From Laptops to Laundromats: How DPRK IT Workers Infiltrated the Global Remote Economy

Introduction

Over the last five years, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) has transitioned from smash-and-grab cryptocurrency raids to a more covert, scalable model of economic warfare: the global deployment of disguised IT workers.

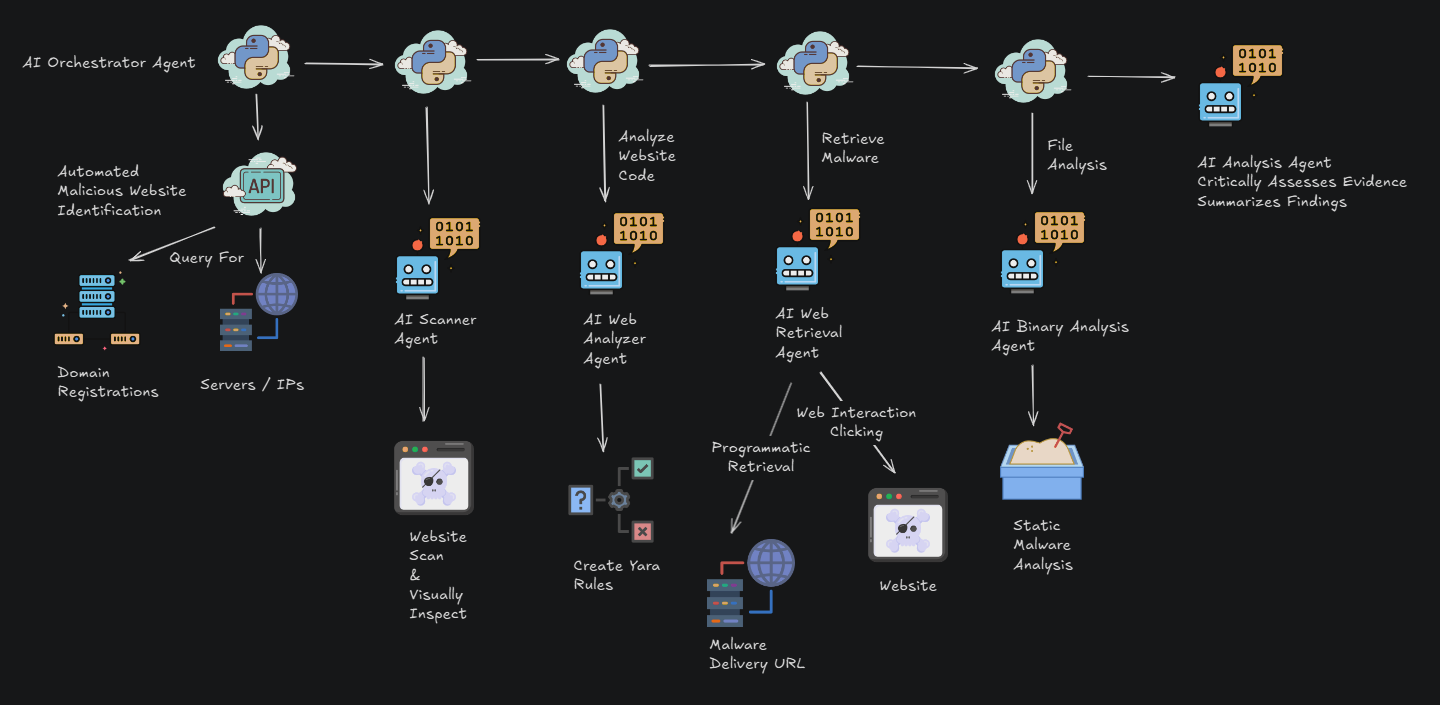

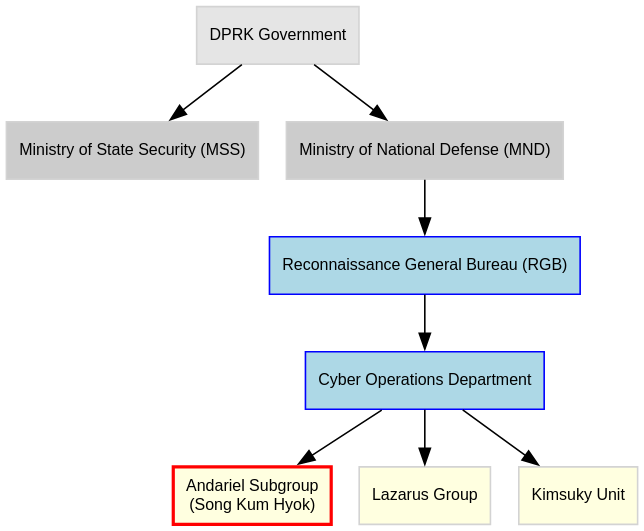

Orchestrated by elite units under the Reconnaissance General Bureau (RGB), these operatives acquire remote employment with U.S. and international tech firms using forged or stolen identities. Once embedded, they receive crypto-based salaries and redirect those earnings into the DPRK’s economy via a network of laundering nodes, front companies, and domain infrastructure.

This report maps the entire ecosystem: key actors, GitHub aliases, laundering flows, shell companies, fake domains, platform infiltration, wallet infrastructure, and global enablers. We also examine the national security implications of the scheme, as well as how lax corporate hiring standards allowed North Korean operatives not just to get paid, but to access critical infrastructure, intellectual property, and production code.

Key Actors and Their Roles

Central Command: Song Kum Hyok & the Andariel Subgroup

At the operational core of North Korea’s disguised IT labor campaign stands Song Kum Hyok, a senior officer within the Andariel subgroup, one of the Reconnaissance General Bureau’s (RGB) elite cyber units. The RGB, North Korea’s main foreign intelligence service, directs both offensive cyber operations and covert economic warfare efforts, and Song’s role straddles both.

