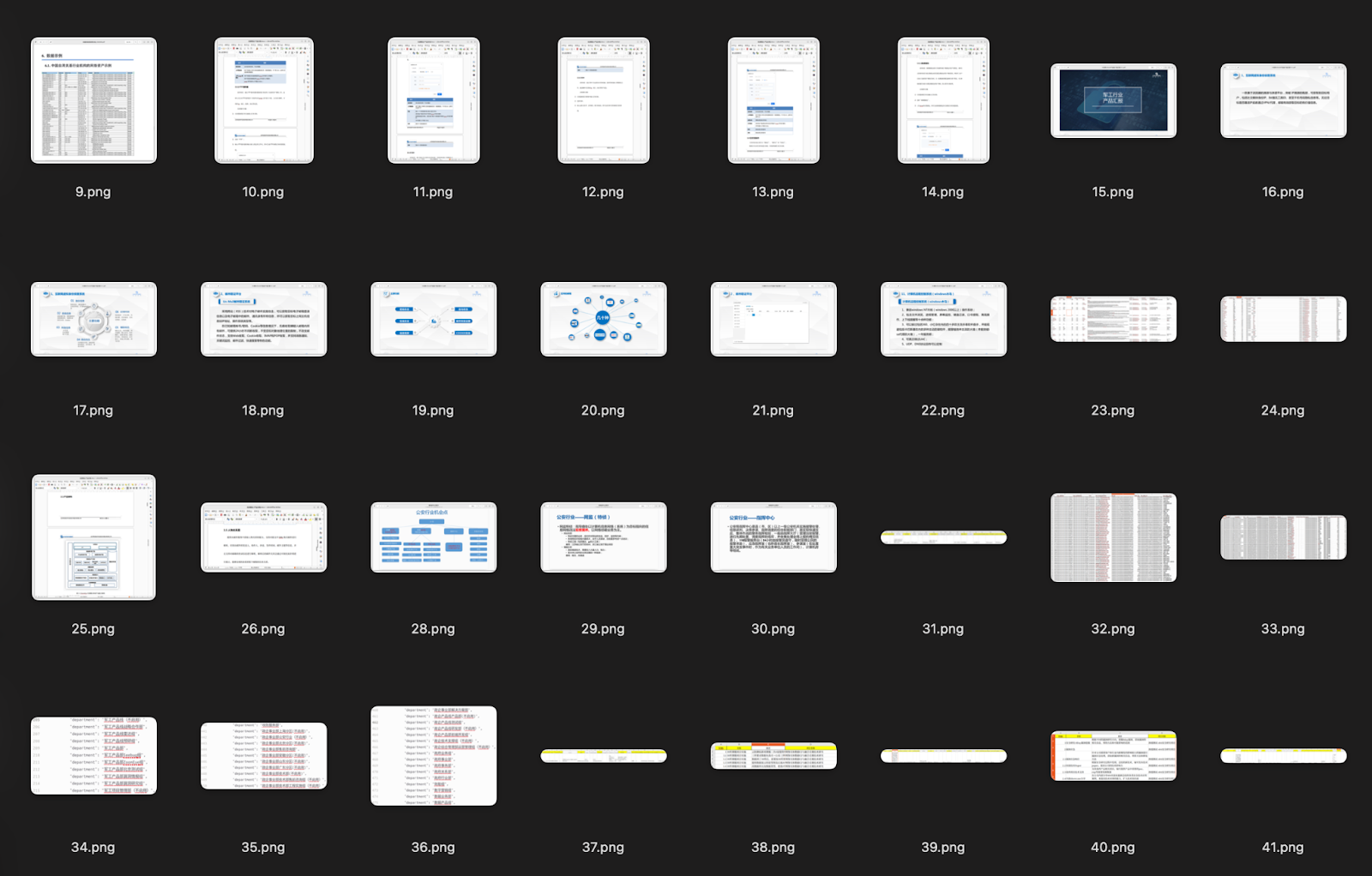

In November of 2025, an allegedly massive leak of data from Chinese company “KnownSec” was posted to a github account. The initial leak was covered by Wired Magazine, and a few other outlets. The leak has since been pulled off of Github and downloaded by very few, and of those few who gained access, only one uploaded 65 documents as a primer to the leak elsewhere for others to see. DTI was able to get the 65 document images and this report is derived from this slice of a much larger leak that is out there but not available.

On December 31 2025, platform and threat intelligence company Resecurity published an excellent analysis of the full leak. As we’ve been working through the 60+ available screenshots from the leak since early November, Resecurity’s post provides additional context in a few areas, especially targeting, that compliment the depth to which we analyzed Knownsec’s technical capabilities.

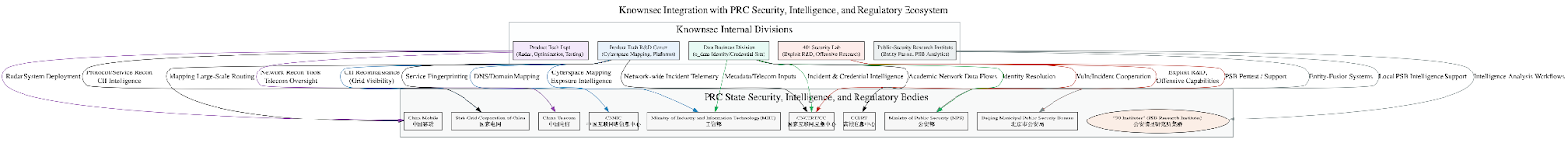

Ostensibly, KnownSec appeared to be just another security company, but this is only a half truth. In reality, like other reports we have written on Chinese firms, it has a shadow organization that works for the PLA, MSS, and the organs of the Chinese security state. This leak exposes a state-aligned cyber contractor that operates far beyond the role of a typical cybersecurity vendor. Its internal documents, product manuals, and data repositories show a company engineered to support Chinese national security, intelligence, and military objectives. Tools like ZoomEye and the Critical Infrastructure Target Library give China a global reconnaissance system that catalogs millions of foreign IPs, domains, and organizations mapped by sector, geography, and strategic value. Massive datasets containing real names, ID numbers, mobile phones, emails, and credentials allow Knownsec and its government clients to correlate infrastructure with people, enabling rapid deanonymization, targeting, and social engineering.

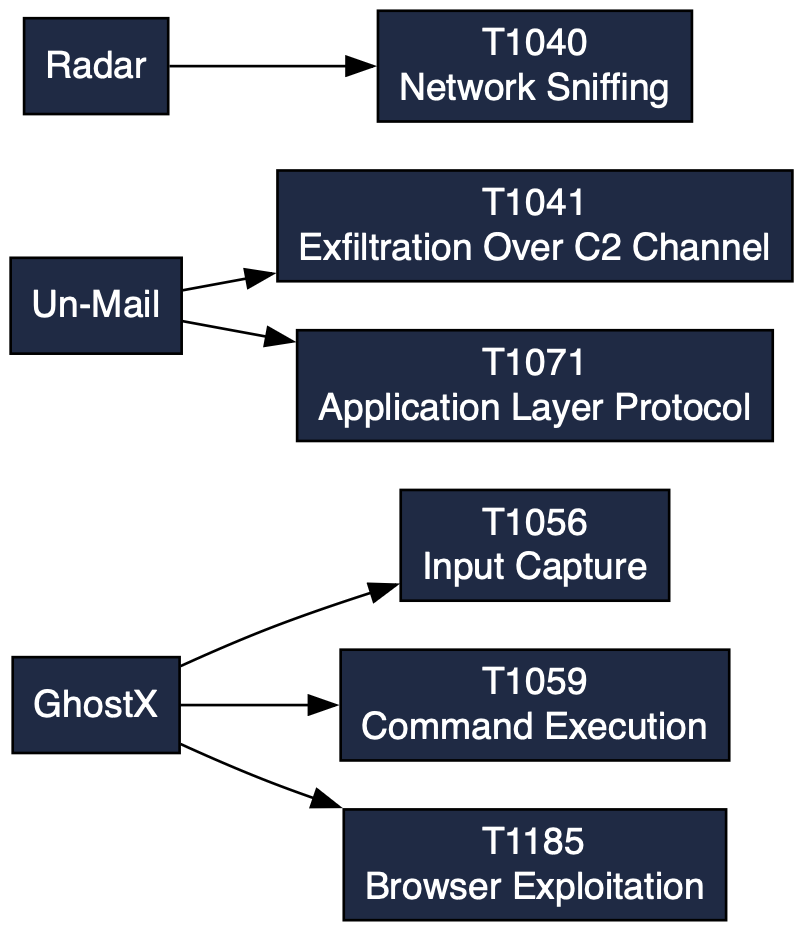

On top of this data foundation, Knownsec’s offensive products; GhostX, Un-Mail, and Passive Radar purport to provide a full intrusion and surveillance pipeline. GhostX delivers browser exploitation, routing manipulation, credential theft, and endpoint monitoring. Un-Mail enables covert takeover and continuous exfiltration of email accounts across major global providers. Passive Radar ingests PCAP data via local uploads, FTP, or SSH to reconstruct internal network topologies, user communication patterns, and service inventories. These tools work together to support long-term access, DNS hijack, admin takeover, and infrastructure control across foreign government, telecom, financial, and energy networks.

Organizational charts, customer lists, and internal briefings reveal Knownsec’s primary clients as Public Security Bureaus, defense research institutes, and likely the MSS, positioning it within China’s industrialized cyber-operations ecosystem. Its products are marketed directly to law enforcement and military customers, with teams explicitly labeled for “military industry,” “intelligence,” and “public-security support.” The leaked data shows a vertically integrated espionage stack for reconnaissance, exploitation, collection, and persistence, designed for both domestic surveillance and foreign intelligence operations, making Knownsec a central enabler of China’s modern cyber strategy.

Background

Knownsec (知道创宇), headquartered in Beijing, presents itself to the outside world as a familiar figure in the Chinese cybersecurity landscape, a company selling vulnerability assessments, penetration testing, and defensive solutions. It has long been framed as one of the country’s “white-hat” pillars, a firm dedicated to patching security gaps and strengthening networks. But the leaked internal documents, product manuals, work breakdown structure (WBS) project sheets, personnel directories, and vast infrastructure datasets tell a much more complex and far more consequential story. Beneath its public branding, Knownsec operates as an offensive intelligence contractor whose day-to-day work aligns directly with the operational needs of China’s security and military apparatus.

In practice, Knownsec functions within a tight constellation of state-aligned cyber contractors, a network that includes outfits like 404 Lab (internal to Knownsec) , Qi-An-Xin, Venustech, and i-SOON (安洵). These entities form a parallel ecosystem to China’s formal intelligence services, separate on paper, but woven into the broader machinery of state surveillance and cyberespionage. Together, they develop and maintain the tools, datasets, and capabilities required for large-scale identity tracking, offensive reconnaissance, infrastructure enumeration, and targeted intrusion. What sets Knownsec apart within this constellation is the degree of integration seen across its product lines: it does not merely produce one tool or one dataset, but rather an entire operational pipeline spanning discovery, exploitation, reconnaissance, persistence, and human-layer correlation.

The leaked materials reveal that Knownsec maintains some of the most extensive foreign targeting datasets yet seen in a contractor leak, covering Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, India, and multiple Western nations. Its clients include Public Security Bureaus at the provincial and national levels, defense research institutes, and intelligence-adjacent technical units. The company’s organizational charts and internal communications make clear that these relationships are not incidental; they are foundational to Knownsec’s business model and technical direction. In this light, Knownsec emerges not as a private security firm in the Western sense, but as a core node in China’s contractor-driven cyber state, a strategic architecture in which commercial entities serve as the research, development, and operational arms of state cyber power.

