Inside the Kimsuky Leak: How the “Kim” Dump Exposed North Korea’s Credential Theft Playbook

Contents:

Part I: Technical Analysis

Part II: Goals Analysis

Part III: Threat Intelligence Report

Executive Summary

A rare and revealing breach attributed to a North Korean-affiliated actor, known only as “Kim” as named by the hackers who dumped the data, has delivered a new insight into Kimsuky (APT43) tactics, techniques, and infrastructure. This actor’s operational profile showcases credential-focused intrusions targeting South Korean and Taiwanese networks, with a blending of Chinese-language tooling, infrastructure, and possible logistical support. The “Kim” dump, which includes bash histories, phishing domains, OCR workflows, compiled stagers, and rootkit evidence, reflects a hybrid operation situated between DPRK attribution and Chinese resource utilization.

This report is broken down into three parts:

- Technical Analysis of the dump materials

- Motivation and Goals of the APT actor (group)

- A CTI report compartment for analysts

While this leak only gives a partial idea of what the Kimusky/PRC activities have been, the material provides insight into the expansion of activities, nature of the actor(s), and goals they have in their penetration of the South Korean governmental systems that would benefit not only DPRK, but also PRC.

Without a doubt, there will be more coming out from this dump in the future, particularly if the burned assets have not been taken offline and access is still available, or if others have cloned those assets for further analysis. We may revisit this in the future if additional novel information comes to light.

Part I: Technical Analysis

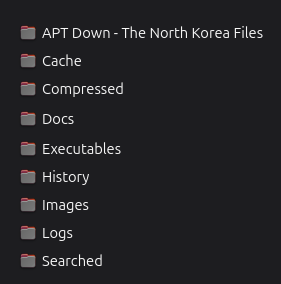

The Leak at a Glance

The leaked dataset attributed to the “Kim” operator offers a uniquely operational perspective into North Korean-aligned cyber operations. Among the contents were terminal history files revealing active malware development efforts using NASM (Netwide Assembler), a choice consistent with low-level shellcode engineering typically reserved for custom loaders and injection tools. These logs were not static forensic artifacts but active command-line histories showing iterative compilation and cleanup processes, suggesting a hands-on attacker directly involved in tool assembly.

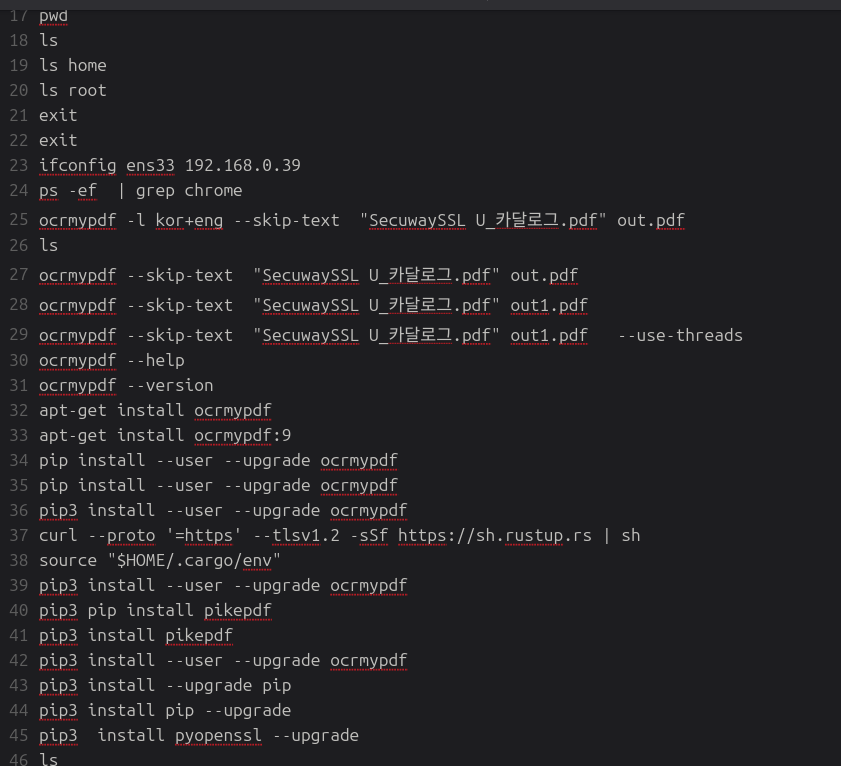

In parallel, the operator ran OCR (Optical Character Recognition) commands against sensitive Korean PDF documents related to public key infrastructure (PKI) standards and VPN deployments. These actions likely aimed to extract structured language or configurations for use in spoofing, credential forgery, or internal tool emulation.

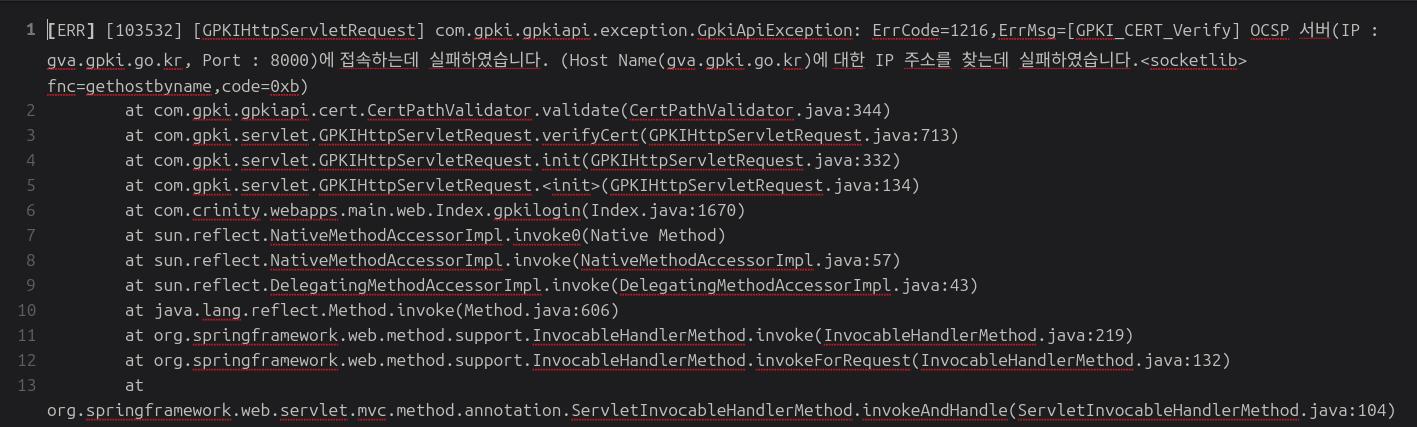

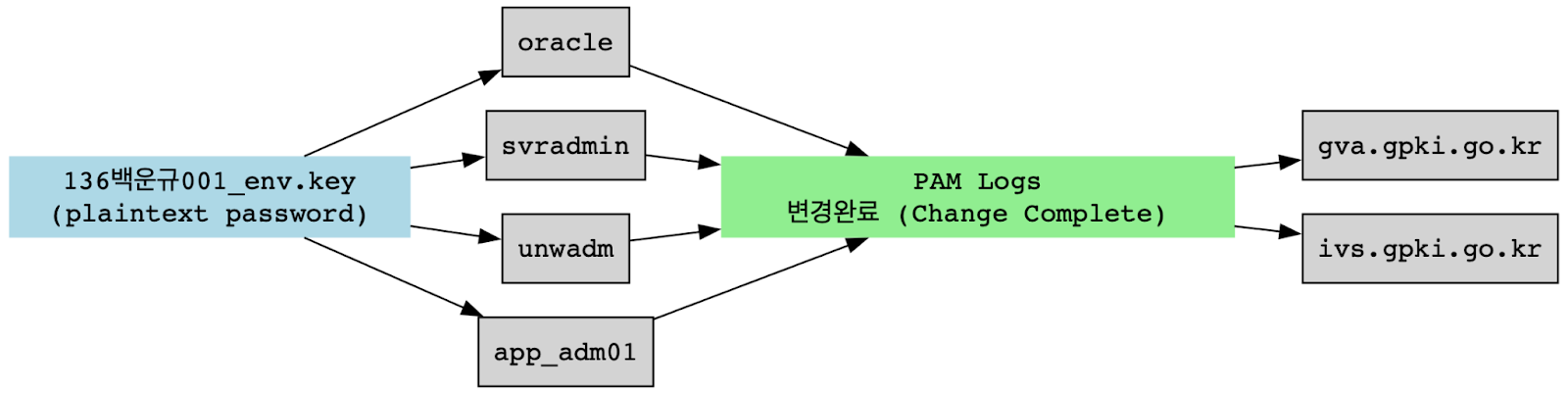

Privileged Access Management (PAM) logs also surfaced in the dump, detailing a timeline of password changes and administrative account use. Many were tagged with the Korean string 변경완료 (“change complete”), and the logs included repeated references to elevated accounts such as oracle, svradmin, and app_adm01, indicating sustained access to critical systems.