Hyok has long been involved in digital identity manipulation, remote access infrastructure, and dark market employment pipelines. Intelligence archives suggest that before assuming his current role, he was linked to multiple Andariel operations involving ransomware staging servers and social engineering against South Korean financial firms.

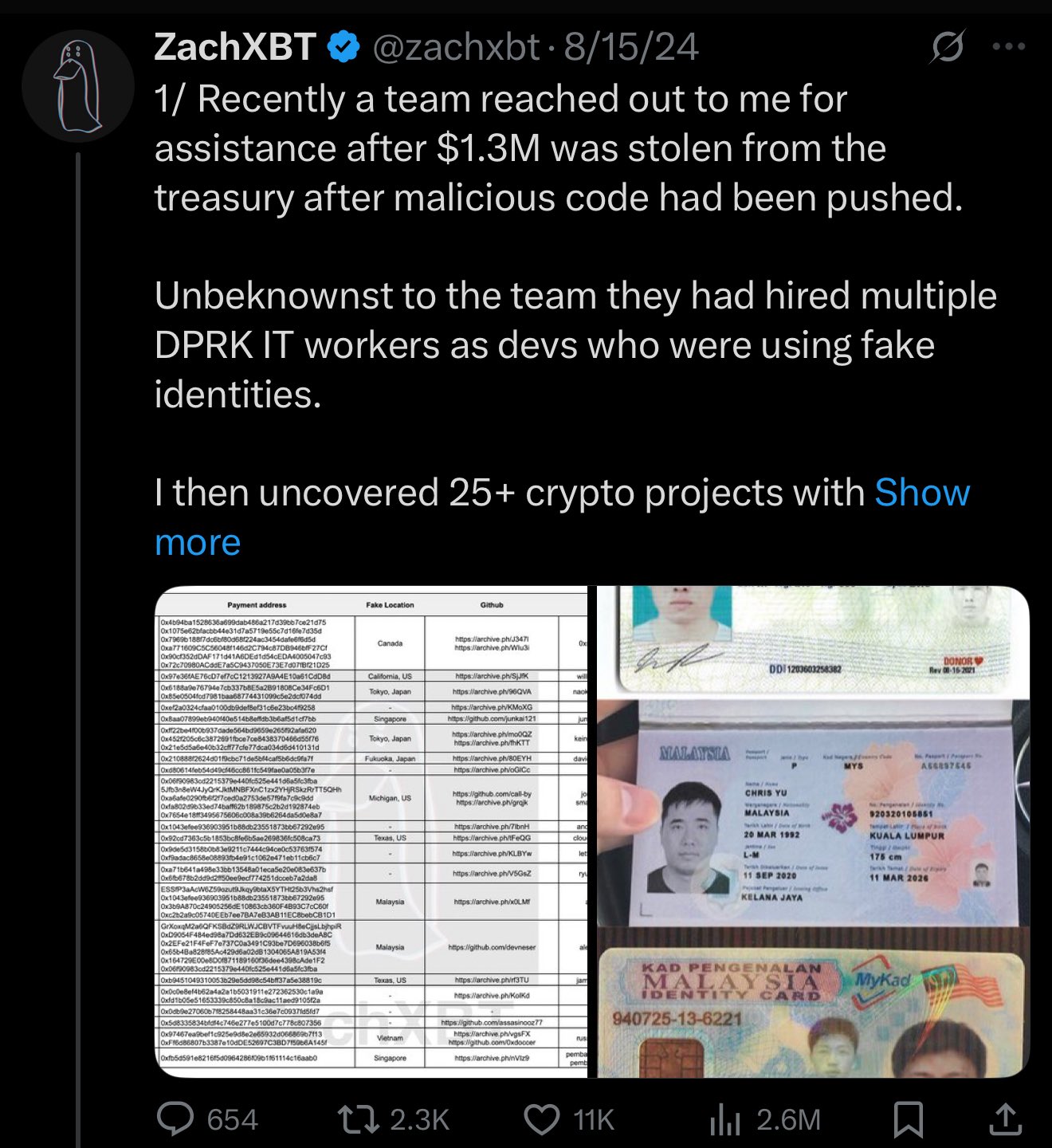

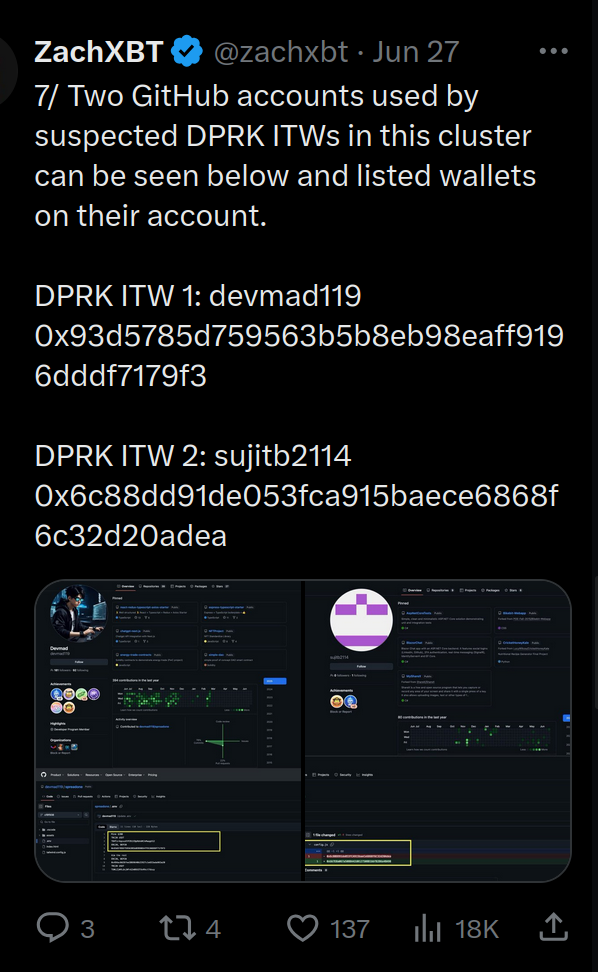

In the IT worker scheme, Song Kum Hyok is the strategic coordinator of identity theft and resume forgery, enabling North Korean engineers to present themselves as legitimate U.S. based freelancers. North Korea’s decentralized cyber-labor offensive hinges on stolen and curated identities—complete with names like Joshua Palmer, Sandy Nguyen, and GitHub handles such as devmad119 and sujitb2114. These identities often include verified Know Your Customer (KYC) data: Social Security numbers, clean background checks, and even Green Card scans, sourced from data breaches or underground markets.

Operatives use these identity packages to craft professional-grade resumes and LinkedIn profiles, frequently enhanced with AI-generated content and real or fabricated employment histories. They apply to remote jobs on freelancing platforms such as Upwork, Ureed, or the now-defunct Nabbesh, exploiting weak or automated verification and HR onboarding systems in U.S. companies.

Once hired, they gain access to internal tools and sensitive systems: GitHub repositories, Slack channels, financial dashboards, CI/CD pipelines, and privileged cloud infrastructure. From this vantage point, they can siphon intellectual property, embed backdoors, and surveill company operations—all while appearing to be legitimate remote hires. This seamless path, from stolen identity to embedded insider—is the operational backbone of Pyongyang’s covert cyber-espionage labor force.

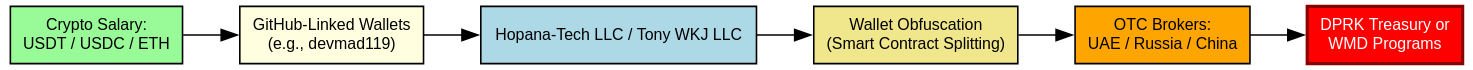

Once North Korean operatives are embedded in foreign companies, their wages, often paid in cryptocurrencies as well as financial transfers through banks are routed through a meticulously layered laundering process. The first stop is typically a GitHub-linked wallet address associated with the operative’s fake identity (e.g., aliases like “devmad119” or “Joshua Palmer”). From there, the funds may flow into front companies such as Hopana-Tech LLC which act as legitimate salary processors. To further obscure the money trail, salaries are split