ACTOR TAXONOMY

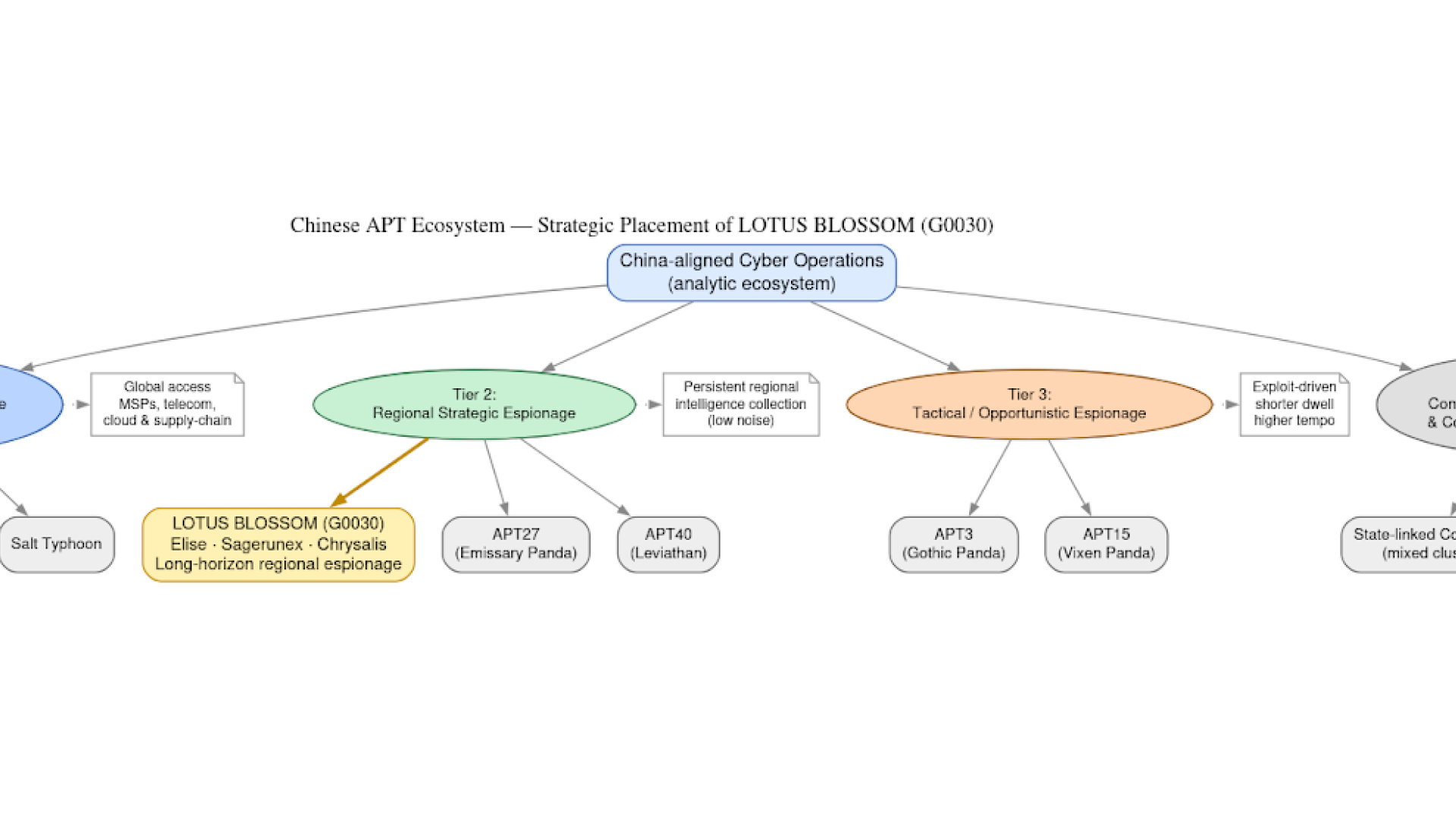

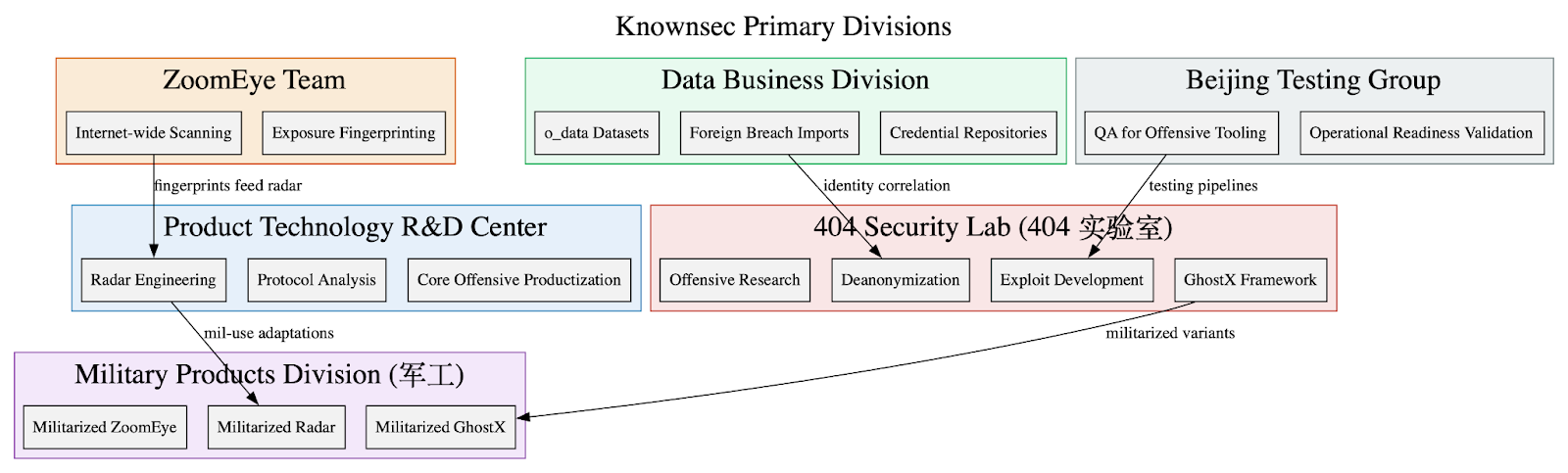

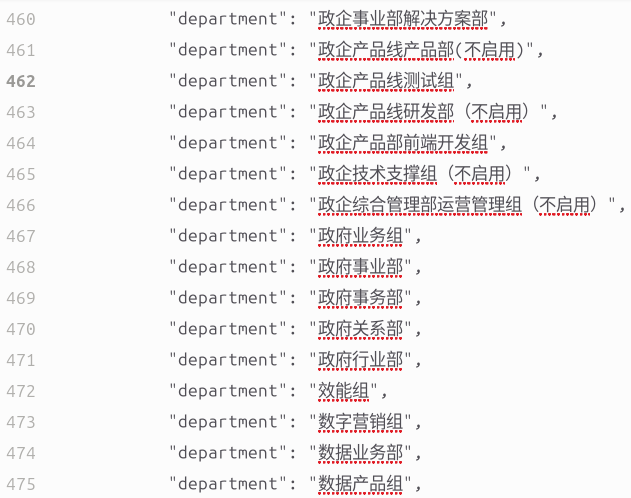

Organizational Structure

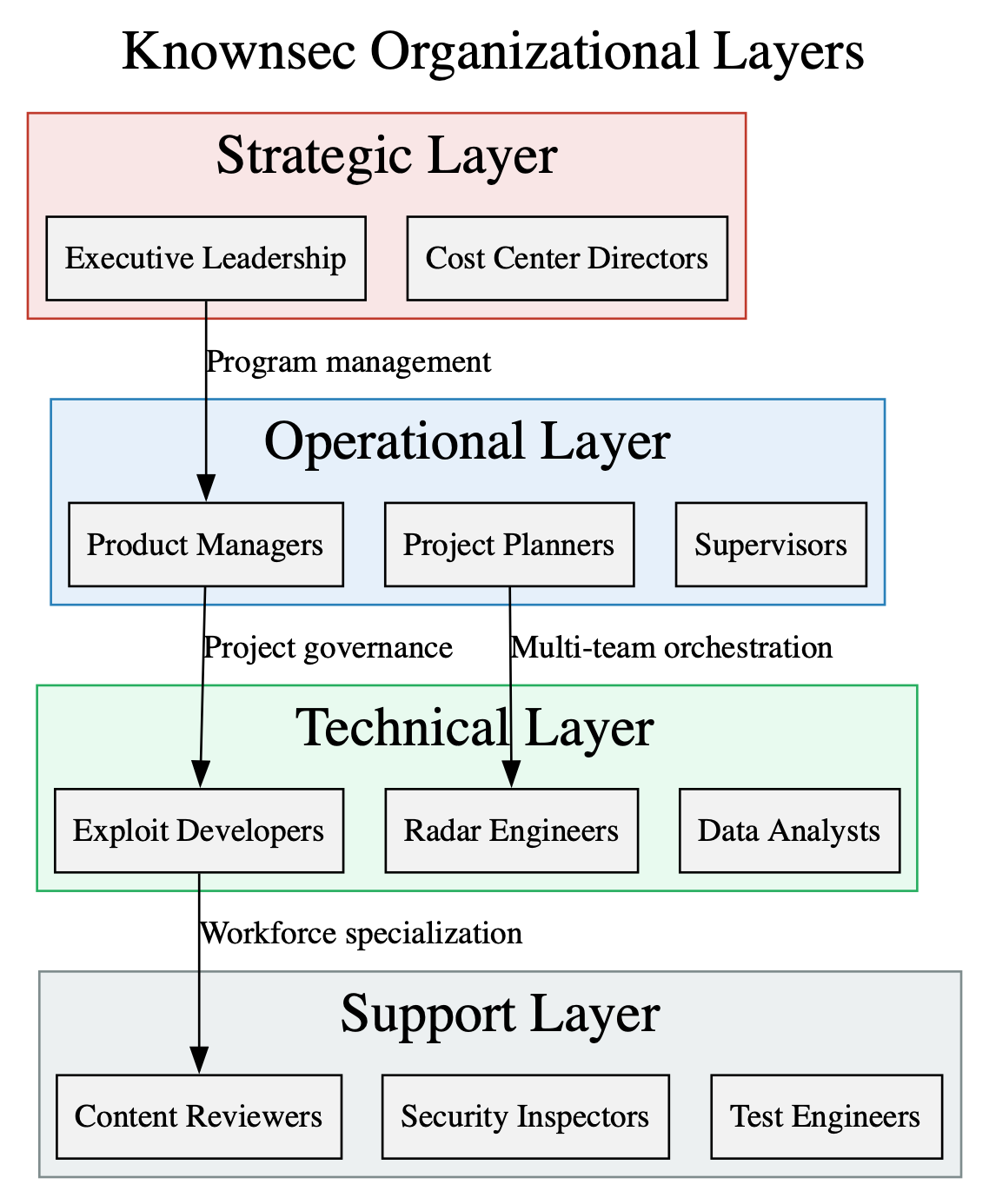

Knownsec’s internal architecture per this dump, resembles less a commercial technology company and far more a defense integrator calibrated to state needs. The organizational hierarchy is sharply defined, layered, and optimized for the production of offensive cyber capabilities. Each division has a narrowly tailored mandate that fits into a larger operational machine, an arrangement that mirrors the compartmentalization and task specialization typical of state-sponsored research institutes and weapons contractors.

At the technical core is the 404 Security Lab (404 实验室), a unit responsible for offensive research, exploitation development, and deanonymization, including stewardship of the GhostX tooling family. This is the engine room where browser exploits, network manipulation modules, and deanonymization workflows are built. Surrounding it is the Product Technology R&D Center, which transforms raw offensive ideas into stable, deployable products (most notably Passive Radar), protocol-analysis frameworks, and related reconnaissance systems. Feeding these tools is the Data Business Division, which curates massive datasets, foreign breach archives, and credential repositories, effectively forming the human intelligence layer of Knownsec’s cyber operations. Where state-aligned priorities shift toward military readiness or battlefield cyber support, the Military Products Division (军工) adapts and reconfigures Knownsec’s core technologies – ZoomEye, Radar, GhostX – into militarized variants suitable for defense research institutes and specialized units. Meanwhile, the ZoomEye Team maintains the company’s most publicly recognizable asset: a continuous internet-wide scanning and exposure fingerprinting platform. Once all these tools are built, the Beijing Testing Group ensures they meet stability and operational-readiness requirements before deployment to customers.

This hierarchy fractures into distinct functional strata. At the strategic layer, executive leadership and cost-center directors coordinate funding, long-term planning, and alignment with state-customer requirements. The operational layer, project managers, planners, and supervisors – turns those directives into executable work, assigning tasks across teams and ensuring compliance with delivery timelines. The technical layer comprises exploit developers, reverse engineers, protocol analysts, “radar specialists” (aka those working with the platform dealing with internet scale sensing/detection), and data scientists, the hands-on specialists who build Knownsec’s offensive capabilities. Beneath them, the support layer handles content review, security inspection, documentation, and QA critical roles that ensure continuity and polish across the toolchain.

Viewed holistically, the internal structure mirrors the logic of a Chinese cyber-weapons manufacturer: program management offices overseeing multi-year development tracks; governance systems controlling scope, deliverables, and interdepartmental dependencies; and specialized teams that collaborate, integrate, and refine capabilities in parallel. The result is not a loose assemblage of researchers, but a multi-team, multi-layered production line, where offensive tools move from concept to deployment with the discipline and scale of an industrial operation aligned to national strategic priorities.