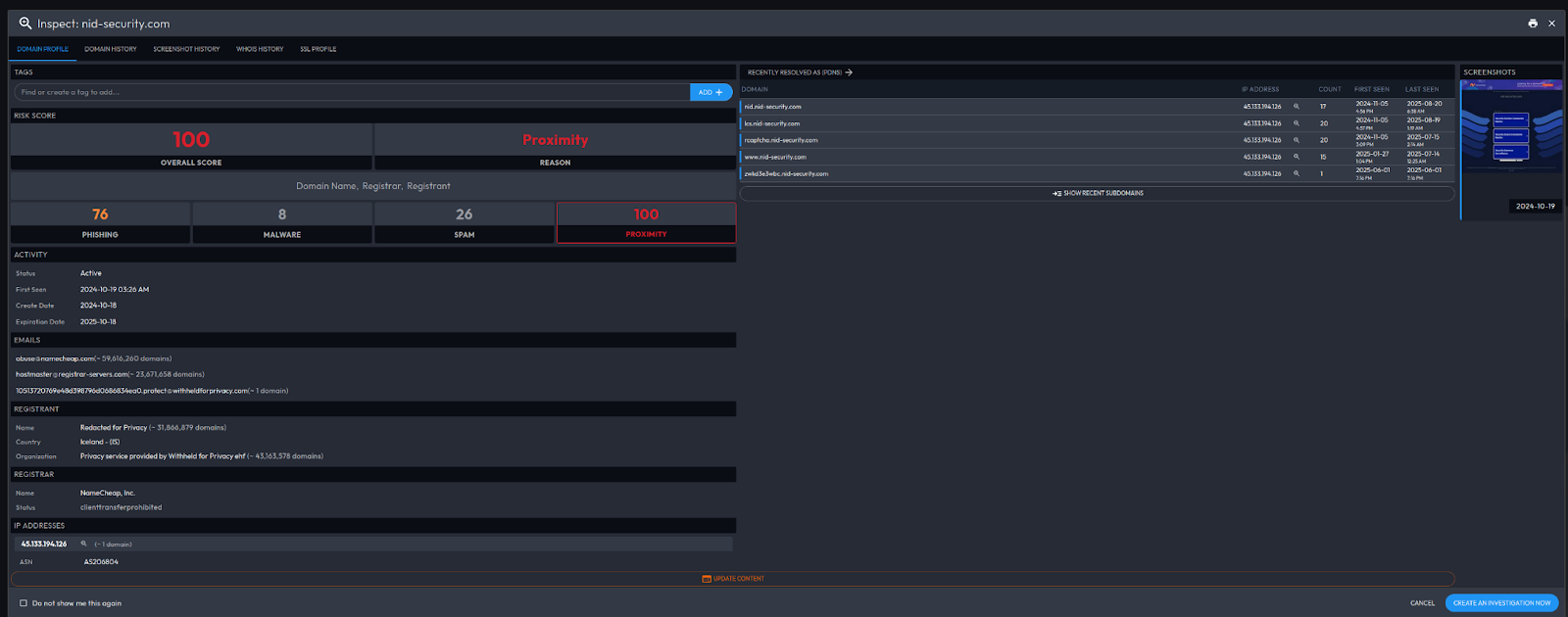

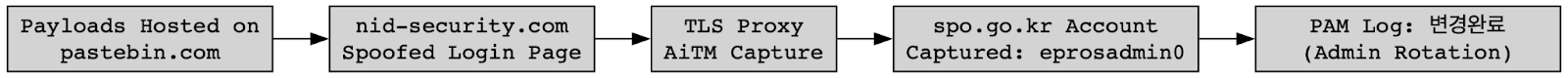

The phishing infrastructure was extensive. Domain telemetry pointed to a network of malicious sites designed to mimic legitimate Korean government portals. Sites like nid-security[.]com were crafted to fool users into handing over credentials via advanced AiTM (Adversary-in-the-Middle) techniques.

Finally, network artifacts within the dump showed targeted reconnaissance of Taiwanese government and academic institutions. Specific IP addresses and .tw domain access, along with attempts to crawl .git repositories, reveal a deliberate focus on high-value administrative and developer targets.

Perhaps most concerning was the inclusion of a Linux rootkit using syscall hooking (khook) and stealth persistence via directories like /usr/lib64/tracker-fs. This highlights a capability for deep system compromise and covert command-and-control operations, far beyond phishing and data theft.

Artifacts recovered from the dump include:

- Terminal history files demonstrating malware compilation using NASM

- OCR commands parsing Korean PDF documents related to PKI and VPN infrastructure

- PAM logs reflecting password changes and credential lifecycle events

- Phishing infrastructure mimicking Korean government sites

- IP addresses indicating reconnaissance of Taiwanese government and research institutions

- Linux rootkit code using syscall hooking and covert channel deployment

Credential Theft Focus

The dump strongly emphasizes credential harvesting as a central operational goal. Key files such as 136백운규001_env.key (The presence of 136백운규001_env.key is a smoking gun indicator of stolen South Korean Government PKI material, as its structure (numeric ID + Korean name + .key) aligns uniquely with SK GPKI issuance practices and provides clear evidence of compromised, identity-tied state cryptographic keys.) This was discovered alongside plaintext passwords, that indicate clear evidence of active compromise of South Korea’s GPKI (Government Public Key Infrastructure). Possession of such certificates would allow for highly effective identity spoofing across government systems.

PAM logs further confirmed this focus, showing a pattern of administrative account rotation and password resets, all timestamped and labeled with success indicators (변경완료: Change Complete). The accounts affected were not low-privilege; instead, usernames like oracle, svradmin, and app_adm01, often used by IT staff and infrastructure services, suggested access to core backend environments.

These findings point to a strategy centered on capturing and maintaining access to privileged credentials and digital certificates, effectively allowing the attacker to act as an insider within trusted systems.

- Leaked .key files (e.g., 136백운규001_env.key) with plaintext passwords confirm access to GPKI systems

- PAM logs show administrative password rotations tagged with 변경완료 (change complete)

- Admin-level accounts such as oracle, svradmin, and app_adm01 repeatedly appear in compromised logs