across multiple wallets using automated smart contracts, a tactic designed to fragment and anonymize the source of funds. Finally, the dispersed assets are aggregated and cashed out via over-the-counter (OTC) crypto brokers based in Russia, the UAE, and China, jurisdictions known for permissive financial enforcement. This end-to-end pipeline creates a resilient and stealthy mechanism for the DPRK to funnel hard currency back into its economy while bypassing international sanctions.

Hyok’s innovation lies in combining AI-generated job profiles with pre-cleared identity data and military operational discipline. Under his supervision, the scheme has moved from ad hoc fraud to a scalable, persistent economic attack model yielding millions of dollars annually for North Korea’s weapons programs while hiding in plain sight inside the legitimate global economy.

U.S. Frontman: Kejia Wang

From a quiet address in Edison, New Jersey, Kejia Wang, also known as Tony Wang, ran one of the most critical nodes in North Korea’s international cyber-laundering apparatus. His residence at 65 Idlewild Road wasn’t just a suburban home; it was the physical anchor for a web of front companies, remote device hubs, and disguised income laundering pipelines that allowed DPRK IT workers to embed themselves inside U.S. companies.

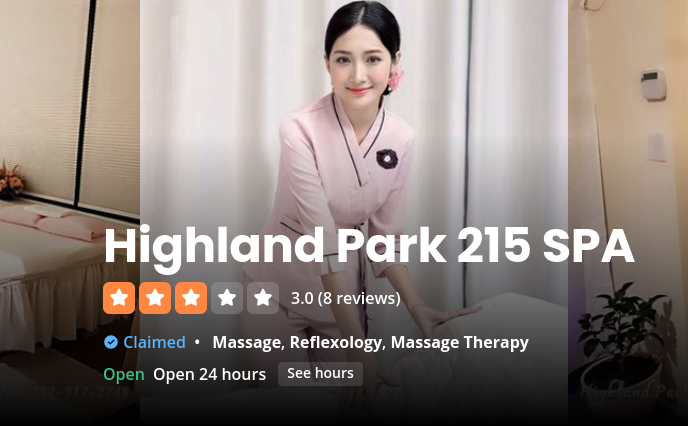

Wang operated under the radar, founding multiple businesses that appeared legitimate on paper but functioned primarily as pass-through entities for laundering salaries earned under false identities. These businesses included tech fronts, aviation firms, and even a massage parlor, each playing a role in the deception.

The most visible of these fronts was the Highland Park 215 Spa, located just a few miles from Wang’s listed residence. Officially a wellness spa, it appears to have functioned as a cash-out hub for crypto proceeds tied to North Korean developers. Its web presence was thin and reviews inconsistent, offering more red flags than relaxation.

Wang’s activities extended far beyond shell paperwork. He physically received laptops sent by U.S. companies hiring remote workers and connected them to internet-facing KVM switches. These switches allowed DPRK operatives, posing under names like “Joshua Palmer” or GitHub aliases like “devmad119”, to work as though they were based in the U.S. He also installed unauthorized software, managed credentials, and monitored access on behalf of the regime.