Role Characterization

Knownsec’s internal personnel structure forms a tiered hierarchy that resembles the command-and-control model of a state-linked defense contractor rather than a commercial cybersecurity vendor. At the top sits the strategic layer, composed of executive leadership, business-unit heads, and cost-center directors who set long-term priorities, allocate resources, and ensure alignment with the missions of Public Security Bureaus, military research institutes, and other government stakeholders. Their role is not merely administrative; they define the operational direction of Knownsec’s offensive tooling, selecting which capabilities to develop, which foreign networks to map, and which datasets to prioritize for correlation.

Beneath them churns the operational layer, populated by project managers, planners, and supervisors responsible for translating strategic objectives into actionable engineering programs. These individuals oversee WBS tasking, cross-team coordination, and delivery timelines. They determine how GhostX (“GhostX Framework” offensive cyber platform) modules integrate with Un-Mail (email interception tool), how Passive Radar ingests or parses PCAP data, and how TargetDB updates synchronize with ZoomEye (search engine) output. In effect, they are the connective tissue that binds Knownsec’s sprawling toolchain into a coherent, predictable development pipeline.

The technical layer of exploit developers, radar engineers, data analysts, infrastructure specialists is the skilled workforce that turns those plans into operational capabilities. These teams build the browser exploitation chains, protocol-analysis engines, deanonymization classifiers, and dataset-correlation tools that make Knownsec’s products function as integrated intrusion systems. Supporting them is a broad support layer of content reviewers, security inspectors, and test engineers who ensure data quality, operational safety, and readiness for customer deployment. This division of labor reinforces Knownsec’s resemblance to a Chinese cyber defense integrator, featuring programmatic control structures, specialized technical teams, and multi-layer orchestration designed to reliably produce offensive cyber capabilities at scale.

FULL CAPABILITY ANALYSIS

Global Reconnaissance Layer

Knownsec’s offensive operations begin with a global reconnaissance layer, a foundation built on visibility rather than exploitation. At the heart of this layer is ZoomEye, the company’s internet-wide scanning and fingerprinting platform. Externally marketed as a security research tool, ZoomEye in practice functions as a persistent intelligence sensor grid, one capable of mapping the exposed surfaces of entire nations. Unlike Shodan or FOFA, which rely on hybrid community indexing and slower crawl cycles, ZoomEye conducts full IPv4-space scanning, generating a continuously refreshed portrait of devices, services, and vulnerabilities across the global internet.

ZoomEye’s detection capabilities are unusually granular. Its internal documentation highlights a library of 40,000+ component fingerprints, allowing it to identify not just common servers but also specialized firewalls, industrial controllers, VPN concentrators, and software versions critical for exploitation targeting. The platform recrawls its indexed universe every 7–10 days, making its data nearly real-time, a crucial requirement for Chinese security organs that depend on freshness for both censorship enforcement and foreign operations. Every newly exposed port, misconfigured appliance, or unpatched system becomes visible to Knownsec’s analysts before many national CERTs are even aware of the shift.

The true power of ZoomEye emerges in its integration with Knownsec’s TargetDB (关基目标库: Key Target Library), a classified-style infrastructure database that cross-references ZoomEye results with sector, geographic, and organizational metadata. Raw IPs and banners from ZoomEye become tagged entries in a structured intelligence map identifying which systems belong to ministries, power companies, telecom operators, banks, or military units. In this way, ZoomEye doesn’t merely scan the internet; it prioritizes it, funneling raw exposure intelligence directly into China’s national-level targeting workflows.

ZoomEye

A global cyberspace search engine equivalent to Shodan/FOFA but with:

- Full IPv4-space scanning

- 40,000+ component fingerprints

- Rapid recrawl cycles (7–10 days)

- Cross-integration with TargetDB

TargetDB (关基目标库)

Knownsec’s TargetDB (关基目标库) is the analytical backbone of its reconnaissance capability, an immense, curated intelligence repository that transforms raw internet data into a structured map of global critical infrastructure. Far more than a simple asset index, TargetDB resembles a state-run targeting platform: a system designed to catalog, classify, and prioritize foreign networks according to strategic value. The scale alone is staggering. Internal documentation lists 24,241 organizations, 378,942,040 IP addresses, and 3,482,468 domains, all tagged with metadata that places them within specific industries, national sectors, and operational categories. These entries span 26 geographic regions, covering not only China’s immediate neighbors but also major economies and political rivals across Asia, Europe, and the West.

What gives TargetDB its strategic potency is the precision of its annotations. Each organization and network block is mapped to sector designations such as military, military-industrial, government ministries, telecom operators, energy providers, financial institutions, transportation networks, media outlets, and educational institutions. This transforms an anonymous IP range into a clearly identified target: a ministry of foreign affairs server in Tokyo, a regional power-grid node in Kaohsiung, a financial-trading gateway in Mumbai, or a satellite uplink belonging to a Korean telecom. The database does not simply list assets; it assigns them meaning, aligning infrastructure with strategic objectives and intelligence requirements.

In practice, TargetDB functions as a foreign-target prioritization engine, allowing Chinese state clients to focus their operations on the most consequential systems. When paired with ZoomEye’s continuous scanning, TargetDB becomes a living intelligence reference that highlights newly exposed systems belonging to sensitive entities. This fusion of raw exposure data with organizational and geopolitical context gives Knownsec and its customers a ready-made blueprint for cyber campaigns identifying who matters, where they are located, and precisely which services are vulnerable at any given moment.

The Critical Infrastructure Target Library contains:

- 24,241 organizations

- 378,942,040 classified IPs

- 3,482,468 domains

- Sector mappings across 26 geographic regions

It annotates:

- Military units

- Government ministries

- Telecom operators

- Energy companies

- Financial institutions

- Media and education networks

Data Lake (o_data_*)

Knownsec’s o_data_ data lake* represents one of the most revealing and troubling components of the entire leak. Beneath the polished surface of its security products lies a sprawling, carefully indexed archive of global breach data, sourced from criminal markets, prior compromises, open leaks, and internal acquisitions. These datasets include LinkedIn collections from Brazil and South Africa, Taiwan Yahoo account dumps, Indian Facebook user sets, and extensive Chinese national datasets ranging from railway passenger manifests to banking records and ID-card tables. Layered atop this are telecom subscriber databases, often containing phone numbers, IMSI/IMEI identifiers, addresses, and account metadata. Each dataset is catalogued with schema details including username, password, id_card, mobile, email, real_name, address, investment_style, and more, making the data lake a high-resolution, global directory of human digital traces.

Within Knownsec’s operational ecosystem, this data lake is not a passive archive; it functions as an identity-correlation engine. When a TargetDB entry identifies an exposed service or a ZoomEye scan reveals a misconfigured endpoint, analysts can pivot into the o_data_* records to uncover the real-world individuals associated with that IP, email, or domain. A VPN endpoint in Osaka becomes a person with a name, mobile number, and password reuse history. A Taiwanese banking server becomes an enumerated list of employees with matching emails, credential pairs, and personal details. These correlations enable credential replay attacks, account takeover attempts, and highly tailored social-engineering operations long before any exploit payload is deployed.

But the most powerful function of the data lake is its role in deanonymization. Modern cyber operations often hinge on identifying the human behind the machine, and the o_data_* archives allow Knownsec and by extension its state customers to strip away anonymity across borders. By linking breached credentials, phone numbers, and identity documents to technical infrastructure, the data lake fuels a range of offensive workflows: spearphishing campaigns, targeted malware delivery, behavioral profiling, and covert influence operations. In effect, the o_data_* collection serves as the human-intelligence layer of Knownsec’s cyber apparatus, turning scattered breach records into a structured intelligence resource that drives foreign espionage, domestic tracking, and precision targeting at scale.

A massive archive of global breach data:

- LinkedIn Brazil, South Africa

- Taiwan Yahoo email/password datasets

- Indian Facebook sets

- Chinese national ID/railway/banking data

- Telecom subscriber DBs

Purpose:

- Correlate human identities

- Enable credential replay

- Enable deanonymization

- Power targeted phishing and social engineering

Access Layer

Knownsec’s Access Layer is embodied most clearly in its flagship offensive toolkit, GhostX, a system designed not merely to breach endpoints but to reduce, reconstruct, and ultimately control digital identity. GhostX operates at the intersection of browser exploitation, network manipulation, and host persistence. It begins with browser fingerprinting, gathering granular details, plugins, fonts, extensions, power telemetry, and rendering quirks to create a durable identity signature that follows a user across VPNs, proxies, and devices. Once a target is profiled, GhostX can be set to escalate into active compromise: extracting browser-stored passwords, siphoning cookies and session tokens, and deploying keylogging modules that capture input in real time. These capabilities allow operators to pivot immediately into email accounts, internal dashboards, or social platforms without requiring traditional exploit chains.

But GhostX’s reach extends well beyond the endpoint. The suite includes tools for internal service identification, mapping what the compromised machine can see inside a network database, ports, admin interfaces, intranet portals, and shared resources. From there, GhostX can manipulate the network environment itself through routing attacks and DNS hijacking, redirecting traffic or impersonating internal systems. The ability to create new admin accounts on routers or internal services turns a momentary foothold into a durable position within the victim’s infrastructure, enabling stealthy lateral movement or long-term monitoring. Operators can also invoke remote command execution, screenshot capture, and webpage cloning, giving GhostX a Swiss-army-knife versatility normally found in high-end, nation-state-grade intrusion platforms.

Central to GhostX’s design is its suite of anti-forensic mechanisms and techniques such as code mixing, behavior shaping, and signatureless execution explicitly described in internal product briefs. These features aim to frustrate defenders, slow incident response, and complicate attribution. When combined, GhostX becomes a multi-vector exploitation and persistence framework, engineered to collapse anonymity, extract access, and maintain covert presence across both user endpoints and network infrastructure. It is a foundational component of Knownsec’s offensive cycle, bridging the gap between reconnaissance and deeper operational penetration.

GhostX Virtual Identity Reduction & Exploitation Suite

Capabilities include:

- Browser fingerprinting

- Password extraction

- Cookie and credential theft

- Keylogging

- Website cloning

- Screenshot monitoring

- Internal service identification

- Routing manipulation

- DNS hijacking

- Admin user creation

- Command execution

- Anti-forensics (code mixing, signature evasion)

Un-Mail Webmail Takeover & Persistent Collection

Knownsec’s Un-Mail platform is the company’s dedicated engine for webmail takeover and long-term communications exploitation, effectively turning inboxes into intelligence feeds. Unlike traditional phishing tools or standalone password stealers, Un-Mail is built to compromise webmail ecosystems at the application layer, beginning with XSS-based exploitation of major mail portals. These injection points allow attackers to intercept login sessions, capture live session tokens, or inject malicious scripts directly into a victim’s browser workflow. Once access is established, Un-Mail seamlessly transitions into session hijacking and cookie replay, bypassing MFA or password-change events and ensuring operators maintain continuous entry even as the victim continues to use their account.

The platform’s most powerful capability is its ability to perform IMAP/POP mailbox replication, silently downloading the entire mailbox including archived, deleted, or years-old communications into a local datastore under operator control. This “first sync” is typically followed by ongoing incremental collection, with Un-Mail monitoring for new messages and exfiltrating them in real time. Operators can configure keyword triggers for sensitive terms, automate alerts when certain contacts communicate, and selectively forward or clone messages without user visibility. Internal product slides emphasize full inbox exfiltration and customizable monitoring dashboards, indicating a mature COMINT-oriented architecture rather than a simple webmail attack script.

Un-Mail’s reach is expanded by its cross-provider compatibility, with explicit support for Gmail, Outlook/Hotmail, Yahoo, AOL, and major Chinese providers such as 163, 126, TOM, and Yeah.net. This broad compatibility allows Knownsec and its state clients to conduct communications intelligence collection across national borders, harvesting diplomatic correspondence, corporate strategy emails, and internal government mails for targeting purposes. The result is a tool purpose-built for persistent surveillance, supporting intelligence requirements ranging from domestic monitoring to foreign espionage, further evidence that Knownsec’s operational mission extends deep into offensive state-cyber tradecraft.

Capabilities:

- XSS exploitation of webmail portals

- Session hijacking

- Cookie replay

- IMAP/POP mailbox replication

- Full inbox exfiltration

- Real-time keyword monitoring

- Cross-provider compatibility (Gmail, Outlook, Yahoo, 163, 126, etc.)

This enables communications intelligence collection (COMINT) across national borders.