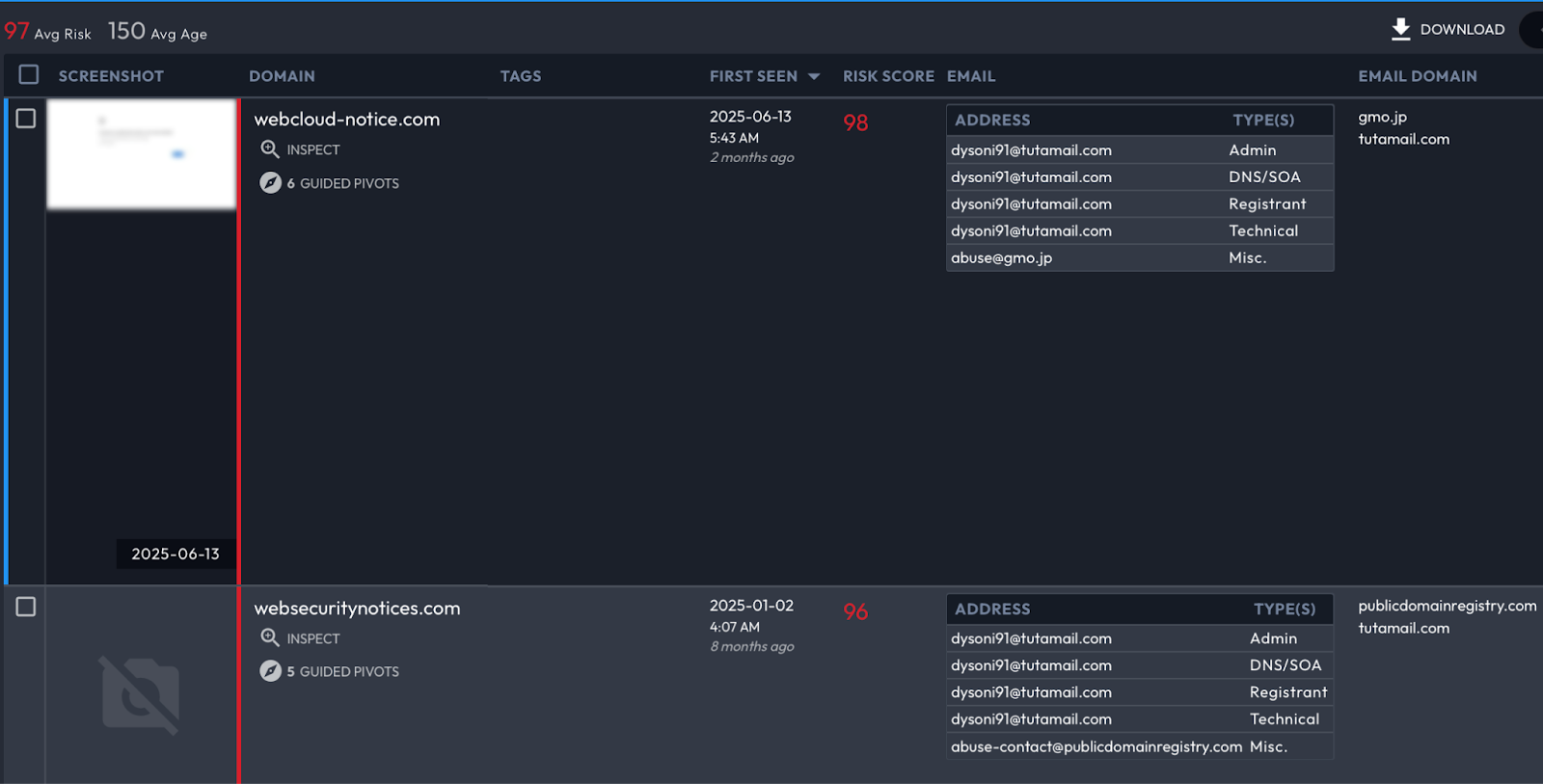

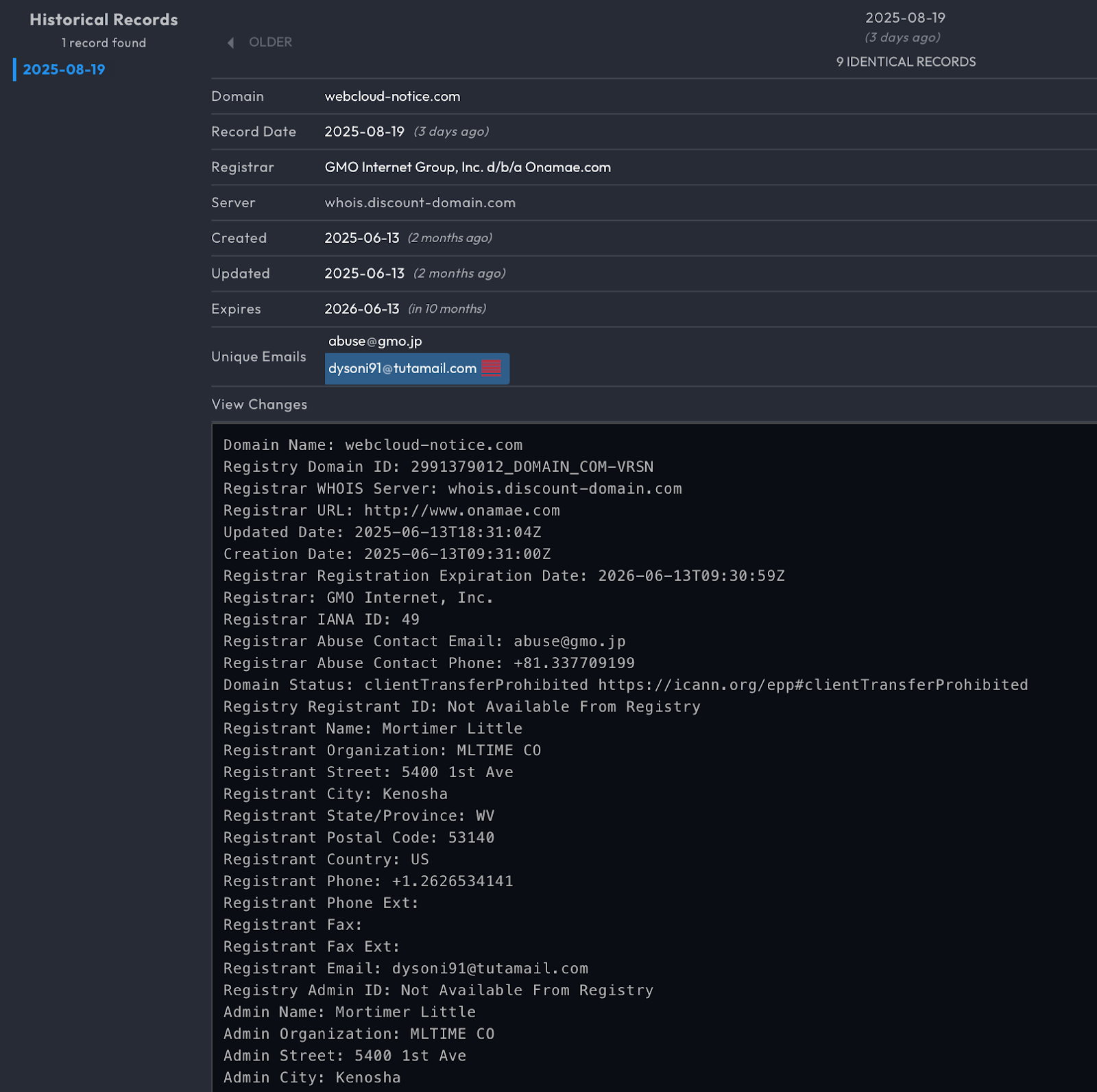

Phishing Infrastructure

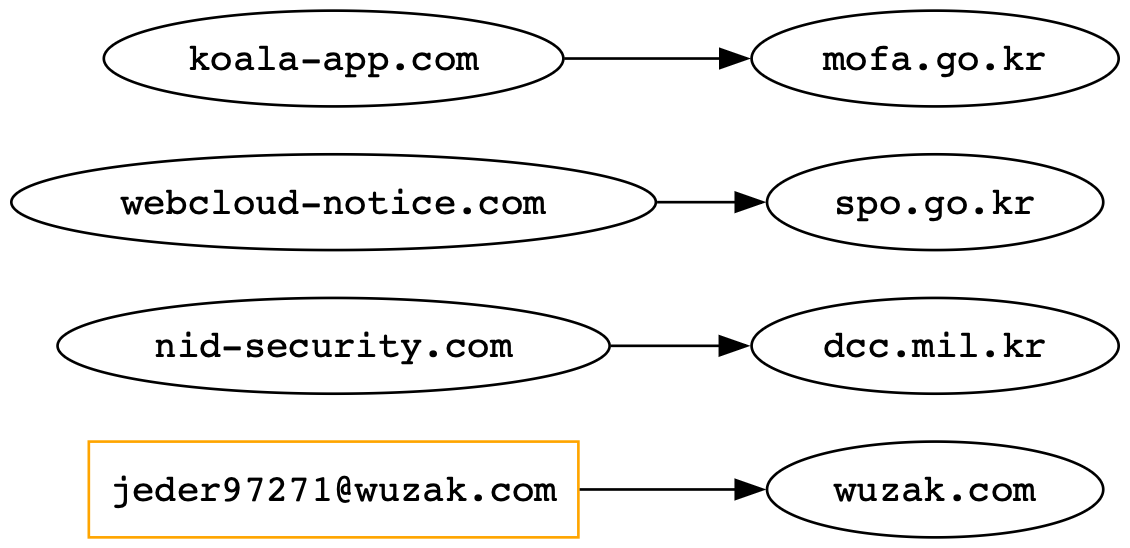

The operator’s phishing infrastructure was both expansive and regionally tailored. Domains such as nid-security[.]com and webcloud-notice[.]com mimicked Korean identity and document delivery services, likely designed to intercept user logins or deploy malicious payloads. More sophisticated spoofing was seen in sites that emulated official government agencies like dcc.mil[.]kr, spo.go[.]kr, and mofa.go[.]kr.

Burner email usage added another layer of operational tradecraft. The address jeder97271[@]wuzak[.]com is likely linked to phishing kits that operated through TLS proxies, capturing credentials in real time as victims interacted with spoofed login forms.

These tactics align with previously known Kimsuky behaviors but also demonstrate an evolution in technical implementation, particularly the use of AiTM interception rather than relying solely on credential-harvesting documents.

- Domains include: nid-security[.]com, html-load[.]com, webcloud-notice[.]com, koala-app[.]com, and wuzak[.]com

- Mimicked portals: dcc.mil[.]kr, spo.go[.]kr, mofa.go[.]kr

- Burner email evidence: jeder97271[@]wuzak[.]com

- Phishing kits leveraged TLS proxies for AiTM credential capture

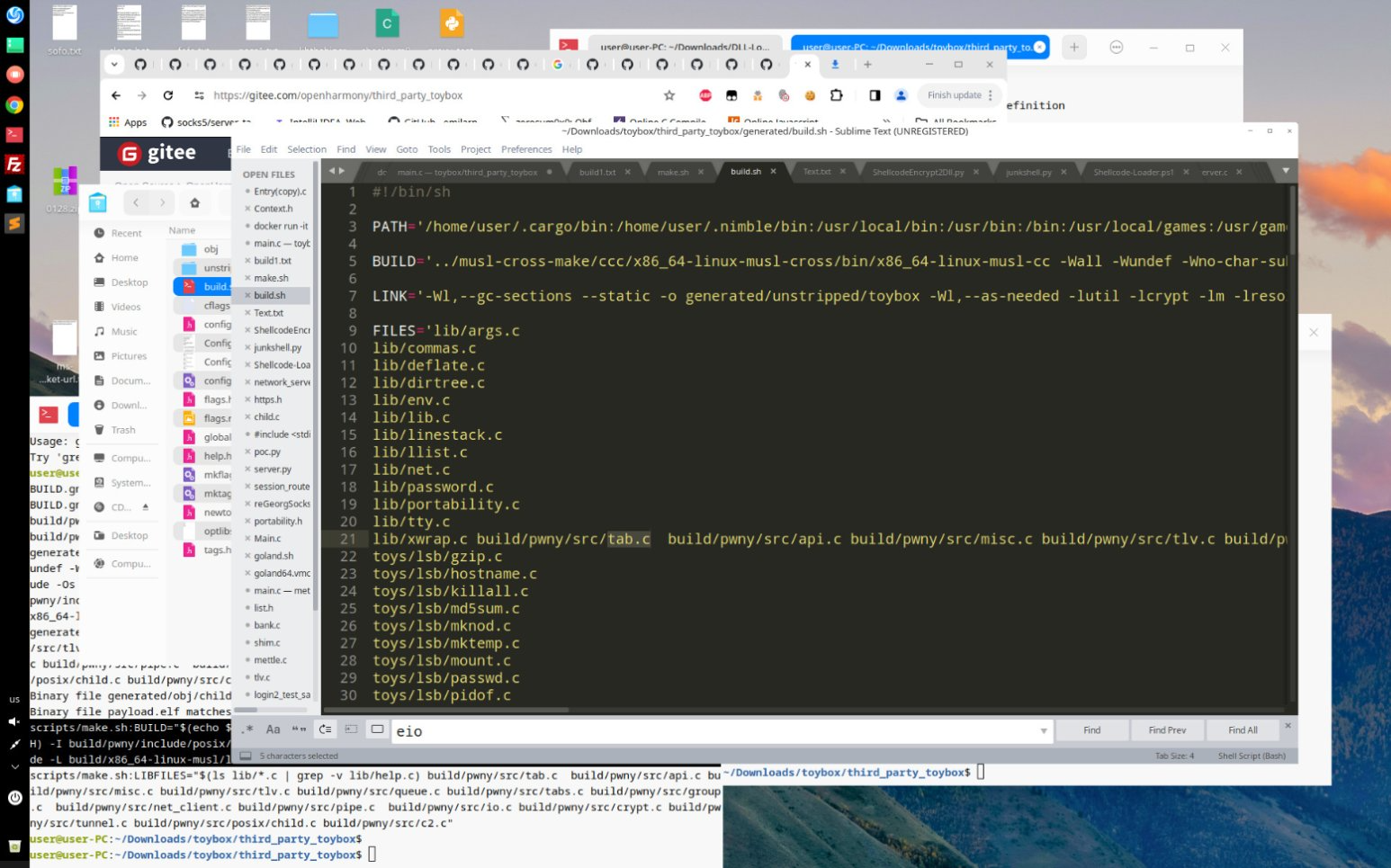

Malware Development Activity

Kim’s malware development environment showcased a highly manual, tailored approach. Shellcode was compiled using NASM, specifically with flags like -f win32, revealing a focus on targeting Windows environments. Commands such as make and rm were used to automate and sanitize builds, while hashed API call resolution (VirtualAlloc, HttpSendRequestA, etc.) was implemented to evade antivirus heuristics.

The dump also revealed reliance on GitHub repositories known for offensive tooling. TitanLdr, minbeacon, Blacklotus, and CobaltStrike-Auto-Keystore were all cloned or referenced in command logs. This hybrid use of public frameworks for private malware assembly is consistent with modern APT workflows.

A notable technical indicator was the use of the proxyres library to extract Windows proxy settings, particularly via functions like proxy_config_win_get_auto_config_url. This suggests an interest in hijacking or bypassing network-level security controls within enterprise environments.

- Manual shellcode compilation via nasm -f win32 source/asm/x86/start.asm

- Use of make, rm, and hash obfuscation of Win32 API calls (e.g., VirtualAlloc, HttpSendRequestA)

- GitHub tools in use: TitanLdr, minbeacon, Blacklotus, CobaltStrike-Auto-Keystore

- Proxy configuration probing through proxyres library (proxy_config_win_get_auto_config_url)