To keep the deception watertight, Wang opened corporate bank accounts, created digital presences for the fake companies, and maintained financial rails through platforms like Wise, Zelle, and Payoneer. His shell entities even issued IRS tax forms using stolen identity data, giving employers the impression that their freelance hires were tax-compliant U.S. residents.

Wang coordinated with a global network of co-conspirators, including Zhenxing Wang and Jing Bin Huang in China, Mengting Liu in Taiwan, and crypto brokers in the UAE and Russia. These connections formed the infrastructure that allowed funds from unsuspecting U.S. firms, including those in the defense sector, to end up in wallets controlled by the North Korean regime.

Court filings in DOJ case 25-cr-10274 paint a damning picture: Kejia Wang was not only aware that the workers were North Korean nationals, but also actively facilitated the laundering of more than $5 million in wages tied to fraud, of which at least $3 million resulted in direct corporate losses.

From his role as a logistics manager to a shell company architect, Wang helped build a shadow economy inside the legitimate global tech labor force, an economy designed to fund weapons development, evade sanctions, and penetrate sensitive digital infrastructure with ease.

Laptop Farms and Stolen Identities: Christina Chapman

Laptop farms function as remote access deception hubs, allowing foreign operatives to convincingly impersonate U.S.based employees. In this scheme, the perpetrators acquire and configure laptops sent by U.S. companies to individuals they believe are legitimate remote hires. These devices are logged into and maintained from U.S. soil, typically through physical setups in homes or small offices, so that all network traffic and telemetry appear domestic. The key to this illusion is identity theft. Recently, the DOJ indicted Christina Chapman, a facilitator in Arizona, who ran “Laptop Farms”. Once the hiring process was complete, victim companies would ship work laptops and grant access to sensitive systems, unaware that the real end users were North Korean nationals abroad. Chapman’s role was not only to receive and activate these laptops but to maintain them for continuous remote access, ensuring that DPRK operatives could stay invisible behind American identities.

Platform Penetration & Global Expansion

As enforcement tightened on global freelancing hubs such as Upwork, Fiverr, and Freelancer.com, North Korean IT operatives expanded their focus to less-regulated, regionally focused gig platforms, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). While major global platforms like Upwork and Freelancer still see DPRK IT worker recruitment, intelligence gathered throughout 2024 and 2025 indicates a broader strategy to infiltrate various online platforms. These platforms became attractive to DPRK-aligned actors due to their comparatively lenient onboarding processes, minimal identity verification, and weak vetting practices, which allow the actors to bypass employment verification controls.

This expansion coincided with observed DPRK tactics documented by Microsoft Threat Intelligence and Google Cloud’s Mandiant division , which reported the use of KVM switch setups , stolen identity kits , and remote desktop software to simulate domestic employment in a given jurisdiction—even when the worker operated from DPRK or China. Newer tactics include the use of synthetic voices for video interviews , AI-generated profile images , and automated deployment of identity documents that pass lightweight vetting procedures common to less-regulated platforms.

Payment pipelines also evolved. Payments are often facilitated through virtual currency, as well as services like TransferWise and Payoneer, implying a preference for systems with limited oversight. In 2025, DPRK operatives received payment through disbursement services into crypto wallets or offshore accounts, routing earnings through UAE-based infrastructure. However, the provided research does not directly corroborate specific incidents such as a “Ureed-based hire posing as a Syrian frontend engineer working for a UAE fintech company” or mobile application code delivered via “Nabbesh” by a user claiming to be Palestinian with telemetry traced to Vladivostok, Russia. However, the use of telemetry to detect Russian-linked infrastructure associated with DPRK activity is confirmed.

This redirection to under-monitored platforms reflects the regime’s operational flexibility. Instead of abandoning freelance infiltration altogether, Pyongyang expanded its reach into low-friction digital labor markets with lower regulatory visibility. This expansion not only preserved a steady stream of foreign currency for the regime , but it also increased DPRK’s reach into sectors and geographies beyond traditional U.S.-centric targets. It is not simply opportunistic—it is part of a deliberate, adaptive campaign of economic espionage masked as remote software development.

Shell Company Infrastructure

The DPRK IT labor operation was propped up by a web of shell companies that each played a distinct, carefully engineered role in laundering salaries, spoofing employment legitimacy, and obfuscating the true identities of North Korean operatives. At the core of this infrastructure was Kejia Wang, a New Jersey-based facilitator who established multiple legal entities across the U.S. to mask the flow of illicit wages. Hopana-Tech LLC served as a primary payroll conduit, accepting salary payments from victim companies under the guise of a legitimate staffing agency. Tony WKJ LLC was used to receive and deploy laptops to DPRK operatives, while also functioning as a salary masking layer. Independent Lab LLC provided the technical underpinnings, including blockchain API relays and crypto wallet infrastructure to route funds out of the U.S. financial system. Highland Park 215 Spa LLC, ostensibly operating under the cover of a massage parlor in New Jersey, likely acted as a cash-out point for laundering physical funds.

Wang also operated Northstar Leadership Inc., which produced fabricated resumes and managed identity paperwork, essential for onboarding DPRK operatives to hiring platforms. Through Capella Aviation LLC, Wang and co-registrant Liwen Huang routed wire transfers through Hong Kong and mainland China, creating a cross-border financial bridge. On the Russian front, Gayk Asatryan used Asatryan LLC and Fortuna LLC to legally host 80 DPRK workers, legitimizing their presence under 10-year employment contracts signed with North Korean trading firms.