Internal Network Discovery

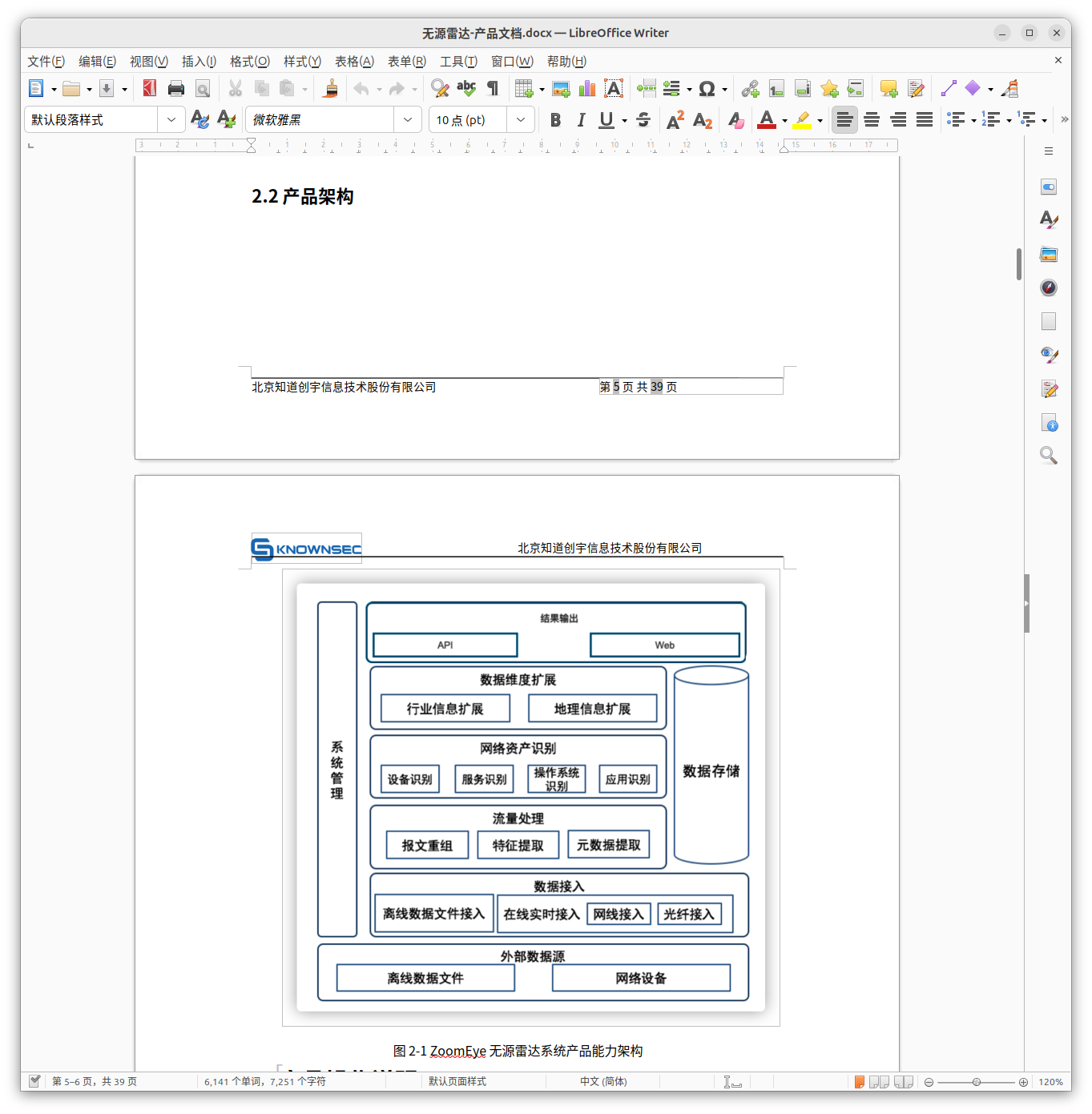

Knownsec’s Passive Radar (无源雷达) is designed for the phase immediately following initial access, when the operational priority shifts from intrusion to comprehension. While tools such as GhostX focus on endpoints and Un-Mail captures communications, Passive Radar illuminates the internal network environment those systems inhabit. Its purpose is not exploitation in isolation, but the reconstruction of the operational terrain inside a compromised organization.

Unlike active scanners that generate detectable traffic, Passive Radar relies exclusively on the ingestion and analysis of packet capture (PCAP) data. This passive approach allows operators to observe a network as it actually behaves, without altering traffic patterns or triggering defensive controls. The system accepts PCAPs through three primary ingestion paths: direct offline uploads, remote retrieval via FTP, and secure acquisition over SSH. These mechanisms allow traffic to be sourced from compromised servers, misconfigured storage systems, network taps, or siphoned repositories without requiring live interaction with the target environment.

Once ingested, Passive Radar automatically extracts and classifies the network’s technical structure. It identifies IP addressing schemes, port usage, protocol signatures, service banners, device types, and traffic flows, assembling these elements into a coherent model of internal communications. By correlating flows over time, the platform reveals which systems communicate persistently, how authentication and directory services are organized, where data is aggregated or forwarded, and which services function as internal chokepoints.

This process exposes high-value internal assets that are often invisible from the perimeter: domain controllers, mail gateways, internal content-management systems, financial platforms, and management interfaces. Behavioral flow analysis highlights trust relationships, reused credentials, and open administrative paths that can be leveraged for lateral movement. Device classification further identifies unmanaged servers, weakly configured firewalls, and embedded or IoT systems that present escalation opportunities.

Through this transformation of raw packet data into structured internal intelligence, Passive Radar provides the situational awareness required to move beyond an initial foothold and toward sustained control of a target network.

Passive Radar (无源雷达)

The strategic significance of Passive Radar lies not merely in what it observes, but in how it collapses uncertainty for offensive operators. By deriving intelligence from real traffic rather than inferred exposure, the platform reveals how a network truly functions under normal conditions. This traffic-derived perspective exposes dependencies, trust boundaries, and operational habits that conventional vulnerability scanning cannot reliably detect.

Viewed through an offensive lens, Passive Radar functions as an internal reconnaissance and targeting system. Its outputs identify viable lateral-movement routes, uncover unencrypted administrative channels, and surface shared authentication paths that enable quiet expansion through a network. Instead of probing for weaknesses, it allows operators to exploit the structure that already exists, reducing noise while increasing precision.

This capability is particularly valuable in state-aligned operations, where persistence, attribution control, and long-term access outweigh speed. Passive Radar turns captured network traffic into operational intelligence that supports methodical expansion, selective exploitation, and planned data extraction. In effect, it converts the interior of a victim network from an opaque risk space into a charted environment suitable for controlled maneuver.

For Knownsec’s government and military customers, Passive Radar serves the same role in cyberspace that reconnaissance and terrain analysis serve in conventional operations. It enables planners to study internal infrastructure, anticipate defensive responses, and design lateral movement and persistence strategies with confidence. In this sense, Passive Radar is not simply a security product, but a foundational intelligence capability that bridges access and dominance within the digital battlespace.

A PCAP-based internal situational awareness tool:

3 ingestion modes:

- Offline PCAP

- FTP

- SSH

Extracts:

- IPs

- Ports

- Protocols

- Behavioral flows

- Services

- Device types

Purpose:

- Map internal networks

- Identify critical hosts

- Reveal lateral-movement opportunities

- Build operational intelligence for deeper compromise

Persistence & Exfiltration Layer

Knownsec’s Persistence & Exfiltration Layer represents the phase of an operation where intrusion shifts from momentary access to steady, renewable intelligence collection. Once an endpoint or infrastructure node has been compromised through GhostX, Un-Mail, or Passive Radar–assisted lateral movement, Knownsec’s tooling activates a suite of mechanisms designed to keep the operator embedded indefinitely. At the user level, this includes keylogging and clipboard capture, which harvest credentials, sensitive text, and operational behavior with granular precision. These seemingly simple functions become powerful when combined with GhostX’s browser and routing manipulation: every password typed, every copied token, every pasted URL becomes part of the attacker’s internal map of the victim’s digital life.

Beyond user surveillance, Knownsec’s tools enforce persistence by manipulating the environment itself. Forced browsing modules can redirect users to attacker-controlled sites to refresh payloads or harvest updated cookies, while webshell interaction provides a remote backdoor for issuing commands and staging follow-up operations. The ability to perform DNS hijacking ensures long-term redirection and covert traffic interception, allowing Knownsec’s operators or their state clients to control access to internal or external resources without needing continuous endpoint presence. When this is combined with admin account creation on routers or internal network appliances, attackers gain durable infrastructure-level footholds that survive password changes, system updates, and even some forms of incident response.

Communication exfiltration remains a central pillar of Knownsec’s persistence strategy. Through Un-Mail, compromised inboxes can be synchronized via ongoing IMAP replication, creating a live copy of the user’s communications outside the victim network. New messages are silently collected, sensitive terms trigger alerts, and historical archives can be mined for strategic value. When all these elements operate together keystroke capture, environmental manipulation, infrastructure control, and communications replication they form a persistent intelligence foothold. This foothold is not just durable; it is regenerative, enabling long-term espionage, strategic monitoring, and operational leverage across months or even years, well after the initial compromise has been forgotten by the victim.

Includes:

- Keylogging

- Clipboard capture

- Forced browsing

- Webshell interaction

- DNS hijack for long-term redirection

- Admin account creation on routers

- IMAP-based ongoing mailbox replication

This creates persistent intelligence footholds.

OPSEC & Anti-Forensics

Knownsec’s toolchain incorporates a mature OPSEC and anti-forensics layer, reflecting the needs of an organization that expects its operations to face scrutiny from both corporate defenders and national incident-response teams. Rather than treating stealth as an afterthought, Knownsec designs its offensive tools to actively manipulate the investigative environment, reshaping the forensic trail and degrading the defender’s ability to reconstruct what happened. This begins with proxy chain deployment, allowing operators to route traffic through multilayered, frequently shifting intermediaries that obscure the true origin of commands, payloads, or callback traffic. By automating these routing changes, Knownsec ensures that attribution efforts are diluted across ranges of unrelated IP space.

Beyond network obfuscation, Knownsec incorporates behavior-shaping and code-mixing techniques, which alter how malicious scripts behave on compromised systems. Instead of producing predictable logs or recognizable execution patterns, operations are blended into normal system activity or fragmented across modules that only reveal their true function when combined under specific conditions. These methods frustrate heuristic detection and force analysts to piece together sequences of behavior that appear benign in isolation.

Perhaps most challenging for defenders is the emphasis on signatureless execution and anti-tracing modules, which remove or modify indicators that typically reveal compromise. Malware components are often polymorphic or dynamically assembled, leaving no stable signatures for endpoint security tools to match. Meanwhile, anti-tracing features interfere with monitoring hooks, logging frameworks, and analyst tools, making post-incident reconstruction incomplete or misleading. Together, these OPSEC and anti-forensic capabilities signal that Knownsec’s offensive products are built not only to infiltrate networks but to survive inside them, resisting detection long enough to achieve intelligence objectives and complicating attribution even after an intrusion is discovered.

Capabilities:

- Proxy chain deployment

- Behavior obfuscation

- Code mixing

- No-signature execution

- Anti-tracing modules

Designed to degrade defender and investigator visibility.