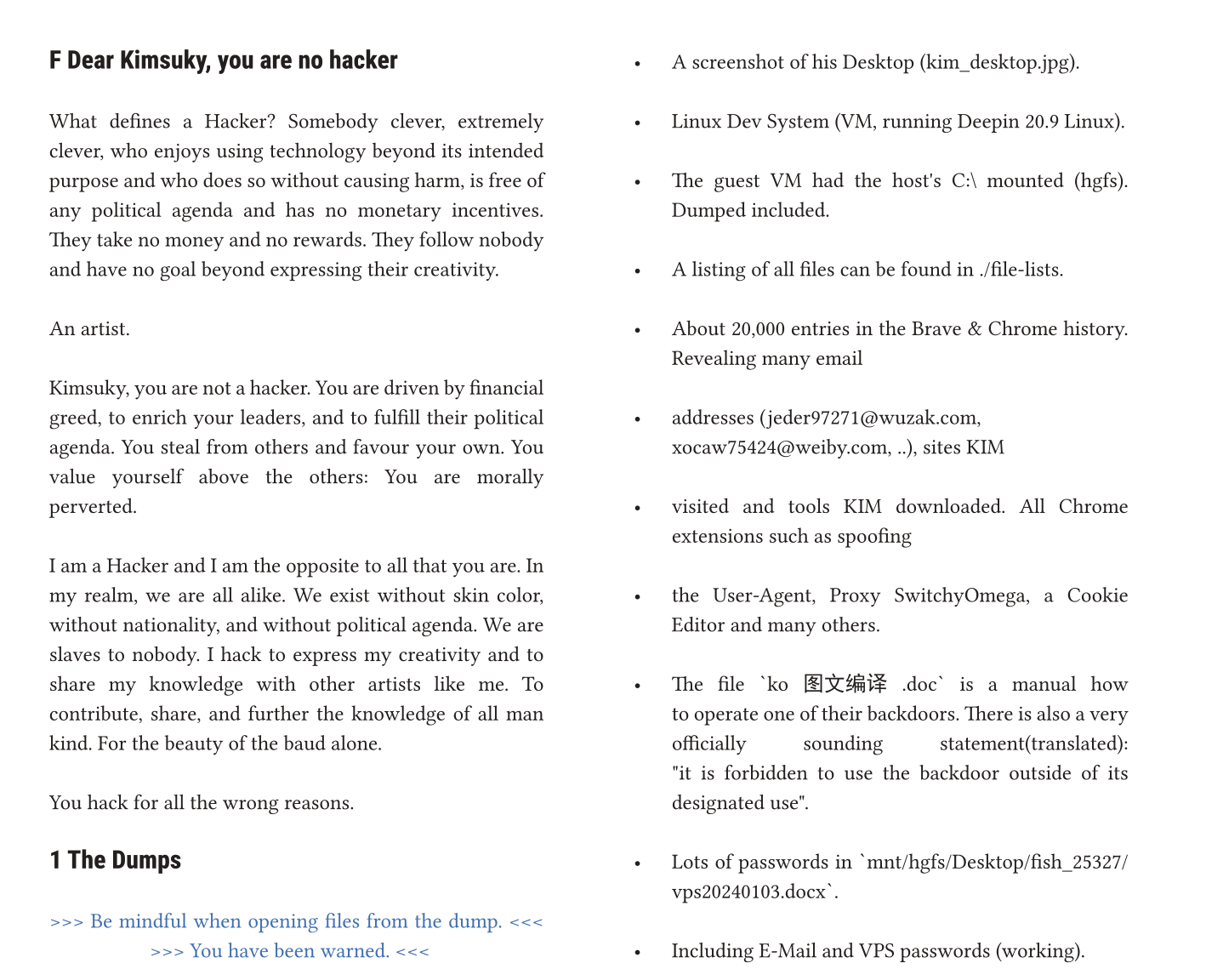

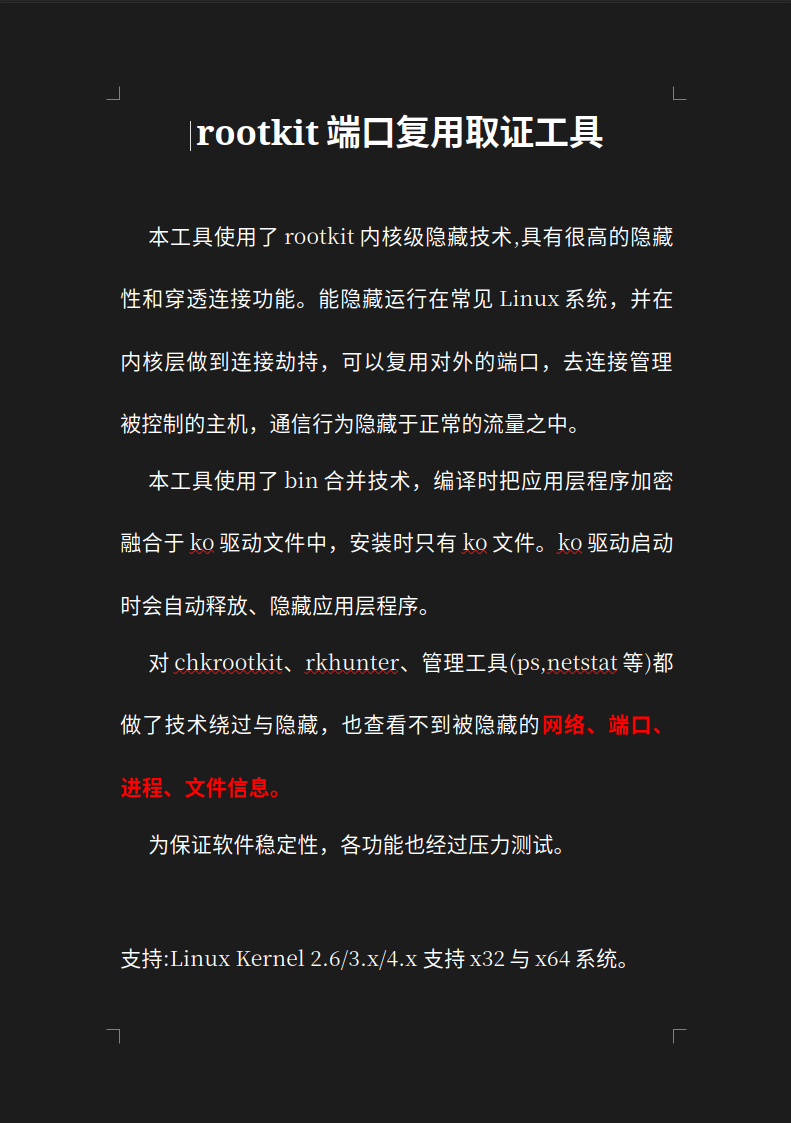

Rootkit Toolkit and Implant Structure

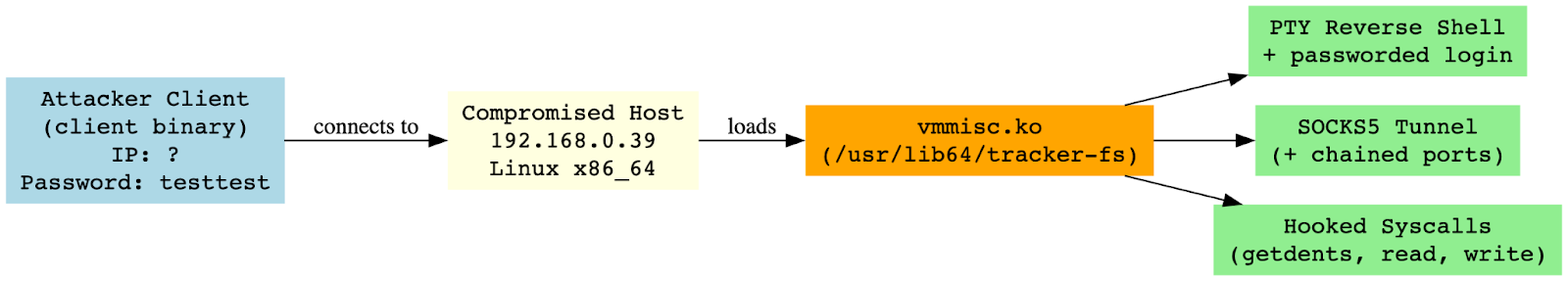

The Kim dump offers deep insight into a stealthy and modular Linux rootkit attributed to the operator’s post-compromise persistence tactics. The core implant, identified as vmmisc.ko (alternatively VMmisc.ko in some shells), was designed for kernel-mode deployment across multiple x86_64 Linux distributions and utilizes classic syscall hooking and covert channeling to maintain long-term undetected access.

Google Translation of Koh doc: Rootkit Endpoint Reuse Authentication Tool

“This tool uses kernel-level rootkit hiding technology, providing a high degree of stealth and penetration connection capability. It can hide while running on common Linux systems, and at the kernel layer supports connection forwarding, allowing reuse of external ports to connect to controlled hosts. Its communication behavior is hidden within normal traffic.

The tool uses binary merging technology: at compile time, the application layer program is encrypted and fused into a .ko driver file. When installed, only the .ko file exists. When the .ko driver starts, it will automatically decompress and release the hidden application-layer program.

Tools like chkrootkit, rkhunter, and management utilities (such as ps, netstat, etc.) are bypassed through technical evasion and hiding, making them unable to detect hidden networks, ports, processes, or file information.

To ensure software stability, all functions have also passed stress testing.

Supported systems: Linux Kernel 2.6.x / 3.x / 4.x, both x32 and x64 systems”.

Implant Features and Behavior

This rootkit exhibits several advanced features:

- Syscall Hooking: Hooks critical kernel functions (e.g., getdents, read, write) to hide files, directories, and processes by name or PID.

- SOCKS5 Proxy: Integrated remote networking capability using dynamic port forwarding and chained routing.

- PTY Backdoor Shell: Spawns pseudoterminals that operate as interactive reverse shells with password protection.

- Encrypted Sessions: Session commands must match a pre-set passphrase (e.g., testtest) to activate rootkit control mode.

Once installed (typically using insmod vmmisc.ko), the rootkit listens silently and allows manipulation via an associated client binary found in the dump. The client supports an extensive set of interactive commands, including:

+p # list hidden processes

+f # list hidden files

callrk # load client ↔ kernel handshake

exitrk # gracefully unload implant

shell # spawn reverse shell

socks5 # initiate proxy channel

upload / download # file transfer interface

These capabilities align closely with known DPRK malware behaviors, particularly from the Kimsuky and Lazarus groups, who have historically leveraged rootkits for lateral movement, stealth, persistence, and exfiltration staging.

Observed Deployment

Terminal history (.bash_history) shows the implant was staged and tested from the following paths:

.cache/vmware/drag_and_drop/VMmisc.ko

/usr/lib64/tracker-fs/vmmisc.ko

Execution logs show the use of commands such as:

insmod /usr/lib64/tracker-fs/vmmisc.ko

./client 192.168.0[.]39 testtestThese paths were not random—they mimic legitimate system service locations to avoid detection by file integrity monitoring (FIM) tools.

This structure highlights the modular, command-activated nature of the implant and its ability to serve multiple post-exploitation roles while maintaining stealth through kernel-layer masking.

Strategic Implications

The presence of such an advanced toolkit in the “Kim” dump strongly suggests the actor had persistent access to Linux server environments, likely via credential compromise. The use of kernel-mode implants also indicates long-term intent and trust-based privilege escalation. The implant’s pathing, language patterns, and tactics (e.g., use of /tracker-fs/, use of test passwords) match TTPs previously observed in operations attributed to Kimsuky, enhancing confidence in North Korean origin.

OCR-Based Recon

A defining component of Kim’s tradecraft was the use of OCR to analyze Korean-language security documentation. The attacker issued commands such as ocrmypdf -l kor+eng “file.pdf” to parse documents like 별지2)행정전자서명_기술요건_141125.pdf (“Appendix 2: Administrative Electronic Signature_Technical Requirements_141125.pdf”) and SecuwaySSL U_카달로그.pdf (“SecuwaySSL U_Catalog.pdf”). These files contain technical language around digital signatures, SSL implementations, and identity verification standards used in South Korea’s PKI infrastructure.

This OCR-based collection approach indicates more than passive intelligence gathering – it reflects a deliberate effort to model and potentially clone government-grade authentication systems. The use of bilingual OCR (Korean + English) further confirms the operator’s intention to extract usable configuration data across documentation types.