These entities were not isolated -they were interconnected through shared addresses such as 65 Idlewild Road, overlapping registration details, and reused bank accounts and crypto wallets. Together, they formed a sophisticated scaffolding that gave the illusion of legitimate employment and enterprise, while operating as the foundation for one of the most complex sanctions-evasion schemes tied to DPRK’s Reconnaissance General Bureau.

DPRK Currency Transfers Via Banking

Kejia Wang, operating from New Jersey, functioned as the financial cornerstone of the DPRK’s U.S.-based laundering scheme. Through front companies like Hopana Tech LLC, Tony WKJ LLC, and Independent Lab LLC, he established business and money transfer accounts used to receive salary payments from U.S. companies unwittingly employing North Korean IT workers under false identities.

At Hopana Tech, Wang opened a U.S. bank account that took in over $464,000 from victim firms between January 2022 and April 2024. These funds were rerouted to overseas co-conspirators such as Jing Bin Huang and a network of Chinese shell entities (e.g., Shenyang Xiwang, Deep Tech, Aolien) via Bank of China and Standard Chartered (HK).

Simultaneously, Tony WKJ LLC received more than $1.6 million through a U.S. money transfer service (MTS-2), which Wang distributed to accounts linked to Enchia Liu, Food Yard Trading (Dubai), and Shenyang Sun-Lotus Tech. He personally siphoned $218,000 into his own U.S. checking account and another $412,000 to his personal MTS account. Between 2022 and 2023, he also received $237,000 in salary deposits into that same personal account, then forwarded $208,000 across 43 transfers to co-conspirators Huang and Tong Yuze.

Wang further disguised laptop handling and device access fees as routine payments labeled “CA laptops” and “NY laptops,” totaling over $55,000 sent to two U.S.-based facilitators.

Lastly, using MTS-3, Wang falsely registered Tony WKJ as a “VC-backed software firm” and received $352,949 from victim companies. When flagged by MTS staff, Wang lied about a DPRK worker under the alias “Wandee C.,” claiming he was a subcontracted developer.

In total, these financial maneuvers moved millions through U.S. infrastructure to overseas nodes, enabling DPRK operatives to mask their identities and launder salaries under the guise of legitimate tech consulting.

Crypto Payment Flows & Wallet Infrastructure

The laundering of salaries earned by North Korean IT operatives followed a structured, multi-phase pipeline designed to minimize traceability and regulatory exposure. In Phase 1: Salary Receipt, payments from unsuspecting U.S. and international companies were sent either to front companies, such as Hopana-Tech LLC and Independent Lab LLC, or directly to wallet addresses listed on the operatives’ GitHub profiles. These companies believed they were paying legitimate U.S.-based contractors, unaware that the workers were remote operatives in North Korea using stolen or forged identities.

Phase 2: Obfuscation began as soon as payments arrived. Smart contracts were employed to automatically split the incoming funds across clusters of Ethereum or TRON wallets. This fragmentation technique, similar to those used in ransomware operations, obscured the origin of the funds and made tracking the complete financial trail more difficult. Each tranche was redirected through different wallets, reducing the ability of investigators to correlate input/output flows with a single identity or origin point.

In Phase 3: Conversion, the obfuscated crypto was aggregated and funneled through over-the-counter (OTC) brokers based in Russia, the United Arab Emirates, and Hong Kong. These brokers specialize in converting large sums of stablecoins into fiat or alternative cryptocurrencies while avoiding compliance triggers. Eventually, the cleaned funds were consolidated into wallets under DPRK control, some of which have since been blocklisted by platforms like Tether for links to illicit activity and sanctions violations. This seamless pipeline allowed the DPRK to convert stolen or fraudulently earned wages into usable capital for the regime’s strategic programs, including its weapons development efforts.