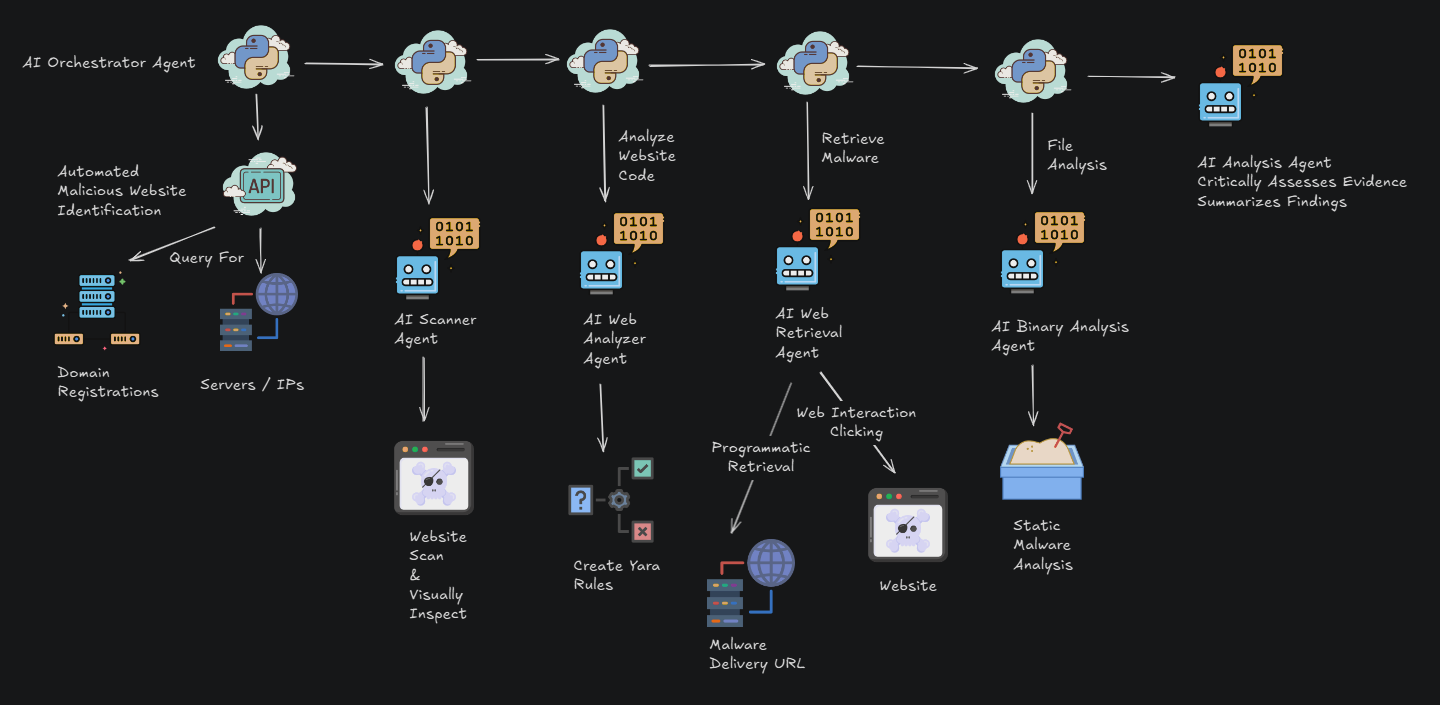

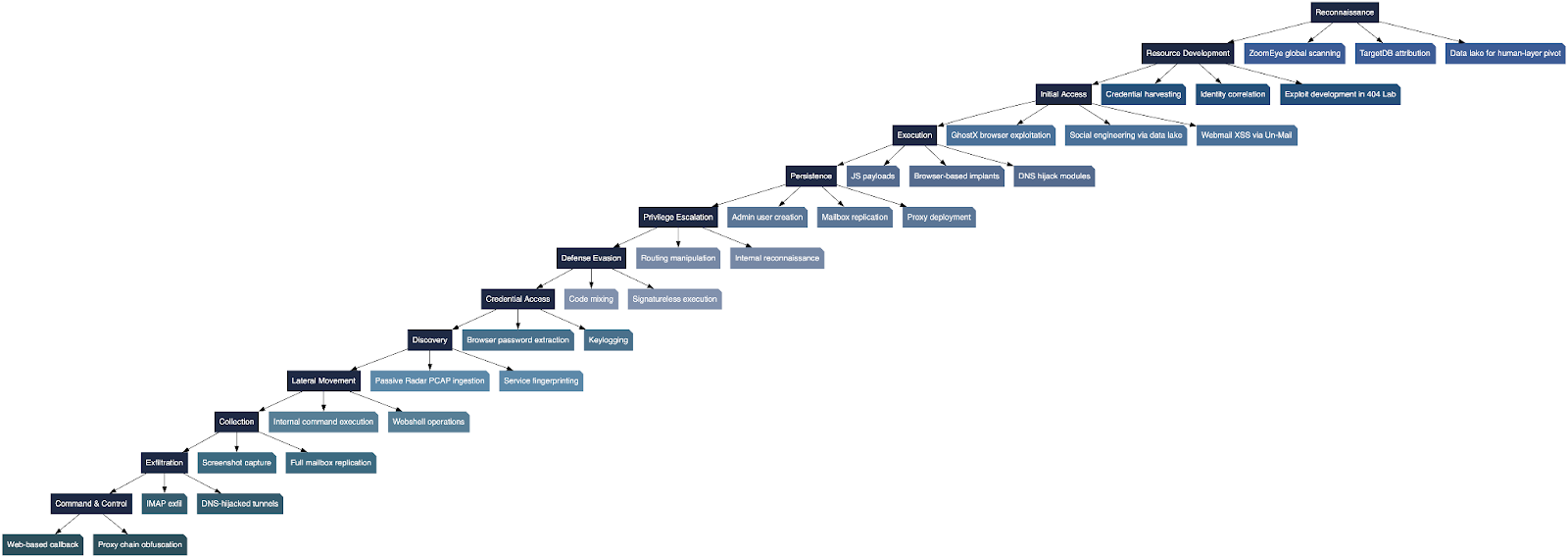

TRADECRAFT & TTPs

Knownsec’s operational workflow reflects a fully realized, contractor-engineered APT intrusion lifecycle, blending state objectives with commercial development discipline. What emerges from the leak is not a set of disconnected tools, but a coherent tactic-to-technology pipeline, where each stage of intrusion is supported by a purpose-built product or dataset. The tradecraft reads like a synthesis of China’s most capable threat actors APT31, APT41, Mustang Panda yet polished through a corporate engineering lens that emphasizes stability, modularity, and reuse across diverse missions.

The intrusion sequence begins with reconnaissance, powered by ZoomEye’s internet-wide scanning and the TargetDB attribution system, which labels millions of global IPs by organization, sector, and geopolitical relevance. Once a target is identified, Knownsec pivots into its human-layer intelligence using the o_data_* collections: massive breach datasets that reveal who operates which systems, how they authenticate, and which credentials or identities overlap across services. These datasets feed directly into resource development, where credential harvesting, identity correlation, and exploit development (largely through 404 Lab) prepare the ground for an intrusion tailored to the target’s technical and human profile.

Initial access is typically obtained through GhostX’s browser exploitation modules, social-engineering campaigns crafted through breach data, or Un-Mail’s XSS-based webmail compromise. Once inside, Knownsec’s operators transition smoothly into execution, deploying JavaScript payloads, browser implants, or DNS manipulation scripts to deepen footholds. The tooling then shifts into persistence mechanisms creating admin accounts on routers, setting up IMAP mailbox replication, and establishing proxy chains that ensure continued access even as environments shift.

From there, intrusions expand through privilege escalation and discovery, guided by routing manipulation and Passive Radar’s PCAP-derived intelligence to illuminate the structure of internal networks. Defense evasion occurs continuously through code mixing, signatureless execution, and behavioral obfuscation. Credential access is achieved via browser password extraction and keylogging, enabling lateral movement into systems that would otherwise require separate exploitation. As operators explore the victim environment, they perform service fingerprinting, internal command execution, and webshell interaction to propagate their influence.

Finally, intrusion objectives manifest through collection and exfiltration, with Knownsec tools capturing screenshots, siphoning mailboxes, and sending stolen data out via IMAP or DNS-hijacked channels. Command and control remains flexible and resilient, relying on web-based callbacks and multi-hop proxy chains that obscure operational origins. Taken together, this lifecycle reveals a level of integration rarely seen outside state intelligence services: a full-spectrum intrusion pipeline where reconnaissance, exploitation, persistence, and exfiltration are engineered as interoperable modules within a single contractor-driven ecosystem.

The Knownsec pipeline mirrors a modern APT intrusion lifecycle:

This aligns with APT31, APT41, Mustang Panda, but with a commercial-engineering polish.

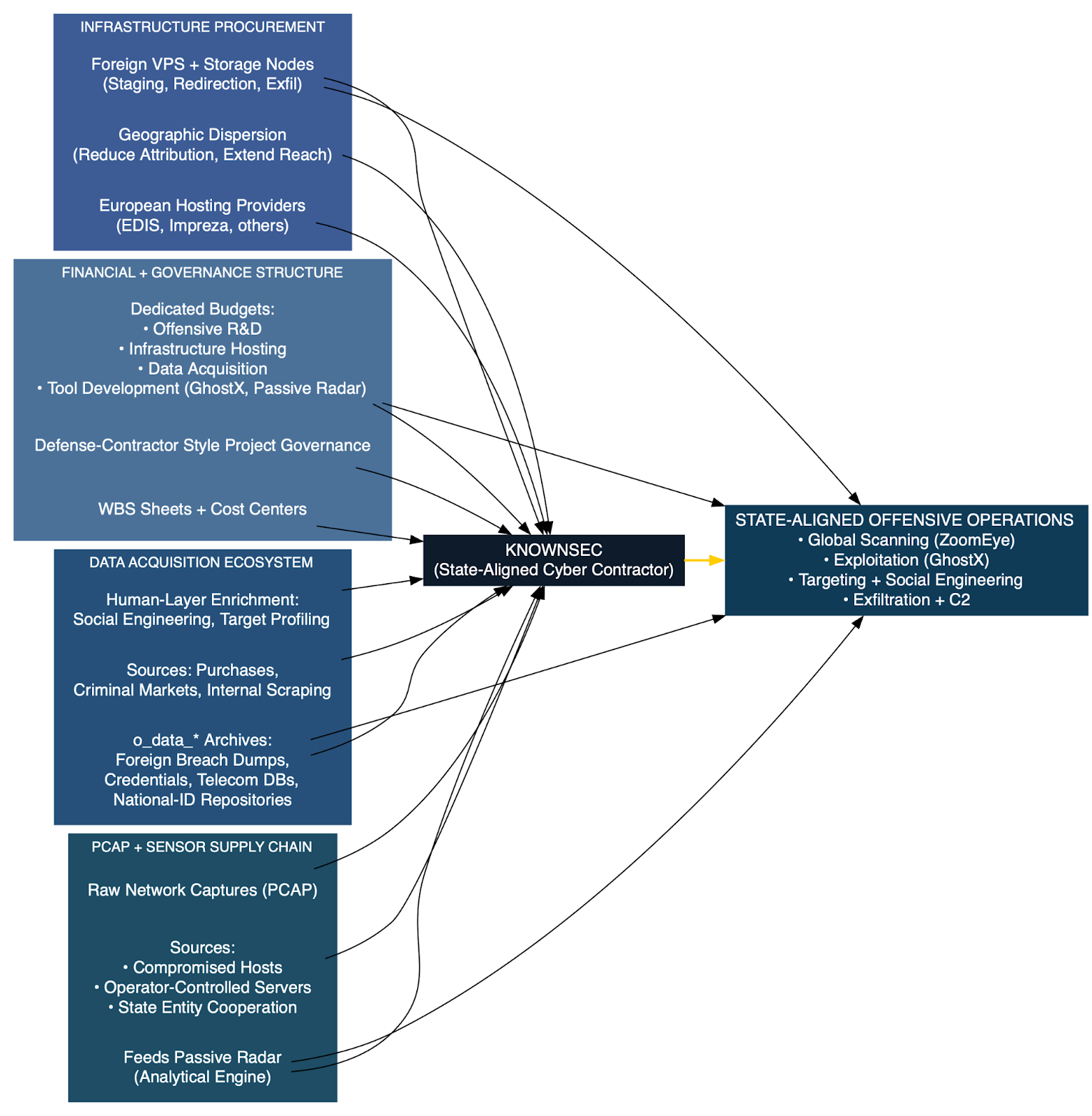

SUPPLY-CHAIN INTELLIGENCE

Knownsec’s operational footprint is supported by a sophisticated and multilayered supply chain, one that mirrors the procurement logic of government-backed defense contractors rather than private-sector cybersecurity firms. Internal documents show that Knownsec does not restrict its infrastructure to domestic providers; instead, it strategically procures European hosting infrastructure, including services from companies such as EDIS and Impreza. These foreign VPS and storage nodes provide staging grounds for scanning operations, payload delivery, redirection infrastructure, and exfiltration endpoints. Their geographic dispersion reduces attribution risk and increases operational reach, aligning with the needs of state customers who require global coverage and plausible deniability.