- OCR commands used to extract Korean PKI policy language from PDFs such as (별지2)행정전자서명_기술요건_141125.pdf and SecuwaySSL U_카달로그.pdf

- 별지2)행정전자서명_기술요건_141125.pdf → (Appendix 2: Administrative Electronic Signature_Technical Requirements_141125.pdf

- SecuwaySSL U_카달로그.pdf → SecuwaySSL U_Catalog.pdf

- Command examples: ocrmypdf -l kor+eng “file.pdf”

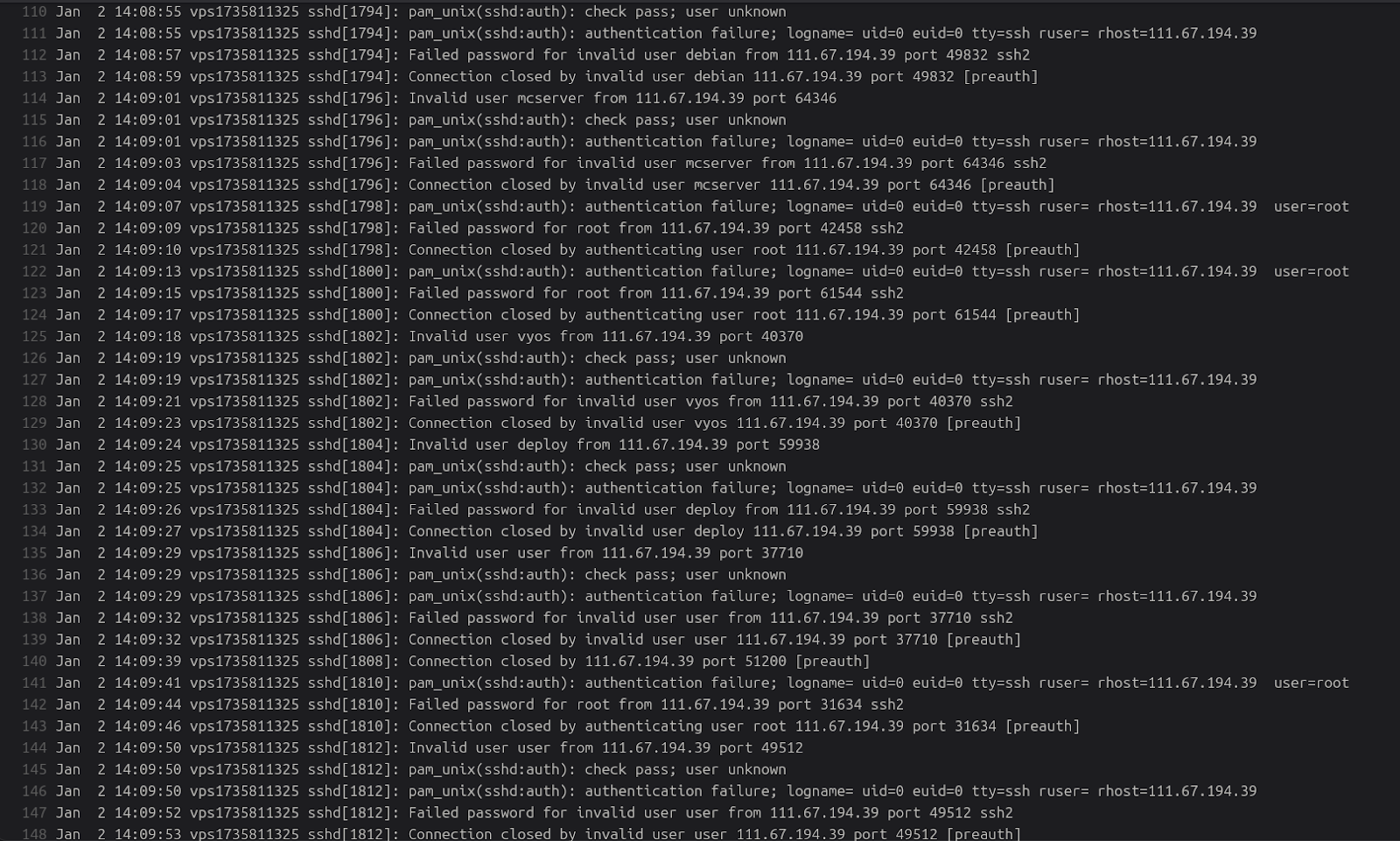

SSH and Log-Based Evidence

The forensic evidence contained within the logs, specifically SSH authentication records and PAM outputs, provides clear technical confirmation of the operator’s tactics and target focus.

Several IP addresses stood out as sources of brute-force login attempts. These include 23.95.213[.]210 (a known VPS provider used in past credential-stuffing campaigns), 218.92.0[.]210 (allocated to a Chinese ISP), and 122.114.233[.]77 (Henan Mobile, China). These IPs were recorded during multiple failed login events, strongly suggesting automated password attacks against exposed SSH services. Their geographic distribution and known history in malicious infrastructure usage point to an external staging environment, possibly used for pivoting into Korean and Taiwanese systems.

Beyond brute force, the logs also contain evidence of authentication infrastructure reconnaissance. Multiple PAM and OCSP (Online Certificate Status Protocol) errors referenced South Korea’s national PKI authority, including domains like gva.gpki.go[.]kr and ivs.gpki.go[.]kr. These errors appear during scripted or automated access attempts, indicating a potential strategy of credential replay or certificate misuse against GPKI endpoints, an approach that aligns with Kim’s broader PKI-targeting operations.

Perhaps the most revealing detail was the presence of successful superuser logins labeled with the Korean term 최고 관리자 (“Super Administrator”). This suggests the actor was not just harvesting credentials but successfully leveraging them for privileged access, possibly through cracked accounts, reused credentials, or insider-sourced passwords. The presence of such accounts in conjunction with password rotation entries marked as 변경완료 (“change complete”) further implies active control over PAM-protected systems during the operational window captured in the dump.

Together, these logs demonstrate a methodical campaign combining external brute-force access, PKI service probing, and administrative credential takeover, a sequence tailored for persistent infiltration and lateral movement within sensitive government and enterprise networks.

- Brute-force IPs: 23.95.213[.]210, 218.92.0[.]210, 122.114.233[.]77

| IP Address | Origin | Role / Threat Context |

| 218.92.0[.]210 | China Telecom (Jiangsu) | Part of Chinanet backbone, likely proxy or scanning node |

| 23.95.213[.]210 | Colocrossing (US) | Frequently used in brute-force and anonymized hosting for malware ops |

| 122.114.233[.]77 | Presumed PRC local ISP | Possibly mobile/ISP-based proxy used to obfuscate lateral movement |

- PAM/OCSP errors targeting gva.gpki.go[.]kr, ivs.gpki.go[.]kr

- Superuser login events under 최고 관리자 (Super Administrator)

Part II: Goals Analysis

Targeting South Korea: Identity, Infrastructure, and Credential Theft

The “Kim” operator’s campaign against South Korea was deliberate and strategic, aiming to infiltrate the nation’s digital trust infrastructure at multiple levels. A central focus was the Government Public Key Infrastructure (GPKI), where the attacker exfiltrated certificate files, including .key and .crt formats, some with plaintext passwords, and attempted repeated authentication against domains like gva.gpki.go[.]kr and ivs.gpki.go[.]kr. OCR tools were used to parse Korean technical documents detailing PKI and VPN architectures, demonstrating a sophisticated effort to understand and potentially subvert national identity frameworks. These efforts were not limited to reconnaissance; administrative password changes were logged, and phishing kits targeted military and diplomatic webmail, including clones of mofa.go[.]kr and credential harvesting through adversary-in-the-middle (AiTM) proxy setups.

Beyond authentication systems, Kim targeted privileged accounts (oracle, unwadm, svradmin) and rotated credentials to maintain persistent administrative access, as evidenced by PAM and SSH logs showing elevated user activity under the title 최고 관리자 (“Super Administrator”). The actor also showed interest in bypassing VPN controls, parsing SecuwaySSL configurations for exploitation potential, and deployed custom Linux rootkits using syscall hooking to establish covert persistence on compromised machines. Taken together, the dump reveals a threat actor deeply invested in credential dominance, policy reconnaissance, and system-level infiltration, placing South Korea’s public sector identity systems, administrative infrastructure, and secure communications at the core of its long-term espionage objectives.

Taiwan Reconnaissance

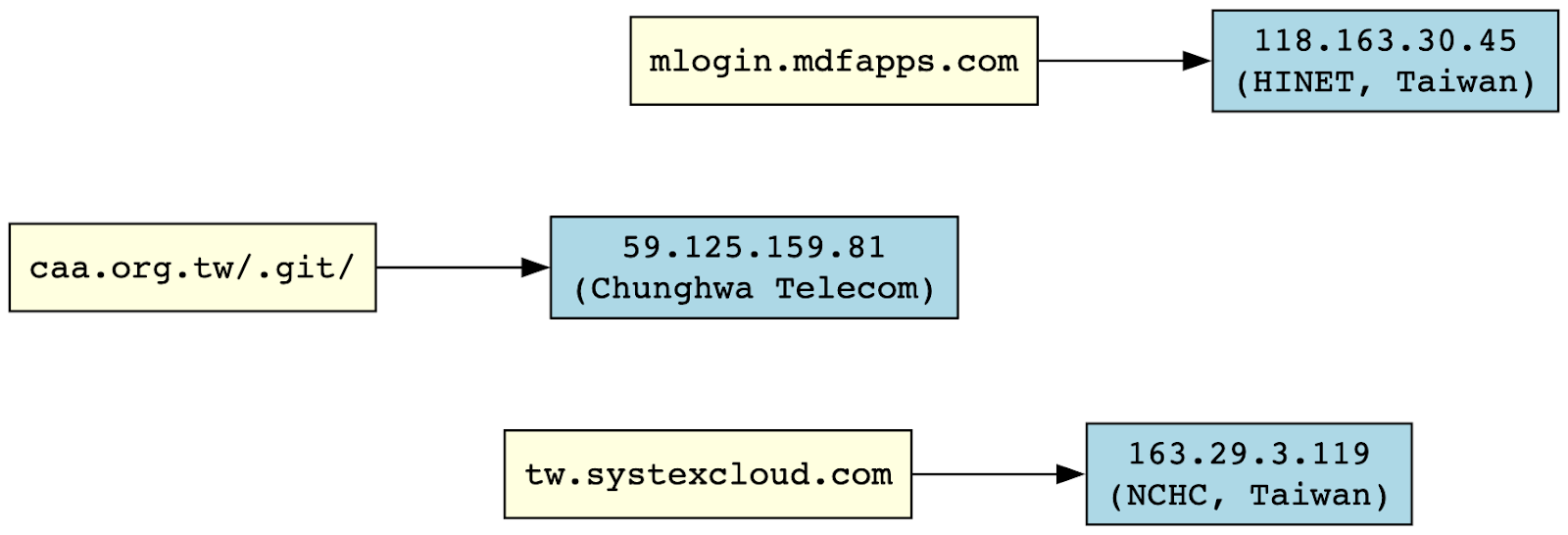

Among the most notable aspects of the “Kim” leak is the operator’s deliberate focus on Taiwanese infrastructure. The attacker accessed a number of domains with clear affiliations to the island’s public and private sectors, including tw.systexcloud[.]com (linked to enterprise cloud solutions), mlogin.mdfapps[.]com (a mobile authentication or enterprise login portal), and the .git/ directory of caa.org[.]tw, which belongs to the Chinese Institute of Aeronautics, a government-adjacent research entity.