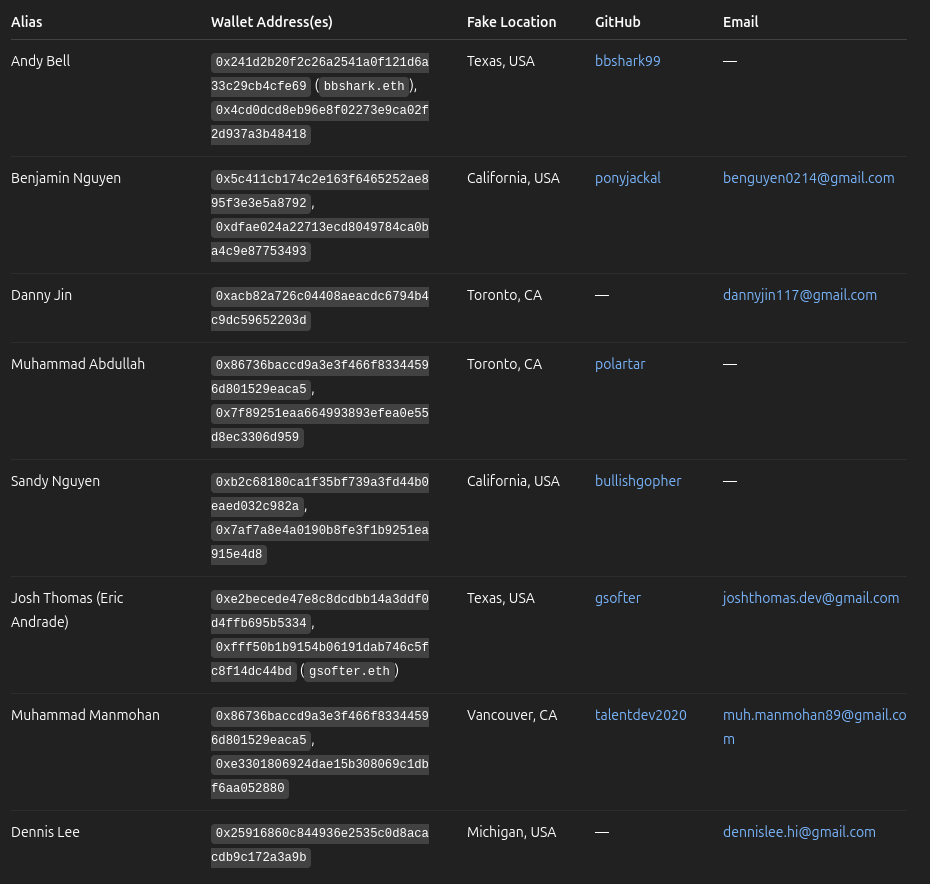

DPRK IT Worker Cluster Wallet & Identity Mapping

Eight fake identities represent a sophisticated and evolving strategy by the DPRK’s IT worker apparatus to not only infiltrate the U.S. based companies but to systematically exfiltrate salary payments into laundering pipelines that support North Korea’s sanctioned economy. Each alias, crafted with care and strategic foresight, was tied to a complex infrastructure of forged documents, crypto wallets, and online developer personas, all designed to evade detection by employers, banks, and regulators.

These aliases were not random. Many were modeled on plausible names common in the U.S., Canada, or Southeast Asia, making them more likely to pass identity verification or “soft KYC” checks on freelancing platforms and internal HR systems. They were often accompanied by polished Linkedin profiles, active GitHub repositories, and consistent communication habits, all of which contributed to the illusion of a legitimate remote developer.

Behind the scenes, each identity was directly linked to salary laundering flows. For instance, Andy Bell, Benjamin Nguyen, and Sandy Nguyen used ETH-based wallet addresses, including vanity ENS domains like bbshark[.]eth and gsofter[.]eth, to receive payments from U.S. firms under the guise of contract work. These addresses were often listed on their GitHub accounts as “payment preferred to…” links, allowing unsuspecting employers or payroll processors to initiate transfers.

In many cases, funds were first routed to these GitHub-linked wallets, then automatically or manually split using smart contracts across secondary addresses. From there, the payments were funneled to consolidation wallets controlled by DPRK facilitators or OTC brokers in Russia, China, or the UAE. For example, funds from wallets tied to Josh Thomas and Muhammad Abdullah were traced via ZachXBT and TRM Labs to known laundering hubs tied to sanctioned North Korean operators. (*ZachXBT is a self-taught, pseudonymous blockchain investigator who has gained global recognition for tracking fraudulent crypto transactions, hacks, rug pulls, and state-linked laundering schemes.)

The fake geographic locations assigned to these aliases were deliberately chosen to align with employment demand and reduce suspicion, such as Texas, California, Toronto, and Michigan, regions known for tech industry presence. These locations also matched VPN exit nodes and remote access IP ranges used to simulate U.S.-based developer activity during work hours.

In total, these eight identities were tied to at least 12 different U.S. and international projects. They helped siphon hundreds of thousands in salaries, while embedding DPRK-linked code contributors into the core of web3 startups, fintech platforms, and even infrastructure projects. Their exposure now offers critical insight into the DPRK’s strategy: weaponizing remote work, exploiting global labor gaps, and turning open-source ecosystems into vectors of economic subversion.

Associated Consolidation Wallets

ZachXBT reports that all above identities and payment addresses lead to two known consolidation wallets:

These wallets serve as hubs in laundering pathways, taking in payments from U.S. firms and redistributing to DPRK-controlled endpoints via OTC brokers and blacklisted channels. These are frequently referenced in TRM Labs and Treasury forfeiture filings.

Global Network of Enablers

The DPRK’s IT worker laundering network was supported by a multinational cast of facilitators operating across five regions, each providing critical functions that enabled the scheme to scale globally. In the United States, Kejia Wang and Zhenxing “Danny” Wang served as the domestic linchpins, establishing shell companies like Hopana-Tech LLC and Independent Lab LLC, receiving company-issued laptops, and enabling remote access for DPRK operatives via KVM switches. In China, actors such as Jing Bin Huang, Tong Yuze, and Zhenbang Zhou were responsible for setting up domain infrastructure, fabricating identity records, and acting as intermediaries in the salary flow chain. Operating from the United Arab Emirates, Yongzhe Xu and Ziyou Yuan handled the setup of financial accounts and cryptocurrency wallets that served as routing points for laundered funds. Meanwhile, in Taiwan, Mengting Liu and Enchia Liu were tasked with salary account management and crypto-to-cash withdrawal, helping to finalize the money laundering cycle. In Russia, Gayk Asatryan took on a more formal role, entering into 10-year labor agreements with DPRK trading entities and providing legal cover through his companies Asatryan LLC and Fortuna LLC for the long-term hosting of North Korean IT workers. Together, these individuals formed the logistical and financial scaffolding behind one of the DPRK’s most successful sanctions evasion operations to date.