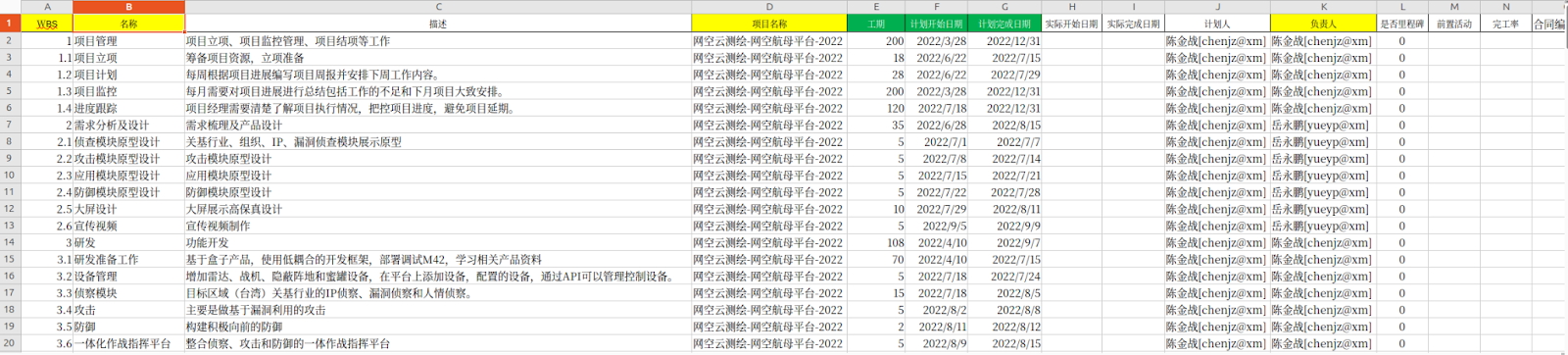

Financial organization within Knownsec also reflects a formalized, state-integrated structure. Leaked WBS project sheets reveal clearly defined cost centers, funding lines, and project sponsors, which are exactly the type of internal accounting frameworks used in China’s defense-industrial enterprises. Dedicated budgets exist for offensive R&D, data acquisition, infrastructure hosting, and specialized tools like GhostX and Passive Radar as seen in the excel images from the dump. This financial governance ensures continuity across long-term development cycles and indicates that Knownsec’s offensive tooling is not an ad-hoc initiative but an institutionalized capability sustained by predictable funding streams.

A crucial component of the supply chain is the data acquisition ecosystem. Knownsec’s massive o_data_* archives encompassing foreign breach dumps, credential collections, telecom subscriber databases, and national-ID repositories come from a mix of purchases, criminal-market harvesting, and internal scraping operations. These datasets form the human-intelligence substrate upon which exploitation and social-engineering operations depend. Similarly, Knownsec’s PCAP supply chain relies on compromised machines, operator-controlled servers, or cooperation from state entities to provide raw network captures that feed Passive Radar’s analytical engine. The success of ZoomEye likewise depends on a distributed scanning infrastructure, sustained by supporting nodes, bandwidth, and hardware that Knownsec maintains across multiple jurisdictions.

Taken together, these elements show that Knownsec’s supply chain is not incidental; it is deliberately constructed to serve national offensive cyber objectives. Its infrastructure procurement resembles the logistical patterns of government-funded cyber units; its data ingestion relies on pipelines typical of intelligence services; and its budgeting and work breakdown structures parallel those of state research contractors. Whether through hosting arrangements abroad, civilian data lakes turned into intelligence assets, or long-term PCAP sourcing, Knownsec’s dependencies align closely with Chinese government procurement cycles and strategic priorities, underscoring its role as an embedded component of the PRC’s broader cyber operations ecosystem.

Evidence from internal documents shows:

- They maintain internal cost centers for offensive tooling.

- WBS projects show formal funding lines with project sponsors.

- External datasets are purchased or harvested from criminal markets.

- Infrastructure procurement mirrors government-funded contractor operations.

Dependencies

- PCAP supply chain (victim or operator-controlled hosts)

- ZoomEye sensor infrastructure

- Data lake ingestion pipelines

- Chinese-government procurement cycles

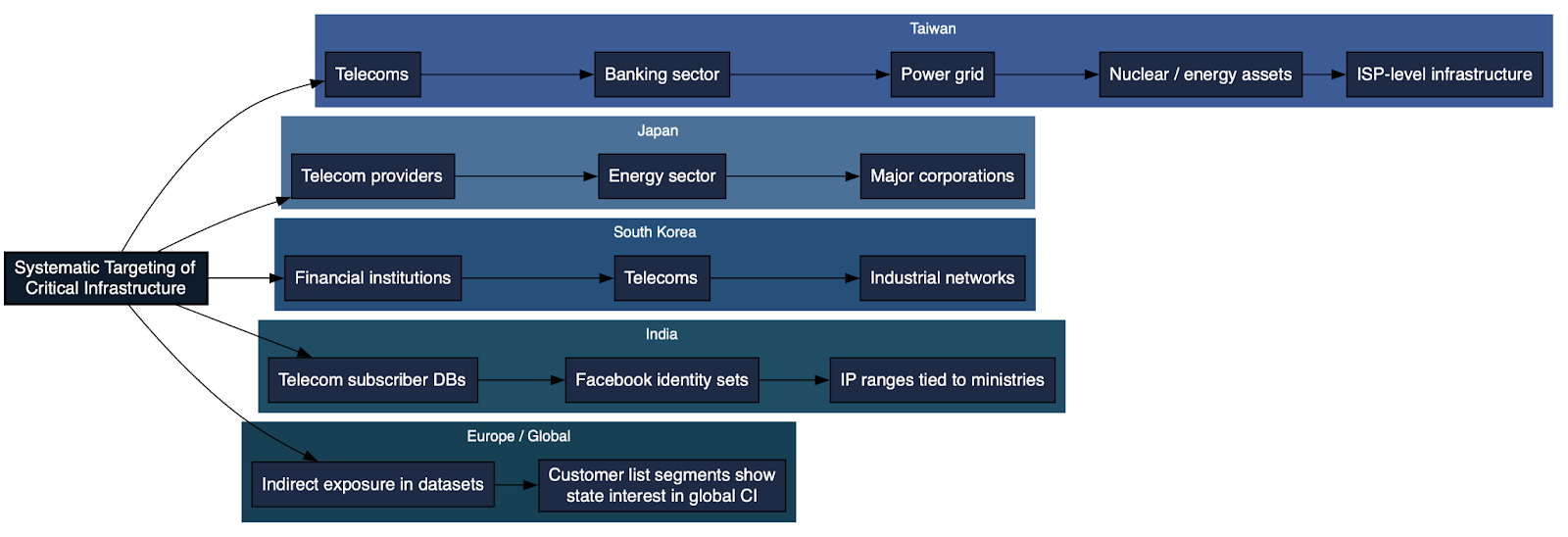

GLOBAL TARGETING

Knownsec’s leaked infrastructure data reveals a clear pattern of structured, high-value targeting focused on the critical infrastructure of strategically significant nations. Even in the limited-resolution tables available, the indicators of compromise (IOCs) point to a deliberate and methodical mapping of Taiwan’s financial, telecommunications, and energy sectors. The sample extracted entries illustrate this well: exposed Fortinet firewalls at Nan Shan Life Insurance and Hua Nan Commercial Bank, publicly reachable Sophos XG appliances at Chunghwa Telecom, and a vulnerable Check Point service tied to Taipower, Taiwan’s national energy provider. These enumerated services tagged by IP, port, device type, and application banner function as prevalidated targets, ready for exploitation by GhostX, network-fingerprinting modules, or customized military tooling. Although these samples represent only a fraction of the full dataset, they demonstrate the precision with which Knownsec cataloged foreign infrastructure exposure.

When these IOCs are contextualized within the broader leak, a picture of systematic targeting emerges. Taiwan is disproportionately represented across the leak, with evidence of interest not only in major telecom operators and financial institutions but also in power grid, nuclear-energy, and ISP-level assets. This coverage aligns closely with PRC strategic priorities and suggests an intent to build comprehensive operational knowledge of Taiwan’s connectivity fabric, resilience posture, and critical dependencies. Similar patterns appear in Knownsec’s datasets for Japan, where telecom providers, energy-sector nodes, and major industrial corporations are cataloged; and in South Korea, where financial institutions, telecom networks, and industrial infrastructure feature prominently.

Beyond East Asia, the targeting footprint widens. Knownsec’s o_data_* records include Indian telecom subscriber databases, Facebook identity datasets, and infrastructure ranges associated with Indian ministries. This mirrors Beijing’s intelligence interest in India’s digital ecosystem and supports operations requiring identity correlation or demographic profiling. Meanwhile, portions of the dataset referencing European or Western entities appear more fragmented, but they nonetheless indicate indirect exposure: customer lists and sector-tagged entries suggest an intelligence appetite for global critical infrastructure and multinational corporations, even if not yet operationalized at the same scale as East Asia.

Taken together, these patterns show that Knownsec’s targeting is strategic, multi-regional, and overtly political, aligning with the geopolitical interests of the PRC. The infrastructure data is not random reconnaissance; it is a curated map of cyber terrain that would enable espionage, influence, and potentially pre-positioning for disruptive operations. Each IOC and sector-tagged asset represents not just a point of exposure but a node in an intelligence-gathering architecture designed to give Chinese state clients deep visibility into the operational backbone of foreign nations.

This represents strategic, multi-region, politically aligned targeting.

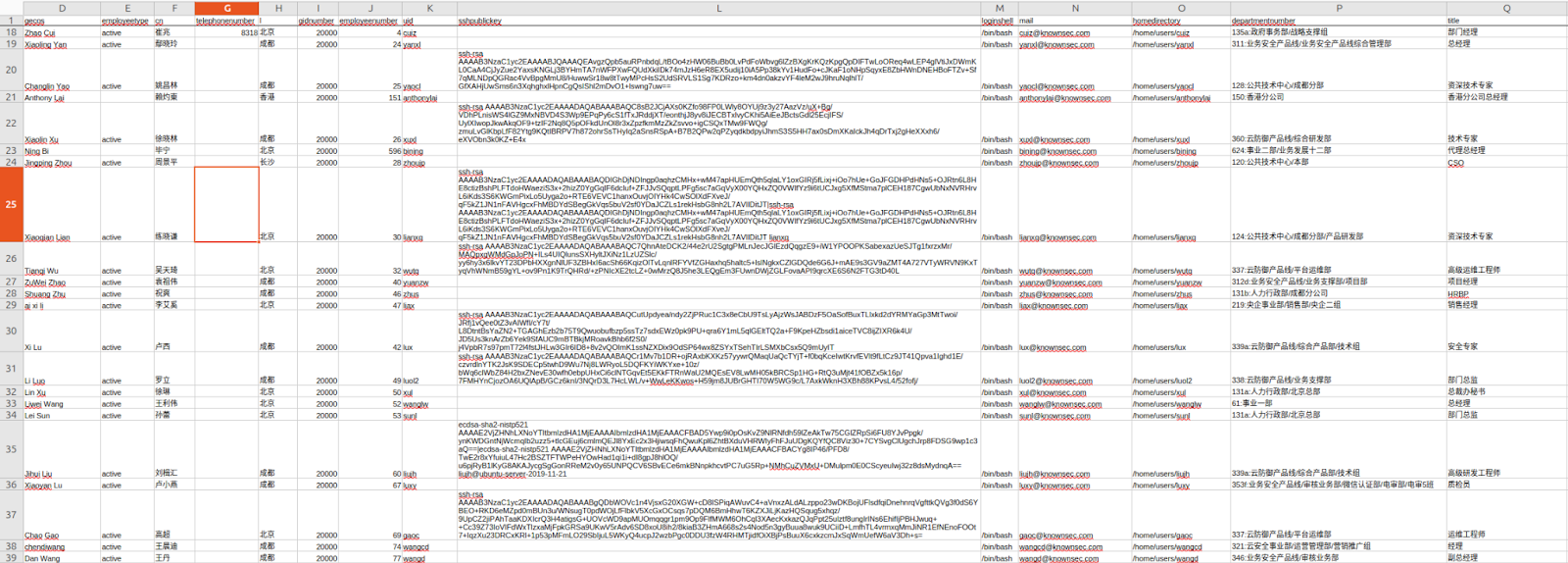

Internal Data Exposure: Email Addresses, Employee Identities, and Functional Roles

The Knownsec leak provides an unusually clear view into the human architecture of a Chinese cyber-contractor supporting national security, public-security bureaus, telecom regulators, and critical-infrastructure stakeholders. Unlike previous contractor leaks such as i-SOON (Anxun) which focused primarily on tools and client lists, the KnownSec corpus reveals a segment of internal personnel structures, spanning project owners, planners, cost-center sponsors, WBS task leads, and supporting engineers.

This internal data forms a blueprint of how Knownsec organizes and distributes responsibility across its offensive research, cyberspace-mapping, radar-engineering, and data-fusion programs. It offers a rare look at the people behind these capabilities, and exposes the specific functional chains by which projects move from concept to FOC (full operational capability).

Employee Identity Data

The leak contains a complete cross-section of Knownsec personnel across multiple divisions:

- 404 Security Lab (exploit research, offensive engineering, pentesting)

- Product Technology R&D Center (platform R&D, cyberspace mapping)

- Product Technology Department (hardware radar, UI/UX, testing)

- Product Technology Center 141 (high-level technical governance)

- Public-Security Research Institute (entity fusion, PSB analytic systems)

A total of 22 named employees appear in the materials, each tied to specific organizational units and assigned responsibilities inside multi-stage research or engineering efforts. These employees represent a spectrum of roles from senior leadership with strategic authority to WBS task owners responsible for tactical implementation details.