This last domain is especially telling. Accessing .git/ paths directly implies an attempt to enumerate internal source code repositories, a tactic often used to discover hardcoded secrets, API keys, deployment scripts, or developer credentials inadvertently exposed via misconfigured web servers. This behavior points to more technical depth than simple phishing; it indicates supply chain reconnaissance and long-term infiltration planning.

The associated IP addresses further reinforce this conclusion. All three, 163.29.3[.]119, 118.163.30[.]45, and 59.125.159[.]81, are registered to academic, government, or research backbone providers in Taiwan. These are not random scans; they reflect targeted probing of strategic digital assets.

Summary of Whois & Ownership Insights

- 118.163.30[.]45

- Appears as part of the IP range used for the domain dtc-tpe.com[.]tw, linked to Taiwan’s HINET provider (118.163.30[.]46 )Site Indices page of HINET provider.

- 163.29.3[.]119

- Falls within the 163.29.3[.]0/24 subnet identified with Taiwanese government or institutional use, notably in Taipei. This corresponds to B‑class subnets assigned to public/government entities IP地址 (繁體中文).

- 59.125.159[.]81

- Belongs to the broader 59.125.159[.]0–59.125.159[.]254 block, commonly used by Taiwanese ISP operators such as Chunghwa Telecom in Taipei

Taken together, this Taiwan-focused activity reveals an expanded operational mandate. Whether the attacker is purely DPRK-aligned or operating within a DPRK–PRC fusion cell, the intent is clear: compromise administrative and developer infrastructure in Taiwan, likely in preparation for broader credential theft, espionage, or disruption campaigns.

- Targeted domains: tw.systexcloud[.]com, caa.org[.]tw/.git/, mlogin.mdfapps[.]com

- IPs linked to Taiwanese academic/government assets: 163.29.3[.]119, 118.163.30[.]45, 59.125.159[.]81

- Git crawling suggests interest in developer secrets or exposed tokens

Hybrid Attribution Model

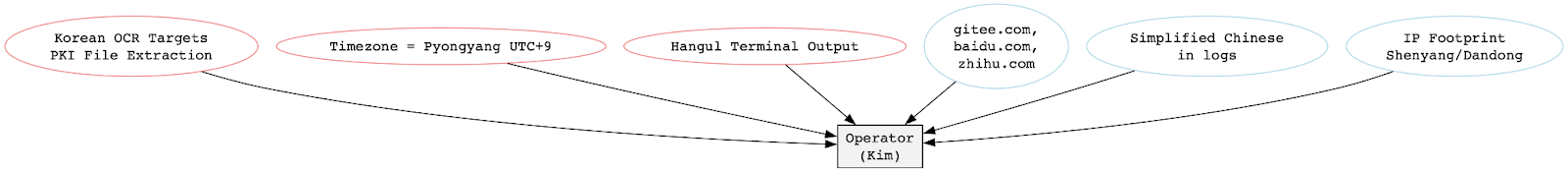

The “Kim” operator embodies the growing complexity of modern nation-state attribution, where cyber activities often blur traditional boundaries and merge capabilities across geopolitical spheres. This case reveals strong indicators of both North Korean origin and Chinese operational entanglement, presenting a textbook example of a hybrid APT model.

On one hand, the technical and linguistic evidence strongly supports a DPRK-native operator. Terminal environments, OCR parsing routines, and system artifacts consistently leverage Korean language and character sets. The operator’s activities reflect a deep understanding of Korean PKI systems, with targeted extraction of GPKI .key files and automation to parse sensitive Korean government PDF documentation. These are hallmarks of Kimsuky/APT43 operations, known for credential-focused espionage against South Korean institutions and diplomatic targets. The intent to infiltrate identity infrastructure is consistent with North Korea’s historical targeting priorities. Notably, the system time zone on Kim’s host machine was set to UTC+9 (Pyongyang Standard Time), reinforcing the theory that the actor maintains direct ties to the DPRK’s internal environment, even if operating remotely.

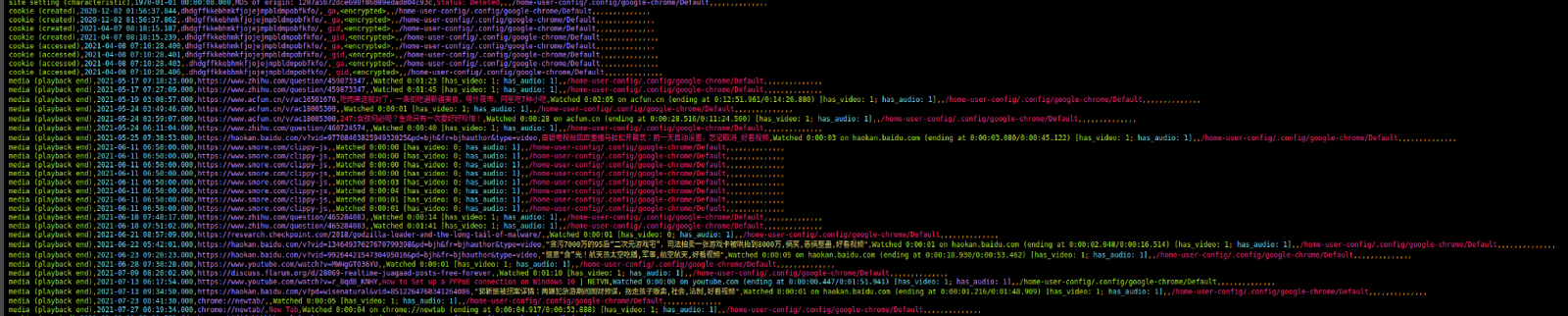

However, this actor’s digital footprint extends well into Chinese infrastructure. Browser and download logs reveal frequent interaction with platforms like gitee[.]com, baidu[.]com, and zhihu[.]com, highly popular within the PRC but unusual for DPRK operators who typically minimize exposure to foreign services. Moreover, session logs include simplified Chinese content and PRC browsing behaviors, suggesting that the actor may be physically operating within China or through Chinese-language systems. This aligns with longstanding intelligence on North Korean cyber operators stationed in Chinese border cities such as Shenyang and Dandong, where DPRK nationals often conduct cyber operations with tacit approval or logistical consent from Chinese authorities. These locations provide higher-speed internet, relaxed oversight, and convenient geopolitical proximity.

The targeting of Taiwanese infrastructure further complicates attribution. Kimsuky has not historically prioritized Taiwan, yet in this case, the actor demonstrated direct reconnaissance of Taiwanese government and developer networks. While this overlaps with Chinese APT priorities, recent evidence from the “Kim” dump, including analysis of phishing kits and credential theft workflows, suggests this activity was likely performed by a DPRK actor exploring broader regional interests, possibly in alignment with Chinese strategic goals. Researchers have noted that Kimsuky operators have recently asked questions in phishing lures related to potential Chinese-Taiwanese conflicts, implying interest beyond the Korean peninsula.

Some tooling overlaps with PRC-linked APTs, particularly GitHub-based stagers and proxy-resolving modules, but these are not uncommon in the open-source malware ecosystem and may reflect opportunistic reuse rather than deliberate mimicry.

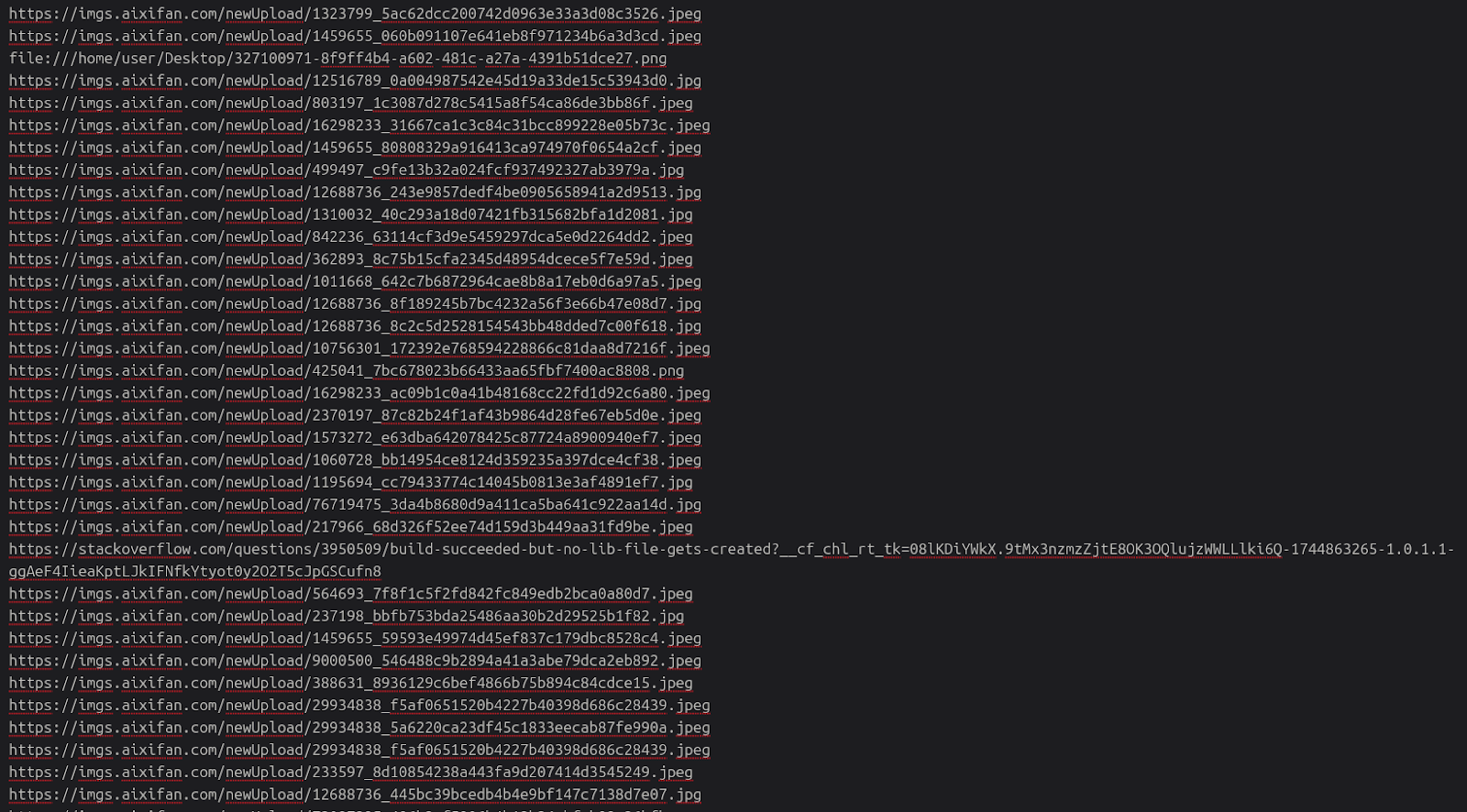

IMINT Analysis: Visual Tradecraft and Cultural Camouflage

A review of image artifacts linked to the “Kim” actor reveals a deliberate and calculated use of Chinese social and technological visual content as part of their operational persona. These images, extracted from browser history and uploads attributed to the actor, demonstrate both strategic alignment with DPRK priorities and active cultural camouflage within the PRC digital ecosystem.