Domains Used to Mask DPRK Labor Pipelines

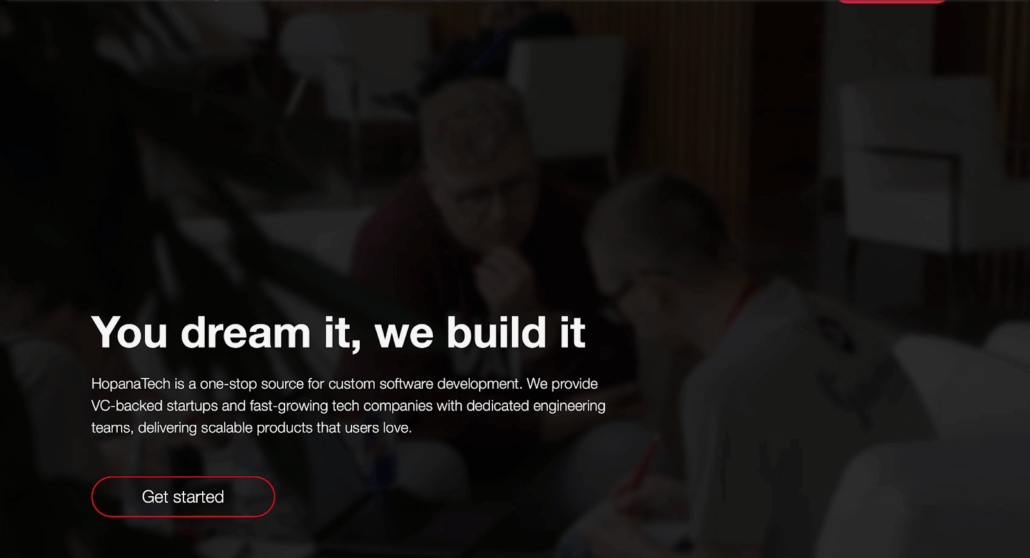

While the physical infrastructure of DPRK’s cyber-labor operation is anchored in shell companies and banking channels, its digital front is built on a deceptively simple architecture: domain registrations and simple, one-layer-deep web sites. Four key domains, hopanatech[.]com, tonywangtech.com, wkjllc[.]com, and inditechlab[.]com, emerged as critical components of the laundering and deception ecosystem.

All four were registered through NameCheap, a domain registrar frequently exploited by threat actors for its lenient Know-Your-Customer (KYC) policies. These domains aligned closely with the shell companies documented in the July 2025 indictment of Kejia Wang (aka Tony Wang).

- hopanatech[.]com: Used as a façade for the employer-of-record shell “Hopana Tech LLC.” This site served as a point of contact and “employment verification” front, meant to convince firms that IT workers were U.S.-based.

- tonywangtech[.]com and wkjllc.com: Variations on the Tony WKJ LLC shell, these domains were used to generate email aliases and submit resumes under false identities. They helped DPRK contractors pass due diligence by appearing affiliated with a legitimate tech firm.

- inditechlab[.]com: Tied to Independent Lab LLC, a shell involved in crypto infrastructure. The domain may have also hosted webhooks and API interfaces used in TRON-based laundering flows.

Despite their differing branding, these domains shared clear indicators of clustering:

- Similar registrar info and name servers

- Absence of advanced metadata like Google Analytics or embedded tracking (indicating high OPSEC awareness)

- WHOIS privacy enabled

- Associated email accounts and DNS infrastructure linked to Wang or his co-conspirators

These domains were not just placeholders. They were operationally active, used in job applications, HR communications, resume verification, and even crypto billing. In short, they functioned as front-facing digital camouflage for a covert state-aligned economic espionage program.

Strategic and Financial Impact

By the first half of 2025, North Korea’s covert IT labor scheme had evolved into a robust revenue-generating apparatus capable of siphoning millions from the global economy with alarming precision. An estimated $17 million in salary payments was funneled through shell companies and direct crypto wallets tied to DPRK operatives posing as freelance developers. It is also cited that the total for the scheme globally netted between $250 to $600 million altogether. These payments came from hundreds of U.S. companies, including fintech startups, SaaS vendors, blockchain firms, and even defense contractors, who unknowingly onboarded North Korean nationals through falsified resumes and forged identity documents. In June 2025, U.S. authorities seized $7.7 million in cryptocurrency assets connected to the scheme, targeting wallets tied to aliases like “devmad119” and “Joshua Palmer.” Yet this represents just a fraction of the broader threat: over $1.6 billion in global cryptocurrency losses were attributed to DPRK-linked actors in the same time period, with 70% directly traced to operations blending employment fraud, social engineering, and codebase compromise. Far beyond financial theft, this scheme granted North Korean operatives persistent system access, enabling the injection of malicious logic, exfiltration of proprietary code, and creation of long-term backdoors across critical sectors.