This personnel visibility is valuable for understanding:

- Internal tasking mechanisms

- Operational structure beneath Knownsec’s capabilities

- Which individuals enable offensive, defensive, or fusion-support tasks

- How work is distributed across government-sponsored projects

Where relevant, email addresses and internal accounts allow correlation with procurement records, code repositories, or external infrastructure should those indicators surface elsewhere.

Internal Email Address Patterns

Every email address in the dump uses one of two company formats:

- @knownsec.com → Headquarters operational accounts

- @xm.knownsec.com → Xiamen-based R&D and engineering offices

No personal external addresses appear for employees; only official Knownsec accounts are used inside project governance systems.

The following email addresses were recovered from the leak so far:

- zouxy2@knownsec.com

- suig@knownsec.com

- mas@knownsec.com

- wangcp2@knownsec.com

- chenc6@knownsec.com

- hey5@knownsec.com

- raosh@knownsec.com

- anyh@knownsec.com

- liuj13@knownsec.com

- xuc2@knownsec.com

- niexy2@knownsec.com

- chenrl@xm.knownsec.com

- chenjz@xm.knownsec.com

- wangll@xm.knownsec.com

- chenh4@xm.knownsec.com

- liwc@xm.knownsec.com

- wangl8@xm.knownsec.com

- yangwh2@knownsec.com

- zhanghj@knownsec.com

These addresses correspond directly to organizational positions inside Knownsec’s secure research and engineering divisions. There are no “throwaway” or operational aliases (e.g., Gmail/QQ/ProtonMail), which underscores that these individuals are internal employees, not contractors or external operators.

Functional Role Taxonomy

The personnel records reveal a clear hierarchy divided into strategic, operational, technical, and support layers.

Strategic Layer

These individuals control cost centers, approve research direction, and supervise multi-year programs. They connect Knownsec’s products to state-level requirements.

Key personnel:

- 李伟辰 (Li Weichen) – Head of Product Technology Center 141

These roles align with PRC state-integration patterns, where strategic decision-makers balance customer obligations with core R&D investment.

Operational Layer

Project managers, planners, and supervisors who translate strategic objectives into executable WBS chains.

Examples:

- PM and supervisor for 404 Security Research 2023

- PM/Planner for AW Detection (Project 391)

- PM/Planner for Hardware Radar 2022 V3

- PM of 404 Lab Pentest Research

- Project planners for Cyberspace Mapping (Carrier Platform)

These individuals operationalize multi-team engineering efforts, reflecting the governance model observed in defense integrators.

Technical Layer

Engineers responsible for exploitation, radar algorithms, system optimization, and data fusion.

Representative technical staff:

- WBS task owner for AW exploit and discovery chain

- Owner of AW 3.5 system testing

- Radar v3 implementation

- Radar optimization and stability

- Asset-identification system optimization

- User and functional testing tasks

- Data-fusion task execution for PSB

- Lead engineer for network-entity fusion research

This tier performs the core offensive and analytic development that Knownsec markets to PRC state customers.

Support Layer

Personnel performing QA, compliance, test engineering, and administrative approvals.

Notable roles:

- Beijing Testing Group (unnamed individuals except task owners)

- Default approver across R&D workflows

These roles ensure Knownsec’s platforms (Radar, Carrier Platform, offensive tooling) meet regulator and PSB deployment conditions.

Organizational Insight Derived from Internal Personnel Records

The internal data paints a clear picture of Knownsec as a multi-division cyber contractor seamlessly embedded within the broader security and intelligence ecosystem of the People’s Republic of China. Its organizational structure, personnel assignments, and project governance models demonstrate a company that is not merely providing commercial cybersecurity services but is directly supporting national cybersecurity mandates, public-security operations, and critical-infrastructure oversight. Every major division within Knownsec aligns with a corresponding state need, creating an operational architecture that mirrors the functions of a state-affiliated defense integrator.

This alignment is particularly visible in how technical departments map to specific government tasking. The 404 Lab serves as the offensive research and exploit-development hub, producing capabilities that directly support public-security bureaus and the national CERT apparatus. Meanwhile, the Product Technology Centers operate as the engineering backbone for large-scale cyberspace-mapping platforms used by telecom regulators such as Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) and Critical Infrastructure Intelligence Center (CNNIC). Parallel to these, the Public-Security Research Institute builds data-fusion and analytic systems tailored for police units, reflecting a tight coupling between Knownsec’s internal R&D efforts and the investigative workflows of law-enforcement agencies.

Even the company’s internal email domains reinforce these functional distinctions. Accounts using @xm.knownsec.com cluster around engineering-heavy roles located in Xiamen, supporting platform development, radar systems, and systems integration. In contrast, @knownsec.com addresses are associated with research, data-fusion, offensive tooling oversight, and leadership responsibilities in Beijing. These boundaries reveal an internal trust and specialization model consistent with sensitive state-oriented development work.

Knownsec’s work-breakdown-structure (WBS) governance further shows a degree of engineering discipline typically found in military-industrial contractors. Projects are organized under formal sponsorship, with named approvers, supervisory layers, and sequenced deliverables. Every task has a clearly identified owner, and responsibilities cascade through planners, supervisors, and technical implementers. This hierarchy captures operational accountability at each stage, ensuring that sensitive tooling and large-scale platforms move through development in a controlled, auditable way.

Personnel mapping highlights how deeply the company depends on specialized, interoperable technical units. Offensive engineers in the 404 Lab, radar architects in the Product Technology Department, large-scale mapping engineers in the R&D Center, and data-fusion specialists in the Public-Security Research Institute all operate in defined silos. However, these silos are not isolated; they form a layered production pipeline that transforms exploit research into operational platforms capable of national-scale reconnaissance, targeting, and surveillance. In this way, Knownsec operates not just as a security vendor but as a critical node in China’s state-aligned cyber ecosystem, where human expertise, organizational structure, and strategic intent converge into a cohesive operational capability.

Key observations:

- Departments align to state tasking

- 404 Lab produces exploit and offensive research for PSB and national CERT.

- Product Tech Centers deliver cyberspace-mapping platforms for telecom regulators (MIIT, CNNIC).

- Public-Security Research Institute builds fusion systems directly for police units.

- Email domains reinforce internal trust boundaries

- @xm.knownsec.com maps to engineering-heavy functions.

- @knownsec.com maps to research, fusion, and leadership roles.

- WBS governance reveals engineering maturity

- Workflows mirror military-industrial contractors with formal sponsorship, deliverable tracking, and internal approvals.

- Each task has a named owner, capturing chains of operational accountability.

- Personnel mapping exposes internal specialization

- Offensive engineering, radar systems, cyberspace mapping, and data fusion are isolated but interoperable teams.

- These silos reflect a layered pipeline that moves from exploit research to national-scale targeting platforms.

Strategic Significance of the Internal Data Exposure

The personnel information exposed in the Knownsec leak provides an unusually rich foundation for adversarial intelligence analysis. Instead of viewing Knownsec through the limited lens of tools, platforms, or public-facing capabilities, analysts can now reconstruct the company’s true operational architecture by tracing projects, responsibilities, and decision-making authority back to named individuals. This transforms Knownsec from an abstract corporate entity into a map of people, teams, and functions revealing how its internal machinery supports the broader PRC cyber apparatus.

With individual identities tied directly to work-breakdown structures, cost centers, and project leadership roles, analysts can identify exactly who drives offensive research and development. Names connected to GhostX, Radar 2022V3, the Cyberspace Mapping “Carrier Platform,” and data-fusion systems allow a clear understanding of which personnel shape the direction of core offensive and reconnaissance tools. Decision-making chains also emerge: who authors budget proposals, who approves them, who signs off on deliverables, and who assumes technical ownership of the most sensitive tasks. These insights expose how Knownsec manages risk, allocates resources, and governs the development of capabilities that ultimately serve national-level customers.

The data also closes the loop between Knownsec’s internal operations and China’s public-sector clients. Analysts can now link specific individuals to the ministries, state-owned enterprises, and provincial public-security bureaus they support. Whether developing mapping infrastructure for MIIT, vulnerability research for PSB, or reconnaissance tooling for State Grid or the national telecom operators, the personnel lists clarify which engineers and managers are responsible for executing state-directed work. This creates a direct, traceable line from human operators to cyber capabilities used by the PRC government.

Granular operator-level visibility of this kind is almost never present in Chinese contractor leaks. Typical disclosures provide tools, artifacts, or billing records, but rarely full mappings of engineers, planners, cost-center owners, and project supervisors. The Knownsec leak stands apart in that it reveals not only what the company builds, but who builds it, who authorizes it, and who ensures its integration into the state security ecosystem. For analysts, this level of detail offers an unprecedented window into the human and organizational architecture of one of China’s most capable cyber contractors.

State Security and Intelligence Organizations Identified in the Knownsec Leak

The Knownsec leak provides direct insight into the company’s relationship with the national security, cyber-regulation, and public-security ecosystems of the People’s Republic of China. The documents show that Knownsec does not operate as a conventional cybersecurity vendor but instead as a tightly integrated contractor supporting multiple layers of the PRC’s intelligence and public-security infrastructure. The presence of specific ministries, bureaus, CERT bodies, and state-owned enterprises across internal worksheets and customer tables reveals a contractor ecosystem that mirrors the organizational structure of the Chinese cyber state.

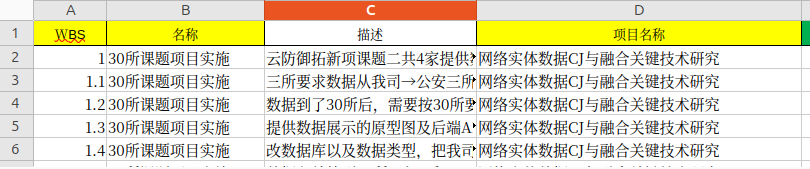

The Ministry of Public Security (MPS) emerges as the most prominent stakeholder in Knownsec’s operations. Multiple internal project sheets reference public-security intelligence requirements, entity-fusion deliverables, and policing-oriented research, suggesting that Knownsec’s tools such as Network Entity Data C fusion systems and analytics platforms feed directly into law-enforcement intelligence workflows. The inclusion of the Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau as a direct customer reinforces that Knownsec supports both national and regional PSB units, providing technical capabilities that underpin investigatory, surveillance, and cyber-intelligence missions. The company’s Public-Security Research Institute acts as an intermediary, developing analytic systems specifically designed for MPS use, including the “30 Institutes” project, which historically links to police intelligence research centers.

Beyond policing, the documents show that Knownsec’s platform technologies align with the needs of China’s cyber governance infrastructure. The MIIT and CNNIC, which oversee network resources, DNS infrastructure, and telecom regulation, appear in customer lists. These associations suggest that Knownsec’s large-scale cyberspace-mapping platforms and radar systems contribute to regulatory visibility across the national network space. Similarly, the presence of CNCERT/CC and CCERT indicates that Knownsec plays a role in the country’s coordinated incident response and vulnerability-management programs. These organizations sit at the intersection of defensive coordination and intelligence-informed cyber situational awareness, and Knownsec’s products appear to support both domains.

Several state-owned enterprises also appear in the dataset, including State Grid, China Mobile, and China Telecom. While not intelligence agencies in name, these entities represent critical-infrastructure and telecommunications networks of high strategic value to Chinese state security. Their appearance in Knownsec’s internal documentation implies that Knownsec provides reconnaissance, mapping, or defensive monitoring capabilities that directly support national requirements for energy grid protection, telecom oversight, and large-scale network exposure assessment. These relationships blur the line between commercial engagement and state-aligned intelligence support, reflecting the dual-use nature of Knownsec’s core platforms.

Taken together, the organizations referenced in the leak form a coherent picture of how Knownsec embeds itself in the state’s cyber and intelligence apparatus. The company’s divisions and product lines align closely with the functional needs of public-security bureaus, national regulators, telecom carriers, and critical infrastructure operators. The network of relationships visible across the documents illustrates a contractor deeply woven into China’s national security architecture. It confirms that Knownsec’s internal operations, research programs, and platform developments are not random or commercially opportunistic but are systematically shaped by the requirements of the PRC’s intelligence and regulatory ecosystem.