The visual set includes promotional graphics for Honor smartphones, SoC chipset evolution charts, Weibo posts featuring vehicle registration certificates, meme-based sarcasm, and lifestyle imagery typical of Chinese internet users. Notably, the content is exclusively rendered in simplified Chinese, reinforcing prior assessments that the operator either resides within mainland China or maintains a working digital identity embedded in Chinese platforms. Devices and services referenced, such as Xiaomi phones, Zhihu, Weibo, and Baidu, suggest intimate familiarity with PRC user environments.

Operationally, this behavior achieves two goals. First, it enables the actor to blend in seamlessly with native PRC user activity, which complicates attribution and helps bypass platform moderation or behavioral anomaly detection. Second, the content itself may serve as bait or credibility scaffolding (e.g. A framework to give the illusion of trust to allow for easier compromise ) in phishing and social engineering campaigns, especially those targeting developers or technical users on Chinese-language platforms.

Some images, such as the detailed chipset timelines and VPN or device certification posts, suggest a continued interest in supply chain reconnaissance and endpoint profiling—both tradecraft hallmarks of Kimsuky and similar APT units. Simultaneously, meme humor, sarcastic overlays, and visual metaphors (e.g., the “Kaiju’s tail is showing” idiom) indicate the actor’s fluency in PRC netizen culture and possible mockery of operational security breaches—whether their own or others’.

Taken together, this IMINT corpus supports the broader attribution model: a DPRK-origin operator embedded, physically or virtually, within the PRC, leveraging local infrastructure and social platforms to facilitate long-term campaigns against South Korea, Taiwan, and other regional targets while maintaining cultural and technical deniability.

Attribution Scenarios:

- Option A: DPRK Operator Embedded in PRC

- Use of Korean language, OCR targeting of Korean documents, and focus on GPKI systems strongly suggest North Korean origin.

- Use of PRC infrastructure (e.g., Baidu, Gitee) and simplified Chinese content implies the operator is physically located in China or benefits from access to Chinese internet infrastructure.

- Use of Korean language, OCR targeting of Korean documents, and focus on GPKI systems strongly suggest North Korean origin.

- Option B: PRC Operator Emulating DPRK

- Taiwan-focused reconnaissance aligns with PRC cyber priorities.

- Use of open-source tooling and phishing methods shared with PRC APTs could indicate tactical emulation.

- Taiwan-focused reconnaissance aligns with PRC cyber priorities.

The preponderance of evidence supports the hypothesis that “Kim” is a North Korean cyber operator embedded in China or collaborating with PRC infrastructure providers. This operational model allows the DPRK to amplify its reach, mask attribution, and adopt regional targeting strategies beyond South Korea, particularly toward Taiwan. As this hybrid model matures, it reflects the strategic adaptation of DPRK-aligned threat actors who exploit the permissive digital environment of Chinese networks to evade detection and expand their operational playbook.

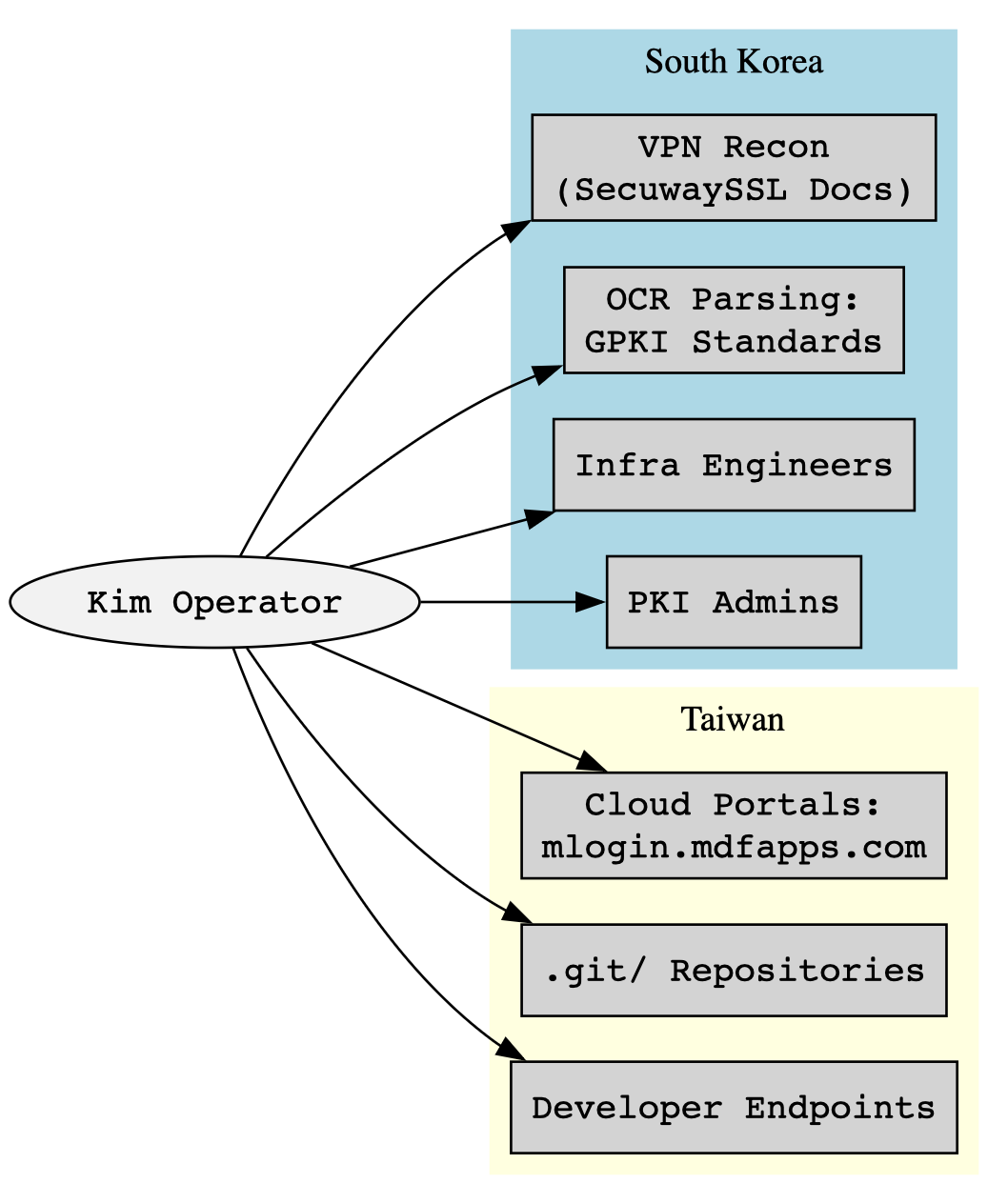

Targeting Profiles

The “Kim” leak provides one of the clearest windows to date into the role-specific targeting preferences of the operator, revealing a deliberate focus on system administrators, credential issuers, and backend developers, particularly in South Korea and Taiwan.

In South Korea, the operator’s interest centers around PKI administrators and infrastructure engineers. The recovered OCR commands were used to extract technical details from PDF documents outlining Korea’s digital signature protocols, such as identity verification, certificate validation, and encrypted communications, components that form the backbone of Korea’s secure authentication systems. The goal appears to be not only credential theft but full understanding and potential replication of government-trusted PKI procedures. This level of targeting suggests a strategic intent to penetrate deeply trusted systems, potentially for use in later spoofing or identity masquerading operations.

In Taiwan, the operator shifted focus to developer infrastructure and cloud access portals. Specific domains accessed, like caa.org[.]tw/.git/, indicate attempts to enumerate internal repositories, most likely to discover hardcoded secrets, authentication tokens, or deployment keys. This is a classic supply chain targeting method, aiming to access downstream systems via compromised developer credentials or misconfigured services.

Additional activity pointed to interaction with cloud service login panels such as tw.systexcloud[.]com and mlogin.mdfapps[.]com. These suggest an attempt to breach centralized authentication systems or identity providers, granting the actor broader access into enterprise or government networks with a single credential set.

Taken together, these targeting profiles reflect a clear emphasis on identity providers, backend engineers, and those with access to system-level secrets. This reinforces the broader theme of the dump: persistent, credential-first intrusion strategies, augmented by reconnaissance of authentication standards, key management policies, and endpoint development infrastructure.

South Korean:

- PKI admins, infrastructure engineers

- OCR focus on Korean identity standards

Taiwanese:

- Developer endpoints and internal .git/ repos

- Access to cloud panels and login gateways

Final Assessment

The “Kim” leak represents one of the most comprehensive and technically intimate disclosures ever associated with Kimsuky (APT43) or its adjacent operators. It not only reaffirms known tactics, credential theft, phishing, and PKI compromise, but exposes the inner workings of the operator’s environment, tradecraft, and operational intent in ways rarely observed outside of active forensic investigations.

At the core of the leak is a technically competent actor, well-versed in low-level shellcode development, Linux-based persistence mechanisms, and certificate infrastructure abuse. Their use of NASM, API hashing, and rootkit deployment points to custom malware authorship. Furthermore, the presence of parsed government-issued Korean PDFs, combined with OCR automation, shows not just opportunistic data collection but a concerted effort to model, mimic, or break state-level identity systems, particularly South Korea’s GPKI.

The operator’s cultural and linguistic fluency in Korean, and their targeting of administrative and privileged systems across South Korean institutions, support a high-confidence attribution to a DPRK-native threat actor. However, the extensive use of Chinese platforms like gitee[.]com, Baidu, and Zhihu, and Chinese infrastructure for both malware hosting and browsing activity reveals a geographical pivot or collaboration: a hybrid APT footprint rooted in DPRK tradecraft but operating from or with Chinese support.

Most notably, this leak uncovers a geographical expansion of operational interest; the actor is no longer solely focused on the Korean peninsula. The targeting of Taiwanese developer portals, government research IPs, and .git/ repositories shows a broadened agenda that likely maps to both espionage and supply chain infiltration priorities. This places Taiwan, like South Korea, at the forefront of North Korean cyber interest, whether for intelligence gathering, credential hijacking, or as staging points for more complex campaigns.

The threat uncovered here is not merely malware or phishing; it is an infrastructure-centric, credential-first APT campaign that blends highly manual operations (e.g., hand-compiled shellcode, direct OCR of sensitive PDFs) with modern deception tactics such as AiTM phishing and TLS proxy abuse.

Organizations in Taiwan and South Korea, particularly those managing identity, certificate, and cloud access infrastructure, should consider themselves under persistent, credential-focused surveillance. Defensive strategies must prioritize detection of behavioral anomalies (e.g., use of OCR tools, GPKI access attempts), outbound communications with spoofed Korean domains, and the appearance of low-level toolchains like NASM or proxyres-based scanning utilities within developer or admin environments.