Insider Threats: Espionage by Employment

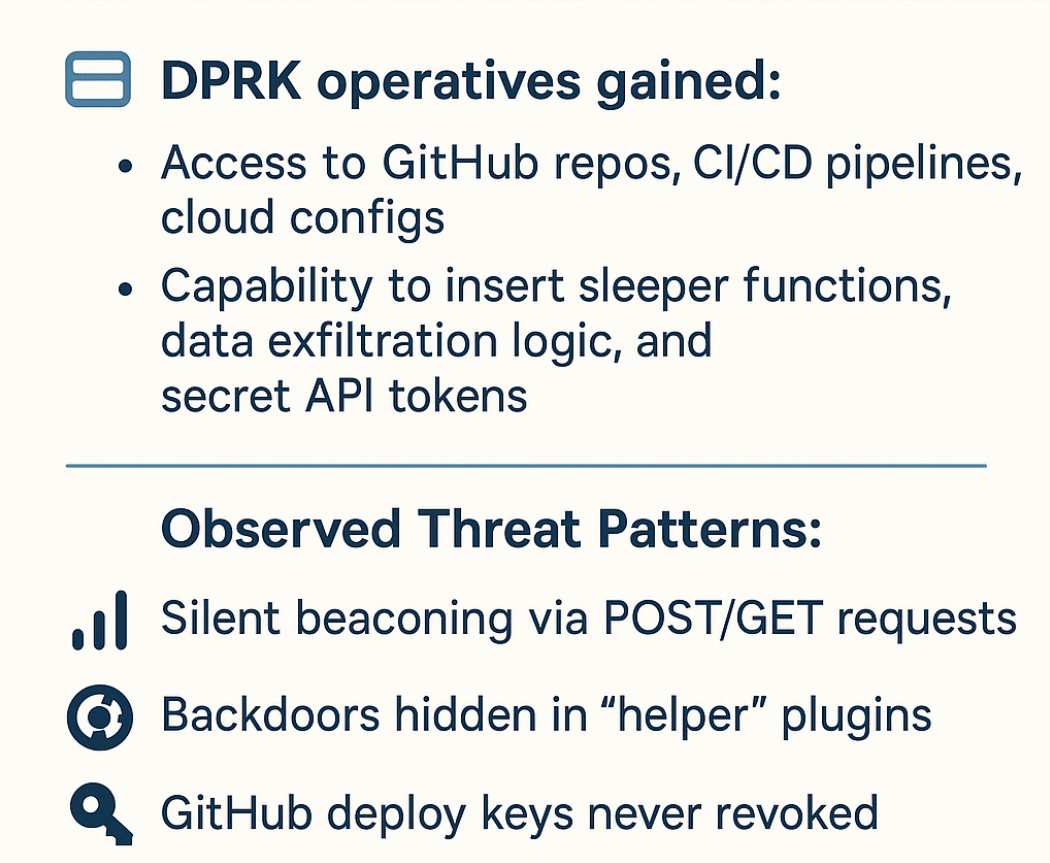

North Korean IT operatives, posing as legitimate remote developers, evolved from mere economic infiltrators to full-fledged insider threats. Once embedded within U.S. and foreign tech firms, these operatives obtained privileged access to critical assets, including GitHub repositories, CI/CD pipelines (like Jenkins and GitLab), and cloud configuration files across AWS, Azure, and GCP. With this level of access, they would be able to insert stealthy “sleeper” functions, delayed or dormant code designed to activate later, as well as data exfiltration logic disguised within standard requests, such as base64-encoded POST or GET calls.

To date, no official disclosures from the government or private sector have confirmed that such actions have occurred. However, given that these nation-state adversaries were embedded as insider threats, it is reasonable to assess that once they gained access to sensitive networks and digital assets, they likely exploited opportunities that extended beyond financial fraud. The potential for strategic espionage, leveraging their privileged access for intelligence collection or cyber sabotage, must be considered a probable scenario.

Threat Assessment

The infiltration of DPRK IT workers into Western firms represents one of the most sophisticated and insidious insider threat campaigns in recent memory. Unlike external cyberattacks that can be blocked at the perimeter, these operatives gained trusted persistent access inside corporate networks by posing as vetted remote employees. Once hired, often via stolen, background-verified U.S. identities, they were embedded into critical roles such as backend development, cloud configuration, CI/CD pipeline maintenance, and DevOps infrastructure. This level of access granted them entry into source code repositories, production environments, encryption logic, and proprietary APIs, allowing for potential IP theft, backdoor insertion, credential harvesting, and pre-positioning for future attacks.

This threat was magnified by a widespread failure among companies to implement robust asset management, access logging, and behavioral anomaly detection. In many cases, organizations lacked visibility into who exactly was accessing which systems, when, and from where. The use of remote KVM switches, proxy VPNs, and U.S.-based cloud endpoints enabled DPRK operatives to blend in with legitimate employee traffic, bypassing geo-fencing or basic endpoint monitoring. Some firms failed to enforce multi-factor authentication, revoke GitHub deploy keys upon contractor termination, or monitor suspicious API activity from “internal” users. Additionally, lax onboarding processes and over-reliance on third-party background check platforms meant many identities went unverified or unchecked.

To counter these threats, companies must enforce zero-trust security models, where access is continuously evaluated based on device health, location, and behavioral norms. Automated asset inventories, real-time session monitoring, and privileged access management (PAM) should be standard practice. Every contractor should have narrowly scoped, time-limited access tied to individual credentials, with full audit trails and immediate revocation mechanisms. Organizations must also reevaluate how they vet remote talent, introducing biometric verification, live interviews, and cross-checks with employment databases to prevent identity fraud. Failure to do so risks granting hostile nation-state actors like the DPRK the keys to their most valuable digital assets, without ever breaching a firewall.

Conclusion

The breaking up of the DPRK IT workers exploit is a wake up call for corporations around the world. The aphorism of “The insider threat is the biggest threat” in the infosec space rings true here with a clarion call. So far, the information that has come out (and continues to be researched) seems to indicate that the U.S. was not the only target of the DPRK activities. That said, it is important that corporations and organizations understand the aphorism above, and do all they can to ensure such insider attacks are much harder to carry out.

It is also important that, within the new paradigm of AI, interviews, vetting, and generally, everything carried out during the interview and vetting process, be backstopped to ensure authentic individuals are being hired, and not assets of a foreign power, or for that matter, other criminal actors. This new landscape will only get more complex, and as we move forward into this brave new world, expect there to be other exploits like these that could render your operations into extreme response circumstances.

Sign Up For DomainTools Investigations’ Newsletter for the Latest Research

Want more from DomainTools Investigations? Be sure to sign up for our monthly newsletter to get the latest research from the team – available on LinkedIn or email.

Related Content

APT35/Charming Kitten's leaked documents expose the financial machinery behind state-sponsored hacking. Learn how bureaucracy, crypto micro-payments, and administrative ledgers sustain Iranian cyber operations and link them to Moses Staff.