Summary: Intelligence / Security Org List

OrganizationTypeRole in DumpMPS – Ministry of Public SecurityNational Police / IntelligencePrimary stakeholder for offensive, data-fusion, and entity analytics systemsBeijing Public Security BureauMunicipal PSBDirect consumer of Knownsec platforms and analysisPublic-Security Research Institute (internal Knownsec)PSB-aligned R&DBuilds fusion tech for PSB intelligence unitsMIITTelecom & Cyber RegulatorOversight for mapping platforms, radar outputsCNNICNational DNS AuthorityDomain-level surveillance & infrastructure mappingCNCERT/CCNational CERTNational-level vulnerability, incident intelCCERTEducation & Research CERTSupporting CERT node“30 Institutes” (PSB Research Institutes)Public-Security Intelligence R&DEntity fusion, data pipelines, analytic systemsState GridStrategic CII targetIncluded for reconnaissance and mappingChina Mobile / China TelecomTelecom carriersInfrastructure mapping and metadata pipelines

APPENDICES

Appendix A Combined IOC List (Knownsec Leak Corpus)

Indicator of Compromise Summary Knownsec TargetDB, Radar, and Foreign CI Mapping

Below is the unified IOC dataset extracted from all Knownsec screenshots, TargetDB tables, Radar 2022V3 outputs, and CI-targeting images provided in this project.

High-Confidence IP-Level IOCs (Critical Infrastructure Targets)

(All derived from Knownsec’s internal TargetDB screenshots for Taiwan CII)

country,organization,ip,port,service,device_type,notes

Taiwan,Nan Shan Life Insurance,210.242.194.198,443,httpd,Fortinet FortiGate,Listed as critical asset in CII table

Taiwan,Nan Shan Life Insurance,210.242.194.198,80,httpd,Fortinet FortiGate,Same host over HTTP

Taiwan,Hua Nan Commercial Bank,219.80.43.14,443,httpd,Fortinet FortiGate,Banking-sector firewall target

Taiwan,Hua Nan Commercial Bank,219.80.43.14,80,httpd,Fortinet FortiGate,Appears twice in Knownsec radar slices

Taiwan,Chunghwa Telecom,220.130.186.202,10443,httpd,Sophos XG,Telecom-edge gateway in CII targeting

Taiwan,Chunghwa Telecom,220.130.186.203,10443,httpd,Sophos XG,Sister device to above; separate PoP

Taiwan,Bank of Taiwan,103.21.60.3,8080,httpd,Fortinet FortiGate,Core financial gateway

Taiwan,Taipower,61.65.236.240,18264,httpd,Check Point SVN,Energy-sector firewall; high-value infrastructure

Medium-Confidence IOCs (Region-Expansion & Mapping Targets)

From Knownsec’s internal WBS expansion directives (WBS 7 & 8):

region,ip_range,notes

United States,100000_new_ips,Expansion directive: increase target coverage by 100k IPs

Taiwan,10000_new_ips,Expansion directive: +10k key Taiwan IP segments

YN_region,expansion_flag,New coverage region in platform WBS

MD_region,expansion_flag,New coverage region in platform WBS

WL_region,expansion_flag,New coverage region in platform WBS

ELS_region,expansion_flag,New coverage region in platform WBS

Data-Lake / Credential-Dump Indicators

From the o_data datasets referenced in the Knownsec HDFS export list:

dataset_name,country_or_sector,notes

o_data_taiwanahooemailpwd_tw,Taiwan,Credentials (Yahoo TW email/password dump)

linkedin_brazil,Brazil,LinkedIn identity dataset

linkedin_southafrica_202305,South Africa,LinkedIn identity dataset

o_data_facebookuserinfo_in,India,Facebook identity dump

o_data_telecom_info_india,India,Telecom subscriber dataset

o_data_royalenfield_india,India,Automotive customer dataset

o_data_shopping_order_vietnam,Vietnam,E-commerce customer dataset

o_data_shopping_vip_vietnam,Vietnam,VIP commerce dataset

o_data_insuranceindia_data,India,Insurance records dataset

o_data_sms_active_ru,Russia,SMS/telecom activity dataset

o_data_telderi_ru,Russia,Marketplace dataset

o_data_skolkovo,Russia,Skolkovo-related dataset

o_data_github,Global,GitHub developer dataset for targeting correlation

o_data_telegram_user_info,Global/Regional,Telegram identity dataset

o_data_instagram_temp,Global/Regional,Instagram scraped temp dataset

Organizational Targets & Associates (Based on Internal “典型客户” / TargetDB Sector Lists)

The following organizations appear repeatedly in Knownsec’s internal customer lists, procurement docs, or radar/TargetDB slices. These constitute strategic targeting and cooperation indicators even when no IP/IaaS attributes were provided.

country,organization,type,notes

China,Ministry of Public Security,State Client,Internal security customer consuming Knownsec platforms

China,People’s Bank of China,Financial Regulator,Monitored via PKI-linked infrastructure

China,CFCA (Financial Certification Authority),Financial PKI Infrastructure,High-value crypto/identity target

China,State Grid Corporation of China,Critical Infrastructure,Energy/SCADA mapping

China Mobile,Telecom,Carrier mapping and radar integration

China Telecom,Telecom,Carrier mapping and radar integration

China Education & Research CERT (CCERT),Academic CERT,Emergency-response alignment

China,State Council Procurement Network,Government ops,Procurement and surveillance-aligned workload

China,Beijing Public Security Bureau,Policing/LEO,Multiple contract purchases in ledger

Taiwan,Bank of Taiwan,Financial institution,Direct firewall mapping (See A.1)

Taiwan,Hua Nan Commercial Bank,Financial institution,Direct firewall mapping (See A.1)

Taiwan,Nan Shan Life Insurance,Insurance/Financial,Direct firewall mapping (See A.1)

Taiwan,Chunghwa Telecom,Telecom,Edge infrastructure fingerprinted (See A.1)

Taiwan,Taipower,Energy/Nuclear,Check Point SVN asset identified

India,Telecom Companies,Telecom,Featured in o_data_telecomcompanies_in

India,Ministry-adjacent IP ranges,Government,Identified in mapping directives

Vietnam,Shopping-order and VIP datasets,E-commerce / social profiling,Used for persona correlation

Russia,Skolkovo / Telderi / SMS datasets,Industrial / Social,Used for identity correlation

Global,GitHub developer data,Developer ecosystem,Used for deanonymization & target pivoting

Tooling-Linked IOC Classes (High-Level Indicators)

Where specific domains/servers were not provided, Knownsec tooling reveals classes of IOCs that defenders should track.

category,indicator_type,example,notes

GhostX,Persistence IOCs,admin account creation on routers,Indicates long-term foothold

GhostX,Network Manipulation,DNS hijack configurations,Used for redirect/exfil

Un-Mail,Webmail compromise,XSS injection points on webmail portals,High-risk COMINT vector

Passive Radar,Internal reconnaissance,PCAP ingestion servers,Victim-owned or attacker-controlled

Carrier Platform,Recon infrastructure,ZoomEye-linked scanners,High-volume scanning nodes

Radar 2022V3,Protocol-fingerprinting output,service banners/flows,Used to classify assets for later exploitation

Data-Fusion Projects,Identity correlation,IAM/credential merges,Used by Public-Security clients

These are behavioral indicators, not atomic IOCs, but they are directly tied to Knownsec’s operational tooling.

Appendix B MITRE ATT&CK Map

Appendix C Organizational Schema (Text)

State Ministries

↓

Knownsec Executive Leadership

↓

404 Lab | Product R&D | Military Division | Data Division

↓

Project Managers → Engineers → Operators

↓

Toolchain Deployment

Appendix D Master File List from Dump

Here is a consolidated file list of all Knownsec-related uploads in this project, reconstructed from the conversation history, OCR references, system logs, and tool notes.

This includes images, PDFs, spreadsheets, and indexes you uploaded for the Knownsec leak analysis.

MASTER FILE LIST OF UPLOADED FILES (Knownsec Project)

PDFs (Leak Documents & Articles)

Leak Documentation

- 关基目标库说明文档_V202309.pdf (multiple screenshots provided)

- 无源雷达–产品文档 (Passive Radar Product Manual) (screenshots extracted)

- *404安全研究2023 – internal sheets (as images, WBS pages)

- 网空云测绘-网空航母平台-2022 (Carrier Platform 2022 WBS sheets)

- 硬件雷达2022V3.0.0.0 主力项目 (Radar Project 2022V3 WBS)

- 网络实体数据C与融合关键技术研究 (PSRI / “30 Institutes” project sheets)

Spreadsheets & Data Index Files

1. Personnel / Department / Project Indexes

- master index departments and projects.xlsx

- master index emails and people.numbers

- Untitled.xlsx (additional personnel / dept mappings)

2. Internal Project/Deliverable Sheets

(Uploaded via screenshots but constitute distinct files)

- 404 Lab WBS summary sheets (≈ 10 images)

- 391 AW Detection Project sheets (≈ 10 images)

- Carrier Platform WBS sheets (Product Technology R&D) (≈ 10+ images)

- Radar 2022V3 WBS sheets (Product Tech Dept) (≈ 10+ images)

- Public-Security Research Institute fusion project sheets (≈ 10 images)

C. Image Files (Screenshots)

Knownsec Internal Documents (numbered 1–64)

1.png

3.png

4.png

5.png

6.png

7.png

8.png

9.png

10.png

11.png

12.png

13.png

14.png

15.png

16.png

17.png

18.png

19.png

20.png

23.png

24.png

25.png

26.png

28.png

29.png

30.png

31.png

32.png

33.png

34.png

35.png

36.png

37.png

38.png

39.png

40.png

41.png

42.png

43.png

44.png

45.png

46.png

47.png

48.png

49.png

50.png

51.png

52.png

53.png

54.png

55.png

56.png

57.png

58.png

59.png

60.png

61.png

62.png

63.png

64.png.

Reconstructed File Descriptions (1–64)

1–11: Public-Security Research Institute (PSRI) – “Network Entity Data C & Fusion Key Tech Research”

These files corresponded to the “30 Institutes” fusion project, showing:

- PSB-driven data-fusion research

- Entity correlation pipelines

- Multi-dataset integration workflows

- WBS tasking for Zhang Huijie and Yang Guihui

- Deliverables tied directly to Public Security Bureau (公安三所) requirements

Typical page contents:

12–20: 404 Security Research 2023 (404实验室) / AW Detection Project 391

These images included:

- 404 Lab internal research objectives

- Vulnerability mining tasks

- AW (Asset & Weakness) detection research

- Exploit-related WBS

- Roles for Ma Shuai, Wang Cuiping, Chen Cheng, He Yan

- Related pentest research flows

Typical mapping:

23–36: Product Technology R&D Center – Cyberspace Mapping Platform (“Carrier Platform 2022”)

These images belonged to the 网空航母平台-2022 project, showing:

- Region-coverage expansion goals

- US/Taiwan key IP-range mapping

- Platform WBS tasks

- System component diagrams

- Planning roles for Chen Ruili, Chen Jinzhan, Wang Lili, Chen Hai

- Cost-center oversight by Li Weichen

Representative:

37–45: Hardware Radar 2022 V3 (产品技术部)

These files came from the Radar 2022V3 core project, including:

- Subsystem optimization tasks

- Feature development (vuln PoC ingestion, configuration checking)

- UI/UX tasks

- User testing and functional testing

- Technical owner mappings for An Yaxuan, Liu Xun, Xu Chao, Nie Xinyu

Mapping:

46–54: TargetDB / Critical Infrastructure Target Library

These screens captured the 关基目标库 (Critical Infrastructure Target Library):

- Sector classifications (military, telecom, energy, finance)

- IP counts (378,942,040)

- Regional coverage (26 geographies)

- Domain and asset listings

- Example targets: Taiwan banks, power grid, telecoms

Representative:

55–64: Data Business Division – HDFS o_data Datasets

This batch corresponds to the o_data_* dataset listings you uploaded, including:

- Indian telecom subscriber DBs

- Vietnam shopping-order datasets

- Russia SMS/telecom datasets

- Taiwan Yahoo credential dumps

- LinkedIn Brazil / South Africa

- GitHub user dataset

- Telegram data sets

Miscellaneous Internal Dataset References (via screenshots)

Not files themselves, but documented inside uploads:

- o_data_royalenfield_india

- o_data_rusnod_ru

- o_data_school_test

- o_data_shopping_order_vietnam

- o_data_shopping_vip_vietnam

- o_data_skolkovo

- o_data_sms_active_ru

- o_data_taiwan_uhq

- o_data_taiwanahooemailpwd_tw

- o_data_telderi_ru

- o_data_telecom_info_india

- o_data_telecomcompanies_in

- o_data_telegram_data

- o_data_telegram_user_info

- o_data_facebookuserinfo_in

- o_data_github

- o_data_instagram_temp

- o_data_insuranceindia_data

- linkedin_brazil

- linkedin_southafrica_202305

These were extracted from HDFS paths visible in the screenshots.