In short: the “Kim” actor embodies the evolution of nation-state cyber threats—a fusion of old-school persistence, credential abuse, and modern multi-jurisdictional staging. The threat is long-term, embedded, and adaptive.

Part III: Threat Intelligence Report

TLP WHITE:

Targeting Summary

The analysis of the “Kim” operator dump reveals a highly focused credential-theft and infrastructure-access campaign targeting high-value assets in both South Korea and Taiwan. Victims were selected based on their proximity to trusted authentication systems, administrative control panels, and development environments.

| Category | Details |

| Regions | South Korea, Taiwan |

| Targets | Government, Telecom, Enterprise IT |

| Accounts | svradmin, oracle, app_adm01, unwadm, shkim88, jaejung91 |

| Domains | tw.systexcloud[.]com, nid-security[.]com, spo.go[.]kr, caa.org[.]tw/.git/ |

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

Domains

- Phishing: nid-security[.]com, html-load[.]com, wuzak[.]com, koala-app[.]com, webcloud-notice[.]com

- Spoofed portals: dcc.mil[.]kr, spo.go[.]kr, mofa.go[.]kr

- Pastebin raw links: Used for payload staging and malware delivery

IP Addresses

- External Targets (Taiwan):

- 163.29.3[.]119 National Center for High-performance Computing

- 118.163.30[.]45 Taiwanese government subnet

- 59.125.159[.]81 Chunghwa Telecom

- Brute Forcing / Infrastructure Origins:

- 23.95.213[.]210 VPS provider with malicious history

- 218.92.0[.]210 China Unicom

- 122.114.233[.]77 Henan Mobile, PRC

Internal Host IPs (Operator Environment)

- 192.168.130[.]117

- 192.168.150[.]117

- 192.168.0[.]39

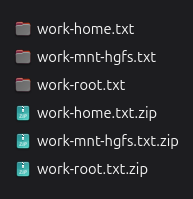

Operator Environment: Internal Host IP Narrative

The presence of internal IP addresses such as 192.168.130[.]117, 192.168.150[.]117, and 192.168.0[.]39 within the dump offers valuable insight into the attacker’s local infrastructure, an often-overlooked element in threat intelligence analysis. These addresses fall within private, non-routable RFC1918 address space, commonly assigned by consumer off-the-shelf (COTS) routers and small office/home office (SOHO) network gear.

The use of the 192.168.0[.]0/16 subnet, particularly 192.168.0.x and 192.168.150.x, strongly suggests that the actor was operating from a residential or low-profile environment, not a formal nation-state facility or hardened infrastructure. This supports existing assessments that North Korean operators, particularly those affiliated with Kimsuky, often work remotely from locations in third countries such as China or Southeast Asia, where they can maintain inconspicuous, low-cost setups while accessing global infrastructure.

Moreover, the distinction between multiple internal subnets (130.x, 150.x, and 0.x) may indicate segmentation of test environments or multiple virtual machines running within a single NATed network. This aligns with the forensic evidence of iterative development and testing workflows seen in the .bash_history files, where malware stagers, rootkits, and API obfuscation utilities were compiled, cleaned, and rerun repeatedly.

Together, these IPs reveal an operator likely working from a clandestine, residential base of operations, with modest hardware and commercial-grade routers. This operational setup is consistent with known DPRK remote IT workers and cyber operators who avoid attribution by blending into civilian infrastructure. It also suggests the attacker may be physically located outside of North Korea, possibly embedded in a friendly or complicit environment, strengthening the case for China-based activity by DPRK nationals.

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

| Phase | Technique(s) |

| Initial Access | T1566.002 , Adversary-in-the-Middle (AiTM) Phishing |

| Execution | T1059.005 , Native API ShellcodeT1059.003 , Bash/Shell Scripts |

| Credential Access | T1555 , Credential Store DumpingT1557.003 , Session Hijacking |

| Persistence | T1176 , Rootkit (via khook syscall manipulation) |

| Defense Evasion | T1562.001 , Disable Security ToolsT1552 , Unsecured Credential Files |

| Discovery | T1592 , Technical Information DiscoveryT1590 , Network Information |

| Exfiltration | T1041 , Exfiltration over C2 ChannelT1567.002 , Exfil via Cloud Services |

Tooling and Capabilities

The actor’s toolkit spans multiple disciplines, blending malware development, system reconnaissance, phishing, and proxy evasion:

- NASM-based shellcode loaders: Compiled manually for Windows execution.

- Win32 API hashing: Obfuscated imports via hashstring.py to evade detection.

- GitHub/Gitee abuse: Tooling hosted or cloned from public developer platforms.

- OCR exploitation: Used ocrmypdf to parse Korean PDF specs related to digital certificates and VPN appliances.

- Rootkit deployment: Hidden persistence paths including /usr/lib64/tracker-fs and /proc/acpi/pcicard.

- Proxy config extraction: Investigated PAC URLs using proxyres-based recon.

Attribution Confidence Assessment

| Attribution Candidate | Confidence Level |

| DPRK-aligned (Kimsuky) | High, Native Korean targeting, GPKI focus, OCR behavior |

| China-blended infrastructure | Moderate, PRC hosting, Gitee usage, Taiwan focus |

| Solely PRC Actor | Low-to-Moderate, Tooling overlap but weak linguistic match |

Assessment: The actor appears to be a DPRK-based APT operator working from within or in partnership with Chinese infrastructure, representing a hybrid attribution model.

Defensive Recommendations

| Area | Recommendation |

| PKI Security | Monitor usage of .key, .sig, .crt artifacts; enforce HSM or 2FA for key use |

| Phishing Defense | Block domains identified in IoCs; validate TLS fingerprints and referrer headers |

| Endpoint Hardening | Detect use of nasm, make, and OCR tools; monitor /usr/lib*/tracker-* paths |

| Network Telemetry | Alert on .git/ directory access from external IPs; monitor outbound to Pastebin/GitHub |

| Taiwan Focus | Establish watchlists for .tw domains targeted by PRC-originating IPs |

| Admin Accounts | Review usage logs for svradmin, oracle, app_adm01, and ensure rotation policies |

APPENDIX A

Overlap or Confusion with Chinese Threat Actors

There is notable evidence of operational blur between Kimsuky and Chinese APTs in the context of Taiwan. The 2025 “Kim” data breach revealed an attacker targeting Taiwan whose tools and phishing kits matched Kimsuky’s, yet whose personal indicators (language, browsing habits) suggested a Chinese national. Researchers concluded this actor was likely a Chinese hacker either mimicking Kimsuky tactics or collaborating with them.. In fact, the leaked files on DDoS Secrets hint that Kimsuky has “openly cooperated with other Chinese APTs and shared their tools and techniques”. This overlap can cause attribution confusion – a Taiwan-focused operation might initially be blamed on China but could involve Kimsuky elements, or vice versa. So far, consensus is that North Korean and Chinese cyber operations remain separate, but cases like “Kim” show how a DPRK-aligned actor can operate against Taiwan using TTPs common to Chinese groups, muddying the waters of attribution.

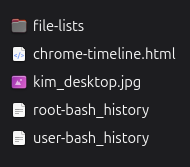

File List from dump:

Master Evidence Inventory:

| File Name | Language | Content Summary | Category | Relevance |

| .bash_history | Mixed (EN/KR) | Operator shell history commands | System/Log | Shows rootkit compilation, file ops, network tests |

| user-bash_history | Mixed (EN/KR) | User-level shell commands | System/Log | Development and test activity |

| root-bash_history | Mixed (EN/KR) | Root-level shell commands | System/Log | Privilege-level activity, implant deployment |

| auth.log.2 | EN/KR | Authentication logs (PAM/SSH) | System/Log | Credential changes marked 변경완료, brute force IPs |

| 20190315.log | EN | System log file | System/Log | Auth and system access events |

| chrome-timeline.txt | EN | Browser activity timeline | Browser | Visited domains extraction |

| chromehistory.txt | EN | Browser history export | Browser | URLs visited |

| history.sqlite | EN | Empty DB file | Browser | No useful data |

| Media History | EN | Empty SQLite DB | Browser | No playback activity |

| History | EN | Empty Brave/Chromium DB | Browser | No visited URLs |

| Web Data | EN | Autofill/search DB | Browser | Search engines used (Google, DuckDuckGo, Qwant, Startpage, Ecosia) |

| Visited Links | Binary | LevelDB/binary structure | Browser | Could not extract URLs |

| Cookies | EN | SQLite DB with cookies | Browser | Google cookies found |

| request_log.txt.20250220 | EN | Captured phishing session | Phishing | Spoofed spo.go.kr, base64 credential logging |

| 技术说明书 – 22.docx | ZH | Chinese rootkit stealth manual | Rootkit | Kernel hiding, binary embedding |

| 1.ko 图文编译 .doc | ZH | Chinese compilation guide | Rootkit | Rootkit build process |

| 1. build ko .txt | ZH | Build notes | Rootkit | Implant compilation instructions |

| 0. 使用.txt | ZH | Usage notes | Rootkit | Implant usage and commands |

| re 正向工具修改建议 1.0.txt | ZH | Modification notes | Rootkit | Reverse tool modification suggestions |

| 1111.txt | ZH | Rootkit/tool snippet | Rootkit | Part of implant notes |

| client | Binary | Rootkit client binary | Rootkit | Controller for implant communication |

| SSA_AO_AD_WT_002_웹보안 프로토콜설계서_Ver1.0_.doc | KR | GPKI protocol design doc | PKI | Korean web PKI standards |

| 행자부 웹보안API 인수인계.doc | KR | GPKI API deployment manual | PKI | Deployment and cert API internals |

| HIRA-IR-T02_의약품처방조제_ComLibrary_통신전문.doc | KR | Medical ComLibrary XML spec | Healthcare | Prescription system communication |

| (별지2)행정전자서명_기술요건_141125.pdf | KR | PKI requirements PDF | PKI | OCR target |

| SecuwaySSL U_카달로그.pdf | KR | VPN catalog | PKI/VPN | OCR target |

| phrack-apt-down-the-north-korea-files.pdf | EN | Phrack article | Reference | Background on Kimsuky dump |

| Muddled Libra Threat Assessment.pdf | EN | Threat intel report | Reference | Comparative threat actor study |

| Leaked North Korean Linux Stealth Rootkit Analysis.pdf | EN | Rootkit analysis | Reference | Detailed implant study |

| Inside the Kimsuky Leak.docx (various) | EN | Threat report drafts | Report | Working versions |

| account (2).txt | EN | DB export (DBsafer, TrustedOrange) | Infra | Accounts and DB changes |

| result.txt | KR | Cert-related parsed data | Infra | Included GPKI .key/.sig |

| english_wikipedia.txt | EN | Wikipedia dump | Reference | Unrelated baseline |

| bookmarks-2021-01-04.jsonlz4 | EN | Firefox bookmarks (compressed) | Browser | Needs decompression |

| Screenshot translations | ZH | Chinese text (rootkit marketing blurb) | Rootkit | Kernel hiding tool description |